WALCZYŃSKA Aleksandra

- Institute of Environmental Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland

- Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Habitat selection, Life history, Thermal ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 3

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 3

Crop productivity of Central European Permaculture is within the range of organic and conventional agriculture.

Permaculture, a promising alternative to conventional agriculture

Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Paulina Kramarz, Leda Lorenzo Montero and 1 anonymous reviewerAs mankind develops increasingly efficient and productive methods of agriculture and food production, we have reached a point where intensive agriculture threatens several aspects of life on Earth, negatively affecting biodiversity, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles and water reservoirs, while producing considerable amounts of greenhouse gases (Krebs and Bach, 2018). There was a need to develop farming methods that were friendly to both nature and people, producing good quality, healthy food without destroying the environment. The idea of permaculture, a concept of sustainable agriculture based on methods learned directly from nature, originated in the 1960s, invented and developed by Bruce Charles Mollison and David Holmgren (Mollison and Holmgren 1979, Mollison et al. 1991, Holmgren 2002). Although the idea of permaculture has attracted scientific interest, the representation in published studies is unbalanced in favour of positive ecological and sociological effects, with much less presence of rigorous experimental testing (Ferguson and Lovell 2014, Reiff et al. 2024a).

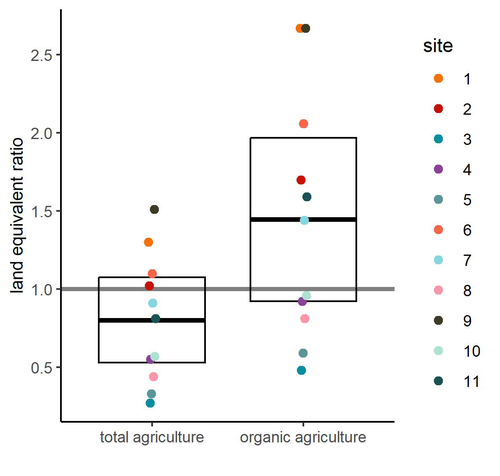

Reiff et al. (2024b) provided the first large-scale empirical evidence of permaculture production outcomes for Central Europe. Based on results from 11 commercial permaculture sites, situated mostly in Germany but also in Switzerland and Luxembourg, the authors found that food production from permaculture sites was on average comparable to that from conventional and organic agriculture. The authors were very thorough in pointing out the issues that could potentially affect their results and which need further testing.

Among these, the authors highlight the considerable variability between the 11 sites studied, which may suggest that different permacultures should differ in details according to their specificity - an interesting issue that definitely requires further study. The other factor that the authors point out that could have influenced the results and led to an underestimation of the real potential is the age of the permaculture sites. The sites from the study were relatively young, and their potential can be expected to increase with time.

It is important to note that the results are mostly applicable to vegetables, as vegetable production accounted for 94% of production in the permaculture sites (followed by tree crops, 6%, and soft fruit production, 0.5%). There is therefore a need to include other types of crops produced in further studies of this type.

To date, the results informing permaculture food production are urgently needed and should cover the potentially wide range of geographical regions and crops produced. The results of Reiff et al. (2025) show that rigorous testing of this issue is demanding, but the authors provide a very sound "road map" of further steps.

Literature:

Ferguson R. S. and Lovell S. T. 2014. Permaculture for agroecology: design, movement, practice, and worldview. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 34, 251-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6

Holmgren D. 2002. Permaculture: Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Holmgren Design Services, pp. 320.

Krebs J. and Bach S. 2018. Permaculture – scientific evidence of principles for the agroecological design of farming systems. Sustainability 10, 3218, https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093218

Mollison B. C. and Holmgren D. 1979. Permaculture One: A Perennial Agricultural System for Human Settlements. Tagari Publications, pp. 136.

Mollison B. C., Slay, R. M. and Jeeves A. 1991. Introduction to permaculture. Tagari Publications, pp. 198.

Reiff J., Jungkunst H. F., Mauser K. M., Kampel S., Regending S., Rösch V., Zaller J. G. and Entling M. H. 2024a. Permaculture enhances carbon stocks, soil quality and biodiversity in Central Europe. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01405-8

Reiff J., Jungkunst H. F., Antes N. and Entling M. H. 2024b. Crop productivity of Central European Permaculture is within the range of organic and conventional agriculture. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.09.611985

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern France

Why are trout getting smaller?

Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable.

This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea.

The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing.

These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019).

References

Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103

Barneche, D. R. et al. 2018. Fish reproductive-energy output increases disproportionately with body size. Science Vol 360, 642-645. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao6868

Josset, Q. et al. 2024. Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern France. biorXiv, 2023.11.21.568009, ver 4, Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009

Marshall, D. J. and White, C. R. 2019. Have we outgrown the existing models of growth? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34, 102-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.10.005

Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z

Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626

Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms

Effect of food conditions on the Temperature-Size Rule

Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Wilco VerberkTemperature-size rule (TSR) is a phenomenon of plastic changes in body size in response to temperature, originally observed in more than 80% of ectothermic organisms representing various groups (Atkinson 1994). In particular, ectotherms were observed to grow faster and reach smaller size at higher temperature and grow slower and achieve larger size at lower temperature. This response has fired the imagination of researchers since its invention, due to its counterintuitive pattern from an evolutionary perspective (Berrigan and Charnov 1994). The main question to be resolved is: why do organisms grow fast and achieve smaller sizes under more favourable conditions (= relatively higher temperature), while they grow longer and achieve larger sizes under less favourable conditions (relatively lower temperature), if larger size means higher fitness, while longer development may be risky?

This evolutionary conundrum still awaits an ultimate explanation (Angilletta Jr et al. 2004; Angilletta and Dunham 2003; Verberk et al. 2021). Although theoretical modelling has shown that such a growth pattern can be achieved as a response to temperature alone, with a specific combination of energetic parameters and external mortality (Kozłowski et al. 2004), it has been suggested that other temperature-dependent environmental variables may be the actual drivers of this pattern. One of the most frequently invoked variable is the relative oxygen availability in the environment (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2006; Audzijonyte et al. 2019; Verberk et al. 2021; Woods 1999), which decreases with temperature increase. Importantly, this effect is more pronounced in aquatic systems (Forster et al. 2012). However, other temperature-dependent parameters are also being examined in the context of their possible effect on TSR induction and strength.

Food availability is among the interfering factors in this regard. In aquatic systems, nutritional conditions are generally better at higher temperature, while a range of relatively mild thermal conditions is considered. However, there are no conclusive results so far on how nutritional conditions affect the plastic body size response to acute temperature changes. A study by Bazin et al. (2023) examined this particular issue, the effects of food and temperature on TSR, in medaka fish. An important value of the study was to relate the patterns found to fitness. This is a rare and highly desirable approach since evolutionary significance of any results cannot be reliably interpreted unless shown as expressed in light of fitness.

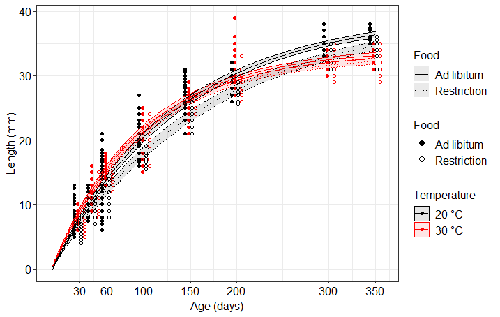

The authors compared the body size of fish kept at 20°C and 30°C under conditions of food abundance or food restriction. The results showed that the TSR (smaller body size at 30°C compared to 20°C) was observed in both food treatments, but the effect was delayed during fish development under food restriction. Regarding the relevance to fitness, increased temperature resulted in more eggs laid but higher mortality, while food restriction increased survival but decreased the number of eggs laid in both thermal treatments. Overall, food restriction seemed to have a more severe effect on development at 20°C than at 30°C, contrary to the authors’ expectations.

I found this result particularly interesting. One possible interpretation, also suggested by the authors, is that the relative oxygen availability, which was not controlled for in this study, could have affected this pattern. According to theoretical predictions confirmed in quite many empirical studies so far, oxygen restriction is more severe at higher temperatures. Perhaps for these particular two thermal treatments and in the case of the particular species studied, this restriction was more severe for organismal performance than the food restriction. This result is an example that all three variables, temperature, food and oxygen, should be taken into account in future studies if the interrelationship between them is to be understood in the context of TSR. It also shows that the reasons for growing smaller in warm may be different from those for growing larger in cold, as suggested, directly or indirectly, in some previous studies (Hessen et al. 2010; Leiva et al. 2019).

Since medaka fish represent predatory vertebrates, the results of the study contribute to the issue of global warming effect on food webs, as the authors rightly point out. This is an important issue because the general decrease in the size or organisms in the aquatic environment with global warming is a fact (e.g., Daufresne et al. 2009), while the question of how this might affect entire communities is not trivial to resolve (Ohlberger 2013).

REFERENCES

Angilletta Jr, M. J., T. D. Steury & M. W. Sears, 2004. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life–history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44:498-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498

Angilletta, M. J. & A. E. Dunham, 2003. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: Simple evolutionary explanations may not be general. American Naturalist 162(3):332-342. https://doi.org/10.1086/377187

Atkinson, D., 1994. Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms. Advances in Ecological Research 25:1-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3

Atkinson, D., S. A. Morley & R. N. Hughes, 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply? Evolution & Development 8(2):202-214 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x

Audzijonyte, A., D. R. Barneche, A. R. Baudron, J. Belmaker, T. D. Clark, C. T. Marshall, J. R. Morrongiello & I. van Rijn, 2019. Is oxygen limitation in warming waters a valid mechanism to explain decreased body sizes in aquatic ectotherms? Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(2):64-77 https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12847

Bazin, S., Hemmer-Brepson, C., Logez, M., Sentis, A. & Daufresne, M. 2023. Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms. HAL, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3

Berrigan, D. & E. L. Charnov, 1994. Reaction norms for age and size at maturity in response to temperature – a puzzle for life historians. Oikos 70:474-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545787

Daufresne, M., K. Lengfellner & U. Sommer, 2009. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106(31):12788-93 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902080106

Forster, J., A. G. Hirst & D. Atkinson, 2012. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(47):19310-19314. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210460109

Hessen, D. O., P. D. Jeyasingh, M. Neiman & L. J. Weider, 2010. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004

Kozłowski, J., M. Czarnoleski & M. Dańko, 2004. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold? Integrative and Comparative Biology 44(6):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.480

Leiva, F. P., P. Calosi & W. C. E. P. Verberk, 2019. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374:20190035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0035

Ohlberger, J., 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body szie - from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12098

Verberk, W. C. E. P., D. Atkinson, K. N. Hoefnagel, A. G. Hirst, C. R. Horne & H. Siepel, 2021. Shrinking body sizes in response to warming: explanations for the temperature-size rule with special emphasis on the role of oxygen. Biological Reviews 96:247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12653

Woods, H. A., 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. American Zoologist 39:244-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.2.244