Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

07 Nov 2024

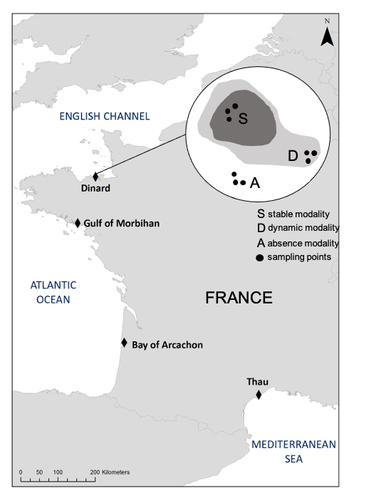

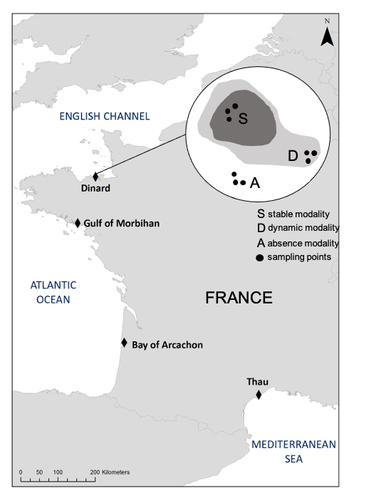

A dataset of Zostera marina and Zostera noltei structure and functioning in four sites along the French coast over a period of 18 monthsÉlise Lacoste, Vincent Ouisse, Nicolas Desroy, Lionel Allano, Isabelle Auby, Touria Bajjouk, Constance Bourdier, Xavier Caisey, Marie-Noelle de Casamajor, Nicolas Cimiterra, Céline Cordier, Amélia Curd, Lauriane Derrien, Gabin Droual, Stanislas F. Dubois, Élodie Foucault, Aurélie Foveau, Jean-Dominique Gaffet, Florian Ganthy, Camille Gianaroli, Rachel Ignacio-Cifré, Pierre-Olivier Liabot, Gregory Messiaen, Claire Meteigner, Benjamin Monnier, Robin Van Paemelen, Marine Pasquier, Loic Rigouin, Cla... https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10425140A functional ecology reference database on the populations of two species of Zoostera along french coastsRecommended by Gudrun Bornette based on reviews by Antoine Vernay, Sara PUIJALON and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Antoine Vernay, Sara PUIJALON and 1 anonymous reviewer

Seagrass beds are in a poor state of conservation and the ecological function of these plant communities is poorly assessed. Four zones of eelgrass beds (Zostera marina and Zostera noltei) were described in terms of the morphology of the plant populations and the associated fauna. At the same time, parameters related to the functioning of these ecosystems were quantified (benthic fluxes of oxygen, carbon and nutrients) over a two-year cycle. The article provides the databases collected and provides the main characteristics of these habitats for the measured parameters. The work provides a reference database on the Zoostera beds of french coastal areas, outlining the ecological contrasts between both ecosystems. This database can on the one hand contribute to help management and restoration of these habitats, and on the other hand provide a reference state of their ecology, with a view to long-term monitoring. References Élise Lacoste, Vincent Ouisse, Nicolas Desroy, Lionel Allano, Isabelle Auby, Touria Bajjouk, Constance Bourdier, Xavier Caisey, Marie-Noelle de Casamajor, Nicolas Cimiterra, Céline Cordier, Amélia Curd, Lauriane Derrien, Gabin Droual, Stanislas F. Dubois, Élodie Foucault, Aurélie Foveau, Jean-Dominique Gaffet, Florian Ganthy, Camille Gianaroli, Rachel Ignacio-Cifré, Pierre-Olivier Liabot, Gregory Messiaen, Claire Meteigner, Benjamin Monnier, Robin Van Paemelen, Marine Pasquier, Loic Rigouin, Claire Rollet, Aurélien Royer, Laura Soissons, Aurélien Tancray, Aline Blanchet-Aurigny (2023) A dataset of Zostera marina and Zostera noltei structure and functioning in four sites along the French coast over a period of 18 months.. Zenodo, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10425140 | A dataset of *Zostera marina* and *Zostera noltei* structure and functioning in four sites along the French coast over a period of 18 months | Élise Lacoste, Vincent Ouisse, Nicolas Desroy, Lionel Allano, Isabelle Auby, Touria Bajjouk, Constance Bourdier, Xavier Caisey, Marie-Noelle de Casamajor, Nicolas Cimiterra, Céline Cordier, Amélia Curd, Lauriane Derrien, Gabin Droual, Stanislas F.... | <p>This manuscript describes the methodology associated with the dataset entitled: A dataset of <em>Zostera marina </em>and <em>Zostera noltei </em>structure and functioning in four sites along the French coast over a period of 18 months. The data... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Ecosystem functioning, Marine ecology | Gudrun Bornette | 2023-12-21 11:48:43 | View | |

07 Nov 2024

Using multiple datasets to account for misalignment between statistical and biological populations for abundance estimationMichelle L. Kissling, Paul M. Lukacs, Kelly Nesvacil, Scott M. Gende, Grey W. Pendleton https://doi.org/10.32942/X2W03TDiving into detection process to solve sampling and abundance issues in a cryptic speciesRecommended by Guillaume Souchay based on reviews by Michael Schaub, Chloé Nater and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Michael Schaub, Chloé Nater and 1 anonymous reviewer

Estimating population parameters is critical for analysis and management of wildlife populations. Drawing inference at the population level requires a robust sampling scheme and information about the representativeness of the studied population (Williams et al. 2002). In their textbook, Williams et al. (see chapter 5, 2002) listed several sampling issues, including both temporal and spatial heterogeneity and especially imperfect detection. Several methods, either sampling-based or model-based can be used to circumvent these issues. In their paper, Kissling et al. (2024) addressed the case of the Kittlitz’s murrelet (Brachyramphus brevirostris), a cryptic ice-associated seabird, combining spatial variation in its distribution, temporal variation in breeding propensity, imperfect detection and logistical challenges to access the breeding area. The Kittlitz’s murrelet is thus the perfect species to illustrate common issues and logistical difficulties to implement a standard sampling scheme. The authors proposed a modelling framework unifying several datasets from different surveys to extract information on each step of the detection process: the spatial match between the targeted population and the sampled population, the probability of presence in the sample area, the probability of availability given presence in the sample area and finally, the probability of detection given presence and availability. All these components were part of the framework to estimate abundance and trend for this species. They took advantage of a radiotracking survey during several years to inform spatial match and probability of presence. They performed a behavioural experiment to assess the probability of availability of murrelets given it was present in sampling area, and they used a conventional distance-sampling boat survey to estimate detection of individuals. This is worth noting that the most variable components were the probability of presence in the sample area, with a global mean of 0.50, and the probability of detection given presence and availability ranging from 0.49 to 0.77. The estimated trend for Kittlitz’s murrelet was negative and all the information gathered in this study will be useful for future conservation plan. Coupling a decomposition of the detection process with different data sources was the key to solve problems raised by such “difficult” species, and the paper of Kissling et al. (2024) is a good way to follow for other species, allowing to inform the detection components for the targeted species - and also for our global understanding of detection process, and to infer about the temporal trend of species of conservation concern. References Williams, B. K., Nichols, J. D., and Conroy, M. J. (2002). Analysis and management of animal populations. Academic Press. Michelle L. Kissling, Paul M. Lukacs, Kelly Nesvacil, Scott M. Gende, Grey W. Pendleton (2024) Using multiple datasets to account for misalignment between statistical and biological populations for abundance estimation. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.32942/X2W03T | Using multiple datasets to account for misalignment between statistical and biological populations for abundance estimation | Michelle L. Kissling, Paul M. Lukacs, Kelly Nesvacil, Scott M. Gende, Grey W. Pendleton | <p style="text-align: justify;">A fundamental aspect of ecology is identifying and characterizing population processes. Because a complete census is rare, we almost always use sampling to make inference about the biological population, and the par... |  | Euring Conference, Population ecology | Guillaume Souchay | 2023-12-28 19:59:21 | View | |

30 Oct 2024

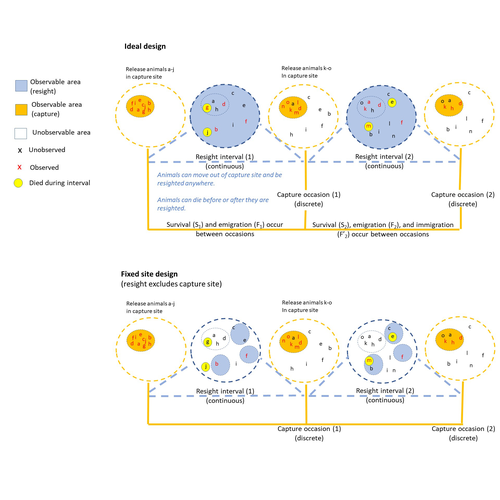

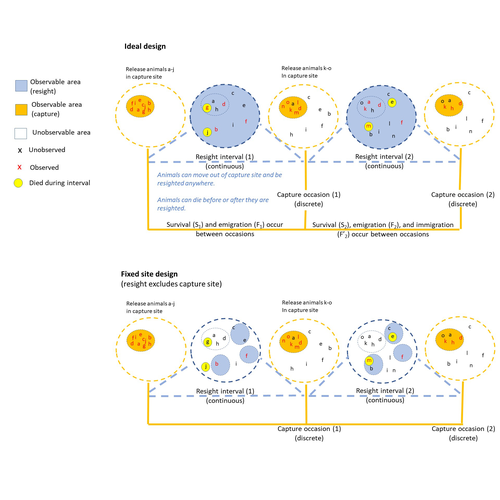

The importance of sampling design for unbiased estimation of survival using joint live-recapture and live resight modelsMaria C. Dzul, Charles B. Yackulic, William L. Kendall https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.13414In the quest for estimating true survivalRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Rémi Fay and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rémi Fay and 1 anonymous reviewer

Accurately estimating survival rate and identifying the drivers of its variation is essential for our understanding of population dynamics and life history strategies (Sæther and Bakke 2000), as well as for population management and conservation (Francis et al. 1998, Doherty et al. 2014). Many studies estimate survival from capture–recapture data using the Cormack–Jolly–Seber (CJS) model (Lebreton et al. 1992). However, survival estimates are confounded with permanent emigration from the study area, which can be particularly problematic for mobile species. This is problematic, not only because CJS models under estimate true survival in populations where permanent emigration occurs (i.e. they estimate “apparent” survival), but also because some factors of interest may affect both survival and emigration (e.g., habitat quality, Paquet et al. 2020), leaving the interpretation of results challenging, for example in terms of management decisions. Several methods have been developed to account for permanent emigration when estimating survival, for example by jointly analyzing CMR data with data on individuals’ locations at each capture/resighting site (to estimate their dispersal distances; Schaub and Royle 2013, Badia Boher et al. 2023), with telemetry data (Powel et al. 2000), mark recovery data (Burnham 1993, Fay et al. 2019), or with live-resight data (Barker 1997). The Barker joint live-recapture/live-resight (JLRLR) model can estimate survival when resight data are continuous over a long interval and from a larger area than the capture recapture data. This model becomes particularly promising with the growing collection of data from citizen science, or remote detection tools (Dzul et al. 2023). However, as pointed out by Dzul et al., this model assumes that resight probability is homogeneous across the area where individuals can move, and this assumption is likely violated for example because of non-random movements or because of non-random location of resighting sites. In their manuscript, Dzul et al. performed a thorough simulation study to evaluate the accuracy of survival estimates from JLRLR models under various study designs regarding the location of resight sites (global, random, fixed including the capture site, and fixed excluding the capture site). They simulated data with varying survival and movement values, varying recapture and resight probabilities, and varying sample sizes. Finally, they also developed and fitted a multi state version of the JLRLR model. They show that JLRLR models performed better than CJS models. Survival estimates were still often biased (either positively or negatively) but they were less biased when sesight sites were randomly located (rather than at fixed locations), when recapture sites were included in the resighting design, and when using the multi state JLRLR model they developed. This study highlights (multistate) JLRLR models as an alternative to CJS models one should consider when auxiliary resight data can be collected. Moreover, it shows the importance of evaluating not only model performance, but also the efficiency of alternative sampling designs before choosing one for our studies. Hopefully, this study will help the authors and other researchers making a more informed and efficient choice of model and design to estimate survival in their study populations. References Jaume A. Badia-Boher, Joan Real, Joan Lluís Riera, Frederic Bartumeus, Francesc Parés, Josep Maria Bas, and Antonio Hernández-Matías. Joint estimation of survival and dispersal effectively corrects the permanent emigration bias in mark-recapture analyses. (2023) Scientific reports 13, no. 1: 6970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32866-0 Richard J Barker (1997) Joint modeling of live-recapture, tag-resight, and tag-recovery data. Biometrics: 666-677. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533966 Kenneth P. Burnham (1993) Marked Individuals in the Study of Bird Populations (ed. J.D. Lebreton), pp. 199–213. Birkhäuser, Basel Kevin E. Doherty, David E. Naugle, Jason D. Tack, Brett L. Walker, Jon M. Graham, Jeffrey L. Beck (2014) Linking conservation actions to demography: grass height explains variation in greater sage‐grouse nest survival. Wildlife biology 20, no. 6 : 320-325. https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00004 Maria C. Dzul, Charles B. Yackulic, William L. Kendall (2023) The importance of sampling design for unbiased estimation of survival using joint live-recapture and live resight models. arXiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.13414 Rémi Fay, Stephanie Michler, Jacques Laesser, and Michael Schaub (2019) Integrated population model reveals that kestrels breeding in nest boxes operate as a source population. Ecography 42, no. 12: 2122-2131. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04559 Charles M. Francis, John R. Sauer, Jerome R. Serie (1998) Effect of restrictive harvest regulations on survival and recovery rates of American black ducks. The Journal of Wildlife Management : 1544-1557. https://doi.org/10.2307/3802021 Jean-Dominique Lebreton, Kenneth P. Burnham, Jean Clobert, David R. Anderson (1992) Modeling survival and testing biological hypotheses using marked animals: a unified approach with case studies. Ecological monographs 62.1: 67-118. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937171 Matthieu Paquet, Debora Arlt, Jonas Knape, Matthew Low, Pär Forslund, and Tomas Pärt (2020) Why we should care about movements: Using spatially explicit integrated population models to assess habitat source–sink dynamics. Journal of Animal Ecology 89, no. 12: 2922-2933. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13357 Larkin A. Powell, Michael J. Conroy, James E. Hines, James D. Nichols, and David G. Krementz. Simultaneous use of mark-recapture and radiotelemetry to estimate survival, movement, and capture rates. (2000) The Journal of Wildlife Management : 302-313. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803003 Bernt-Erik Sæther, Øyvind Bakke (2000) Avian life history variation and contribution of demographic traits to the population growth rate. Ecology 81.3 : 642-653. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0642:ALHVAC]2.0.CO;2 Michael Schaub, J. Andrew Royle. Estimating true instead of apparent survival using spatial Cormack–Jolly–Seber models (2014) Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5, no. 12: 1316-1326. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12134 | The importance of sampling design for unbiased estimation of survival using joint live-recapture and live resight models | Maria C. Dzul, Charles B. Yackulic, William L. Kendall | <p>Survival is a key life history parameter that can inform management decisions and life history research. Because true survival is often confounded with permanent and temporary emigration from the study area, many studies must estimate apparent ... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Euring Conference, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-12-22 22:31:07 | View | |

30 Oct 2024

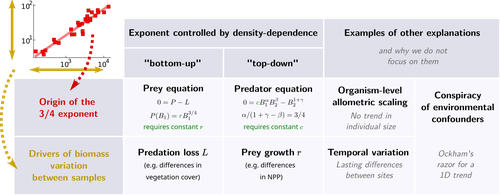

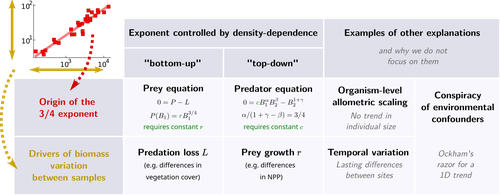

General mechanisms for a top-down origin of the predator-prey power lawOnofrio Mazzarisi, Matthieu Barbier, Matteo Smerlak https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.04.588057Rethinking Biomass Scaling in Predators-Preys ecosystemsRecommended by Samir Simon Suweis based on reviews by Samraat Pawar and 1 anonymous reviewerThe study titled “General mechanisms for a top-down origin of the predator-prey power law” provides a fresh perspective on the classic predator-prey biomass relationship often observed in ecological communities. Traditionally, predator-prey dynamics have been examined through a bottom-up lens, where prey biomass and energy availability dictate predator populations. However, this study, which instead explores the possibility of a top-down origin for predator-prey power laws, offers a new dimension to our understanding of ecosystem regulation and raises questions about how predator-driven interactions might influence biomass scaling laws independently of prey abundance. Ecologists have long noted that ecosystems often exhibit sublinear scaling between predator and prey biomasses. This pattern implies that predator biomass does not increase proportionally with prey biomass but at a slower rate, leading to a power-law relationship. Traditional explanations, such as those discussed by Peters (1983) and McGill (2006), have linked this to bottom-up processes, suggesting that increases in prey availability support, but do not fully translate to, larger predator populations due to energy losses in the trophic cascade. However, these explanations assume prey abundance as the principal driver. This new work raises an intriguing question: could density-dependent predator interactions, such as competition and interference, be equally or more important in creating this observed power law? The authors hypothesized that density-dependent predator interactions might independently control predator biomass, even when prey is abundant. To test this, they combined predator and prey biomass dynamics equation based on a modified Lotka-Volterra model with agent-based models (ABMs) on a spatial grid, simulating predator-prey populations under varying environmental gradients and density-dependent conditions. These models allowed them to incorporate predator-specific factors, such as intraspecific competition (predator self-regulation) and predation interference, offering a quantitative framework to observe whether these top-down dynamics could indeed explain the observed biomass scaling independently of prey population changes. Their results show that density-dependent predator dynamics, particularly at high predator densities, can yield sublinear scaling in predator-prey biomass relationships. This aligns well with empirical data, such as African mammalian ecosystems where predators seem to self-regulate under high prey availability by competing amongst themselves rather than expanding in direct proportion to prey biomass. Such findings support a shift from bottom-up perspectives to a model where top-down processes drive population regulation and biomass scaling. I think that the work by Mazzarisi and collaborators (2024) offers a thought-provoking twist on predator-prey dynamics and suggests that our traditional frameworks may benefit from a broader, more predator-centered focus. References 1. Onofrio Mazzarisi, Matthieu Barbier, Matteo Smerlak (2024) General mechanisms for a top-down origin of the predator-prey power law. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.04.588057 2. Peters, R. H. (1986). The ecological implications of body size (Vol. 2). Cambridge university press. 3. McGill, B. J. (2006). “A renaissance in the study of abundance.” Science, 314(5801), 770-772. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134920 | General mechanisms for a top-down origin of the predator-prey power law | Onofrio Mazzarisi, Matthieu Barbier, Matteo Smerlak | <p style="text-align: justify;">The ratio of predator-to-prey biomass density is not constant along ecological gradients: denser ecosystems tend to have fewer predators per prey, following a scaling relation known as the ``predator-prey power law'... |  | Allometry, Community ecology, Food webs, Macroecology, Theoretical ecology | Samir Simon Suweis | 2024-04-06 21:04:59 | View | |

10 Oct 2024

Large-scale spatio-temporal variation in vital rates and population dynamics of an alpine birdChloé R. Nater, Francesco Frassinelli, James A. Martin, Erlend B. Nilsen https://doi.org/10.32942/X2VP6JDo look up: building a comprehensive view of population dynamics from small scale observation through citizen scienceRecommended by Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison based on reviews by Todd Arnold and 1 anonymous reviewerPopulation ecologists are in the business of decrypting the drivers of variation in the abundance of organisms across space and time (Begon et al. 1986). Comprehensive studies of wild vertebrate populations which provide the necessary information on variations in vital rates in relation to environmental conditions to construct informative models of large-scale population dynamics are rare, ostensibly because of the huge effort required to monitor individuals across ecological contexts and over generations. In this current aim, Nater et al. (2024) are leading the way forward by combining distance sampling data collected through a large-scale citizen science (Fraisl et al. 2022) programme in Norway with state-of-the-art modelling approaches to build a comprehensive overview of the population dynamics of willow ptarmigan. Their work enhances our fundamental understanding of this system and provides evidence-based tools to improve its management (Williams et al. 2002). Even better, they are working for the common good, by providing an open-source workflow that should enable ecologists and managers together to predict what will happen to their favourite model organism when the planet throws its next curve ball. In the case of the ptarmigan, for example, it seems that the impact of climate change on their population dynamics will differ across the species’ distributional range, with a slower pace of life (sensu Stearns 1983) at higher latitudes and altitudes. On a personal note, I have often mused whether citizen science, with its inherent limits and biases, was just another sticking plaster over the ever-deeper cuts in the research budgets to finance long-term ecological research. Here, Nater et al. are doing well to convince me that we would be foolish to ignore such opportunities, particularly when citizens are engaged, motivated, with an inherent capacity for the necessary discipline to employ common protocols in a standardised fashion. A key challenge for us professional ecologists is to inculcate the next generation of citizens with a sense of their opportunity to contribute to a better understanding of the natural world. References Begon, Michael, John L Harper, and Colin R Townsend. 1986. Ecology: individuals, populations and communities. Blackwell Science. Fraisl, Dilek, Gerid Hager, Baptiste Bedessem, Margaret Gold, Pen-Yuan Hsing, Finn Danielsen, Colleen B Hitchcock, et al. 2022. Citizen Science in Environmental and Ecological Sciences. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2 (1): 64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00144-4 Chloé R. Nater, Francesco Frassinelli, James A. Martin, Erlend B. Nilsen (2024) Large-scale spatio-temporal variation in vital rates and population dynamics of an alpine bird. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.32942/X2VP6J Stearns, S.C. 1983. The influence of size and phylogeny of covariation among life-history traits in the mammals. Oikos, 41, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544261 Williams, Byron K, James D Nichols, and Michael J Conroy. 2002. Analysis and Management of Animal Populations. Academic Press. | Large-scale spatio-temporal variation in vital rates and population dynamics of an alpine bird | Chloé R. Nater, Francesco Frassinelli, James A. Martin, Erlend B. Nilsen | <p>Quantifying temporal and spatial variation in animal population size and demography is a central theme in ecological research and important for directing management and policy. However, this requires field sampling at large spatial extents and ... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation biology, Demography, Euring Conference, Landscape ecology, Life history, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Statistical ecology, Terrestrial ecology | Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison | 2024-02-02 08:54:06 | View | |

07 Oct 2024

Guidance framework to apply best practices in ecological data analysis: Lessons learned from building Galaxy-EcologyColine Royaux, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Marie Jossé, Dominique Pelletier, Olivier Norvez, Yves Reecht, Anne Fouilloux, Helena Rasche, Saskia Hiltemann, Bérénice Batut, Marc Eléaume, Pauline Seguineau, Guillaume Massé, Alan Amossé, Claire Bissery, Romain Lorrilliere, Alexis Martin, Yves Bas, Thimothée Virgoulay, Valentin Chambon, Elie Arnaud, Elisa Michon, Clara Urfer, Eloïse Trigodet, Marie Delannoy, Gregoire Loïs, Romain Julliard, Björn Grüning, Yvan Le Bras https://doi.org/10.32942/X2G033Best practices for ecological analysis are required to act on concrete challengesRecommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by Nick Isaac and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nick Isaac and 1 anonymous reviewer

A core challenge facing ecologists is to work through an ever-increasing amount of data. The accelerating decline in biodiversity worldwide, mounting pressure of anthropogenic impacts, and increasing demand for actionable indicators to guide effective policy means that monitoring will only intensify, and rely on tools that can generate even more information (Gonzalez et al., 2023). How, then, do we handle this new volume and diversity of data? This is the question Royaux et al. (2024) are tackling with their contribution. By introducing both a conceptual ("How should we think about our work?") and an operational ("Here is a tool to do our work with") framework, they establish a series of best practices for the analysis of ecological data. It is easy to think about best practices in ecological data analysis in its most proximal form: is it good statistical practice? Is the experimental design correct? These have formed the basis of many recommendations over the years (see e.g. Popovic et al., 2024, for a recent example). But the contribution of Royaux et al. focuses on a different part of the analysis pipeline: the computer science (and software engineering) aspect of it. As data grows in volume and complexity, the code needed to handle it follows the same trend. It is not a surprise, therefore, to see that the demand for programming skills in ecologists has doubled recently (Feng et al., 2020), prompting calls to make computational literacy a core component of undergraduate education (Farrell & Carrey, 2018). But beyond training, an obvious way to make computational analysis ecological data more reliable and effective is to build better tools. This is precisely what Royaux et al. have achieved. They illustrate their approach through their experience building Galaxy-Ecology, a computing environment for ecological analysis: by introducing a clear taxonomy of computing concepts (data exploration, pre-processing, analysis, representation), with a hierarchy between them (formatting, data correction, anonymization), they show that we can think about the pipeline going from data to results in a way that is more systematized, and therefore more prone to generalization. We may buckle at the idea of yet another ontology, or yet another framework, for our work, but I am convinced that the work of Royaux et al. is precisely what our field needs. Because their levels of atomization (their term for the splitting of complex pipelines into small, single-purpose tasks) are easy to understand, and map naturally onto tasks that we already perform, it is likely to see wide adoption. Solving the big, existential challenges of monitoring and managing biodiversity at the global scale requires the adoption of good practices, and a tool like Galaxy-Ecology goes a long way towards this goal. References Farrell, K.J., and Carey, C.C. (2018). Power, pitfalls, and potential for integrating computational literacy into undergraduate ecology courses. Ecol. Evol. 8, 7744-7751. Feng, X., Qiao, H., and Enquist, B. (2020). Doubling demands in programming skills call for ecoinformatics education. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 18, 123-124. | Guidance framework to apply best practices in ecological data analysis: Lessons learned from building Galaxy-Ecology | Coline Royaux, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Marie Jossé, Dominique Pelletier, Olivier Norvez, Yves Reecht, Anne Fouilloux, Helena Rasche, Saskia Hiltemann, Bérénice Batut, Marc Eléaume, Pauline Seguineau, Guillaume Massé, Alan Amossé, Claire Bissery, Rom... | <p>Numerous conceptual frameworks exist for best practices in research data and analysis (e.g. Open Science and FAIR principles). In practice, there is a need for further progress to improve transparency, reproducibility, and confidence in ecology... | Statistical ecology | Timothée Poisot | 2024-04-12 10:13:59 | View | ||

20 Sep 2024

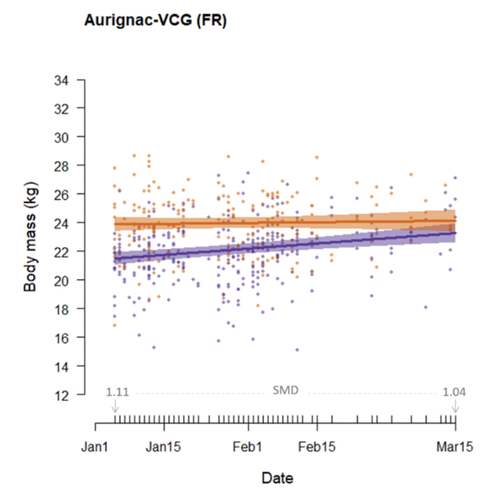

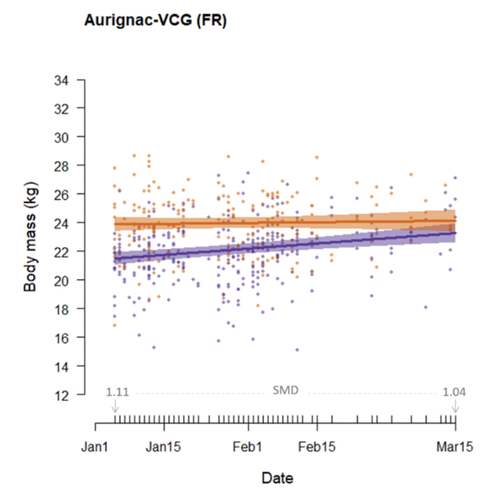

Body mass change over winter is consistently sex-specific across roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) populationsMark Hewison, Nadège Bonnot, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Petter Kjellander, Jean-François Lemaitre, Nicolas Morellet & Maryline Pellerin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.09.507329Is it sexual mass dimorphism season?Recommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by Patrick Bergeron, Philip McLoughlin and Achaz von HardenbergPolygyny is assumed to have led to the evolution of strong sexual size dimorphism (SSD) in mammals, males often being heavier or showing more developed armaments than females (Weckerly 1998; Loison et al. 1999; Pérez‐Barbería et al. 2002). SSD generally increases with the degree of polygyny of the species. However, the degree of SSD, and particularly of sexual mass dimorphism, is not fixed for each species, and differences exist between populations (Blanckenhorn et al. 2006; Cox & Calsbeek 2010) or even between seasons within populations (Rughetti & Festa‐Bianchet 2011). In this study, Hewison et al. propose that studying seasonal variation in sexual mass dimorphism and how this can be affected by winter harshness and latitude allows us to better assess the energetic costs associated with the eco-evolutionary constraints acting on each sex. To achieve their goal, Hewison et al. use a formidable, long-term dataset of over 7,000 individuals, in five roe deer populations (Capreolus capreolus), from south-west France and Sweden. According to the authors, sexual mass dimorphism should be at its lowest in early spring in this species due to a stronger trade-off between antler growth and body weight maintenance in males over winter than in females. Furthermore, harsher conditions, varying both in time and space (i.e., Sweden vs. France), should increase winter weight loss, and thus, mass change differences between the sexes should be stronger and show more variation in Sweden than in France.

References Blanckenhorn, W. U., Stillwell, R. C., Young, K. A., Fox, C. W., & Ashton, K. G. (2006). When Rensch meets Bergmann: does sexual size dimorphism change systematically with latitude? Evolution, 60(10), 2004-2011. https://doi.org/10.1554/06-110.1 | Body mass change over winter is consistently sex-specific across roe deer (*Capreolus capreolus*) populations | Mark Hewison, Nadège Bonnot, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Petter Kjellander, Jean-François Lemaitre, Nicolas Morellet & Maryline Pellerin | <p>In most polygynous vertebrates, males must allocate energy to growing secondary sexual characteristics, such as ornaments or weapons, that they require to attract and defend potential mates, impacting body condition and potentially entailing fi... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Life history | Denis Réale | 2022-09-16 15:41:53 | View | |

18 Sep 2024

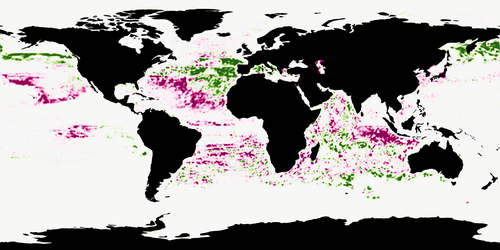

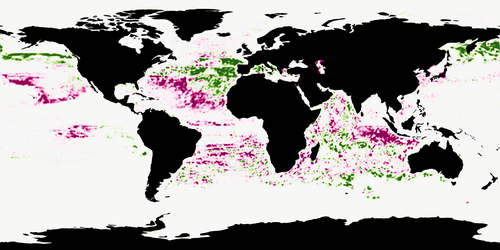

Predicting species distributions in the open ocean with convolutional neural networksGaétan Morand, Alexis Joly, Tristan Rouyer, Titouan Lorieul, Julien Barde https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.11.551418The potential of Convolutional Neural Networks for modeling species distributionsRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Jean-Olivier Irisson, Sakina-Dorothee Ayata and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-Olivier Irisson, Sakina-Dorothee Ayata and 1 anonymous reviewer

Morand et al. (2024) designed convolutional neural networks to predict the occurrences of 38 marine animals worldwide. The environmental predictors were sea surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration, salinity and fifteen others. The time of some of the predictors was chosen to be as close as possible to the time of the observed occurrence. A very interesting feature of PCI Ecology is that reviews are provided with the final manuscript and the present recommendation text. The main question debated during the review process was whether the CNN modeling approach used here can be defined as a kind of niche modeling. Another interesting point is that the CNN model is used here as a multi-species classifier, meaning that it provides the ranked probability that a given observation corresponds to one of the 38 species considered in the study, depending on the environmental conditions at the location and time of the observation. In other words, the model provides the relative chance of choosing each of the 38 species at a given time and place. Imagine that you are only studying two species that have exactly the same niche, a standard SDM approach should provide a high probability of occurrence close to 1 in localities where environmental conditions are very and equally suited to both species, while the CNN classifier would provide a value close to 0.5 for both species, meaning that we have an equal chance of choosing one or the other. Consequently, the fact that the probability given by the classifier is higher for a species at a given point than at another point does not (necessarily) mean that the first point presents better environmental conditions for that species but rather that we are more likely to choose it over one of the other species at this point than at another. In fact, the classification task also reflects whether the other 37 species are more or less likely to be found at each point. The classifier, therefore, does not provide the relative probability of occurrence of a species in space but rather a relative chance of finding it instead of one of the other 37 species at each point of space and time. Finally, CNN-based species distribution modelling is a powerful and promising tool for studying the distributions of multi-species assemblages as a function of local environmental features but also of the spatial heterogeneity of each feature around the observation point in space and time (Deneu et al. 2021). It allows acknowledging the complex effects of environmental predictors and the roles of their spatial and temporal heterogeneity through the convolution operations performed in the neural network. As more and more computationally intensive tools become available, and as more and more environmental data becomes available at finer and finer temporal and spatial scales, the CNN approach is likely to be increasingly used to study biodiversity patterns across spatial and temporal scales. References Botella, C., Joly, A., Bonnet, P., Monestiez, P., and Munoz, F. (2018). Species distribution modeling based on the automated identification of citizen observations. Applications in Plant Sciences, 6(2), e1029. https://doi.org/10.1002/aps3.1029 Deneu, B., Servajean, M., Bonnet, P., Botella, C., Munoz, F., and Joly, A. (2021). Convolutional neural networks improve species distribution modelling by capturing the spatial structure of the environment. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(4), e1008856. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008856 Morand, G., Joly, A., Rouyer, T., Lorieul, T., and Barde, J. (2024) Predicting species distributions in the open ocean with convolutional neural networks. bioRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.11.551418 Ovaskainen, O., Tikhonov, G., Norberg, A., Guillaume Blanchet, F., Duan, L., Dunson, D., ... and Abrego, N. (2017). How to make more out of community data? A conceptual framework and its implementation as models and software. Ecology letters, 20(5), 561-576. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12757 | Predicting species distributions in the open ocean with convolutional neural networks | Gaétan Morand, Alexis Joly, Tristan Rouyer, Titouan Lorieul, Julien Barde | <p>As biodiversity plummets due to anthropogenic disturbances, the conservation of oceanic species is made harder by limited knowledge of their distributions and migrations. Indeed, tracking species distributions in the open ocean is particularly ... |  | Marine ecology, Species distributions | François Munoz | Jean-Olivier Irisson | 2023-08-13 07:25:28 | View |

04 Sep 2024

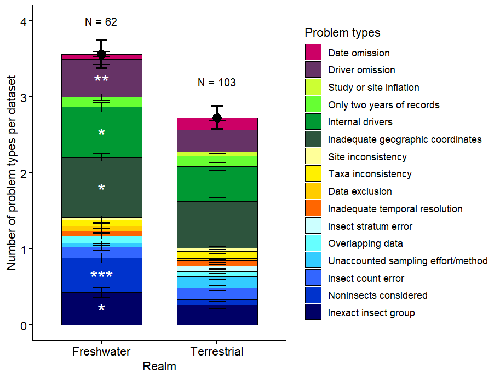

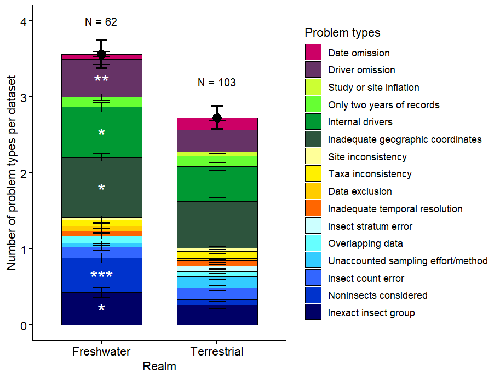

Why we need to clean the Augean stables of ecology – the case of InsectChangeRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Bradley Cardinale and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bradley Cardinale and 1 anonymous reviewer

As biodiversity has become a major global concern for a variety of stakeholders, and society in general, assessments of biodiversity trends at all spatial scales have flourished in the past decades. To assess trends, one needs data, and the more precise the data, the more precise the trend. Or, if precision is not perfect, uncertainty in the data must be acknowledged and accounted for. Such considerations have already been raised in ecology, most notably regarding the value of species distribution data to model the current and future distribution of species (Rocchini et al., 2011, Duputié et al., 2014, Tessarolo et al., 2021), leading to serious doubts regarding the value of public databases (Maldonado et al., 2015). And more recently similar issues have been raised regarding databases of species traits (Augustine et al., 2024), emphasizing the importance of good data practice and traceability. Science is by nature a self-correcting human process, with many steps of the scientific activity prone to errors and misinterpretations. Collation of ecological data, sadly, is proof of this. Spurred by the astonishing results of Hallmann et al. (2017) regarding the decline of insect biomass, and to more precisely answer the question of biodiversity trends in insects and settle an ongoing debate (Cardinale et al., 2018), van Klink et al. (2020, 2021) established the InsectChange database. Several perceptive comments have already been made regarding the possible issues in the methods and interpretations of this study (Desquilbet et al., 2020, Jähnig et al., 2021, Duchenne et al., 2022). However, the biggest issue might have been finally unearthed by Gaume & Desquilbet (2024): with poorly curated data, the InsectChange database is unlikely to support most of the initial claims regarding insect biodiversity trends. The compilation of errors and inconsistencies present in InsectChange and evinced by Gaume & Desquilbet (2024) is stunning to say the least, with a mix of field and experimental data combined without regard for experimental manipulation of environmental factors, non-standardised transformations of abundances, the use of non-insect taxa to compute insect trends, and inadequate geographical localizations of samplings. I strongly advise all colleagues interested in the study of biodiversity from global databases to consider the points raised by the authors, as it is quite likely that other databases might suffer from the same ailments as well. Reading this paper is also educating and humbling in its own way, since the publication of the original papers based on InsectChange seems to have proceeded without red flags from reviewers or editors. The need for publishing fast results that will make the next buzz, thus obeying the natural selection of bad science (Smaldino and McElreath, 2016), might be the systemic culprit. However, this might also be the opportunity ecology needs to consider the reviewing and curation of data as a crucial step of science quality assessment. To make final assessments, let us proceed with less haste. References Augustine, S. P., Bailey-Marren, I., Charton, K. T., Kiel, N. G. & Peyton, M. S. (2024) Improper data practices erode the quality of global ecological databases and impede the progress of ecological research. Global Change Biology, 30, e17116. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17116 Cardinale, B. J., Gonzalez, A., Allington, G. R. H. & Loreau, M. (2018) Is local biodiversity declining or not? A summary of the debate over analysis of species richness time trends. Biological Conservation, 219, 175-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.12.021 Desquilbet, M., Gaume, L., Grippa, M., Céréghino, R., Humbert, J.-F., Bonmatin, J.-M., Cornillon, P.-A., Maes, D., Van Dyck, H. & Goulson, D. (2020) Comment on “Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances”. Science, 370, eabd8947. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd8947 Duchenne, F., Porcher, E., Mihoub, J.-B., Loïs, G. & Fontaine, C. (2022) Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? Peer Community Journal, 2. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.131 Duputié, A., Zimmermann, N. E. & Chuine, I. (2014) Where are the wild things? Why we need better data on species distribution. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 23, 457-467. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12118 Gaume, L. & Desquilbet, M. (2024) InsectChange: Comment. biorXiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.17.545310 Hallmann, C. A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H., Stenmans, W., Müller, A., Sumser, H., Hörren, T., Goulson, D. & de Kroon, H. (2017) More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLOS ONE, 12, e0185809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185809 Jähnig, S. C., Baranov, V., Altermatt, F., Cranston, P., Friedrichs-Manthey, M., Geist, J., He, F., Heino, J., Hering, D., Hölker, F., Jourdan, J., Kalinkat, G., Kiesel, J., Leese, F., Maasri, A., Monaghan, M. T., Schäfer, R. B., Tockner, K., Tonkin, J. D. & Domisch, S. (2021) Revisiting global trends in freshwater insect biodiversity. WIREs Water, 8, e1506. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1506 Maldonado, C., Molina, C. I., Zizka, A., Persson, C., Taylor, C. M., Albán, J., Chilquillo, E., Rønsted, N. & Antonelli, A. (2015) Estimating species diversity and distribution in the era of Big Data: to what extent can we trust public databases? Global Ecology and Biogeography, 24, 973-984. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12326 Rocchini, D., Hortal, J., Lengyel, S., Lobo, J. M., Jiménez-Valverde, A., Ricotta, C., Bacaro, G. & Chiarucci, A. (2011) Accounting for uncertainty when mapping species distributions: The need for maps of ignorance. Progress in Physical Geography, 35, 211-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133311399491 Smaldino, P. E. & McElreath, R. (2016) The natural selection of bad science. Royal Society Open Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160384 Tessarolo, G., Ladle, R. J., Lobo, J. M., Rangel, T. F. & Hortal, J. (2021) Using maps of biogeographical ignorance to reveal the uncertainty in distributional data hidden in species distribution models. Ecography, 44, 1743-1755. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05793 van Klink, R., Bowler, D. E., Comay, O., Driessen, M. M., Ernest, S. K. M., Gentile, A., Gilbert, F., Gongalsky, K. B., Owen, J., Pe'er, G., Pe'er, I., Resh, V. H., Rochlin, I., Schuch, S., Swengel, A. B., Swengel, S. R., Valone, T. J., Vermeulen, R., Wepprich, T., Wiedmann, J. L. & Chase, J. M. (2021) InsectChange: a global database of temporal changes in insect and arachnid assemblages. Ecology, 102, e03354. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3354 van Klink, R., Bowler, D. E., Gongalsky, K. B., Swengel, A. B., Gentile, A. & Chase, J. M. (2020) Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances. Science, 368, 417-420. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax9931 | InsectChange: Comment | Laurence Gaume, Marion Desquilbet | <p>The InsectChange database (van Klink et al. 2021) underlying the meta-analysis by van Klink et al. (2020a) compiles worldwide time series of the abundance and biomass of invertebrates reported as insects and arachnids, as well as ecological dat... |  | Biodiversity, Climate change, Freshwater ecology, Landscape ecology, Meta-analyses, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Francois Massol | 2024-01-04 18:57:01 | View | |

29 Aug 2024

Flexible reproductive seasonality in Africa-dwelling papionins is associated with low environmental productivity and high climatic unpredictabilityJules Dezeure, Julie Dagorrette, Lugdiwine Burtschell, Shahrina Chowdhury, Dieter Lukas, Larissa Swedell, Elise Huchard https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.01.591991Reproductive flexibility shapes primate survival in a changing climate driven by environmental unpredictabilityRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

As seasonal cycles become increasingly disrupted, our understanding of the ecology and evolution of reproductive seasonality in tropical vertebrates remains limited (Bronson 2009). To predict how changes in seasonality might impact these animals, it is crucial to identify which elements of their varied reproductive patterns are connected to the equally varied patterns of rainfall seasonality (within-year fluctuations) or the significant climatic unpredictability (year-to-year variations) characteristic of the intertropical region. Dezeure et al. (2024) provide a comprehensive examination of reproductive seasonality in papionin monkeys across diverse African environments. By investigating the ecological and evolutionary determinants of reproductive timing, the authors offer novel insights into how climatic factors, particularly environmental unpredictability, shape reproductive strategies in these primates. This study stands out not only for its methodological rigour but also for its contribution to our understanding of how primates adapt their reproductive behaviours to varying environmental pressures. The findings have broad implications, particularly in the context of ongoing climate change, which is expected to increase environmental unpredictability globally. The innovative approach of this paper lies in its multifaceted examination of reproductive seasonality, which integrates data from 21 wild populations of 11 papionin species. The study employs a robust statistical framework, incorporating Bayesian phylogenetic generalised linear mixed models to control for phylogenetic relatedness among species. This methodological choice is crucial because it allows the authors to disentangle the effects of environmental variables from evolutionary history, providing a more accurate picture of how current ecological factors influence reproductive strategies. The study’s focus on environmental unpredictability as a determinant of reproductive seasonality is particularly noteworthy. While previous research has established the importance of environmental seasonality (Janson and Verdolin 2005), this paper breaks new ground by showing that the magnitude of year-to-year variation in rainfall – rather than just the seasonal distribution of rainfall – plays a critical role in determining the intensity of reproductive seasonality. This finding is supported by the significant negative correlation between reproductive seasonality and environmental unpredictability, which the authors demonstrate across multiple populations and species. The results of this study are important for several reasons. First, they challenge the traditional view that reproductive seasonality is primarily driven by within-year environmental fluctuations. By showing that inter-annual variability in rainfall is a stronger predictor of reproductive timing than intra-annual variability, the authors suggest that primates, like papionins, have evolved flexible reproductive strategies to cope with the unpredictable availability of resources. This flexibility is likely an adaptive response to the highly variable environments that many African primates inhabit, where food availability can vary dramatically not just within a year but from year to year. Second, the study highlights the role of reproductive flexibility in the evolutionary success of papionins. The authors provide compelling evidence that species within the Papio genus, for example, exhibit significant variability in reproductive timing both within and between populations. This variability suggests that these species possess a remarkable ability to adjust their reproductive strategies in response to local environmental conditions, which may have contributed to their widespread distribution across diverse habitats in Africa. This finding aligns with the work of Brockman and Schaik (2005), who argued that reproductive flexibility is a key factor in the success of primates in unpredictable environments. The study also contributes to our understanding of the evolutionary transition from seasonal to non-seasonal breeding in primates. The authors propose that the loss of strict reproductive seasonality in some papionin species may represent an adaptive shift toward greater reproductive flexibility. This shift could be driven by the need to maximise reproductive success in environments where the timing of resource peaks is difficult to predict. The authors’ findings support this hypothesis, as they show that populations living in more unpredictable environments tend to have lower reproductive seasonality. The broader implications of this study (Dezeure et al. 2024) extend beyond the specific case of papionin monkeys. The findings have relevance for the study of reproductive strategies in other long-lived, tropical mammals that face similar environmental challenges. As climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of environmental unpredictability, understanding how species have historically adapted to such conditions can provide valuable insights into their potential resilience or vulnerability to future changes. Many primate species are already facing significant threats from habitat loss, hunting, and climate change. By identifying the environmental factors that influence reproductive success, Dezeure et al. (2024) study can help inform conservation strategies aimed at protecting the most vulnerable populations. For example, conservation efforts could focus on maintaining or restoring habitat features that promote reproductive flexibility, such as access to a variety of food resources that peak at different times of the year (Chapman et al.). References Brockman D, Schaik C (2005) Seasonality in Primates: Studies of Living and Extinct Human and Non-Human Primates. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542343 Bronson FH (2009) Climate change and seasonal reproduction in mammals. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 364:3331–3340. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0140 Chapman CA, Gogarten JF, Golooba M, et al Fifty+ years of primate research illustrates complex drivers of abundance and increasing primate numbers. Am J Primatol n/a:e23577. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23577 Jules Dezeure, Julie Dagorrette, Lugdiwine Burtschell, Shahrina Chowdhury, Dieter Lukas, Larissa Swedell, Elise Huchard (2024) Flexible reproductive seasonality in Africa-dwelling papionins is associated with low environmental productivity and high climatic unpredictability. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.01.591991 Janson C, Verdolin J (2005) Seasonality of primate births in relation to climate. In: Schaik CP van, Brockman DK (eds) Seasonality in Primates: Studies of Living and Extinct Human and Non-Human Primates. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 307–350 https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542343.012 | Flexible reproductive seasonality in Africa-dwelling papionins is associated with low environmental productivity and high climatic unpredictability | Jules Dezeure, Julie Dagorrette, Lugdiwine Burtschell, Shahrina Chowdhury, Dieter Lukas, Larissa Swedell, Elise Huchard | <p style="text-align: justify;">At a time when seasonal cycles are increasingly disrupted, the ecology and evolution of reproductive seasonality in tropical vertebrates remains poorly understood. In order to predict how changes in seasonality migh... | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Zoology | Cédric Sueur | 2024-05-04 18:57:25 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Vasilis Dakos (Representative)

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle