SUEUR Cédric

- Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien, Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

- Behaviour & Ethology, Coexistence, Epidemiology, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Interaction networks, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology

- recommender

Recommendations: 4

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 4

MEWC: A user-friendly AI workflow for customised wildlife-image classification

Democratising AI for Ecology: MEWC Delivers Custom Wildlife Classification to All

Recommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Timm Haucke and 1 anonymous reviewerAlthough artificial intelligence (AI) offers a powerful solution to the bottleneck in processing camera-trap imagery, ecological researchers have long struggled with the practical application of such tools. The complexity of development, training, and deploying deep learning models remains a significant barrier for many conservationists, ecologists, and citizen scientists who lack formal training in computer science. While platforms like Wildlife Insights (Ahumada et al. 2020), MegaDetector (Beery et al. 2019), and tools such as ClassifyMe (Falzon et al. 2020) have laid critical groundwork in AI-assisted wildlife monitoring, these solutions either remain opaque, lack customisability, or are often locked behind commercial or infrastructural limitations. Others, like Sherlock (Penn et al., 2024), while powerful, are not always deployable without significant local expertise. A notable example of a more open and collaborative approach is the DeepFaune initiative, which provides a free, high-performance tool for the automatic classification of European wildlife in camera-trap images, highlighting the growing importance of locally relevant, user-friendly AI solutions developed through broad partnerships (Rigoudy et al. 2022).

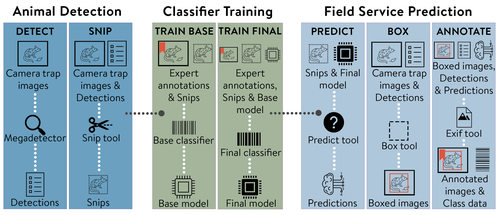

It is in this context that Brook et al. (2025) makes a compelling and timely contribution. The authors present an elegant, open-source AI pipeline—MEWC (Mega-Efficient Wildlife Classifier)—that bridges the gap between high-performance image classification and usability by non-specialists. Combining deep learning advances with user-friendly software engineering, MEWC enables users to detect, classify, and manage wildlife imagery without advanced coding skills or reliance on high-cost third-party infrastructures.

What makes MEWC particularly impactful is its modular and accessible architecture. Built on Docker containers, the system can run seamlessly across different operating systems, cloud services, and local machines. From image detection using MegaDetector to classifier training via EfficientNet or Vision Transformers, the pipeline maintains a careful balance between technical flexibility and operational simplicity. This design empowers ecologists to train their own species-specific classifiers and maintain full control over their data—an essential feature given the increasing scrutiny around data sovereignty and privacy.

The practical implications are impressive. The case study provided—focused on Tasmanian wildlife—demonstrates not only high accuracy (up to 99.6%) but also remarkable scalability, with models trainable even on mid-range desktops. Integration with community tools like Camelot (Hendry and Mann 2018)and AddaxAI (Lunteren 2023) further enhances its utility, allowing rapid expert validation and facilitating downstream analyses.

Yet the article does not shy away from discussing the limitations. As with any supervised system, MEWC’s performance is only as good as the training data provided. Class imbalances, rare species, or subtle morphological traits can challenge even the best classifiers. Moreover, the authors caution that pre-trained models may not generalise well across regions with different fauna, requiring careful curation and expert tagging for local deployments.

One particularly exciting future direction briefly mentioned—and worth highlighting—is MEWC’s potential application to behavioural and cognitive ecology (Sueur et al. 2013; Battesti et al. 2015; Grampp et al. 2019). Studies in these domains underscore the need for scalable tools to quantify social dynamics in real time. By assisting with individual identification and the detection of postures or spatial configurations, MEWC could significantly enhance the throughput, reproducibility, and objectivity of such research.

This opens the door to even richer applications. Behavioural ecologists might use MEWC for fine-grained detection tasks such as individual grooming interactions, kin proximity analysis, or identification of tool-use sequences in wild primates. Similarly, for within-species classification (e.g. sex, reproductive state, or disease symptoms), MEWC's modular backbone and compatibility with transfer learning architectures like EfficientNet or ViT make it a suitable candidate for expansion (Ferreira et al. 2020; Clapham et al. 2022).

In conclusion (Brook et al. 2025) have delivered more than a tool—they've designed an ecosystem. MEWC lowers the technical barrier to AI in ecology, promotes open science, and enables tailored workflows for a wide variety of conservation, research, and educational contexts. For anyone interested in democratising ecological AI and reclaiming control over wildlife-monitoring data, this article and its associated software are essential resources.

References

Ahumada JA, Fegraus E, Birch T, et al (2020) Wildlife Insights: A Platform to Maximize the Potential of Camera Trap and Other Passive Sensor Wildlife Data for the Planet. Environmental Conservation 47:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892919000298

Battesti M, Pasquaretta C, Moreno C, et al (2015) Ecology of information: social transmission dynamics within groups of non-social insects. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 282:20142480. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2480

Beery S, Morris D, Yang S, et al (2019) Efficient pipeline for automating species ID in new camera trap projects. Biodiversity Information Science and Standards 3:e37222. https://doi.org/10.3897/biss.3.37222

Barry W. Brook, Jessie C. Buettel, Peter van Lunteren, Prakash P. Rajmohan, R. Zach Aandahl (2025) MEWC: A user-friendly AI workflow for customised wildlife-image classification. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2ZW3D

Clapham M, Miller E, Nguyen M, Van Horn RC (2022) Multispecies facial detection for individual identification of wildlife: a case study across ursids. Mamm Biol 102:921–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42991-021-00168-5

Falzon G, Lawson C, Cheung K-W, et al (2020) ClassifyMe: A Field-Scouting Software for the Identification of Wildlife in Camera Trap Images. Animals 10:58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10010058

Ferreira AC, Silva LR, Renna F, et al (2020) Deep learning-based methods for individual recognition in small birds. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11:1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13436

Grampp M, Sueur C, van de Waal E, Botting J (2019) Social attention biases in juvenile wild vervet monkeys: implications for socialisation and social learning processes. Primates 60:261–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-019-00721-4

Hendry H, Mann C (2018) Camelot—intuitive software for camera-trap data management. Oryx 52:15–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001818

Lunteren P van (2023) AddaxAI: A no-code platform to train and deploy custom YOLOv5 object detection models. Journal of Open Source Software 8:5581. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05581

Rigoudy, N, Dussert, G, Benyoub, A et al (2023) The DeepFaune initiative: a collaborative effort towards the automatic identification of European fauna in camera trap images. Eur J Wildl Res 69, 113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-023-01742-7

Sueur C, MacIntosh AJJ, Jacobs AT, et al (2013) Predicting leadership using nutrient requirements and dominance rank of group members. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67:457–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-012-1466-5

Flexible reproductive seasonality in Africa-dwelling papionins is associated with low environmental productivity and high climatic unpredictability

Reproductive flexibility shapes primate survival in a changing climate driven by environmental unpredictability

Recommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAs seasonal cycles become increasingly disrupted, our understanding of the ecology and evolution of reproductive seasonality in tropical vertebrates remains limited (Bronson 2009). To predict how changes in seasonality might impact these animals, it is crucial to identify which elements of their varied reproductive patterns are connected to the equally varied patterns of rainfall seasonality (within-year fluctuations) or the significant climatic unpredictability (year-to-year variations) characteristic of the intertropical region.

Dezeure et al. (2024) provide a comprehensive examination of reproductive seasonality in papionin monkeys across diverse African environments. By investigating the ecological and evolutionary determinants of reproductive timing, the authors offer novel insights into how climatic factors, particularly environmental unpredictability, shape reproductive strategies in these primates. This study stands out not only for its methodological rigour but also for its contribution to our understanding of how primates adapt their reproductive behaviours to varying environmental pressures. The findings have broad implications, particularly in the context of ongoing climate change, which is expected to increase environmental unpredictability globally. The innovative approach of this paper lies in its multifaceted examination of reproductive seasonality, which integrates data from 21 wild populations of 11 papionin species. The study employs a robust statistical framework, incorporating Bayesian phylogenetic generalised linear mixed models to control for phylogenetic relatedness among species. This methodological choice is crucial because it allows the authors to disentangle the effects of environmental variables from evolutionary history, providing a more accurate picture of how current ecological factors influence reproductive strategies.

The study’s focus on environmental unpredictability as a determinant of reproductive seasonality is particularly noteworthy. While previous research has established the importance of environmental seasonality (Janson and Verdolin 2005), this paper breaks new ground by showing that the magnitude of year-to-year variation in rainfall – rather than just the seasonal distribution of rainfall – plays a critical role in determining the intensity of reproductive seasonality. This finding is supported by the significant negative correlation between reproductive seasonality and environmental unpredictability, which the authors demonstrate across multiple populations and species. The results of this study are important for several reasons. First, they challenge the traditional view that reproductive seasonality is primarily driven by within-year environmental fluctuations. By showing that inter-annual variability in rainfall is a stronger predictor of reproductive timing than intra-annual variability, the authors suggest that primates, like papionins, have evolved flexible reproductive strategies to cope with the unpredictable availability of resources. This flexibility is likely an adaptive response to the highly variable environments that many African primates inhabit, where food availability can vary dramatically not just within a year but from year to year. Second, the study highlights the role of reproductive flexibility in the evolutionary success of papionins. The authors provide compelling evidence that species within the Papio genus, for example, exhibit significant variability in reproductive timing both within and between populations. This variability suggests that these species possess a remarkable ability to adjust their reproductive strategies in response to local environmental conditions, which may have contributed to their widespread distribution across diverse habitats in Africa. This finding aligns with the work of Brockman and Schaik (2005), who argued that reproductive flexibility is a key factor in the success of primates in unpredictable environments.

The study also contributes to our understanding of the evolutionary transition from seasonal to non-seasonal breeding in primates. The authors propose that the loss of strict reproductive seasonality in some papionin species may represent an adaptive shift toward greater reproductive flexibility. This shift could be driven by the need to maximise reproductive success in environments where the timing of resource peaks is difficult to predict. The authors’ findings support this hypothesis, as they show that populations living in more unpredictable environments tend to have lower reproductive seasonality. The broader implications of this study (Dezeure et al. 2024) extend beyond the specific case of papionin monkeys. The findings have relevance for the study of reproductive strategies in other long-lived, tropical mammals that face similar environmental challenges. As climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of environmental unpredictability, understanding how species have historically adapted to such conditions can provide valuable insights into their potential resilience or vulnerability to future changes.

Many primate species are already facing significant threats from habitat loss, hunting, and climate change. By identifying the environmental factors that influence reproductive success, Dezeure et al. (2024) study can help inform conservation strategies aimed at protecting the most vulnerable populations. For example, conservation efforts could focus on maintaining or restoring habitat features that promote reproductive flexibility, such as access to a variety of food resources that peak at different times of the year (Chapman et al.).

References

Brockman D, Schaik C (2005) Seasonality in Primates: Studies of Living and Extinct Human and Non-Human Primates. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542343

Bronson FH (2009) Climate change and seasonal reproduction in mammals. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 364:3331–3340. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0140

Chapman CA, Gogarten JF, Golooba M, et al Fifty+ years of primate research illustrates complex drivers of abundance and increasing primate numbers. Am J Primatol n/a:e23577. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23577

Jules Dezeure, Julie Dagorrette, Lugdiwine Burtschell, Shahrina Chowdhury, Dieter Lukas, Larissa Swedell, Elise Huchard (2024) Flexible reproductive seasonality in Africa-dwelling papionins is associated with low environmental productivity and high climatic unpredictability. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.01.591991

Janson C, Verdolin J (2005) Seasonality of primate births in relation to climate. In: Schaik CP van, Brockman DK (eds) Seasonality in Primates: Studies of Living and Extinct Human and Non-Human Primates. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 307–350 https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542343.012

MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modelling

A deep learning model to unlock secrets of animal movement and behaviour

Recommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewerThe study of animal movement is essential for understanding their behaviour and how ecological or global changes impact their routines [1]. Recent technological advancements have improved the collection of movement data [2], but limited statistical tools have hindered the analysis of such data [3–5]. Animal movement is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by internal knowledge and memory, which are challenging to observe directly [6,7]. Routine movement behaviours and the incorporation of memory into models remain understudied.

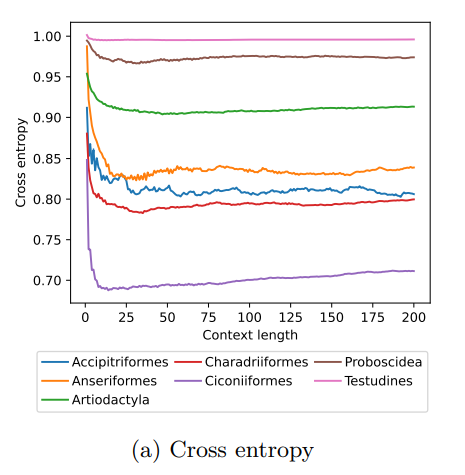

Researchers have developed ‘MoveFormer’ [8], a deep learning-based model that predicts future movements based on past context, addressing these challenges and offering insights into the importance of different context lengths and information types. The model has been applied to a dataset of over 1,550 trajectories from various species, and the authors have made the MoveFormer source code available for further research.

Inspired by the step-selection framework and efforts to quantify uncertainty in movement predictions, MoveFormer leverages deep learning, specifically the Transformer architecture, to encode trajectories and understand how past movements influence current and future ones – a critical question in movement ecology. The results indicate that integrating information from a few days to two or three weeks before the movement enhances predictions. The model also accounts for environmental predictors and offers insights into the factors influencing animal movements.

Its potential impact extends to conservation, comparative analyses, and the generalisation of uncertainty-handling methods beyond ecology, with open-source code fostering collaboration and innovation in various scientific domains. Indeed, this method could be applied to analyse other kinds of movements, such as arm movements during tool use [9], pen movements, or eye movements during drawing [10], to better understand anticipation in actions and their intentionality.

References

1. Méndez, V.; Campos, D.; Bartumeus, F. Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous Diffusion, Front Propagation and Random Searches; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-39009-8.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39010-4

2. Fehlmann, G.; King, A.J. Bio-Logging. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R830-R831.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.033

3. Jacoby, D.M.; Freeman, R. Emerging Network-Based Tools in Movement Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 301-314.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.01.011

4. Michelot, T.; Langrock, R.; Patterson, T.A. moveHMM: An R Package for the Statistical Modelling of Animal Movement Data Using Hidden Markov Models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1308-1315.

https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12578

5. Wang, G. Machine Learning for Inferring Animal Behavior from Location and Movement Data. Ecol. Inform. 2019, 49, 69-76.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2018.12.002

6. Noser, R.; Byrne, R.W. Change Point Analysis of Travel Routes Reveals Novel Insights into Foraging Strategies and Cognitive Maps of Wild Baboons. Am. J. Primatol. 2014, 76, 399-409.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22181

7. Fagan, W.F.; Lewis, M.A.; Auger‐Méthé, M.; Avgar, T.; Benhamou, S.; Breed, G.; LaDage, L.; Schlägel, U.E.; Tang, W.; Papastamatiou, Y.P. Spatial Memory and Animal Movement. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1316-1329.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12165

8. Cífka, O.; Chamaillé-Jammes, S.; Liutkus, A. MoveFormer: A Transformer-Based Model for Step-Selection Animal Movement Modelling. bioRxiv 2023, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.05.531080

9. Ardoin, T.; Sueur, C. Automatic Identification of Stone-Handling Behaviour in Japanese Macaques Using LabGym Artificial Intelligence. 2023, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30465.02402

10. Martinet, L.; Pelé, M. Drawing in Nonhuman Primates: What We Know and What Remains to Be Investigated. J. Comp. Psychol. Wash. DC 1983 2021, 135, 176-184, doi:10.1037/com0000251.

https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000251

A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis”

Does elevated parasite richness in the environment affect daily path length of animals or is it the converse? An answer bringing some new elements of discussion

Recommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn 2015, Brockmeyer et al. [1] suggested that mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) may accept additional ranging costs to avoid heavily parasitized areas. Following this paper, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] questioned this interpretation and presented other hypotheses. To summarize, whilst Brockmeyer et al. [1] proposed that elevated daily path length may be a consequence of elevated parasite richness, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] viewed it as a cause. In this current paper, Charpentier and Kappeler [3] respond to some of the criticisms by Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques and discuss the putative parsimony of the two competing scenarios. The manuscript is interesting and focuses on an important question concerning the discussion about the social organization and home range use in wild mandrills. This answer helps to move this debate forward and should stimulate more empirical studies of the role of environmentally-transmitted parasites in shaping ranging and movement patterns of wild vertebrates. Given the elements this paper brings to the topics, it should have been published in American Journal of Primatology, the journal that published the two previous articles.

References

[1] Brockmeyer, T., Kappeler, P. M., Willaume, E., Benoit, L., Mboumba, S., & Charpentier, M. J. E. (2015). Social organization and space use of a wild mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) group. American Journal of Primatology, 77(10), 1036–1048. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22439

[2] Bicca-Marques, J. C., & Calegaro-Marques, C. (2016). Ranging behavior drives parasite richness: A more parsimonious hypothesis. American Journal of Primatology, 78(9), 923–927. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22561

[3] Charpentier, M. J., & Kappeler, P. M. (2018). A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis.” ArXiv:1805.08151v2 [q-Bio]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.08151