ULRICH Werner

- Department of Ecology and Biogeography, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, Poland

- Biodiversity, Biogeography, Community ecology, Ecological successions, Macroecology, Meta-analyses, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 5

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 5

Scales of marine endemism in oceanic islands and the Provincial-Island endemism

Provincial-island endemism adds to our understanding of the geographical distribution of species

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Paulo Borges and 1 anonymous reviewerMany ecological, evolutionary, biogeographic studies on animals and plants have focused on endemism (e.g. (Crisp et al., 2001; Kier et al., 2009; Matthews et al., 2024, 2022; Qian et al., 2024). Ecological hotspots were first defined on endemic species (Myers et al., 2000). Nevertheless, despite the fact that the concept of endemism is crucial in biogeography and also in palaeontology there is still no stringent definition of endemism and very different concepts of endemism are used. It is another example of a concept that tries to define the undefinable (Darwin, 1859). ‘Definitions’ are either based on geographic and genetic isolation (Myers et al., 2000; Qian et al., 2024) or founded in geometric approaches that define restricted range sizes (Kinzig and Harte, 2000). Often, an ad hoc concept is used to cover taxon specificity and the habitats studied.

Pinheiro et al. (2025) focus on species restricted to oceanic islands and rightly remark that these work as cradles for species origination and also as museums that contribute to lineages persistence. However, they also notice that in the case of islands any definition of endemism from species occurring only on single islands would be too narrow. Rather, endemism shows a spatial scaling with an increasing number of species occurring of multiple islands. In this respect they introduce the concept of provincial-island endemism and study the importance of single and multiple-island endemic species to island biodiversity

Pinheiro et al. (2025) use data from 7,289 fish species associated with reef environments of 87 oceanic islands and 189 coastal reefs around the world. A strong negative correlation appeared between the number of endemic species and the number of islands they occur. This relationship directly translates into our assessment of whether an archipelago is rich or poor in endemics. Pinheiro et al. (2025) explicitly demonstrate this with the examples of the Hawaiian Islands and Rapa Nui. They conclude that biogeographers need to clarify whether they deal with single-island or multiple island endemics. We can adapt this distinction to terrestrial and freshwater habitats and differentiate between single and multiple restricted areas and water bodies, for instance rivers, lakes, alpine valleys, mountains, or deserts.

Of course, the idea that endemism patterns are scale dependent is not new. Daru et al. (2020), Graham et al. (2018), or Keil et al. (2015) already noticed the importance of spatial scale and Townsend Peterson and Watson (1998) introduced the partly equivalent concepts of weighted spatial and phylogenetic endemism that also contain the scaling component. Pinheiro et al. (2025) add to this by providing a sound analysis of the strength of the scaling component. They argue that fish endangerment categories and fishery limits might change when considering multiple island endemics.

References

Crisp, M.D., Laffan, S., Linder, H.P., Monro, A., 2001. Endemism in the Australian flora. J. Biogeogr. 28, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00524.x

Daru, B.H., Farooq, H., Antonelli, A., Faurby, S., 2020. Endemism patterns are scale dependent. Nat. Commun. 11, 2115. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15921-6

Darwin, C., 1859. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. John Murray, London.

Graham, C.H., Storch, D., Machac, A., 2018. Phylogenetic scale in ecology and evolution. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12686

Keil, P., Storch, D., Jetz, W., 2015. On the decline of biodiversity due to area loss. Nat. Commun. 6, 8837. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9837

Kier, G., Kreft, H., Lee, T.M., Jetz, W., Ibisch, P.L., Nowicki, C., Mutke, J., Barthlott, W., 2009. A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 9322–9327. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810306106

Kinzig, A.P., Harte, J., 2000. Implications of Endemics–Area Relationships for Estimates of Species Extinctions. Ecology 81, 3305–3311. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[3305:IOEARF]2.0.CO;2

Matthews, T.J., Triantis, K.A., Wayman, J.P., Martin, T.E., Hume, J.P., Cardoso, P., Faurby, S., Mendenhall, C.D., Dufour, P., Rigal, F., Cooke, R., Whittaker, R.J., Pigot, A.L., Thébaud, C., Jørgensen, M.W., Benavides, E., Soares, F.C., Ulrich, W., Kubota, Y., Sadler, J.P., Tobias, J.A., Sayol, F., 2024. The global loss of avian functional and phylogenetic diversity from anthropogenic extinctions. Science 386, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk7898

Matthews, T.J., Wayman, J.P., Cardoso, P., Sayol, F., Hume, J.P., Ulrich, W., Tobias, J.A., Soares, F.C., Thébaud, C., Martin, T.E., Triantis, K.A., 2022. Threatened and extinct island endemic birds of the world: Distribution, threats and functional diversity. J. Biogeogr. 49, 1920–1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14474

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R.A., Mittermeier, C.G., da Fonseca, G.A.B., Kent, J., 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501

Pinheiro, H.T., Rocha, L.A., Quimbayo, J.P 2025. Scales of marine endemism in oceanic islands and the Provincial-Island endemism. bioRxiv, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.12.603346

Qian, H., Mishler, B.D., Zhang, J., Qian, S., 2024. Global patterns and ecological drivers of taxonomic and phylogenetic endemism in angiosperm genera. Plant Divers. 46, 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2023.11.004

Townsend Peterson, A., Watson, D.M., 1998. Problems with areal definitions of endemism: the effects of spatial scaling. Divers. Distrib. 4, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-4642.1998.00021.x

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct

Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?

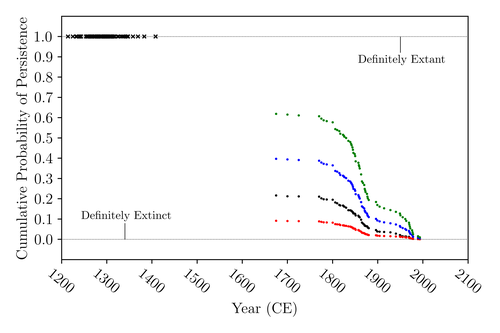

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard HoldawayAncient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century?

The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable.

The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450.

References

Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261

Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities

How does spatial heterogeneity affect stability of trophic metacommunities?

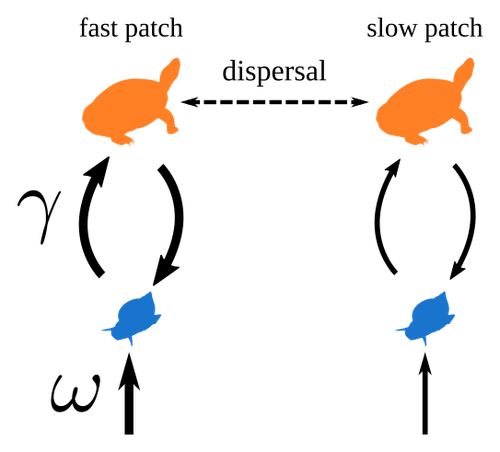

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko, Ludek Berec and Diogo ProveteThe temporal or spatial variability in species population sizes and interaction strength of animal and plant communities has a strong impact on aggregate community properties (for instance biomass), community composition, and species richness (Kokkoris et al. 2002). Early work on spatial and temporal variability strongly indicated that asynchronous population and environmental fluctuations tend to stabilise community structures and diversity (e.g. Holt 1984, Tilman and Pacala 1993, McCann et al. 1998, Amarasekare and Nisbet 2001). Similarly, trophic networks might be stabilised by spatial heterogeneity (Hastings 1977) and an asymmetry of energy flows along food chains (Rooney et al. 2006). The interplay between temporal, spatial, and trophic heterogeneity within the meta-community concept has got much less interest. In the recent preprint in PCI Ecology, Quévreux et al. (2023) report that Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. These authors rightly notice that the interplay between trophic and spatial heterogeneity might induce contrasting effects depending on the internal dynamics of the system. Their contribution builds on prior work (Quévreux et al. 2021a, b) on perturbed trophic cascades.

I found this paper particularly interesting because it is in the, now century-old, tradition to show that ecological things are not so easy. Since the 1930th, when Nicholson and Baily and others demonstrated that simple deterministic population models might generate stability and (pseudo-)chaos ecologists have realised that systems triggered by two or more independent processes might be intrinsically unpredictable and generate different outputs depending on the initial parameter settings. This resembles the three-body problem in physics. The present contribution of Quévreux et al. (2023) extends this knowledge to an example of a spatially explicit trophic model. Their main take-home message is that asymmetric energy flows in predator–prey relationships might have contrasting effects on the stability of metacommunities receiving localised perturbations. Stability is context dependent.

Of course, the work is merely a theoretical exercise using a simplistic trophic model. It demands verification with field data. Nevertheless, we might expect even stronger unpredictability in more realistic multitrophic situations. Therefore, it should be seen as a proof of concept. Remember that increasing trophic connectance tends to destabilise food webs (May 1972). In this respect, I found the final outlook to bioconservation ambitious but substantiated. Biodiversity management needs a holistic approach focusing on all aspects of ecological functioning. I would add the need to see stability and biodiversity within an evolutionary perspective.

References

Amarasekare P, Nisbet RM (2001) Spatial Heterogeneity, Source‐Sink Dynamics, and the Local Coexistence of Competing Species. The American Naturalist, 158, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1086/323586

Hastings A (1977) Spatial heterogeneity and the stability of predator-prey systems. Theoretical Population Biology, 12, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(77)90034-X

Holt RD (1984) Spatial Heterogeneity, Indirect Interactions, and the Coexistence of Prey Species. The American Naturalist, 124, 377–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/284280

Kokkoris GD, Jansen VAA, Loreau M, Troumbis AY (2002) Variability in interaction strength and implications for biodiversity. Journal of Animal Ecology, 71, 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00604.x

May RM (1972) Will a Large Complex System be Stable? Nature, 238, 413–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/238413a0

McCann K, Hastings A, Huxel GR (1998) Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature, 395, 794–798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427

Quévreux P, Barbier M, Loreau M (2021) Synchrony and Perturbation Transmission in Trophic Metacommunities. The American Naturalist, 197, E188–E203. https://doi.org/10.1086/714131

Quévreux P, Pigeault R, Loreau M (2021) Predator avoidance and foraging for food shape synchrony and response to perturbations in trophic metacommunities. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 528, 110836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110836

Quévreux P, Haegeman B, Loreau M (2023) Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. hal-03829838, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.science/hal-03829838

Rooney N, McCann K, Gellner G, Moore JC (2006) Structural asymmetry and the stability of diverse food webs. Nature, 442, 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04887

Tilman D, Pacala S (1993) The maintenance of species richness in plant communities. In: Ricklefs, R.E., Schluter, D. (eds) Species Diversity in Ecological Communities: Historical and Geographical Perspectives. University of Chicago Press, pp. 13–25.

Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes

Complex but positive diversity - ecosystem functioning relationships in Riparian tropical forests

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMany ecological drivers can impact ecosystem functionality and multifunctionality, with the latter describing the joint impact of different functions on ecosystem performance and services. It is now generally accepted that taxonomically richer ecosystems are better able to sustain high aggregate functionality measures, like energy transfer, productivity or carbon storage (Buzhdygan 2020, Naeem et al. 2009), and different ecosystem services (Marselle et al. 2021) than those that are less rich. Antonini et al. (2022) analysed an impressive dataset on animal and plant richness of tropical riparian forests and abundances, together with data on key soil parameters. Their work highlights the importance of biodiversity on functioning, while accounting for a manifold of potentially covarying drivers. Although the key result might not come as a surprise, it is a useful contribution to the diversity - ecosystem functioning topic, because it is underpinned with data from tropical habitats. To date, most analyses have focused on temperate habitats, using data often obtained from controlled experiments.

The paper also highlights that diversity–functioning relationships are complicated. Drivers of functionality vary from site to site and each measure of functioning, including parameters as demonstrated here, can be influenced by very different sets of predictors, often associated with taxonomic and trait diversity. Single correlative comparisons of certain aspects of diversity and functionality might therefore return very different results. Antonini et al. (2022) show that, in general, using 22 predictors of functional diversity, varying predictor subsets were positively associated with soil functioning. Correlational analyses alone cannot resolve the question of causal link. Future studies should therefore focus on inferring precise mechanisms behind the observed relationships, and the environmental constraints on predictor subset composition and strength.

References

Antonini Y, Beirão MV, Costa FV, Azevedo CS, Wojakowski MM, Kozovits AR, Pires MRS, Sousa HC de, Messias MCTB, Fujaco MA, Leite MGP, Vidigal JP, Monteiro GF, Dirzo R (2022) Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2021.09.08.459375, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375

Buzhdygan OY, Meyer ST, Weisser WW, Eisenhauer N, Ebeling A, Borrett SR, Buchmann N, Cortois R, De Deyn GB, de Kroon H, Gleixner G, Hertzog LR, Hines J, Lange M, Mommer L, Ravenek J, Scherber C, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Scheu S, Schmid B, Steinauer K, Strecker T, Tietjen B, Vogel A, Weigelt A, Petermann JS (2020) Biodiversity increases multitrophic energy use efficiency, flow and storage in grasslands. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1123-8

Marselle MR, Hartig T, Cox DTC, de Bell S, Knapp S, Lindley S, Triguero-Mas M, Böhning-Gaese K, Braubach M, Cook PA, de Vries S, Heintz-Buschart A, Hofmann M, Irvine KN, Kabisch N, Kolek F, Kraemer R, Markevych I, Martens D, Müller R, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Potts JM, Stadler J, Walton S, Warber SL, Bonn A (2021) Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International, 150, 106420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106420

Naeem S, Bunker DE, Hector A, Loreau M, Perrings C (Eds.) (2009) Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning, and Human Wellbeing: An Ecological and Economic Perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199547951.001.0001

Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community composition

On the importance of temporal meta-community dynamics for our understanding of assembly processes

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Joaquín Hortal and 2 anonymous reviewersThe processes that trigger community assembly are still in the centre of ecological interest. While prior work mostly focused on spatial patterns of co-occurrence within a meta-community framework [reviewed in 1, 2] recent studies also include temporal patterns of community composition [e.g. 3, 4, 5, 6]. In this preprint [7], Franck Jabot and co-workers extend they prior approaches to quasi neutral community assembly [8, 9, 10] and develop an analytical framework of spatial and temporal diversity turnover. A simple and heuristic path model for beta diversity and an extended ecological drift model serve as starting points. The model can be seen as a counterpart to Ulrich et al. [5]. These authors implemented competitive hierarchies into their neutral meta-community model while the present paper focuses on environmental filtering. Most important, the model and parameterization of four empirical data sets on aquatic plant and animal meta-communities used by Jabot et al. returned a consistent high influence of environmental stochasticity on species turnover. Of course, this major result does not come to a surprise. As typical for this kind of models it depends also to a good deal on the initial model settings. It nevertheless makes a strong conceptual point for the importance of environmental variability over dispersal and richness effects. One interesting side effect regards the impact of richness differences (ΔS). Jabot et al. interpret this as a ‘nuisance variable’ as they do not have a stringent explanation. Of course, it might be a pure statistical bias introduced by the Soerensen metric of turnover that is normalized by richness. However, I suspect that there is more behind the ΔS effect. Richness differences are generally associated with respective differences in total abundances and introduce source – sink dynamics that inevitably shape subsequent colonization – extinction processes. It would be interesting to see whether ΔS alone is able to trigger observed patterns of community assembly and community composition. Such an analysis would require partitioning of species turnover into richness and nestedness effects [11]. I encourage Jabot et al. to undertake such an effort.

The present paper is also another call to include temporal population variability into metapopulation models for a better understanding of the dynamics and triggering of community assembly. In a next step, competitive interactions should be included into the model to infer the relative importance of both factors.

References

[1] Götzenberger, L. et al. (2012). Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological reviews, 87(1), 111-127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00187.x

[2] Ulrich, W., & Gotelli, N. J. (2013). Pattern detection in null model analysis. Oikos, 122(1), 2-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20325.x

[3] Grilli, J., Barabás, G., Michalska-Smith, M. J., & Allesina, S. (2017). Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature, 548(7666), 210. doi: 10.1038/nature23273

[4] Nuvoloni, F. M., Feres, R. J. F., & Gilbert, B. (2016). Species turnover through time: colonization and extinction dynamics across metacommunities. The American Naturalist, 187(6), 786-796. doi: 10.1086/686150

[5] Ulrich, W., Jabot, F., & Gotelli, N. J. (2017). Competitive interactions change the pattern of species co‐occurrences under neutral dispersal. Oikos, 126(1), 91-100. doi: 10.1111/oik.03392

[6] Dobramysl, U., Mobilia, M., Pleimling, M., & Täuber, U. C. (2018). Stochastic population dynamics in spatially extended predator–prey systems. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 51(6), 063001. doi: 10.1088/1751-8121/aa95c7

[7] Jabot, F., Laroche, F., Massol, F., Arthaud, F., Crabot, J., Dubart, M., Blanchet, S., Munoz, F., David, P., and Datry, T. (2019). Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community composition. bioRxiv, 480335, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/480335

[8] Jabot, F., & Chave, J. (2011). Analyzing tropical forest tree species abundance distributions using a nonneutral model and through approximate Bayesian inference. The American Naturalist, 178(2), E37-E47. doi: 10.1086/660829

[9] Jabot, F., & Lohier, T. (2016). Non‐random correlation of species dynamics in tropical tree communities. Oikos, 125(12), 1733-1742. doi: 10.1111/oik.03103

[10] Datry, T., Bonada, N., & Heino, J. (2016). Towards understanding the organisation of metacommunities in highly dynamic ecological systems. Oikos, 125(2), 149-159. doi: 10.1111/oik.02922

[11] Baselga, A. (2010). Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Global ecology and biogeography, 19(1), 134-143. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00490.x