Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Apr 2021

Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in EuropeOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dpA planned experiment on local adaptation in a host-parasite system: is adaptation to the host linked to its recent domestication?Recommended by Eric Petit based on reviews by Sharon Zytynska, Alex Stemmelen and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Sharon Zytynska, Alex Stemmelen and 1 anonymous reviewer

Local adaptation shall occur whenever selective pressures vary across space and overwhelm the effects of gene flow and local extinctions (Kawecki and Ebert 2004). Because the intimate interaction that characterizes their relationship exerts a strong selective pressure on both partners, host-parasite systems represent a classical example in which local adaptation is expected from rapidly evolving parasites adapting to more evolutionary constrained hosts (Kaltz and Shykoff 1998). Such systems indeed represent a large proportion of the study-cases in local adaptation research (Runquist et al. 2020). Biotic interactions intervene in many environment-related societal challenges, so that understanding when and how local adaptation arises is important not only for understanding evolutionary dynamics but also for more applied questions such as the control of agricultural pests, biological invasions, or pathogens (Parker and Gilbert 2004). The exact conditions under which local adaptation does occur and can be detected is however still the focus of many theoretical, methodological and empirical studies (Blanquart et al. 2013, Hargreaves et al. 2020, Hoeksema and Forde 2008, Nuismer and Gandon 2008, Richardson et al. 2014). A recent review that evaluates investigations that examined the combined influence of biotic and abiotic factors on local adaptation reaches partial conclusions about their relative importance in different contexts and underlines the many traps that one has to avoid in such studies (Runquist et al. 2020). The authors of this review emphasize that one should evaluate local adaptation using wild-collected strains or populations and over multiple generations, on environmental gradients that span natural ranges of variation for both biotic and abiotic factors, in a theory-based hypothetico-deductive framework that helps interpret the outcome of experiments. These multiple targets are not easy to reach in each local adaptation experiment given the diversity of systems in which local adaptation may occur. Improving research practices may also help better understand when and where local adaptation does occur by adding controls over p-hacking, HARKing or publication bias, which is best achieved when hypotheses, date collection and analytical procedures are known before the research begins (Chambers et al. 2014). In this regard, the route taken by Olvera-Vazquez et al. (2021) is interesting. They propose to investigate whether the rosy aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) recently adapted to its cultivated host, the apple tree (Malus domestica), and chose to pre-register their hypotheses and planned experiments on PCI Ecology (Peer Community In 2020). Though not fulfilling all criteria mentioned by Runquist et al. (2020), they clearly state five hypotheses that all relate to the local adaptation of this agricultural pest to an economically important fruit tree, and describe in details a powerful, randomized experiment, including how data will be collected and analyzed. The experimental set-up includes comparisons between three sites located along a temperature transect that also differ in local edaphic and biotic factors, and contrasts wild and domesticated apple trees that originate from the three sites and were both planted in the local, sympatric site, and transplanted to allopatric sites. Beyond enhancing our knowledge on local adaptation, this experiment will also test the general hypothesis that the rosy aphid recently adapted to Malus sp. after its domestication, a question that population genetic analyses was not able to answer (Olvera-Vazquez et al. 2020). References Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2013) A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16, 1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12150 Briscoe Runquist RD, Gorton AJ, Yoder JB, Deacon NJ, Grossman JJ, Kothari S, Lyons MP, Sheth SN, Tiffin P, Moeller DA (2019) Context Dependence of Local Adaptation to Abiotic and Biotic Environments: A Quantitative and Qualitative Synthesis. The American Naturalist, 195, 412–431. https://doi.org/10.1086/707322 Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ, Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ (2014) Instead of “playing the game” it is time to change the rules: Registered Reports at <em>AIMS Neuroscience</em> and beyond. AIMS Neuroscience, 1, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2014.1.4 Hargreaves AL, Germain RM, Bontrager M, Persi J, Angert AL (2019) Local Adaptation to Biotic Interactions: A Meta-analysis across Latitudes. The American Naturalist, 195, 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1086/707323 Hoeksema JD, Forde SE (2008) A Meta‐Analysis of Factors Affecting Local Adaptation between Interacting Species. The American Naturalist, 171, 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/527496 Kaltz O, Shykoff JA (1998) Local adaptation in host–parasite systems. Heredity, 81, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00435.x Kawecki TJ, Ebert D (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 7, 1225–1241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2008) Moving beyond Common‐Garden and Transplant Designs: Insight into the Causes of Local Adaptation in Species Interactions. The American Naturalist, 171, 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1086/587077 Olvera-Vazquez SG, Remoué C, Venon A, Rousselet A, Grandcolas O, Azrine M, Momont L, Galan M, Benoit L, David G, Alhmedi A, Beliën T, Alins G, Franck P, Haddioui A, Jacobsen SK, Andreev R, Simon S, Sigsgaard L, Guibert E, Tournant L, Gazel F, Mody K, Khachtib Y, Roman A, Ursu TM, Zakharov IA, Belcram H, Harry M, Roth M, Simon JC, Oram S, Ricard JM, Agnello A, Beers EH, Engelman J, Balti I, Salhi-Hannachi A, Zhang H, Tu H, Mottet C, Barrès B, Degrave A, Razmjou J, Giraud T, Falque M, Dapena E, Miñarro M, Jardillier L, Deschamps P, Jousselin E, Cornille A (2020) Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa. bioRxiv, 2020.12.11.421644. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644 Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. (2021) Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) to its host (Malus domestica) and to its climate in Europe. In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dp, ver. 4. Parker IM, Gilbert GS (2004) The Evolutionary Ecology of Novel Plant-Pathogen Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 675–700. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132339 Peer Community In. (2020, January 15). Submit your preregistration to Peer Community In for peer review. https://peercommunityin.org/2020/01/15/submit-your-preregistration-to-peer-community-in-for-peer-review/ Richardson JL, Urban MC, Bolnick DI, Skelly DK (2014) Microgeographic adaptation and the spatial scale of evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.002 | Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in Europe | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T.,... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Understanding the extent of local adaptation in natural populations and the mechanisms enabling populations to adapt to their environment is a major avenue in ecology research. Host-parasite interaction is widely se... | Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations | Eric Petit | 2020-07-26 18:31:42 | View | ||

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

30 Mar 2021

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesBlaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6sFrom cognition to range dynamics – and from preregistration to peer-reviewed preprintRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by Laure Cauchard and 1 anonymous reviewerIn 2018 Blaisdell and colleagues set out to study how causal cognition may impact large scale macroecological patterns, more specifically range dynamics, in the great-tailed grackle (Fronhofer 2019). This line of research is at the forefront of current thought in macroecology, a field that has started to recognize the importance of animal behaviour more generally (see e.g. Keith and Bull (2017)). Importantly, the authors were pioneering the use of preregistrations in ecology and evolution with the aim of improving the quality of academic research. Now, nearly 3 years later, it is thanks to their endeavour of making research better that we learn that the authors are “[...] unable to speculate about the potential role of causal cognition in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range.” (Blaisdell et al. 2021; page 2). Is this a success or a failure? Every reader will have to find an answer to this question individually and there will certainly be variation in these answers as becomes clear from the referees’ comments. In my opinion, this is a success story of a more stringent and transparent approach to doing research which will help us move forward, both methodologically and conceptually. References Fronhofer (2019) From cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroe- Keith, S. A. and Bull, J. W. (2017) Animal culture impacts species' capacity to realise climate-driven range shifts. Ecography, 40: 296-304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02481 Blaisdell, A., Seitz, B., Rowney, C., Folsom, M., MacPherson, M., Deffner, D., and Logan, C. J. (2021) Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles. PsyArXiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6s | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Blaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ | <p>Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geo... | Preregistrations | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-11-27 09:49:55 | View | ||

29 Mar 2021

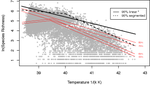

Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variationRicardo A. Segovia https://doi.org/10.1101/836338New light on the baseline importance of temperature for the origin of geographic species richness gradientsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers

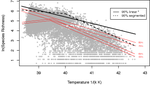

Whether environmental conditions –in particular energy and water availability– are sufficient to account for species richness gradients (e.g. Currie 1991), or the effects of other biotic and historical or regional factors need to be considered as well (e.g. Ricklefs 1987), was the subject of debate during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Francis & Currie 2003; Hawkins et al. 2003, 2006; Currie et al. 2004; Ricklefs 2004). The metabolic theory of ecology (Brown et al. 2004) provided a solid and well-rooted theoretical support for the preponderance of energy as the main driver for richness variations. As any good piece of theory, it provided testable predictions about the sign and shape (i.e. slope) of the relationship between temperature –a key aspect of ambient energy– and species richness. However, these predictions were not supported by empirical evaluations (e.g. Kreft & Jetz 2007; Algar et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 2007a), as the effects of a myriad of other environmental gradients, regional factors and evolutionary processes result in a wide variety of richness–temperature responses across different groups and regions (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Hortal et al. 2008). So, in a textbook example of how good theoretical work helps advancing science even if proves to be (partially) wrong, the evaluation of this aspect of the metabolic theory of ecology led to current understanding that, while species richness does respond to current climatic conditions, many other ecological, evolutionary and historical factors do modify such response across scales (see, e.g., Ricklefs 2008; Hawkins 2008; D’Amen et al. 2017). And the kinetic model linking mean annual temperature and species richness (Allen et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2004) was put aside as being, perhaps, another piece of the puzzle of the origin of current diversity gradients. Segovia (2021) puts together an elegant way of reinvigorating this part of the metabolic theory of ecology. He uses quantile regressions to model just the upper parts of the relationship between species richness and mean annual temperature, rather than modelling its central tendency through the classical linear regression family of methods –as was done in the past. This assumes that the baseline effect of ambient energy does produce the negative linear relationship between richness and temperature predicted by the kinetic model (Allen et al. 2002), but also that this effect only poses an upper limit for species richness, and the effects of other factors may result in lower levels of species co-occurrence, thus producing a triangular rather than linear relationship. The results of Segovia’s simple and elegant analytical design show unequivocally that the predictions of the kinetic model become progressively more explanatory towards the upper quartiles of the relationship between species richness and temperature along over 10,000 tree local inventories throughout the Americas, reaching over 70% of explanatory power for the upper 5% of the relationship (i.e. the 95% quantile). This confirms to a large extent his reformulation of the predictions of the kinetic model. Further, the neat study from Segovia (2021) also provides evidence confirming that the well-known spatial non-stationarity in the richness–temperature relationship (see Cassemiro et al. 2007) also applies to its upper-bound segment. Both the explanatory power and the slope of the relationship in the 95% upper quantile vary widely between biomes, reaching values similar to the predictions of the kinetic model only in cold temperate environments –precisely where temperature becomes more important than water availability as a constrain to plant life (O’Brien 1998; Hawkins et al. 2003). Part of these variations are indeed related with changes in water deficit and number of frost days along the XXth Century, as shown by the residuals of this paper (Segovia 2021) and a more detailed separate study (Segovia et al. 2020). This pinpoints the importance of the relative balance between water and energy as two of the main climatic factors constraining species diversity gradients, confirming the value of hypotheses that date back to Humboldt’s work (see Hawkins 2001, 2008). There is however a significant amount of unexplained variation in Segovia’s analyses, in particular in the progressive departure of the predictions of the kinetic model as we move towards the tropics, or downwards along the lower quantiles of the richness–temperature relationship. This calls for a deeper exploration of the factors that modify the baseline relationship between richness and energy, opening a new avenue for the macroecological investigation of how different forces and processes shape up geographical diversity gradients beyond the mere energetic constrains imposed by the basal limitations of multicellular life on Earth. References Algar, A.C., Kerr, J.T. and Currie, D.J. (2007) A test of Metabolic Theory as the mechanism underlying broad-scale species-richness gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 170-178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00275.x Allen, A.P., Brown, J.H. and Gillooly, J.F. (2002) Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science, 297, 1545-1548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072380 Brown, J.H., Gillooly, J.F., Allen, A.P., Savage, V.M. and West, G.B. (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology, 85, 1771-1789. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-9000 Cassemiro, F.A.d.S., Barreto, B.d.S., Rangel, T.F.L.V.B. and Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. (2007) Non-stationarity, diversity gradients and the metabolic theory of ecology. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 820-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00332.x Currie, D.J. (1991) Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist, 137, 27-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/285144 Currie, D.J., Mittelbach, G.G., Cornell, H.V., Field, R., Guegan, J.-F., Hawkins, B.A., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2004) Predictions and tests of climate-based hypotheses of broad-scale variation in taxonomic richness. Ecology Letters, 7, 1121-1134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00671.x D'Amen, M., Rahbek, C., Zimmermann, N.E. and Guisan, A. (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Francis, A.P. and Currie, D.J. (2003) A globally consistent richness-climate relationship for Angiosperms. American Naturalist, 161, 523-536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/368223 Hawkins, B.A. (2001) Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8 Hawkins, B.A. (2008) Recent progress toward understanding the global diversity gradient. IBS Newsletter, 6.1, 5-8. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr2k1dd Hawkins, B.A., Field, R., Cornell, H.V., Currie, D.J., Guégan, J.-F., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Mittelbach, G.G., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E., Porter, E.E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2003) Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology, 84, 3105-3117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8006 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Jaramillo, C.A. and Soeller, S.A. (2006) Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 770-780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01452.x Hawkins, B.A., Albuquerque, F.S., Araújo, M.B., Beck, J., Bini, L.M., Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J., Castro Parga, I., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Ferrer-Castán, D., Field, R., Gómez, J.F., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Kitching, I.J., León-Cortés, J.L., et al. (2007a) A global evaluation of metabolic theory as an explanation for terrestrial species richness gradients. Ecology, 88, 1877-1888. doi:10.1890/06-1444.1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1444.1 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Bini, L.M., Araújo, M.B., Field, R., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Rahbek, C., Rodríguez, M.Á. and Sanders, N.J. (2007b) Metabolic theory and diversity gradients: Where do we go from here? Ecology, 88, 1898–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-2141.1 Hortal, J., Rodríguez, J., Nieto-Díaz, M. and Lobo, J.M. (2008) Regional and environmental effects on the species richness of mammal assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 35, 1202–1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01850.x Kreft, H. and Jetz, W. (2007) Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104, 5925-5930. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608361104 O'Brien, E. (1998) Water-energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 379-398. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x Ricklefs, R.E. (1987) Community diversity: Relative roles of local and regional processes. Science, 235, 167-171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4785.167 Ricklefs, R.E. (2004) A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 7, 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00554.x Ricklefs, R.E. (2008) Disintegration of the ecological community. American Naturalist, 172, 741-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/593002 Segovia, R.A. (2021) Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation. bioRxiv, 836338, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/836338 Segovia, R.A., Pennington, R.T., Baker, T.R., Coelho de Souza, F., Neves, D.M., Davis, C.C., Armesto, J.J., Olivera-Filho, A.T. and Dexter, K.G. (2020) Freezing and water availability structure the evolutionary diversity of trees across the Americas. Science Advances, 6, eaaz5373. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5373 | Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation | Ricardo A. Segovia | <p>The kinetic hypothesis of biodiversity proposes that temperature is the main driver of variation in species richness, given its exponential effect on biological activity and, potentially, on rates of diversification. However, limited support fo... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Botany, Macroecology, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2019-11-10 20:56:40 | View | |

22 Mar 2021

Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore speciesBastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544Plants preserve the ghost of competition past for herbivores, but mothers don’t careRecommended by Sara Magalhães based on reviews by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-PereiraSome biological hypotheses are widely popular, so much so that we tend to forget their original lack of success. This is particularly true for hypotheses with catchy names. The ‘Ghost of competition past’ is part of the title of a paper by the great ecologist, JH Connell, one of the many losses of 2020 (Connell 1980). The hypothesis states that, even though we may not detect competition in current populations, their traits and distributions may be shaped by past competition events. Although this hypothesis has known a great success in the ecological literature, the original paper actually ends with “I will no longer be persuaded by such invoking of "the Ghost of Competition Past"”. Similarly, the hypothesis that mothers of herbivores choose host plants where their offspring will have a higher fitness was proposed by John Jaenike in 1978 (Jaenike 1978), and later coined the ‘mother knows best’ hypothesis. The hypothesis was readily questioned or dismissed: “Mother doesn't know best” (Courtney and Kibota 1990), or “Does mother know best?” (Valladares and Lawton 1991), but remains widely popular. It thus seems that catchy names (and the intuitive ideas behind them) have a heuristic value that is independent from the original persuasion in these ideas and the accumulation of evidence that followed it. The paper by Castagneryol et al. (2021) analyses the preference-performance relationship in the box tree moth (BTM) Cydalima perspectalis, after defoliation of their host plant, the box tree, by conspecifics. It thus has bearings on the two previously mentioned hypotheses. Specifically, they created an artificial population of potted box trees in a greenhouse, in which 60 trees were infested with BTM third instar larvae, whereas 61 were left uninfested. One week later, these larvae were removed and another three weeks later, they released adult BTM females and recorded their host choice by counting egg clutches laid by these females on the plants. Finally, they evaluated the effect of previously infested vs uninfested plants on BTM performance by measuring the weight of third instar larvae that had emerged from those eggs. This experimental design was adopted because BTM is a multivoltine species. When the second generation of BTM arrives, plants have been defoliated by the first generation and did not fully recover. Indeed, Castagneryol et al. (2021) found that larvae that developed on previously infested plants were much smaller than those developing on uninfested plants, and the same was true for the chrysalis that emerged from those larvae. This provides unequivocal evidence for the existence of a ghost of competition past in this system. However, the existence of this ghost still does not result in a change in the distribution of BTM, precisely because mothers do not know best: they lay as many eggs on plants previously infested than on uninfested plants. The demonstration that the previous presence of a competitor affects the performance of this herbivore species confirms that ghosts exist. However, whether this entails that previous (interspecific) competition shapes species distributions, as originally meant, remains an open question. Species phenology may play an important role in exposing organisms to the ghost, as this time-lagged competition may have been often overlooked. It is also relevant to try to understand why mothers don’t care in this, and other systems. One possibility is that they will have few opportunities to effectively choose in the real world, due to limited dispersal or to all plants being previously infested. References Castagneyrol, B., Halder, I. van, Kadiri, Y., Schillé, L. and Jactel, H. (2021) Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.228544, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544 Connell, J. H. (1980). Diversity and the coevolution of competitors, or the ghost of competition past. Oikos, 131-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 Courtney, S. P. and Kibota, T. T. (1990) in Insect-plant interactions (ed. Bernays, E.A.) 285-330. Jaenike, J. (1978). On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects. Theoretical population biology, 14(3), 350-356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6 Valladares, G., and Lawton, J. H. (1991). Host-plant selection in the holly leaf-miner: does mother know best?. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 227-240. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/5456

| Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species | Bastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel | <p>Conspecific insect herbivores co-occurring on the same host plant interact both directly through interference competition and indirectly through exploitative competition, plant-mediated interactions and enemy-mediated interactions. However, the... |  | Competition, Herbivory, Zoology | Sara Magalhães | 2020-08-03 15:50:23 | View | |

17 Mar 2021

Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslandsCatherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137Resolving herbivore influences under climate variabilityRecommended by Jennifer Krumins based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersWe know that herbivory can have profound influences on plant communities with respect to their distribution and productivity (recently reviewed by Jia et al. 2018). However, the degree to which these effects are realized belowground in the rhizosphere is far less understood. Indeed, many independent studies and synthesis find that the environmental context can be more important than the direct effects of herbivore activity and its removal of plant biomass (Andriuzzi and Wall 2017, Schrama et al. 2013). In spite of dedicated attention, generalizable conclusions remain a bit elusive (Sitters and Venterink 2015). Picon-Cochard and colleagues (2021) help address this research conundrum in an elegant analysis that demonstrates the interaction between long-term cattle grazing and climatic variability on primary production aboveground and belowground. Over the course of two years, Picon-Cochard et al. (2021) measured above and belowground net primary productivity in French grasslands that had been subject to ten years of managed cattle grazing. When they compared these data with climatic trends, they find an interesting interaction among grazing intensity and climatic factors influencing plant growth. In short, and as expected, plants allocate more resources to root growth in dry years and more to above ground biomass in wet and cooler years. However, this study reveals the degree to which this is affected by cattle grazing. Grazed grasslands support warmer and dryer soils creating feedback that further and significantly promotes root growth over green biomass production. The implications of this work to understanding the capacity of grassland soils to store carbon is profound. This study addresses one brief moment in time of the long trajectory of this grazed ecosystem. The legacy of grazing does not appear to influence soil ecosystem functioning with respect to root growth except within the environmental context, in this case, climate. This supports the notion that long-term research in animal husbandry and grazing effects on landscapes is deeded. It is my hope that this study is one of many that can be used to synthesize many different data sets and build a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of grazing and herd management within the context of a changing climate. Herbivory has a profound influence upon ecosystem health and the distribution of plant communities (Speed and Austrheim 2017), global carbon storage (Chen and Frank 2020) and nutrient cycling (Sitters et al. 2020). The analysis and results presented by Picon-Cochard (2021) help to resolve the mechanisms that underly these complex effects and ultimately make projections for the future. References Andriuzzi WS, Wall DH. 2017. Responses of belowground communities to large aboveground herbivores: Meta‐analysis reveals biome‐dependent patterns and critical research gaps. Global Change Biology 23:3857-3868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13675 Chen J, Frank DA. 2020. Herbivores stimulate respiration from labile and recalcitrant soil carbon pools in grasslands of Yellowstone National Park. Land Degradation & Development 31:2620-2634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3656 Jia S, Wang X, Yuan Z, Lin F, Ye J, Hao Z, Luskin MS. 2018. Global signal of top-down control of terrestrial plant communities by herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6237-6242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707984115 Picon-Cochard C, Vassal N, Martin R, Herfurth D, Note P, Louault F. 2021. Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands. bioRxiv, 2020.08.23.263137, version 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137 Schrama M, Veen GC, Bakker EL, Ruifrok JL, Bakker JP, Olff H. 2013. An integrated perspective to explain nitrogen mineralization in grazed ecosystems. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15:32-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2012.12.001 Sitters J, Venterink HO. 2015. The need for a novel integrative theory on feedbacks between herbivores, plants and soil nutrient cycling. Plant and Soil 396:421-426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2679-y Sitters J, Wubs EJ, Bakker ES, Crowther TW, Adler PB, Bagchi S, Bakker JD, Biederman L, Borer ET, Cleland EE. 2020. Nutrient availability controls the impact of mammalian herbivores on soil carbon and nitrogen pools in grasslands. Global Change Biology 26:2060-2071. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15023 Speed JD, Austrheim G. 2017. The importance of herbivore density and management as determinants of the distribution of rare plant species. Biological Conservation 205:77-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.030 | Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands | Catherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault | <p>Background and Aims: Understanding how direct and indirect changes in climatic conditions, management, and species composition affect root production and root traits is of prime importance for the delivery of carbon sequestration services of gr... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning | Jennifer Krumins | 2020-08-30 19:27:30 | View | |

13 Mar 2021

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalSevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6behDispersal: from “neutral” to a state- and context-dependent viewRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTraditionally, dispersal has often been seen as “random” or “neutral” as Lowe & McPeek (2014) have put it. This simplistic view is likely due to dispersal being intrinsically difficult to measure empirically as well as “random” dispersal being a convenient simplifying assumption in theoretical work. Clobert et al. (2009), and many others, have highlighted how misleading this assumption is. Rather, dispersal seems to be usually a complex reaction norm, depending both on internal as well as external factors. One such internal factor is the sex of the dispersing individual. A recent review of the theoretical literature (Li & Kokko 2019) shows that while ideas explaining sex-biased dispersal go back over 40 years this state-dependency of dispersal is far from comprehensively understood. Sevchik et al. (2021) tackle this challenge empirically in a bird species, the great-tailed grackle. In contrast to most bird species, where females disperse more than males, the authors report genetic evidence indicating male-biased dispersal. The authors argue that this difference can be explained by the great-tailed grackle’s social and mating-system. Dispersal is a central life-history trait (Bonte & Dahirel 2017) with major consequences for ecological and evolutionary processes and patterns. Therefore, studies like Sevchik et al. (2021) are valuable contributions for advancing our understanding of spatial ecology and evolution. Importantly, Sevchik et al. also lead to way to a more open and reproducible science of ecology and evolution. The authors are among the pioneers of preregistering research in their field and their way of doing research should serve as a model for others. References Bonte, D. & Dahirel, M. (2017) Dispersal: a central and independent trait in life history. Oikos 126: 472-479. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03801 Clobert, J., Le Galliard, J. F., Cote, J., Meylan, S. & Massot, M. (2009) Informed dispersal, heterogeneity in animal dispersal syndromes and the dynamics of spatially structured populations. Ecol. Lett.: 12, 197-209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01267.x Li, X.-Y. & Kokko, H. (2019) Sex-biased dispersal: a review of the theory. Biol. Rev. 94: 721-736. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12475 Lowe, W. H. & McPeek, M. A. (2014) Is dispersal neutral? Trends Ecol. Evol. 29: 444-450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.05.009 Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. & Lukas, D. (2021) Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. EcoEvoRxiv, osf.io/t6beh, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6beh | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D | <p>In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain closer to the place they hatched for their entire lives. Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have focused on the resource-defense ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-08-24 17:53:06 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

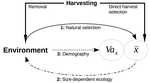

Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheriesEric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905“Hidden” natural selection and the evolution of body size in harvested stocksRecommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are exploiting biological resources since thousands of years. Exploitation of biological resources has become particularly intense since the beginning of the 20th century and the steep increase in the worldwide human population size. Marine and freshwater fishes are not exception to that rule, and they have been (and continue to be) strongly harvested as a source of proteins for humans. For some species, fishery has been so intense that natural stocks have virtually collapsed in only a few decades. The worst example begin that of the Northwest Atlantic cod that has declined by more than 95% of its historical biomasses in only 20-30 years of intensive exploitation (Frank et al. 2005). These rapid and steep changes in biomasses have huge impacts on the entire ecosystems since species targeted by fisheries are often at the top of trophic chains (Frank et al. 2005). Beyond demographic impacts, fisheries also have evolutionary impacts on populations, which can also indirectly alter ecosystems (Uusi-Heikkilä et al. 2015; Palkovacs et al. 2018). Fishermen generally focus on the largest specimens, and hence exert a strong selective pressure against these largest fish (which is called “harvest selection”). There is now ample evidence that harvest selection can lead to rapid evolutionary changes in natural populations toward small individuals (Kuparinen & Festa-Bianchet 2017). These evolutionary changes are of course undesirable from a human perspective, and have attracted many scientific questions. Nonetheless, the consequence of harvest selection is not always observable in natural populations, and there are cases in which no phenotypic change (or on the contrary an increase in mean body size) has been observed after intense harvest pressures. In a conceptual Essay, Edeline and Loeuille (Edeline & Loeuille 2020) propose novel ideas to explain why the evolutionary consequences of harvest selection can be so diverse, and how a cross talk between ecological and evolutionary dynamics can explain patterns observed in natural stocks. The general and novel concept proposed by Edeline and Loeuille is actually as old as Darwin’s book; The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It is based on the simple idea that natural selection acting on harvested populations can actually be strong, and counter-balance (or on the contrary reinforce) the evolutionary consequence of harvest selection. Although simple, the idea that natural and harvest selection are jointly shaping contemporary evolution of exploited populations lead to various and sometimes complex scenarios that can (i) explain unresolved empirical patterns and (ii) refine predictions regarding the long-term viability of exploited populations. The Edeline and Loeuille’s crafty inspiration is that natural selection acting on exploited populations is itself an indirect consequence of harvest (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). They suggest that, by modifying the size structure of populations (a key parameter for ecological interactions), harvest indirectly alters interactions between populations and their biotic environment through competition and predation, which changes the ecological theatre and hence the selective pressures acting back to populations. They named this process “size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedback loops” and develop several scenarios in which these feedback loops ultimately deviate the evolutionary outcome of harvest selection from expectation. The scenarios they explore are based on strong theoretical knowledge, and range from simple ones in which a single species (the harvest species) is evolving to more complex (and realistic) ones in which multiple (e.g. the harvest species and its prey) species are co-evolving. I will not come into the details of each scenario here, and I will let the readers (re-)discovering the complex beauty of biological life and natural selection. Nonetheless, I will emphasize the importance of considering these eco-evolutionary processes altogether to fully grasp the response of exploited populations. Edeline and Loeuille convincingly demonstrate that reduced body size due to harvest selection is obviously not the only response of exploited fish populations when natural selection is jointly considered (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). On the contrary, they show that –under some realistic ecological circumstances relaxing exploitative competition due to reduced population densities- natural selection can act antagonistically, and hence favour stable body size in exploited populations. Although this seems further desirable from a human perspective than a downsizing of exploited populations, it is actually mere window dressing as Edeline and Loeuille further showed that this response is accompanied by an erosion of the evolvability –and hence a lowest probability of long-term persistence- of these exploited populations. Humans, by exploiting biological resources, are breaking the relative equilibrium of complex entities, and the response of populations to this disturbance is itself often complex and heterogeneous. In this Essay, Edeline and Loeuille provide –under simple terms- the theoretical and conceptual bases required to improve predictions regarding the evolutionary responses of natural populations to exploitation by humans (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). An important next step will be to generate data and methods allowing confronting the empirical reality to these novel concepts (e.g. (Monk et al. 2021), so as to identify the most likely evolutionary scenarios sustaining biological responses of exploited populations, and hence to set the best management plans for the long-term sustainability of these populations. References Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. John Murray, London. Edeline, E. & Loeuille, N. (2021) Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries. bioRxiv, 2020.04.03.022905, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905 Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J. S. & Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem. Science, 308, 1621–1623. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113075 Kuparinen, A. & Festa-Bianchet, M. (2017). Harvest-induced evolution: insights from aquatic and terrestrial systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 372, 20160036. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0036 Monk, C.T., Bekkevold, D., Klefoth, T., Pagel, T., Palmer, M. & Arlinghaus, R. (2021). The battle between harvest and natural selection creates small and shy fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2009451118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009451118 Palkovacs, E.P., Moritsch, M.M., Contolini, G.M. & Pelletier, F. (2018). Ecology of harvest-driven trait changes and implications for ecosystem management. Front. Ecol. Environ., 16, 20–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1743 Uusi-Heikkilä, S., Whiteley, A.R., Kuparinen, A., Matsumura, S., Venturelli, P.A., Wolter, C., et al. (2015). The evolutionary legacy of size-selective harvesting extends from genes to populations. Evol. Appl., 8, 597–620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12268 | Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries | Eric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Harvesting may drive body downsizing along with population declines and decreased harvesting yields. These changes are commonly construed as direct consequences of harvest selection, where small-bodied, early-reproducing individuals are immedia... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Competition, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Food webs, Interaction networks, Life history, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2020-04-03 16:14:05 | View | |

14 Jan 2021

Consistent variations in personality traits and their potential for genetic improvement of biocontrol agents: Trichogramma evanescens as a case studySilène Lartigue, Myriam Yalaoui, Jean Belliard, Claire Caravel, Louise Jeandroz, Géraldine Groussier, Vincent Calcagno, Philippe Louâpre, François-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Thibaut Malausa and Jérôme Moreau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.257881Tell us how you can be, and we’ll make you better: exploiting genetic variability in personality traits to improve top-down control of agricultural pestsRecommended by Marta Montserrat based on reviews by Bart A Pannebakker, François Dumont, Joshua Patrick Byrne and Ana Pimenta Goncalves PereiraAgriculture in the XXI century faces the huge challenge of having to provide food to a rapidly growing human population, which is expected to reach 10.9 billion in 2100 (UUNN 2019), by means of practices and methods that guarantee crop sustainability, human health safety, and respect to the environment (UUNN 2015). Such regulation by the United Nations ultimately entails that agricultural scientists are urged to design strategies and methods that effectively minimize the use of harmful chemical products to control pest populations and to improve soil quality. References Bielza, P., Balanza, V., Cifuentes, D. and Mendoza, J. E. (2020). Challenges facing arthropod biological control: Identifying traits for genetic improvement of predators in protected crops. Pest Manag Sci. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5857 | Consistent variations in personality traits and their potential for genetic improvement of biocontrol agents: Trichogramma evanescens as a case study | Silène Lartigue, Myriam Yalaoui, Jean Belliard, Claire Caravel, Louise Jeandroz, Géraldine Groussier, Vincent Calcagno, Philippe Louâpre, François-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Thibaut Malausa and Jérôme Moreau | <p>Improvements in the biological control of agricultural pests require improvements in the phenotyping methods used by practitioners to select efficient biological control agent (BCA) populations in industrial rearing or field conditions. Consist... | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biological control, Evolutionary ecology, Life history | Marta Montserrat | 2020-08-24 10:40:03 | View | ||

06 Jan 2021

Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech populationCathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio https://doi.org/10.1101/645747The complexity of predicting mortality in treesRecommended by Lucía DeSoto based on reviews by Lisa Hülsmann and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the main issues of forest ecosystems is rising tree mortality as a result of extreme weather events (Franklin et al., 1987). Eventually, tree mortality reduces forest biomass (Allen et al., 2010), although its effect on forest ecosystem fluxes seems not lasting too long (Anderegg et al., 2016). This controversy about the negative consequences of tree mortality is joined to the debate about the drivers triggering and the mechanisms accelerating tree decline. For instance, there is still room for discussion about carbon starvation or hydraulic failure determining the decay processes (Sevanto et al., 2014) or about the importance of mortality sources (Reichstein et al., 2013). Therefore, understanding and predicting tree mortality has become one of the challenges for forest ecologists in the last decade, doubling the rate of articles published on the topic (*). Although predicting the responses of ecosystems to environmental change based on the traits of species may seem a simplistic conception of ecosystem functioning (Sutherland et al., 2013), identifying those traits that are involved in the proneness of a tree to die would help to predict how forests will respond to climate threatens. (*) Number (and percentage) of articles found in Web of Sciences after searching (December the 10th, 2020) “tree mortality”: from 163 (0.006%) in 2010 to 412 (0.013%) in 2020. References Allen et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest ecology and management, 259(4), 660-684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001 | Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech population | Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio | <p>Since several studies have been reporting an increase in the decline of forests, a major issue in ecology is to better understand and predict tree mortality. The interactions between the different factors and the physiological processes giving ... |  | Climate change, Physiology, Population ecology | Lucía DeSoto | 2019-05-24 11:37:38 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Vasilis Dakos (Representative)

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle