COULON Aurélie

- CESCO & CEFE, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris, France

- Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Preregistrations, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 5

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 5

Bayesian reinforcement learning models reveal how great-tailed grackles improve their behavioral flexibility in serial reversal learning experiments

Changes in behavioral flexibility to cope with environment instability: theoretical and empirical insights from serial reversal learning experiments

Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and 1 anonymous reviewerBehavioral flexibility, i.e. the “ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023), appears as one of the crucial elements of responses of animal species to changing environments. Behavioral flexibility can change within the life of individuals, depending on their experience on the degree of variability and predictability of their surrounding environment. But little is known on the cognitive processes involved in these temporal changes in behavioral flexibility within individuals.

This is what Lukas et al. (2024) investigated very thoroughly, using the framework of serial reversal learning experiments on great-tailed grackles to study different aspects of the question. Behavioral flexibility as involved in serial reversal learning experiments was previously modeled as being made of two primary parameters: the rate of updating associations, phi (i.e. how fast individuals learn the associations between a cue and its associated reward or danger); and the sensitivity to the learned associations, lambda (i.e. how strong do individuals make their choices based on the associations they learned).

Lukas et al. (2024)* used a Bayesian reinforcement model to infer phi and lambda in individuals going through serial reversal learning experiments, to understand which of these two parameters explains most of the variation in grackle performance in serial reversal learning, how correlated they are, how they can change along time depending on an individual’s experience, how variable they can be among individuals, and whether they can predict performance in other contexts. But beforehand, the authors used an individual-based model to assess the ability of the Bayesian reinforcement model to correctly assess phi and lambda in their experimental design. They also used the Bayesian model to infer the range of values of phi and lambda an individual needs to exhibit to reduce errors in the serial reversal learning experiment.

Among other results, this study shows that in a context of rapidly changing but strongly reliable cues, the variation in the success of grackles is more associated with the rate of updating associations (phi) than the sensitivity to learned associations (lambda). Besides, phi increased within individuals along the serial reversal learning experiment, while lambda only slightly decreased. However, it is very interesting to note that different approaches could be adopted by different individuals through the training, leading them eventually to the same final performance: slightly different combinations of changes in lambda and phi lead to different behaviours but compensate each other in the end in the final success rate.

This study provides exciting insights into the cognitive processes involved in how changes in behavioral flexibility of individuals can happen in this type of serial learning experiments. But it also offers interesting openings to understand the mechanisms by which behavioral flexibility can change in the wild, helping individuals to cope with rapidly changing environments.

* Lukas et al. (2024) presents a post-study of the preregistered study Logan et al. (2019) that was peer-reviewed and received an In Principle Recommendation for PCI Ecology (Coulon 2019; the initial preregistration was split into 3 post-studies). A pre-registered study is a study in which context, aims, hypotheses and methodologies have been written down as an empirical paper, peer-reviewed and pre-accepted before research is undertaken. Pre-registrations are intended to reduce publication bias and reporting bias.

References

Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019

Logan, CJ, Lukas D, Bergeron L, Folsom M, McCune, K. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In Principle Acceptance by PCI Ecology of the Version on 6 Aug 2019. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html

Dieter Lukas, Kelsey B. McCune, Aaron P. Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Maggie MacPherson, Benjamin M. Seitz, Augustus Sevchik, Corina J. Logan (2024) Bayesian reinforcement learning models reveal how great-tailed grackles improve their behavioral flexibility in serial reversal learning experiments. ecoevoRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/4ycps

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach

Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.

Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWorldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity.

Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets.

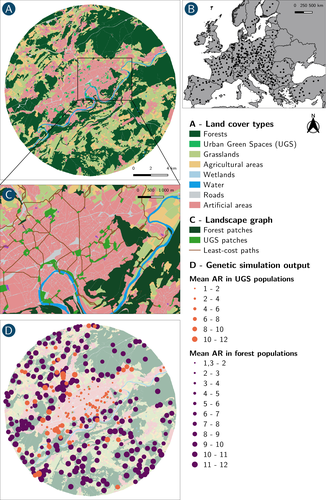

In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities.

The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow.

One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches.

Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities.

References

Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012767

Miles, L. S., Dyer, R. J., and Verrelli, B. C. (2018). Urban hubs of connectivity: Contrasting patterns of gene flow within and among cities in the western black widow spider. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 285(1884):20181224. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1224

Savary P., Tannier C., Foltête J.-C., Bourgeois M., Vuidel G., Khimoun A., Moal H., and Garnier S. (2024). How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41.

Schoville, S. D., Widmer, I., Deschamps-Cottin, M., and Manel, S. (2013). Morphological clines and weak drift along an urbanization gradient in the butterfly, Pieris rapae. PLoS ONE, 8(12):e83095.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083095

Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility

Do reversal learning methods measure behavioral flexibility?

Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha RameshAssessing the reliability of the methods we use in actually measuring the intended trait should be one of our first priorities when designing a study – especially when the trait in question is not directly observable and is measured through a proxy.

This is the case for cognitive traits, which are often quantified through measures of behavioral performance. Behavioral flexibility is of particular interest in the context of great environmental changes that a lot of populations have to experiment. This type of behavioral performance is often measured through reversal learning experiments (Bond 2007). In these experiments, individuals first learn a preference, for example for an object of a certain type of form or color, associated with a reward such as food. The characteristics of the rewarded object then change, and the individuals hence have to learn these new characteristics (to get the reward). The time needed by the individual to make this change in preference has been considered a measure of behavioral flexibility.

Although reversal learning experiments have been widely used, their construct validity to assess behavioral flexibility has not been thoroughly tested. This was the aim of McCune and collaborators' (2023) study, through the test of the repeatability of individual performance within and across contexts of reversal learning, in the great-tailed grackle.

This manuscript presents a post-study of the preregistered study* (Logan et al. 2019) that was peer-reviewed and received an In Principle Recommendation for PCI Ecology (Coulon 2019; the initial preregistration was split into 3 post-studies).

Using 34 great-tailed grackles wild-caught in Tempe, Arizona (USA), the authors tested in aviaries 2 hypotheses:

- First, that the behavioral flexibility measured by reversal learning is repeatable within individuals across sessions of the same experiment;

- Second, that there is repeatability of the measured behavioral flexibility (within individuals) across different types of reversal learning experiments (context).

The first hypothesis was tested by measuring the repeatability of the time needed by individuals to switch color preference in a color reversal learning task (colored tubes), over serial sessions of this task. The second one was tested by measuring the time needed by individuals to switch solutions, within 3 different contexts: (1) colored tubes, (2) plastic and (3) wooden multi-access boxes involving several ways to access food.

Despite limited sample sizes, the results of these experiments suggest that there is both temporal and contextual repeatability of behavioral flexibility performance of great-tailed grackles, as measured by reversal learning experiments.

Those results are a first indication of the construct validity of reversal learning experiments to assess behavioral flexibility. As highlighted by McCune and collaborators, it is now necessary to assess the discriminant validity of these experiments, i.e. checking that a different performance is obtained with tasks (experiments) that are supposed to measure different cognitive abilities.

* A pre-registered study is a study in which context, aims, hypotheses and methodologies have been written down as an empirical paper, peer-reviewed and pre-accepted before research is undertaken. Pre-registrations are intended to reduce publication bias and reporting bias.

REFERENCES

Bond, A. B., Kamil, A. C., & Balda, R. P. (2007). Serial reversal learning and the evolution of behavioral

flexibility in three species of north american corvids (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus, Nucifraga columbiana,

Aphelocoma californica). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 121 (4), 372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.121.4.372

Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019

Logan, CJ, Lukas D, Bergeron L, Folsom M, & McCune, K. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In Principle Acceptance by PCI Ecology of the Version on 6 Aug 2019. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html

McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ (2023) Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59K

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context

An experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativeness

Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewerWhether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014).

The post-study manuscript by Logan et al. (2023) proposes to test flexibility manipulability, and the relationship between flexibility and innovativeness. The authors did so with an experimental study on great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), an expanding species in the US, known to be flexible.

The authors used serial reversal learning to investigate (1) whether behavioral flexibility, as measured by reversal learning using tubes of different shades, is manipulable; (2) whether manipulating (improving/training) behavioral flexibility improves flexibility and innovativeness in new contexts; (3) the type of learning strategy used by the individuals throughout the serial reversals.

The study described in this manuscript was pre-registered in Logan et al. (2019) and received in-principle recommendation on 26 Mar 2019 (Coulon 2019). One hypothesis from this original preregistration will be treated in a separate manuscript.

Among several interesting results, what I found most striking is that flexibility, in this species, seems to be a trait that is acquired by experience (vs. inherent to the individual). This opens exciting interrogations on the role of social learning, and on the impact of rapid environmental changes (which may force the individuals to experiment new ways to access to resources, for example), on individual flexibility and adaptability to new conditions.

REFERENCES

Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019

Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027

Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019)

Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context? In Principle Recommendation 2019. PCI Ecology. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html

Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs

Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context?

Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes

Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Andrea GriffinBehavioral flexibility is a key for species adaptation to new environments. Predicting species responses to new contexts hence requires knowledge on the amount to and conditions in which behavior can be flexible. This is what Logan and collaborators propose to assess in a series of experiments on the great-tailed grackles, in a context of rapid range expansion. This pre-registration is integrated into this large research project and concerns more specifically the manipulability of the cognitive aspects of behavioral flexibility. Logan and collaborators will use reversal learning tests to test whether (i) behavioral flexibility is manipulatable, (ii) manipulating flexibility improves flexibility and problem solving in a new context, (iii) flexibility is repeatable within individuals, (iv) individuals are faster at problem solving as they progress through serial reversals. The pre-registration carefully details the hypotheses, their associated predictions and alternatives, and the plan of statistical analyses, including power tests. The ambitious program presented in this pre-registration has the potential to provide important pieces to better understand the mechanisms of species adaptability to new environments.