Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban Environments

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient

Abstract

Recommendation: posted 01 March 2024, validated 01 March 2024

Diaz, A. (2024) Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban Environments. Peer Community in Ecology, 100587. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100587

Recommendation

Across the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021).

Urbanization engenders profound alterations in environmental conditions, exerting substantial impacts on biological communities. The expansion of built infrastructure, modification of land use patterns, and the introduction of impervious surfaces and habitat fragmentation are key facets of urbanization (Faeth et al. 2011). These alterations generate biodiversity loss, changes in the composition of biological communities, disruptions in access and availability of food and nutrients, and a loss of efficiency in the immune system's control of infections, etc. (Reyes et al. 2013).

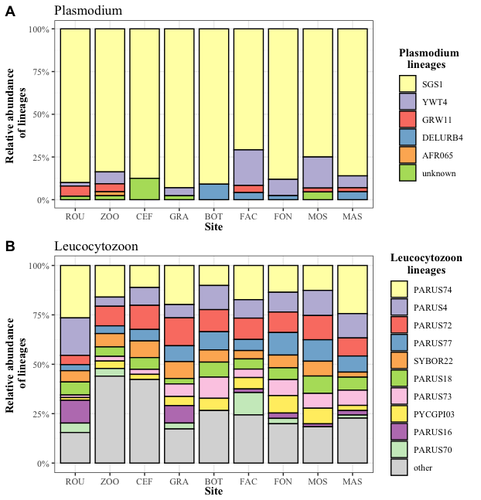

In this study, Caizergues et al. (2023) investigated the prevalence and diversity of avian malaria parasites (Plasmodium/Haemoproteus sp. and Leucocytozoon sp.) in great tits (Parus major) living across an urbanization gradient. The study reveals nuanced patterns of avian malaria prevalence and lineage diversity in great tits across urban and non-urban environments. While overall parasite diversity remains consistent, there are marked differences in prevalence between life stages and habitats. They observed a high prevalence in adult birds (from 95% to 100%), yet lower prevalence in fledglings (from 0% to 38%). Notably, urban nestlings exhibit higher parasite prevalence than their non-urban counterparts, suggesting a potential link between early malaria infection and the urban heat island effect. This finding underscores the importance of considering both spatial and temporal aspects of urbanization in understanding disease dynamics. Parasite lineages were not habitat-specific. The results suggest a potential parasitic burden in more urbanized areas, with a marginal but notable effect of nest-level urbanization on Plasmodium prevalence. This challenges the common perception of lower parasitic prevalence in urban environments and highlights the need for further investigation into the factors influencing parasite prevalence at finer spatial scales.

The discussion emphasizes the significance of examining vector distributions, abundance, and diversity in urban areas, which may be influenced by ecological niches and the presence of suitable habitats such as marshes. The identification of habitat-specific Haemosporidian lineages, particularly those occurring more frequently in urban areas, raises intriguing questions about the factors influencing parasite diversity. The presence of rare lineages in urban environments, such as AFR065, DELURB4, and YWT4, suggests a potential connection between urban bird communities and specific parasite strains.

Future research should empirically demonstrate these relationships to enhance our understanding of urban parasitology. This finding has broader implications for wildlife epidemiology, especially when introducing or keeping exotic wildlife in contact with native species. The study highlights the importance of considering not only the prevalence but also the specific lineages of parasites in understanding the dynamics of avian malaria in urban and non-urban habitats. This preprint contributes valuable insights to the ongoing discourse on the intricate interplay between ecological repercussions of human-induced changes (urbanization), biological communities, and the prevalence of vector-borne diseases.

References

Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263

Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118.

Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x

Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x

Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4

The recommender in charge of the evaluation of the article and the reviewers declared that they have no conflict of interest (as defined in the code of conduct of PCI) with the authors or with the content of the article. The authors declared that they comply with the PCI rule of having no financial conflicts of interest in relation to the content of the article.

This work was funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (grant “EVOMALWILD”, ANR-17-CE35-0012) and long-term support from the OSU-OREME (Observatoire des Sciences de l’Univers – Observatoire de REcherche Montpellierain de l’Environnement). B.R. was supported by the Betty Moore Foundation (grant GBMF9881).

Reviewed by Ana Paula Mansilla , 15 Jan 2024

, 15 Jan 2024

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 2, 31 Jan 2024

In their manuscript “Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient” Caizergues and co-authors report on the impact of urbanization on the prevalence and diversity of malaria parasites in two areas with different degree of anthropogenic disturbance, in Montpellier, France.

The manuscript is generally well-written and follow scientific convention. The introduction is nicely written and provides enough background information to support the relevance and interest of this study. Methods are also clear. Even though the results originally needed an expansion, this version provides much better information and analyses of the data obtained were deeply performed, and thus supporting the conclusions.

This will make a nice contribution to the body of literature regarding studies dealing with the urban ecology of host-parasite interactions.

In general, this is a much improved version of an earlier manuscript I revised, all my concerns were addressed, and I think it is a valuable contribution that merits publication.

https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100587.rev22Evaluation round #1

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263

Version of the preprint: 2

Author's Reply, 15 Dec 2023

Decision by Adrian Diaz, posted 06 Nov 2023, validated 06 Nov 2023

Dear authors,

Thanks so much for consider your work to be recommended by PCI Ecology.

After carefully revision of myself and based on 3 revisions from reviewers I invited you to read revisions and submitted a new reviewed version of your manuscript. As you can see, the work is important and support new and needed information about diseases ecology and land use. Most of reviewers have expressed concern on methodology and statistical analyses, specially when classified urban vs. non urban sites. This classification was quite artificial and not considered the landscape heterogenity.

Attached you will find reviewers comments.

Best wishes

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 1, 16 Oct 2023

This study is very interesting in that it investigates the impact of urbanization on host/parasite interactions beyond the usual but too simplistic « urban vs. non-urban » dichotomy. It relies on a very valuable longitudinal monitoring program of great tits and their parasites in contrasted habitats from Southern France. Although I am not a native English speaker, I have the feeling that the manuscript is well written.

To me, this work provides new insghts into urban ecology, especially urban health ecology, and it clearly deserves to be made available to a wide academic audience. However, I would like to raise a few metholodogical issues which I believe that, once addressed by the authors, may make their conclusions more robust and convincing.

The choice of the study model and the experimental design

I am not an expert about avian malaria and I obviously lack basic knowledge about it. So the following remarks may be poorly pertinent. But in case…

The authors state that the tit – Haemosporidian parasites pathosystem is accurate for exploring host/parasite interactions evolution in regards to urbanization. Although I understand that they can rely on a very valuable long-term monitoring program dedciated to this particular model, I wonder to which extent their statement is true.

(1) Indeed, by essence, vector-transmitted parasites are expected to be drastically impacted by vector(s) spatio-temporal distribution, ecology and evolution, thus adding a critical layer of eco-evolutionary processes at play (i.e., vector-environment, vector-parasite as well as vector-reservoir interactions). As a direct consequence, investigations of the relationships between habitat and parasite characteristics should be complicated by vector-associated confounding factors. In fine, convincing patterns may be retrieved only with very robust datasets (that allow one to take all major components into account), hence, most probably, very large sample sizes. In this paper, although total sample size reaches 386 birds, class-specific sample sizes may drastically drop down when one takes into account sex (N=2), age (2), sites (9) and year (N=6). For instance, this makes an average of <6 individuals (both males and females) per site and year. Yet, it may be possible that each of these factors plays an important role in the evolution of host-parasite evolution in urban vs. non-urban habitats. Could resulting sample sizes be too low to be biologically representative, and statistically sound?

(2) In addition, parasite prevalence in a given host species may be greatly influenced by the presence/absence or relative abundance of alternative host species (not even talking about alternative vector species). For this reasons, and since many readers (including me) may not be familiar with the biological models used, the authors should provide some pieces of information in the introduction about Plasmodium and Leucocytozon specificity to great tits in the studied area. Note that the presence of other (abundant) hosts, even only in some of the studied sites, would strongly weaken the study, and would deserve to be discussed in details.

(3) In the same manner, could variations in distribution and relative abundance of Haemosporidian vector species (Culex pipiens… and others?) exist, so that they may obscure urban vs. non-urban patterns retrieved here? For instance, the authors explain that massive insecticide-based control treatments were implemented against mosquitoes in this region of France (page 5, line 122-124). Were these treatments applied similarly in urban and non-urban areas? Did they impact them in similar ways in terms of mosquito and parasite ecology and population dynamics in urban and non-urban areas? If not, could the contrasted effects of insecticide-based control inside vs. outside cities explain at least partly the urban vs. non-urban patterns described here?

As a conclusion, I suggest that these potential caveats/biases/limits are addressed, and that, if realistic, they are made explicit and that the associated conclusions are softened.

Analyses

(5) Similar to the possible sample size issue raised above (see point 1), most of the Results and Discussion sections as well as the Figures deal with prevalence data, hence proportions. However, indicating raw values and sample sizes (e.g., in Figures 2, 3 and 5; in the Results section, page 17, line 334; etc) would allow the readers to better grasp how confident they can be in the interpretation of the data. Dealing with dozens of individuals when interpreting a prevalence is probably not as convincing as dealing with a one or two positive individuals out of a handsome. As it stands, the paper does not allow one to see clearly what the sample sizes are about (see point 1).

(6) Page 11, lines 255-256: the authors state that using only lineages for which type II error is below 0.2 and that occur at least 10 times ensures « statistical robustness ». Could they argue (or give a reference) about this approach?

(7) Although I understand from Figure 1 that the zoo site (ZOO) lies inside the limits of Montpellier city per se, it looks like a quite large area between two other large green spaces. In addition, the authors describe it as « the least urbanized urban site » (page 14, line 313). Could it be that this zoo display ecological features that makes it quite different from what is usually perceived as « urban » sites (or even urban parks)? Could this particular zone be more preserved (wild?) than other urban parks, a fortiori other hard-built urban sites? If yes, when performing urban vs. non-urban sites analyses, wouldn’t it be pertinent to consider ZOO as a non-urban site (or to remove it from these particular binary analyses)?

Minor and wording remarks

(8) In the introduction, when briefly describing urban habitats characteristics, the authors may want to complement their sentence about living organisms communities, and add that animal and microbial communities are also drastcially modified and usually dominated by exotic species (page 3, line 50).

(9) I am not sure about the term « vector species » as it is used in the Introduction (see e.g. page 3, line 59): do the authors mean « reservoir species », « vector and reservoir species », « host species », etc?

(10) The positive and negative impacts of urbanization on disease prevalence may not always be exclusive, and the sole dichotomic (i.e. « twofold ») perspective of urbanization / disease prevalence may be a bit simplistic. For instance, urban environment may offer larger quantities of food, but diet of lower quality, thus potentially having both positive and negative effects on hosts’ body condition, immune system, hence reproduction and fitness, competency towards parasites, etc. The authors may want to slightly modify their statement to take such a complexity into account.

(11) I am not sure to have it right: are all Plasmodium lineages more prevalent in urbanized sites (Conclusion, page 24, lines 482-483), or only the YWT4 lineage (Figure 5)?

https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100587.rev11Reviewed by Ana Paula Mansilla , 13 Oct 2023

, 13 Oct 2023

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 2, 21 Oct 2023

Dear Editor:

I do find the present Article of interest for the scientific community. The topic is interesting and well developed. The data is organized, statistical analyzes are appropriate, and the conclusion is well supported with the results obtained. I includ minor comments or suggestions within the text, which I uploaded.

Best regards,

Reviewer #

Download the review https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100587.rev13