BLANCHET Simon

- Station d'Ecologie Théorique et Expérimentale, CNRS, Moulis, France

- Biodiversity, Biological invasions, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Ecosystem functioning, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact, Macroecology, Meta-analyses, Molecular ecology, Parasitology, Phenotypic plasticity, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Statistical ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 2

Reviews: 2

Recommendations: 2

Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries

“Hidden” natural selection and the evolution of body size in harvested stocks

Recommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are exploiting biological resources since thousands of years. Exploitation of biological resources has become particularly intense since the beginning of the 20th century and the steep increase in the worldwide human population size. Marine and freshwater fishes are not exception to that rule, and they have been (and continue to be) strongly harvested as a source of proteins for humans. For some species, fishery has been so intense that natural stocks have virtually collapsed in only a few decades. The worst example begin that of the Northwest Atlantic cod that has declined by more than 95% of its historical biomasses in only 20-30 years of intensive exploitation (Frank et al. 2005). These rapid and steep changes in biomasses have huge impacts on the entire ecosystems since species targeted by fisheries are often at the top of trophic chains (Frank et al. 2005).

Beyond demographic impacts, fisheries also have evolutionary impacts on populations, which can also indirectly alter ecosystems (Uusi-Heikkilä et al. 2015; Palkovacs et al. 2018). Fishermen generally focus on the largest specimens, and hence exert a strong selective pressure against these largest fish (which is called “harvest selection”). There is now ample evidence that harvest selection can lead to rapid evolutionary changes in natural populations toward small individuals (Kuparinen & Festa-Bianchet 2017). These evolutionary changes are of course undesirable from a human perspective, and have attracted many scientific questions. Nonetheless, the consequence of harvest selection is not always observable in natural populations, and there are cases in which no phenotypic change (or on the contrary an increase in mean body size) has been observed after intense harvest pressures. In a conceptual Essay, Edeline and Loeuille (Edeline & Loeuille 2020) propose novel ideas to explain why the evolutionary consequences of harvest selection can be so diverse, and how a cross talk between ecological and evolutionary dynamics can explain patterns observed in natural stocks.

The general and novel concept proposed by Edeline and Loeuille is actually as old as Darwin’s book; The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It is based on the simple idea that natural selection acting on harvested populations can actually be strong, and counter-balance (or on the contrary reinforce) the evolutionary consequence of harvest selection. Although simple, the idea that natural and harvest selection are jointly shaping contemporary evolution of exploited populations lead to various and sometimes complex scenarios that can (i) explain unresolved empirical patterns and (ii) refine predictions regarding the long-term viability of exploited populations.

The Edeline and Loeuille’s crafty inspiration is that natural selection acting on exploited populations is itself an indirect consequence of harvest (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). They suggest that, by modifying the size structure of populations (a key parameter for ecological interactions), harvest indirectly alters interactions between populations and their biotic environment through competition and predation, which changes the ecological theatre and hence the selective pressures acting back to populations. They named this process “size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedback loops” and develop several scenarios in which these feedback loops ultimately deviate the evolutionary outcome of harvest selection from expectation. The scenarios they explore are based on strong theoretical knowledge, and range from simple ones in which a single species (the harvest species) is evolving to more complex (and realistic) ones in which multiple (e.g. the harvest species and its prey) species are co-evolving.

I will not come into the details of each scenario here, and I will let the readers (re-)discovering the complex beauty of biological life and natural selection. Nonetheless, I will emphasize the importance of considering these eco-evolutionary processes altogether to fully grasp the response of exploited populations. Edeline and Loeuille convincingly demonstrate that reduced body size due to harvest selection is obviously not the only response of exploited fish populations when natural selection is jointly considered (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). On the contrary, they show that –under some realistic ecological circumstances relaxing exploitative competition due to reduced population densities- natural selection can act antagonistically, and hence favour stable body size in exploited populations. Although this seems further desirable from a human perspective than a downsizing of exploited populations, it is actually mere window dressing as Edeline and Loeuille further showed that this response is accompanied by an erosion of the evolvability –and hence a lowest probability of long-term persistence- of these exploited populations.

Humans, by exploiting biological resources, are breaking the relative equilibrium of complex entities, and the response of populations to this disturbance is itself often complex and heterogeneous. In this Essay, Edeline and Loeuille provide –under simple terms- the theoretical and conceptual bases required to improve predictions regarding the evolutionary responses of natural populations to exploitation by humans (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). An important next step will be to generate data and methods allowing confronting the empirical reality to these novel concepts (e.g. (Monk et al. 2021), so as to identify the most likely evolutionary scenarios sustaining biological responses of exploited populations, and hence to set the best management plans for the long-term sustainability of these populations.

References

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. John Murray, London.

Edeline, E. & Loeuille, N. (2021) Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries. bioRxiv, 2020.04.03.022905, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905

Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J. S. & Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem. Science, 308, 1621–1623. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113075

Kuparinen, A. & Festa-Bianchet, M. (2017). Harvest-induced evolution: insights from aquatic and terrestrial systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 372, 20160036. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0036

Monk, C.T., Bekkevold, D., Klefoth, T., Pagel, T., Palmer, M. & Arlinghaus, R. (2021). The battle between harvest and natural selection creates small and shy fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2009451118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009451118

Palkovacs, E.P., Moritsch, M.M., Contolini, G.M. & Pelletier, F. (2018). Ecology of harvest-driven trait changes and implications for ecosystem management. Front. Ecol. Environ., 16, 20–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1743

Uusi-Heikkilä, S., Whiteley, A.R., Kuparinen, A., Matsumura, S., Venturelli, P.A., Wolter, C., et al. (2015). The evolutionary legacy of size-selective harvesting extends from genes to populations. Evol. Appl., 8, 597–620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12268

Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal

Are all the roads leading to Rome?

Recommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth and 1 anonymous reviewerIdentifying the factors which favour the establishment and spread of non-native species in novel environments is one of the keys to predict - and hence prevent or control - biological invasions. This includes biological factors (i.e. factors associated with the invasive species themselves), and one of the prevailing hypotheses is that some species traits may explain their impressive success to establish and spread in novel environments [1]. In animals, most research studies have focused on traits associated with fecundity, age at maturity, level of affiliation to humans or dispersal ability for instance. The “composite picture” of the perfect (i.e. successful) invader that has gradually emerged is a small-bodied animal strongly affiliated to human activities with high fecundity, high dispersal ability and a super high level of plasticity. Of course, the story is not that simple, and actually a perfect invader sometimes – if not often- takes another form… Carrying on to identify what makes a species a successful invader or not is hence still an important research axis with major implications.

In this manuscript, Charbonnel and collaborators [2] provide an interesting opportunity to gain novel insights into our understanding of (the) traits underlying invasion success. They nicely combine the power of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) with a clever comparative approach of two closely-related invasive rodents (the house mouse Mus musculus and the black rat Rattus rattus) in a common environment. They use this experimental design to test the appealing hypothesis that pathogens may be actors of the story, and may indirectly explain why some non-native species are so successful in invading novel habitats.

It is generally assumed that the community of pathogens encountered by non-native species in novel environments is different from that of their native area. On the one hand (the enemy-release hypothesis), it can be hypothesized that non-native species, when they arrive into a novel environment, will be relaxed from the pressure imposed by their native pathogens because local pathogens are not adapted (and hence do not infect) to this novel host. Because immune defence against pathogens is highly costly, non-native species establishing into a novel environment could hence reallocate these costs to other functions such as fecundity or dispersal apparatus. This scenario has been termed the “evolution of increased competitive ability” (EICA) hypothesis [3]. On the other hand (the EICA-refined hypothesis [4]), one can assume that invaders will encounter new pathogens in newly established areas, and will allocate energy toward cost-effective immune pathways to permit allocating a non-negligible amount of energy toward other functions. Finally, a last hypothesis (the “immune protection” hypothesis) assumes major changes in pathogen composition between native and invaded areas, which should lead to an overall increase in immune investment by the native species to successfully invade novel environments [4]. This last hypothesis suggests that only non-native species being able to take up the associated costs of immunity will be successful invaders.

The role of immunity in invasion success has yet been poorly investigated, mainly because of the difficulty to simultaneously analyse multiple immune pathways [4]. Charbonnel and collaborators [2] overpass this difficulty by screening all genes expressed (using a whole RNA sequencing approach) in an immune tissue: the spleen. They do so along the invasion routes of two sympatric invasive rodents in Africa and compare anciently and newly invaded areas (respectively). For one of the two species (the house mouse), they found a high number of immune-related genes to be up-regulated in newly invaded areas compared to anciently invaded areas. All categories of immune pathways (costly and cost-effective) were up-regulated, suggesting an overall increase in immune investment in the mouse, which corroborates the “immune protection” hypothesis. For the black rat, patterns of gene expression were somewhat different, with much less pronounced differentiation in gene expression between newly and anciently invaded areas. Among the few differentiated genes, a few were associated to immune responses and some of theses genes were even down-regulated in the newly invaded areas. This pattern may actually corroborate the EICA hypothesis, although it could alternatively suggest that stochastic processes (drift) associated to recent decrease in population size (which is expected during a colonisation event) are more important than selection imposed by pathogens in shaping patterns of immune gene expression.

Overall, this study [2] suggests (i) that immune-related traits are important in predicting invasion success and (ii) that two successful species with a similar invasion history and living in similar environments can use different life-history strategies to reach the same success. This later finding is particularly relevant and intriguing as it suggests that the traits and strategies deployed by species to colonise new habitats might actually be idiosyncratic, and that, if general trends actually emerge in regards of traits predicting the success of invaders, the devil might actually be into the details. Comparative studies are extremely important to identify the general rules and the specificities sustaining actual patterns, but these approaches are yet poorly used in biological invasions (at least empirically). The work presented by Charbonnel and colleagues [2] calls for future comparative studies performed at multiple spatial scales (native vs. non-native areas, anciently vs. recently invaded areas), multiple taxonomic resolutions and across multiple traits (to search for trade-offs), so that the success of invasive species can be properly understood and predicted.

References

[1] Jeschke, J. M., & Strayer, D. L. (2006). Determinants of vertebrate invasion success in Europe and North America. Global Change Biology, 12(9), 1608-1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01213.x

[2] Blossey, B., & Notzold, R. (1995). Evolution of increased competitive ability in invasive nonindigenous plants: a hypothesis. Journal of Ecology, 83(5), 887-889. doi: 10.2307/2261425

[3] Charbonnel, N., Galan, M., Tatard, C., Loiseau, A., Diagne, C. A., Dalecky, A., Parrinello, H., Rialle, S., Severac, D., & Brouat, C. (2019). Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal. bioRxiv, 442160, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/442160

[4] Lee, K. A., & Klasing, K. C. (2004). A role for immunology in invasion biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19(10), 523-529. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.012

Reviews: 2

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis

Marking invertebrates using RFID tags

Recommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewerGuiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically.

The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it.

References

Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013

Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008.

Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695

Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082

Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900

Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure

Two paradigms for intraspecific variability

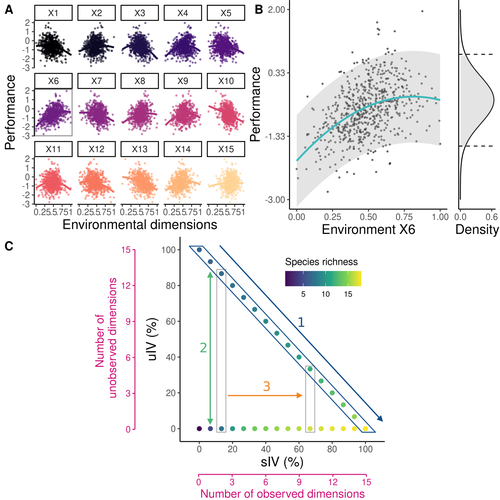

Recommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart HaegemanCommunity ecology usually concerns itself with understanding the causes and consequences of diversity at a given taxonomic resolution, most classically at the species level. Yet there is no doubt that diversity exists at all scales, and phenotypic variability within a taxon can be comparable to differences between taxa, as observed from bacteria to fish and trees. The question that motivates an active and growing body of work (e.g. Raffard et al 2019) is not so much whether intraspecific variability matters, but what we get wrong by ignoring it and how to incorporate it into our understanding of communities. There is no established way to think about diversity at multiple nested taxonomic levels, and it is tempting to summarize intraspecific variability simply by measuring species mean and variance in any trait and metric.

In this study, Girard-Tercieux et al (2023a) propose that, to understand its impact on community-level outcomes and in particular on species coexistence, we should carefully distinguish between two ways of thinking about intraspecific variability:

-"unstructured" variation, where every individual's features are like an independent random draw from a species-specific distribution, for instance, due to genetic lottery and developmental accidents

-"structured" variation that is due to each individual encountering a different but enduring microenvironment.

The latter type of variability may still appear complex and random-like when the environment is high-dimensional (i.e. multifaceted, with many different factors contributing to each individual's performance and development). Thus, it is not necessarily "structured" in the sense of being easily understood -- we may need to measure more aspects of the environment than is practical if we want to fully predict these variations.

What distinguishes this "structured" variability is that it is, in a loose sense, inheritable: individuals from the same species that grow in the same microenvironment will have the same performance, in a repeatable fashion. Thus, if each species is best at exploiting at least a fraction of environmental conditions, it is likely to avoid extinction by competition, except in the unlucky case of no propagule reaching any of the favorable sites.

By contrast, drawing each individual's preferences and performance randomly at each generation (from its own species distribution, but independently from other and past individuals) leads to stochastic dynamics, so-called ecological drift, that easily induce a large number of species extinctions.

The core intuition, that the complex spatial structure and high-dimensional nature of the environment plays a key explanatory role in species coexistence, is a running thread through several of the authors' work (e.g. Clark et al 2010), clearly inspired by their focus on tropical forests. This study, by tackling the question of intraspecific determinants of interspecific outcomes, makes a compelling addition to this line of investigation, coming as a theoretical companion to a more data-oriented study (Girard-Tercieux et al 2023b). But I believe it raises a question that is even broader in scope.

This kind of intraspecific variability, due to different individuals growing in different microenvironments, is perhaps most relevant for trees and other sessile organisms, but the distinction made here between "unstructured" and "structured" variability can likely be extended to many other ecological settings.

In my understanding, what matters most in "structured" variability is not so much it stemming from a fixed environment, but rather it being maintained across generations, rather than possibly lost by drift. This difference between variability in the form of "frozen" randomness and in the form of stochastic drift over time is highly relevant in other theoretical fields (e.g. in physics, where it is the difference between a disordered solid and a liquid), and thus, I expect that it is a meaningful distinction to make throughout community ecology.

References

James S. Clark, David Bell, Chengjin Chu, Benoit Courbaud, Michael Dietze, Michelle Hersh, Janneke HilleRisLambers et al. (2010) "High‐dimensional coexistence based on individual variation: a synthesis of evidence." Ecological Monographs 80, no. 4 : 569-608. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1541.1

Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux (2023a) "Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure." bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032

Camille Girard‐Tercieux, Isabelle Maréchaux, Adam T. Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Joannès Guillemot et al. (2023b) "Rethinking the nature of intraspecific variability and its consequences on species coexistence." Ecology and Evolution 13, no. 3 : e9860. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9860

Allan Raffard, Frédéric Santoul, Julien Cucherousset, and Simon Blanchet. (2019) "The community and ecosystem consequences of intraspecific diversity: A meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 94, no. 2: 648-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12472