HORTAL Joaquín

- Departament of Biogeography and Global Change, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), Madrid, Spain

- Biodiversity, Biogeography, Biological invasions, Climate change, Coexistence, Community ecology, Experimental ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Theoretical ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 5

Review: 1

Recommendations: 5

Drivers of plant-associated invertebrate community structure in West-European coastal dunes

Combining Joint Species Distribution Models and multivariate techniques allows understanding biogeographical and micro-habitat community responses

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Sergio Chozas, André Mira and 1 anonymous reviewerCommunity structure is determined by the regional species pool – which for simplicity can be assumed to be filtered through dispersal limitations, abiotic conditions, and species coexistence mechanisms (Cornell & Harrison 2014). This filtering involves macroecological constraints, such as energy and space availability, and assembly rules that determine species composition (Diamond 1975; Weiher & Keddy 1995; Guisan & Rahbek 2011; Hortal et al. 2012). But also by a series of processes that determine species distributions across scales, including biogeographical and stochastic processes (e.g., large-scale dispersal and occupancy dynamics within the landscape) and deterministic niche-based responses to abiotic and biotic conditions, which interact across scales (Soberón 2010; Hortal et al. 2010; Brousseau et al. 2018). These processes collectively determine the persistence of species assemblages within communities. It follows that, to understand the processes determining the structure of these communities it is necessary to combine methods analyse the effects of drivers acting on both species distributions and community responses.

Van de Walle et al. (2025) take this integrative approach. The final revised version of their work combines multivariate techniques (in this case a RDA) and Joint SDMs to model the small-scale distribution and structure of the invertebrate communities inhabiting a series of coastal dunes in Southern England, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The paper builds upon well-designed stratified field surveys, which allow them to identify variations at different scales, from geographical to local. These high-quality field data, together with the combination of different modelling techniques, allows them to identify both a clear biogeographical zonation in the structure of these communities, and the existence of a series of neat responses of species to the spatial structure and vigour of the tussocks created by the marram grass fixing the sand dunes. Their models also include the body size, feeding guild and phylogenetic relationships between co-occurring species, although their effects are smaller compared to those of biogeographical differences –which, arguably, are determined by differences in the species pool of each dune system, and species responses to the microhabitat conditions created by the tussocks. They can however identify a trade-off between generalist and specialist species within each community.

Note that here I'm using model in the sense of tools for understanding and explaining complex ecological systems, as advocated by Levins (1966). Which is precisely what Van de Walle et al. (2025) do here. By combining techniques tailored to model species distributions and community-level responses, they (we) gain a much improved understanding of how both species pools and the spatial structure of habitats determine the composition of ecological communities. Importantly, Van de Walle et al. (2025) use this knowledge to obtain key insights about how to manage and restore these endangered habitats, thereby proving the value of this kind of integrative approaches.

References

Brousseau, P.-M., Gravel, D., & Handa, I. T. (2018). On the development of a predictive functional trait approach for studying terrestrial arthropods. Journal of Animal Ecology, 87(5), 1209–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12834

Cornell, H. V., & Harrison, S. P. (2014). What are species pools and when are they important? Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 45(1), 45–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091759

Diamond, J. M. (1975). Assembly of species communities. In M. L. Cody & J. M. Diamond (Eds.), Ecology and Evolution of Communities (pp. 342–444). Harvard University Press.

Guisan, A., & Rahbek, C. (2011). SESAM – a new framework integrating macroecological and species distribution models for predicting spatio-temporal patterns of species assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 38(8), 1433–1444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02550.x

Hortal, J., Roura-Pascual, N., Sanders, N. J., & Rahbek, C. (2010). Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06428.x

Hortal, J., de Marco, P., Santos, A. M. C., & Diniz-Filho, J. A. F. (2012). Integrating biogeographical processes and local community assembly. Journal of Biogeography, 39(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02684.x

Levins, R. (1966). The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421–431.

Soberón, J. (2010). Niche and area of distribution modeling: A population ecology perspective. Ecography, 33(1), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06074.x

van de Walle, R., Dahirel, M., Langeraert, W., Benoit, D., Vantieghem, P., Vandegehuchte, M. L., Massol, F., & Bonte, D. (2025). Drivers of plant-associated invertebrate community structure in West-European coastal dunes. BioRxiv, 2024.06.24.600350, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.24.600350

Weiher, E., & Keddy, P. A. (1995). Assembly rules, null models, and trait dispersion: New questions from old patterns. Oikos, 74(1), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545686

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion

Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environments

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007).

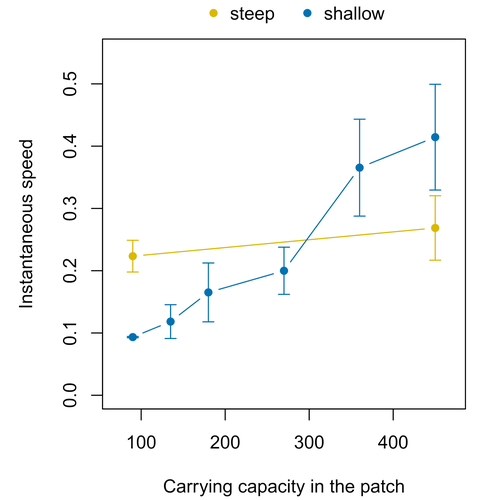

Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients).

Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011).

The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions.

REFERENCES

Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746

Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1

Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431.

Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574

Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255

Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x

Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037

Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x

Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107

Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x

Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit flies

Understanding the interplay between host-specificity, environmental conditions and competition through the sound application of Joint Species Distribution Models

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten DormannUnderstanding why and how species coexist in local communities is one of the central questions in ecology. There is general agreement that species distribution and coexistence are determined by a number of key mechanisms, including the environmental requirements of species, dispersal, evolutionary constraints, resource availability and selection, metapopulation dynamics, and biotic interactions (e.g. Soberón & Nakamura 2009; Colwell & Rangel 2009; Ricklefs 2015). These factors are however intricately intertwined in a scale-structured fashion (Hortal et al. 2010; D’Amen et al. 2017), making it particularly difficult to tease apart the effects of each one of them. This could be addressed by the novel field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling (JSDM; Okasvainen & Abrego 2020), as it allows assessing the effects of several sets of factors and the co-occurrence and/or covariation in abundances of potentially interacting species at the same time (Pollock et al. 2014; Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Dormann et al. 2018). However, the development of JSDM has been hampered by the general lack of good-quality detailed data on species co-occurrences and abundances (see Hortal et al. 2015).

Facon et al. (2021) use a particularly large compilation of field surveys to study the abundance and co-occurrence of Tephritidae fruit flies in c. 400 orchards, gardens and natural areas throughout the island of Réunion. Further, they combine such information with lab data on their host-selection fundamental niche (i.e. in the absence of competitors), codifying traits of female choice and larval performances in 21 host species. They use Poisson Log-Normal models, a type of mixed model that allows one to jointly model the random effects associated with all species, and retrieve the covariations in abundance that are not explained by environmental conditions or differences in sampling effort. Then, they use a series of models to evaluate the effects on these matrices of ecological covariates (date, elevation, habitat, climate and host plant), species interactions (by comparing with a constrained residual variance-covariance matrix) and the species’ host-selection fundamental niches (through separate models for each fly species).

The eight Tephritidae species inhabiting Réunion include both generalists and specialists in Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae with a known history of interspecific competition. Facon et al. (2021) use a comprehensive JSDM approach to assess the effects of different factors separately and altogether. This allows them to identify large effects of plant hosts and the fundamental host-selection niche on species co-occurrence, but also to show that ecological covariates and weak –though not negligible– species interactions are necessary to account for all residual variance in the matrix of joint species abundances per site. Further, they also find evidence that the fitness per host measured in the lab has a strong influence on the abundances in each host plant in the field for specialist species, but not for generalists. Indeed, the stronger effects of competitive exclusion were found in pairs of Cucurbitaceae specialist species. However, these analyses fail to provide solid grounds to assess why generalists are rarely found in Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae. Although they argue that this may be due to Connell’s (1980) ghost of competition past (past competition that led to current niche differentiation), further data on the evolutionary history of these fruit flies is needed to assess this hypothesis.

Finding evidence for the effects of competitive interactions on species’ occurrences and spatial distributions is often difficult, perhaps because these effects occur over longer time scales than the ones usually studied by ecologists (Yackulic 2017). The work by Facon and colleagues shows that weak effects of competition can be detected also at the short ecological timescales that determine coexistence in local communities, under the virtuous combination of good-quality data and sound analytical designs that account for several aspects of species’ niches, their biotopes and their joint population responses. This adds a new dimension to the application of Hutchinson’s (1978) niche framework to understand the spatial dynamics of species and communities (see also Colwell & Rangel 2009), although further advances to incorporate dispersal-driven metacommunity dynamics (see, e.g., Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Leibold et al. 2017) are certainly needed. Nonetheless, this work shows the potential value of in-depth analyses of species coexistence based on combining good-quality field data with well-thought out JSDM applications. If many studies like this are conducted, it is likely that the uprising field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling will improve our understanding of the hierarchical relationships between the different factors affecting species coexistence in ecological communities in the near future.

References

Colwell RK, Rangel TF (2009) Hutchinson’s duality: The once and future niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19651–19658. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901650106

Connell JH (1980) Diversity and the Coevolution of Competitors, or the Ghost of Competition Past. Oikos, 35, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421

D’Amen M, Rahbek C, Zimmermann NE, Guisan A (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222

Dormann CF, Bobrowski M, Dehling DM, Harris DJ, Hartig F, Lischke H, Moretti MD, Pagel J, Pinkert S, Schleuning M, Schmidt SI, Sheppard CS, Steinbauer MJ, Zeuss D, Kraan C (2018) Biotic interactions in species distribution modelling: 10 questions to guide interpretation and avoid false conclusions. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27, 1004–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759

Facon B, Hafsi A, Masselière MC de la, Robin S, Massol F, Dubart M, Chiquet J, Frago E, Chiroleu F, Duyck P-F, Ravigné V (2021) Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of community structure in fruit flies. bioRxiv, 2020.12.07.414326. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326

Hortal J, de Bello F, Diniz-Filho JAF, Lewinsohn TM, Lobo JM, Ladle RJ (2015) Seven Shortfalls that Beset Large-Scale Knowledge of Biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46, 523–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054400

Hortal J, Roura‐Pascual N, Sanders NJ, Rahbek C (2010) Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 33, 51–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06428.x

Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Leibold MA, Chase JM, Ernest SKM (2017) Community assembly and the functioning of ecosystems: how metacommunity processes alter ecosystems attributes. Ecology, 98, 909–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1697

Ovaskainen O, Abrego N (2020) Joint Species Distribution Modelling: With Applications in R. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108591720

Ovaskainen O, Roy DB, Fox R, Anderson BJ (2016) Uncovering hidden spatial structure in species communities with spatially explicit joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12502

Pollock LJ, Tingley R, Morris WK, Golding N, O’Hara RB, Parris KM, Vesk PA, McCarthy MA (2014) Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180

Ricklefs RE (2015) Intrinsic dynamics of the regional community. Ecology Letters, 18, 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12431

Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106

Yackulic CB (2017) Competitive exclusion over broad spatial extents is a slow process: evidence and implications for species distribution modeling. Ecography, 40, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02836

Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation

New light on the baseline importance of temperature for the origin of geographic species richness gradients

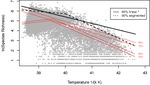

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewersWhether environmental conditions –in particular energy and water availability– are sufficient to account for species richness gradients (e.g. Currie 1991), or the effects of other biotic and historical or regional factors need to be considered as well (e.g. Ricklefs 1987), was the subject of debate during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Francis & Currie 2003; Hawkins et al. 2003, 2006; Currie et al. 2004; Ricklefs 2004). The metabolic theory of ecology (Brown et al. 2004) provided a solid and well-rooted theoretical support for the preponderance of energy as the main driver for richness variations. As any good piece of theory, it provided testable predictions about the sign and shape (i.e. slope) of the relationship between temperature –a key aspect of ambient energy– and species richness. However, these predictions were not supported by empirical evaluations (e.g. Kreft & Jetz 2007; Algar et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 2007a), as the effects of a myriad of other environmental gradients, regional factors and evolutionary processes result in a wide variety of richness–temperature responses across different groups and regions (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Hortal et al. 2008). So, in a textbook example of how good theoretical work helps advancing science even if proves to be (partially) wrong, the evaluation of this aspect of the metabolic theory of ecology led to current understanding that, while species richness does respond to current climatic conditions, many other ecological, evolutionary and historical factors do modify such response across scales (see, e.g., Ricklefs 2008; Hawkins 2008; D’Amen et al. 2017). And the kinetic model linking mean annual temperature and species richness (Allen et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2004) was put aside as being, perhaps, another piece of the puzzle of the origin of current diversity gradients.

Segovia (2021) puts together an elegant way of reinvigorating this part of the metabolic theory of ecology. He uses quantile regressions to model just the upper parts of the relationship between species richness and mean annual temperature, rather than modelling its central tendency through the classical linear regression family of methods –as was done in the past. This assumes that the baseline effect of ambient energy does produce the negative linear relationship between richness and temperature predicted by the kinetic model (Allen et al. 2002), but also that this effect only poses an upper limit for species richness, and the effects of other factors may result in lower levels of species co-occurrence, thus producing a triangular rather than linear relationship. The results of Segovia’s simple and elegant analytical design show unequivocally that the predictions of the kinetic model become progressively more explanatory towards the upper quartiles of the relationship between species richness and temperature along over 10,000 tree local inventories throughout the Americas, reaching over 70% of explanatory power for the upper 5% of the relationship (i.e. the 95% quantile). This confirms to a large extent his reformulation of the predictions of the kinetic model.

Further, the neat study from Segovia (2021) also provides evidence confirming that the well-known spatial non-stationarity in the richness–temperature relationship (see Cassemiro et al. 2007) also applies to its upper-bound segment. Both the explanatory power and the slope of the relationship in the 95% upper quantile vary widely between biomes, reaching values similar to the predictions of the kinetic model only in cold temperate environments –precisely where temperature becomes more important than water availability as a constrain to plant life (O’Brien 1998; Hawkins et al. 2003). Part of these variations are indeed related with changes in water deficit and number of frost days along the XXth Century, as shown by the residuals of this paper (Segovia 2021) and a more detailed separate study (Segovia et al. 2020). This pinpoints the importance of the relative balance between water and energy as two of the main climatic factors constraining species diversity gradients, confirming the value of hypotheses that date back to Humboldt’s work (see Hawkins 2001, 2008). There is however a significant amount of unexplained variation in Segovia’s analyses, in particular in the progressive departure of the predictions of the kinetic model as we move towards the tropics, or downwards along the lower quantiles of the richness–temperature relationship. This calls for a deeper exploration of the factors that modify the baseline relationship between richness and energy, opening a new avenue for the macroecological investigation of how different forces and processes shape up geographical diversity gradients beyond the mere energetic constrains imposed by the basal limitations of multicellular life on Earth.

References

Algar, A.C., Kerr, J.T. and Currie, D.J. (2007) A test of Metabolic Theory as the mechanism underlying broad-scale species-richness gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 170-178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00275.x

Allen, A.P., Brown, J.H. and Gillooly, J.F. (2002) Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science, 297, 1545-1548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072380

Brown, J.H., Gillooly, J.F., Allen, A.P., Savage, V.M. and West, G.B. (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology, 85, 1771-1789. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-9000

Cassemiro, F.A.d.S., Barreto, B.d.S., Rangel, T.F.L.V.B. and Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. (2007) Non-stationarity, diversity gradients and the metabolic theory of ecology. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 820-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00332.x

Currie, D.J. (1991) Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist, 137, 27-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/285144

Currie, D.J., Mittelbach, G.G., Cornell, H.V., Field, R., Guegan, J.-F., Hawkins, B.A., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2004) Predictions and tests of climate-based hypotheses of broad-scale variation in taxonomic richness. Ecology Letters, 7, 1121-1134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00671.x

D'Amen, M., Rahbek, C., Zimmermann, N.E. and Guisan, A. (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222

Francis, A.P. and Currie, D.J. (2003) A globally consistent richness-climate relationship for Angiosperms. American Naturalist, 161, 523-536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/368223

Hawkins, B.A. (2001) Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8

Hawkins, B.A. (2008) Recent progress toward understanding the global diversity gradient. IBS Newsletter, 6.1, 5-8. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr2k1dd

Hawkins, B.A., Field, R., Cornell, H.V., Currie, D.J., Guégan, J.-F., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Mittelbach, G.G., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E., Porter, E.E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2003) Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology, 84, 3105-3117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8006

Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Jaramillo, C.A. and Soeller, S.A. (2006) Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 770-780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01452.x

Hawkins, B.A., Albuquerque, F.S., Araújo, M.B., Beck, J., Bini, L.M., Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J., Castro Parga, I., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Ferrer-Castán, D., Field, R., Gómez, J.F., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Kitching, I.J., León-Cortés, J.L., et al. (2007a) A global evaluation of metabolic theory as an explanation for terrestrial species richness gradients. Ecology, 88, 1877-1888. doi:10.1890/06-1444.1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1444.1

Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Bini, L.M., Araújo, M.B., Field, R., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Rahbek, C., Rodríguez, M.Á. and Sanders, N.J. (2007b) Metabolic theory and diversity gradients: Where do we go from here? Ecology, 88, 1898–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-2141.1

Hortal, J., Rodríguez, J., Nieto-Díaz, M. and Lobo, J.M. (2008) Regional and environmental effects on the species richness of mammal assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 35, 1202–1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01850.x

Kreft, H. and Jetz, W. (2007) Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104, 5925-5930. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608361104

O'Brien, E. (1998) Water-energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 379-398. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x

Ricklefs, R.E. (1987) Community diversity: Relative roles of local and regional processes. Science, 235, 167-171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4785.167

Ricklefs, R.E. (2004) A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 7, 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00554.x

Ricklefs, R.E. (2008) Disintegration of the ecological community. American Naturalist, 172, 741-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/593002

Segovia, R.A. (2021) Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation. bioRxiv, 836338, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/836338

Segovia, R.A., Pennington, R.T., Baker, T.R., Coelho de Souza, F., Neves, D.M., Davis, C.C., Armesto, J.J., Olivera-Filho, A.T. and Dexter, K.G. (2020) Freezing and water availability structure the evolutionary diversity of trees across the Americas. Science Advances, 6, eaaz5373. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5373

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands

A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamics

Recommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter ConveyPolar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). Bazzichetto et al. (2020) use data from a detailed inventory, SDMs and trait data altogether to assess the drivers of invasion success of six alien plants on Possession Island, in the remote sub-Antarctic archipelago of Crozet. SDMs have inherent limitations to describe different aspects of species distributions, including the fundamental niche and, with it, the areas that could host viable populations (Hortal et al. 2012). Therefore, their utility to predict future biological invasions is limited (Jiménez-Valverde et al. 2011). However, they can be powerful tools to describe species range dynamics if they are thoughtfully used by adopting conscious decisions about the techniques and data used, and interpreting carefully the actual implications of their results. This is what Bazzichetto et al. (2020) do, using General Linear Models (GLM) –a technique well rooted in the original niche-based SDM theory (e.g. Austin 1990)– that can provide a meaningful description of the realized niche within the limits of an adequately sampled region. Further, as alien species share and are similarly affected by several steps of the invasion process (Richardson et al. 2000), these authors model the realized distribution of the six species altogether. This can be done through the recently developed joint-SDM, a group of techniques where the co-occurrence of the modelled species is explicitly taken into account during modelling (e.g. Pollock et al. 2014). Here, the addition of species traits has been identified as a key step to understand the associations of species in space (see Dormann et al. 2018). Bazzichetto et al. (2020) combine their GLM-based SDM for each species with a so-called multi-SDM approach, where they assess together the consistency in the interactions between both species and topographically-driven climate variations, and several plant traits and two key anthropic factors –accessibility from human settlements and distance to hiking paths. This work is a good example on how a theoretically meaningful SDM approach can provide useful –though perhaps not deep– insights on biological invasions for remote landscapes threatened by biotic homogenization. By combining climate and topographic variables as proxies for the spatial variations in the abiotic conditions regulating plant growth, measures of accessibility, and traits of the plant invaders, Bazzichetto et al. (2020) are able to identify the different effects that the interactions between the potential intensity of propagule dissemination by humans, and the ecological characteristics of the invaders themselves, may have on their invasion success. The innovation of modelling together species responses is important because it allows dissecting the spatial dynamics of spread of the invaders, which indeed vary according to a handful of their traits. For example, their results show that no all old residents have profited from the larger time of residence in the island, as Poa pratensis is seemingly as dependent of a higher intensity of human activity as the newcomer invaders in general are. According to Bazzichetto et al. trait-based analyses, these differences are apparently related with plant height, as smaller plants disperse more easily. Further, being perennial also provides an advantage for the persistence in areas with less human influence. This puts name, shame and fame to the known influence of plant life history on their dispersal success (Beckman et al. 2018), at least for the particular case of plant invasions in Possession Island. Of course this approach has limitations, as data on the texture, chemistry and temperature of the soil are not available, and thus were not considered in the analyses. These factors may be critical for both establishment and persistence of small plants in the harsh Antarctic environments, as Bazzichetto et al. (2020) recognize. But all in all, their results provide key insights on which traits may confer alien plants with a higher likelihood of becoming successful invaders in the fragile Antarctic and sub-Antarctic ecosystems. This opens a way for rapid assessments of invasibility, which will help identifying which species in the process of naturalizing may require active contention measures to prevent them from becoming ecological game changers and cause disastrous cascade effects that shift the dynamics of native ecosystems. **References** Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: [https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043](https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043) Bazzichetto, M., Massol, F., Carboni, M., Lenoir, J., Lembrechts, J. J. and Joly, R. (2020) Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands. bioRxiv, 2020.07.19.210880, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880](https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880) Beckman, N. G., Bullock, J. M., and Salguero-Gómez, R. (2018). High dispersal ability is related to fast life-history strategies. Journal of Ecology, 106(4), 1349-1362. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12989](https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12989) Croll, D. A., Maron, J. L., Estes, J. A., Danner, E. M., and Byrd, G. V. (2005). Introduced predators transform subarctic islands from grassland to tundra. Science, 307(5717), 1959-1961. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1108485](https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1108485) Dormann, C. F., Bobrowski, M., Dehling, D. M., Harris, D. J., Hartig, F., Lischke, H., Moretti, M. D., Pagel, J., Pinkert, S., Schleuning, M., Schmidt, S. I., Sheppard, C. S., Steinbauer, M. J., Zeuss, D., and Kraan, C. (2018). Biotic interactions in species distribution modelling: 10 questions to guide interpretation and avoid false conclusions. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27(9), 1004-1016. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759](https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759) Jiménez-Valverde, A., Peterson, A., Soberón, J., Overton, J., Aragón, P., and Lobo, J. (2011). Use of niche models in invasive species risk assessments. Biological Invasions, 13(12), 2785-2797. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9963-4](https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9963-4) Hortal, J., Lobo, J. M., and Jiménez-Valverde, A. (2012). Basic questions in biogeography and the (lack of) simplicity of species distributions: Putting species distribution models in the right place. Natureza & Conservação – Brazilian Journal of Nature Conservation, 10(2), 108-118. doi: [https://doi.org/10.4322/natcon.2012.029](https://doi.org/10.4322/natcon.2012.029) Hughes, K. A., Pertierra, L. R., Molina-Montenegro, M. A., and Convey, P. (2015). Biological invasions in terrestrial Antarctica: what is the current status and can we respond? Biodiversity and Conservation, 24(5), 1031-1055. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-0896-6](https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-0896-6) Pertierra, L. R., Baker, M., Howard, C., Vega, G. C., Olalla-Tarraga, M. A., and Scott, J. (2016). Assessing the invasive risk of two non-native Agrostis species on sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island. Polar Biology, 39(12), 2361-2371. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-016-1912-3](https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-016-1912-3) Pollock, L. J., Tingley, R., Morris, W. K., Golding, N., O'Hara, R. B., Parris, K. M., Vesk, P. A., and McCarthy, M. A. (2014). Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5(5), 397-406. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180](https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180) Richardson, D. M., Pyšek, P., Rejmánek, M., Barbour, M. G., Panetta, F. D., and West, C. J. (2000). Naturalization and invasion of alien plants: concepts and definitions. Diversity and Distributions, 6(2), 93-107. doi: [https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-4642.2000.00083.x](https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-4642.2000.00083.x)

Review: 1

Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community composition

On the importance of temporal meta-community dynamics for our understanding of assembly processes

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Joaquín Hortal and 2 anonymous reviewersThe processes that trigger community assembly are still in the centre of ecological interest. While prior work mostly focused on spatial patterns of co-occurrence within a meta-community framework [reviewed in 1, 2] recent studies also include temporal patterns of community composition [e.g. 3, 4, 5, 6]. In this preprint [7], Franck Jabot and co-workers extend they prior approaches to quasi neutral community assembly [8, 9, 10] and develop an analytical framework of spatial and temporal diversity turnover. A simple and heuristic path model for beta diversity and an extended ecological drift model serve as starting points. The model can be seen as a counterpart to Ulrich et al. [5]. These authors implemented competitive hierarchies into their neutral meta-community model while the present paper focuses on environmental filtering. Most important, the model and parameterization of four empirical data sets on aquatic plant and animal meta-communities used by Jabot et al. returned a consistent high influence of environmental stochasticity on species turnover. Of course, this major result does not come to a surprise. As typical for this kind of models it depends also to a good deal on the initial model settings. It nevertheless makes a strong conceptual point for the importance of environmental variability over dispersal and richness effects. One interesting side effect regards the impact of richness differences (ΔS). Jabot et al. interpret this as a ‘nuisance variable’ as they do not have a stringent explanation. Of course, it might be a pure statistical bias introduced by the Soerensen metric of turnover that is normalized by richness. However, I suspect that there is more behind the ΔS effect. Richness differences are generally associated with respective differences in total abundances and introduce source – sink dynamics that inevitably shape subsequent colonization – extinction processes. It would be interesting to see whether ΔS alone is able to trigger observed patterns of community assembly and community composition. Such an analysis would require partitioning of species turnover into richness and nestedness effects [11]. I encourage Jabot et al. to undertake such an effort.

The present paper is also another call to include temporal population variability into metapopulation models for a better understanding of the dynamics and triggering of community assembly. In a next step, competitive interactions should be included into the model to infer the relative importance of both factors.

References

[1] Götzenberger, L. et al. (2012). Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological reviews, 87(1), 111-127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00187.x

[2] Ulrich, W., & Gotelli, N. J. (2013). Pattern detection in null model analysis. Oikos, 122(1), 2-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20325.x

[3] Grilli, J., Barabás, G., Michalska-Smith, M. J., & Allesina, S. (2017). Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature, 548(7666), 210. doi: 10.1038/nature23273

[4] Nuvoloni, F. M., Feres, R. J. F., & Gilbert, B. (2016). Species turnover through time: colonization and extinction dynamics across metacommunities. The American Naturalist, 187(6), 786-796. doi: 10.1086/686150

[5] Ulrich, W., Jabot, F., & Gotelli, N. J. (2017). Competitive interactions change the pattern of species co‐occurrences under neutral dispersal. Oikos, 126(1), 91-100. doi: 10.1111/oik.03392

[6] Dobramysl, U., Mobilia, M., Pleimling, M., & Täuber, U. C. (2018). Stochastic population dynamics in spatially extended predator–prey systems. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 51(6), 063001. doi: 10.1088/1751-8121/aa95c7

[7] Jabot, F., Laroche, F., Massol, F., Arthaud, F., Crabot, J., Dubart, M., Blanchet, S., Munoz, F., David, P., and Datry, T. (2019). Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community composition. bioRxiv, 480335, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/480335

[8] Jabot, F., & Chave, J. (2011). Analyzing tropical forest tree species abundance distributions using a nonneutral model and through approximate Bayesian inference. The American Naturalist, 178(2), E37-E47. doi: 10.1086/660829

[9] Jabot, F., & Lohier, T. (2016). Non‐random correlation of species dynamics in tropical tree communities. Oikos, 125(12), 1733-1742. doi: 10.1111/oik.03103

[10] Datry, T., Bonada, N., & Heino, J. (2016). Towards understanding the organisation of metacommunities in highly dynamic ecological systems. Oikos, 125(2), 149-159. doi: 10.1111/oik.02922

[11] Baselga, A. (2010). Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Global ecology and biogeography, 19(1), 134-143. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00490.x