ASTEGIANO Julia

- WITRAL, IADIZA (CONICET), Mendoza, Argentina

- Agroecology, Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism, Food webs, Interaction networks, Landscape ecology, Meta-analyses, Pollination, Preregistrations, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Theoretical ecology

- recommender, manager

Recommendations: 2

Reviews: 2

Recommendations: 2

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices

Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persist

Recommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clélia Sirami and Diego GurvichAgricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ.

In this vein, the study of Poinas et al. (2024) can be considered a key contribution. It exemplifies how agricultural intensification practiced in the context of climate change can constrain the potential of agricultural field margin flora to cope with climatic variations. The authors found that the incidence of plant strategies better adapted to climate change (conservative/stress-tolerant and Mediterranean species) increased with higher temperatures and lower soil moisture, and with lower intensity of margin management. In contrast, the incidence of ruderal species decreased with climate change. Thus, increasing or even maintaining current levels of agricultural intensification may affect the potential of French agriculture to move to sustainable process-based agricultures because of the reduction of plant diversity, particularly of vegetation better adapted to climate change.

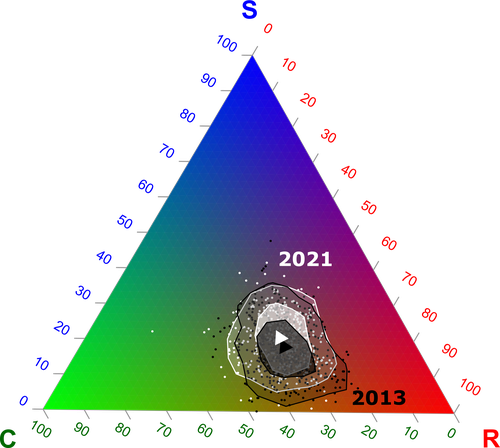

By using an impressive dataset spanning 9 years and 555 agricultural margins in continental France, Poinas et al. (2024) investigated temporal changes in climatic variables (temperature and soil moisture), agricultural practices (herbicide and fertilizers quantity, the frequency of margin mowing or grinding), plant taxonomical and functional diversity, plant strategies (Grime 1977, 1988) and relationships between these temporal changes. Temporal changes in plant strategies were associated with those observed in climatic variables and agricultural practices. Even such associations seem to be mediated by spatial changes, as described in the supplementary material and in their most recent article (Poinas et al. 2023), changes in climatic variables registered in a decade shaped plant strategies and therefore the diversity and functional potential of agricultural field margins. These results are clearly synthesized in Figures 6 and 7 of the present contribution.

As shown by Poinas et al. (2024), in the context of climate change, decreasing agricultural intensification will produce more diverse agricultural field margins by promoting the persistence of plant species better adapted to higher temperatures and lower soil moisture. Thus, adopting other agricultural practices (e.g., agroforestry, agroecology) will produce territories with a higher potential to move to sustainable processes-based agricultures that may better cope with climate change by harboring higher biocultural diversity (Altieri et al. 2015).

References

Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013

Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2

Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005

Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244

Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14

Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain.

Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003

Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956

Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715

Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species?

Understanding geographic range expansions in human-dominated landscapes: does behavioral flexibility modulate flexibility in foraging and social behavior?

Recommended by Julia Astegiano and Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Esther Sebastián GonzálezWhich biological traits modulate species distribution has historically been and still is one of the core questions of the macroecology and biogeography agenda [1, 2]. As most of the Earth surface has been modified by human activities [3] understanding the strategies that allow species to inhabit human-dominated landscapes will be key to explain species geographic distribution in the Anthropocene. In this vein, Logan et al. [4] are working on a long-term and integrative project aimed to investigate how great-tailed grackles rapidly expanded their geographic range into North America [4]. Particularly, they want to determine which is the role of behavioral flexibility, i.e. an individual’s ability to modify its behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience [5], in rapid geographic range expansions. The authors are already working in a set of complementary questions described in pre-registrations that have already been recommended at PCI Ecology: (1) Do individuals with greater behavioral flexibility rely more on causal cognition [6]? (2) Which are the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility [7]? (3) Does the manipulation of behavioral flexibility affect exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity [8]? (4) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility [9]?

In this new pre-registration, they aim to determine whether the more behaviorally flexible individuals have more flexible foraging behaviors (i.e. use a wider variety of foraging techniques in the wild and eat a larger number of different foods), habitat use (i.e. higher microhabitat richness) and social relationships (i.e., are more likely to have a greater number of bonds or stronger bonds with other individuals; [4]). The project is ambitious, combining both the experimental characterization of individuals’ behavioral flexibility and the field characterization of the foraging and social behavior of those individuals and of wild ones.

The current great-tailed grackles project will be highly relevant to understand rapid geographic range expansions in a changing world. In this vein, this pre-registration will particularly help to go one step further in our understanding of behavioral flexibility as a determinant of species geographic distribution. Logan et al. [4] pre-registration is very well designed, main and alternative hypotheses have been thought and written and methods are presented in a very detailed way, which includes the R codes that authors will use in their analyses. Authors have answered in a very detailed way each comment that reviewers have pointed out and modified the pre-registration accordingly, which we consider highly improved the quality of this work. That is why we strongly recommend this pre-registration and look forward to see the results.

References

[1] Gaston K. J. (2003) The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York.

[2] Castro-Insua, A., Gómez‐Rodríguez, C., Svenning, J.C., and Baselga, A. (2018) A new macroecological pattern: The latitudinal gradient in species range shape. Global ecology and biogeography, 27(3), 357-367. doi: 10.1111/geb.12702

[3] Newbold, T., Hudson, L. N., Hill, S. L. L., Contu, S., Lysenko, I., Senior, R. A., et al. (2015). Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature, 520(7545), 45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature14324

[4] Logan CJ, McCune K, Bergeron L, Folsom M, Lukas D. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexforaging.html

[5] Mikhalevich, I., Powell, R., and Logan, C. (2017). Is Behavioural Flexibility Evidence of Cognitive Complexity? How Evolution Can Inform Comparative Cognition. Interface Focus 7: 20160121. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121.

[6] Fronhofer, E. (2019) From cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroecological patterns. Peer Community in Ecology, 100014. doi: 10.24072/pci.ecology.100014

[7] Vogel, E. (2019) Adapting to a changing environment: advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility. Peer Community in Ecology, 100016. doi: 10.24072/pci.ecology.100016

[8] Van Cleve, J. (2019) Probing behaviors correlated with behavioral flexibility. Peer Community in Ecology, 100020. doi: 10.24072/pci.ecology.100020

[9] Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. doi: 10.24072/pci.ecology.100019

Reviews: 2

Crop productivity of Central European Permaculture is within the range of organic and conventional agriculture.

Permaculture, a promising alternative to conventional agriculture

Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Paulina Kramarz, Leda Lorenzo Montero and 1 anonymous reviewerAs mankind develops increasingly efficient and productive methods of agriculture and food production, we have reached a point where intensive agriculture threatens several aspects of life on Earth, negatively affecting biodiversity, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles and water reservoirs, while producing considerable amounts of greenhouse gases (Krebs and Bach, 2018). There was a need to develop farming methods that were friendly to both nature and people, producing good quality, healthy food without destroying the environment. The idea of permaculture, a concept of sustainable agriculture based on methods learned directly from nature, originated in the 1960s, invented and developed by Bruce Charles Mollison and David Holmgren (Mollison and Holmgren 1979, Mollison et al. 1991, Holmgren 2002). Although the idea of permaculture has attracted scientific interest, the representation in published studies is unbalanced in favour of positive ecological and sociological effects, with much less presence of rigorous experimental testing (Ferguson and Lovell 2014, Reiff et al. 2024a).

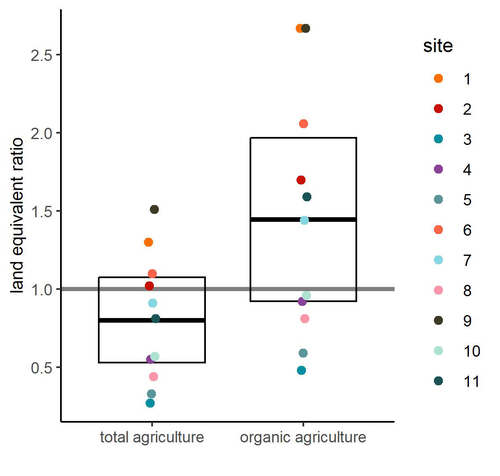

Reiff et al. (2024b) provided the first large-scale empirical evidence of permaculture production outcomes for Central Europe. Based on results from 11 commercial permaculture sites, situated mostly in Germany but also in Switzerland and Luxembourg, the authors found that food production from permaculture sites was on average comparable to that from conventional and organic agriculture. The authors were very thorough in pointing out the issues that could potentially affect their results and which need further testing.

Among these, the authors highlight the considerable variability between the 11 sites studied, which may suggest that different permacultures should differ in details according to their specificity - an interesting issue that definitely requires further study. The other factor that the authors point out that could have influenced the results and led to an underestimation of the real potential is the age of the permaculture sites. The sites from the study were relatively young, and their potential can be expected to increase with time.

It is important to note that the results are mostly applicable to vegetables, as vegetable production accounted for 94% of production in the permaculture sites (followed by tree crops, 6%, and soft fruit production, 0.5%). There is therefore a need to include other types of crops produced in further studies of this type.

To date, the results informing permaculture food production are urgently needed and should cover the potentially wide range of geographical regions and crops produced. The results of Reiff et al. (2025) show that rigorous testing of this issue is demanding, but the authors provide a very sound "road map" of further steps.

Literature:

Ferguson R. S. and Lovell S. T. 2014. Permaculture for agroecology: design, movement, practice, and worldview. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 34, 251-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6

Holmgren D. 2002. Permaculture: Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Holmgren Design Services, pp. 320.

Krebs J. and Bach S. 2018. Permaculture – scientific evidence of principles for the agroecological design of farming systems. Sustainability 10, 3218, https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093218

Mollison B. C. and Holmgren D. 1979. Permaculture One: A Perennial Agricultural System for Human Settlements. Tagari Publications, pp. 136.

Mollison B. C., Slay, R. M. and Jeeves A. 1991. Introduction to permaculture. Tagari Publications, pp. 198.

Reiff J., Jungkunst H. F., Mauser K. M., Kampel S., Regending S., Rösch V., Zaller J. G. and Entling M. H. 2024a. Permaculture enhances carbon stocks, soil quality and biodiversity in Central Europe. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01405-8

Reiff J., Jungkunst H. F., Antes N. and Entling M. H. 2024b. Crop productivity of Central European Permaculture is within the range of organic and conventional agriculture. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.09.611985

Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach

Towards model-guided organic farming expansion for crop pest management

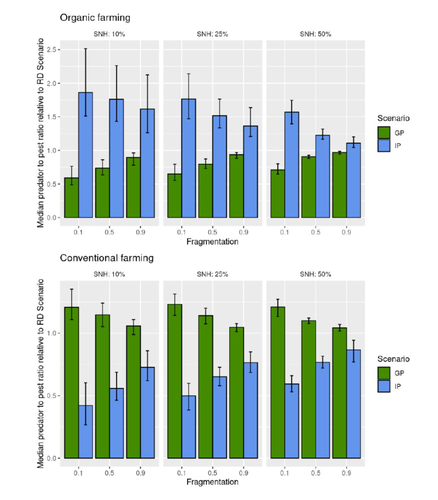

Recommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain BartReduce the impact the intensification of human activities has on the environmental is the challenge the humanity faces today, a major challenge that could be compared to climbing Everest without an oxygen supply. Indeed, over-population, pollution, burning fossil fuels, and deforestation are all evils which have had hugely detrimental effects on the environment such as climate change, soil erosion, poor air quality, and scarcity of drinking water to name but a few. In response to the ever-growing consumer demand, agriculture has intensified massively along with a drastic increase in the use of chemicals to ensure an adequate food supply while controlling crop pests. In this context, to address the disastrous effects of the intensive usage of pesticides on both human health and biodiversity, organic farming (OF) revealed as a miracle remedy with multiple benefits. Delattre et al. (2023) present a powerful modelling approach to decipher the crossed effects of the landscape structure and the OF expansion scenario on the pest abundance, both in organic and conventional (CF) crop fields. To this end, the authors ingeniously combined a grid-based landscape model with a spatially explicit predator-pest model. Based on an extensive in silico simulation process, they explore a diversity of landscape structures differing in their amount of semi-natural habitats (SHN) and in their fragmentation, to finally propose a ranking of various expansion scenarios according to the pest control methods in organic farming as well as to the pest and predators’ dissemination capacities. In total, 9 landscape structures (3 proportions of SHN x 3 fragmentation levels) were crossed with 3 expansion scenarios (RD = a random distribution of OF and CF in the grid; IP = isolated CF are converted; GP = CF within aggregates are converted), 4 pest management practices, 3 initial densities and 36 biological parameter combinations driving the predator’ and pest’s population dynamics. This exhaustive exploration of possible combinations of landscape and farming practices highlighted the main drivers of the various OF expansion scenarios, such as increased spillover of predators in isolated OF/CF fields, increased pest management efficiency in large patches of CF and the importance of the distance between OF and CF. In the end, this study brings to light the crucial role that landscape planning plays when OF practices have limited efficiency on pests. It also provides convincing arguments to the fact that converting to organic isolated CF as a priority seems to be the most promising scenario to limit pest densities in CF crops while improving predator to pest ratios (considered as a proxy of conservation biological control) in OF ones without increasing pest densities. Once further completed with model calibration validation based on observed life history traits data for both predators and pests, this work should be very helpful in sustaining policy makers to convince farmers of engaging in organic farming.

REFERENCES

Delattre T, Memah M-M, Franck P, Valsesia P, Lavigne C (2023) Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach. bioRxiv, 2022.05.31.494006, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006