Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

30 May 2024

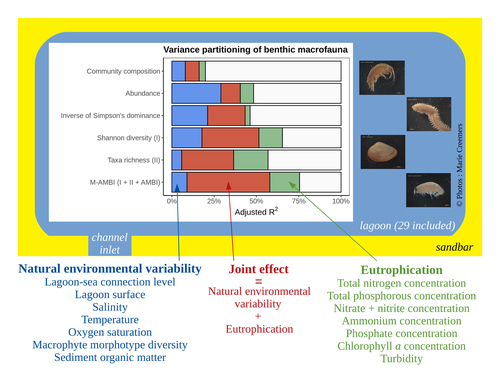

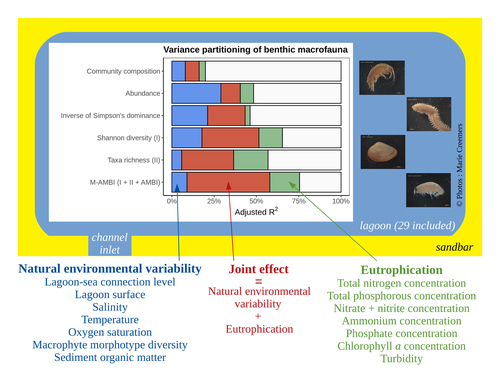

Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoonsAuriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.18.504439Untangling Eutrophication Effects on Coastal Lagoon EcosystemsRecommended by Nathalie Niquil based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright

Disentangling the effects on ecosystem structure and functioning of natural and human-induced impacts in transitional waters is a great challenge in coast ecology. This is due to the observation that the ecosystems of transitional waters are naturally dynamic systems with characteristics of stressed systems. For example, the benthic communities present low species richness and high abundance of species with a high tolerance to variations, e.g., salinity. This general observation is known as the paradigm of the “Transitional Waters Quality Paradox” (Zaldívar et al., 2008) derived from the previously described “Estuarine Quality Paradox” (Elliott and Quintino, 2007). In Jones et al. (2024) “Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons”, a great diversity of lagoons is analyzed to disentangle the effects of eutrophication from those of natural environmental variability on benthic macroinvertebrates and understanding the links between environmental variables affecting benthic macroinvertebrates. These authors use a very elegant set of numerical approaches, including correlograms, linear models and variance partitioning. They apply this suite to a dataset of macrobenthic invertebrate abundances and environmental variables from 29 Mediterranean coastal lagoons in France. Through this suite of analyses, they demonstrate the strong complexity of the mechanisms interplaying in a situation of eutrophication on lagoon macrobenthos. The mechanisms involved are direct, like toxicity, or indirect, for example, through modifications of the sediment's biogeochemistry. Such a result on the different interactions involved is very important in the context of the search for indicators to define ecosystem status. Improving the definition of metrics is essential in environmental management decisions. References Elliott, M. and Quintino, V. (2007) The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.02.003 Zaldívar, J. (2008). Eutrophication in transitional waters: an overview. https://doi.org/10.1285/I18252273V2N1P1 | Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons | Auriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are transitional ecosystems that host a unique diversity of species and support many ecosystem services. Owing to their position at the interface between land and sea, they are also subject to increa... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Marine ecology | Nathalie Niquil | Matthew J. Pruden | 2023-09-08 11:26:01 | View |

24 May 2024

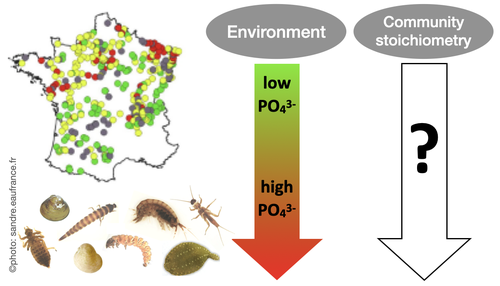

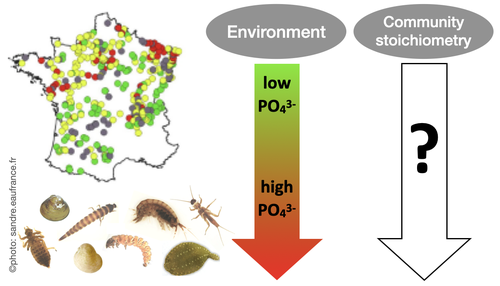

Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale studyMiriam Beck, Elise Billoir, Philippe Usseglio-Polatera, Albin Meyer, Edwige Gautreau, Michael Danger https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.01.574823The influence of water phosphorus and nitrogen loads on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometryRecommended by Huihuang Chen based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo and 1 anonymous reviewer

The manuscript by Beck et al. (2024) investigates the effects of water phosphorus and nitrogen loads on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry across France. Utilizing data from over 1300 standardized sampling events, this research finds that community stoichiometry is significantly influenced by water phosphorus concentration, with the strongest effects at low nitrogen levels. The results demonstrate that the assumptions of Ecological Stoichiometry Theory apply at the community level for at least two dominant taxa and across a broad spatial scale, with probable implications for nutrient cycling and ecosystem functionality. This manuscript contributes to ecological theory, particularly by extending Ecological Stoichiometry Theory to include community-level interactions, clarifying the impact of nutrient concentrations on community structure and function, and informing nutrient management and conservation strategies. In summary, this study not only addresses a gap in community-level stoichiometric research but also delivers crucial empirical support for advancing ecological science and promoting environmental stewardship. References Beck M, Billoir E, Usseglio-Polatera P, Meyer A, Gautreau E and Danger M (2024) Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale study. bioRxiv, 2024.02.01.574823, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.01.574823 | Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale study | Miriam Beck, Elise Billoir, Philippe Usseglio-Polatera, Albin Meyer, Edwige Gautreau, Michael Danger | <p>Basal resources generally mirror environmental nutrient concentrations in the elemental composition of their tissue, meaning that nutrient alterations can directly reach consumer level. An increased nutrient content (e.g. phosphorus) in primary... |  | Community ecology, Ecological stoichiometry | Huihuang Chen | Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo, Anonymous | 2024-02-02 10:14:01 | View |

13 May 2024

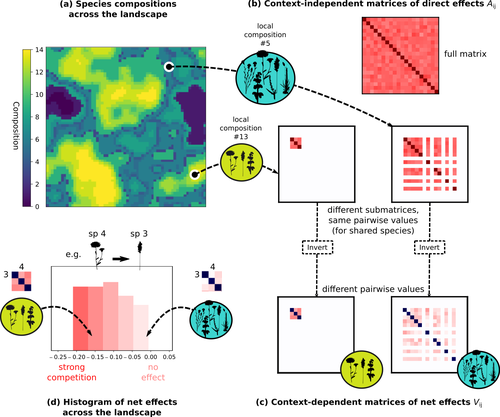

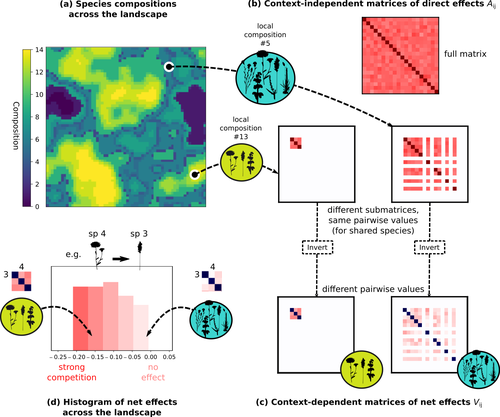

Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in MetacommunitiesMatthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.04.543606Beyond pairwise species interactions: coarser inference of their joined effects is more relevantRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler

Barbier et al. (2024) investigated the dynamics of species abundances depending on their ecological niche (abiotic component) and on (numerous) competitive interactions. In line with previous evidence and expectations (Barbier et al. 2018), the authors show that it is possible to robustly infer the mean and variance of interaction coefficients from species co-distributions, while it is not possible to infer the individual coefficient values. The authors devised a simulation framework representing multispecies dynamics in an heterogeneous environmental context (2D grid landscape). They used a Lotka-Volterra framework involving pairwise interaction coefficients and species-specific carrying capacities. These capacities depend on how well the species niche matches the local environmental conditions, through a Gaussian function of the distance of the species niche centers to the local environmental values. They considered two contrasted scenarios denoted as « Environmental tracking » and « Dispersal limited ». In the latter case, species are initially seeded over the environmental grid and cannot disperse to other cells, while in the former case they can disperse and possibly be more performant in other cells. The direct effects of species on one another are encoded in an interaction matrix A, and the authors further considered net interactions depending on the inverse of the matrix of direct interactions (Zelnik et al., 2024). The net effects are context-dependent, i.e., it involves the environment-dependent biotic capacities, even through the interaction terms can be defined between species as independent from local environment. The results presented here underline that the outcome of many individual competitive interactions can only be understood in terms of macroscopic properties. In essence, the results here echoe the mean field theories that investigate the dynamics of average ecological properties instead of the microscopic components (e.g., McKane et al. 2000). In a philosophical perspective, community ecology has long struggled with analyzing and inferring local determinants of species coexistence from species co-occurrence patterns, so that it was claimed that no universal laws can be derived in the discipline (Lawton 1999). Using different and complementary methods and perspectives, recent research has also shown that species assembly parameter values cannot be unambiguously inferred from species co-occurrences only, even in simple designs where an equilibrium can be reached (Poggiato et al. 2021). Although the roles of high-order competitive interactions and intransivity can lead to species coexistence, the simple view of a single loop of competitive interactions is easily challenged when further interactions and complexity is added (Gallien et al. 2024). But should we put so much emphasis on inferring individual interaction coefficients? In a quest to understand the emerging properties of elementary processes, ecological theory could go forward with a more macroscopic analysis and understanding of species coexistence in many communities. The authors referred several times to an interesting paper from Schaffer (1981), entitled « Ecological abstraction: the consequences of reduced dimensionality in ecological models ». It proposes that estimating individual species competition coefficients is not possible, but that competition can be assessed at the coarser level of organisation, i.e., between ecological guilds. This idea implies that the dimensionality of the competition equations should be greatly reduced to become tractable in practice. Taking together this claim with the results of the present Barbier et al. (2024) paper, it becomes clearer that the nature of competitive interactions can be addressed through « abstracted » quantities, as those of guilds or the moments of the individual competition coefficients (here the average and the standard deviation). Therefore the scope of Barbier et al. (2024) framework goes beyond statistical issues in parameter inference, but question the way we must think and represent the numerous competitive interactions in a simplified and robust way. References Barbier, Matthieu, Jean-François Arnoldi, Guy Bunin, et Michel Loreau. 2018. « Generic assembly patterns in complex ecological communities ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9): 2156‑61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710352115 | Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in Metacommunities | Matthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold | <p>AbstractOne of the more difficult challenges in community ecology is inferring species interactions on the basis of patterns in the spatial distribution of organisms. At its core, the problem is that distributional patterns reflect the ‘realize... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Competition, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2023-10-21 14:14:16 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

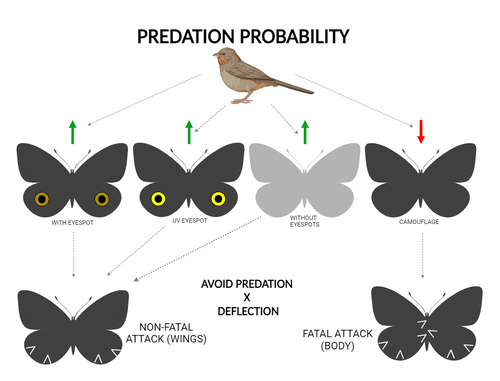

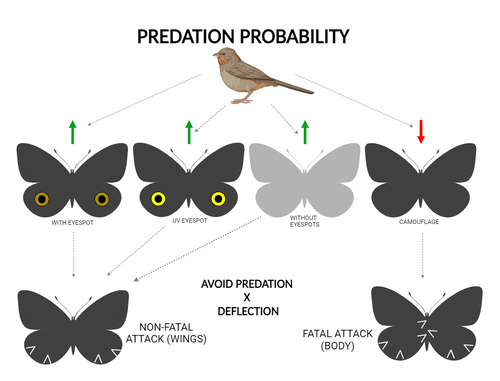

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View | |

19 Mar 2024

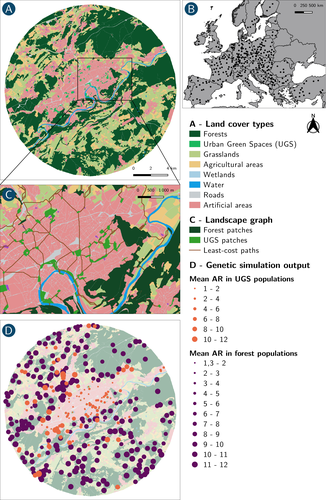

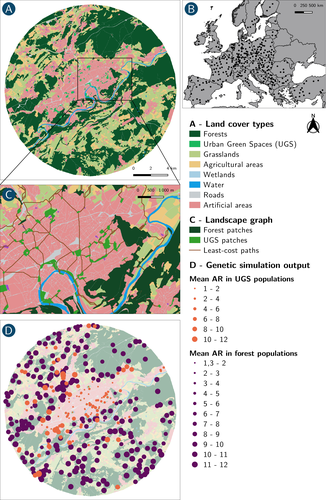

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View | |

11 Mar 2024

Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammalAmin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920Stress and stress hormones’ transmission from mothers to offspringRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Individuals can respond to environmental changes that they undergo directly (within-generation plasticity) but also through transgenerational plasticity, providing lasting effects that are transmitted to the next generations (Donelson et al. 2012; Munday et al. 2013; Kuijper & Hoyle 2015; Auge et al. 2017, Tariel et al. 2020). These parental effects can affect offspring via various mechanisms, notably via maternal transmission of hormones to the eggs or growing embryos (Mousseau & Fox 1998). While the effects of environmental quality may simply carry-over to the next generation (e.g., females in stressful environments give birth to offspring in poorer condition), parental effects may also be a mechanism that adjusts offspring phenotype in response to environmental variation and predictability, and thereby match offspring's phenotype to future environmental conditions (Gluckman et al. 2005; Marshall & Uller 2007; Dey et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2019), for example by preparing their offspring to an expected stressful environment. When females experience stress during gestation or egg formation, elevations in glucocorticoids (GC) are expected to affect offspring phenotype in many ways, from the offspring's own GC levels, to their growth and survival (Sheriff et al. 2017). This is a well established idea, but how strong is the evidence for this? A meta-analysis on birds found no clear effect of corticosterone manipulation on offspring traits (38 studies on 9 bird species for corticosterone manipulation; Podmokła et al. 2018). Another meta-analysis including 14 vertebrate species found no clear effect of prenatal stress on offspring GC (Thayer et al. 2018). Finally, a meta-analysis on wild vertebrates (23 species) found no clear effect of GC-mediated maternal effects on offspring traits (MacLeod et al. 2021). As often when facing such inconclusive results, context dependence has been suggested as one potential reason for such inconsistencies, for exemple sex specific effects (Groothuis et al. 2019, 2020). However, sex specific measures on offspring are scarce (Podmokła et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature available is still limited to a few, mostly “model” species. With their study, Amin et al. (2024) show the way to improve our understanding on GC transmission from mother to offspring and its effects in several aspects. First they used innovative non-invasive methods (which could broaden the range of species available to study) by quantifying cortisol metabolites from faecal samples collected from pregnant females, as proxy for maternal GC level, and relating it to GC levels from hairs of their neonate offspring. Second they used a free ranging large mammal (taxa from which literature is missing): the fallow deer (Dama dama). Third, they provide sex specific measures of GC levels. And finally but importantly, they are exemplary in their transparency regarding 1) the exploratory nature of their study, 2) their statistical thinking and procedure, and 3) the study limitations (e.g., low sample size and high within individual variation of measurements). I hope this study will motivate more research (on the fallow deer, and on other species) to broaden and strengthen our understanding of sex specific effects of maternal stress and CG levels on offspring phenotype and fitness. References Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., & Ciuti, S. (2024). Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and foetal glucocorticoids in a free-ranging large mammal. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920 Auge, G.A., Leverett, L.D., Edwards, B.R. & Donohue, K. (2017). Adjusting phenotypes via within-and across-generational plasticity. New Phytologist, 216, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14495 Dey, S., Proulx, S.R. & Teotonio, H. (2016). Adaptation to temporally fluctuating environments by the evolution of maternal effects. PLoS biology, 14, e1002388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002388 Donelson, J.M., Munday, P.L., McCormick, M.I. & Pitcher, C.R. (2012). Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1323 Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A. & Spencer, H.G. (2005). Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001 Groothuis, Ton GG, Bin-Yan Hsu, Neeraj Kumar, and Barbara Tschirren. "Revisiting mechanisms and functions of prenatal hormone-mediated maternal effects using avian species as a model." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374, no. 1770 (2019): 20180115. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0115 Groothuis, Ton GG, Neeraj Kumar, and Bin-Yan Hsu. "Explaining discrepancies in the study of maternal effects: the role of context and embryo." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36 (2020): 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.10.006 Kuijper, B. & Hoyle, R.B. (2015). When to rely on maternal effects and when on phenotypic plasticity? Evolution, 69, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12635 MacLeod, Kirsty J., Geoffrey M. While, and Tobias Uller. "Viviparous mothers impose stronger glucocorticoid‐mediated maternal stress effects on their offspring than oviparous mothers." Ecology and Evolution 11, no. 23 (2021): 17238-17259. Marshall, D.J. & Uller, T. (2007). When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos, 116, 1957–1963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x Mousseau, T.A. & Fox, C.W. (1998). Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press. Munday, P.L., Warner, R.R., Monro, K., Pandolfi, J.M. & Marshall, D.J. (2013). Predicting evolutionary responses to climate change in the sea. Ecology Letters, 16, 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12185 Podmokła, Edyta, Szymon M. Drobniak, and Joanna Rutkowska. "Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method–a meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 93, no. 3 (2018): 1499-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12406 Sheriff, M. J., Bell, A., Boonstra, R., Dantzer, B., Lavergne, S. G., McGhee, K. E., MacLeod, K. J., Winandy, L., Zimmer, C., & Love, O. P. (2017). Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105 Tariel, Juliette, Sandrine Plénet, and Émilien Luquet. "Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (2020): 548660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.548660 Thayer, Zaneta M., Meredith A. Wilson, Andrew W. Kim, and Adrian V. Jaeggi. "Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: A phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species." Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 4942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23169-w Yin, J., Zhou, M., Lin, Z., Li, Q.Q. & Zhang, Y.-Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects benefit offspring across diverse environments: a meta-analysis in plants and animals. Ecology letters, 22, 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13373 | Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammal | Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Maternal phenotypes can have long-term effects on offspring phenotypes. These maternal effects may begin during gestation, when maternal glucocorticoid (GC) levels may affect foetal GC levels, thereby having an orga... | Evolutionary ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Physiology, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-06-05 09:06:56 | View | ||

01 Mar 2024

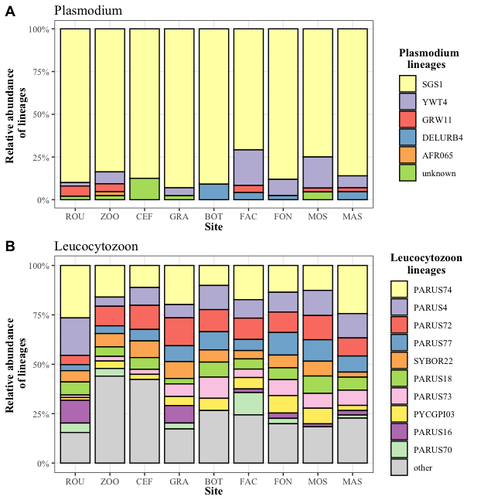

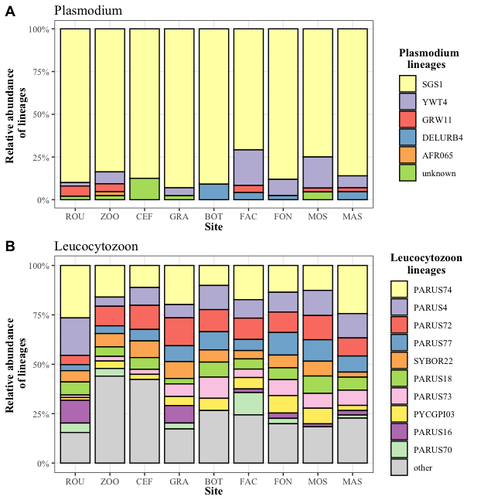

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

20 Feb 2024

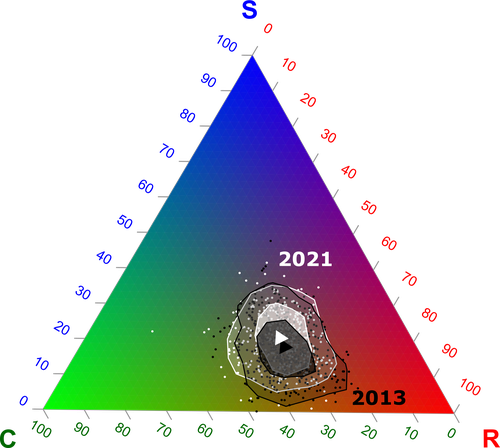

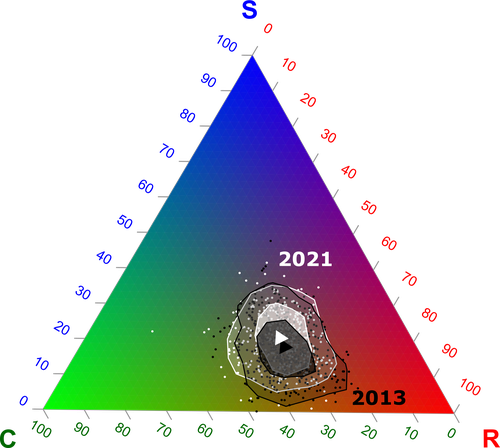

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practicesIsis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persistRecommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clélia Sirami and Diego Gurvich based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clélia Sirami and Diego Gurvich

Agricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ. References Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013 Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2 Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005 Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244 Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14 Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain. Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003 Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956 Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715 | Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices | Isis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried | <p style="text-align: justify;">Over the past decades, agricultural intensification and climate change have led to vegetation shifts. However, functional trade-offs linking traits responding to climate and farming practices are rarely analyzed, es... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Climate change, Community ecology | Julia Astegiano | 2023-03-04 15:40:35 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Vasilis Dakos (Representative)

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle