ALONSO David

- Computational and Theoretical Ecology, Spanish National Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), Blanes, Spain

- Agroecology, Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Demography, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Ecological successions, Food webs, Foraging, Host-parasite interactions, Macroecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology

- recommender

Recommendations: 3

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 3

Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns

The impact of process at different scales on diversity and ecosystem functioning: a huge challenge

Recommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewerScale is a big topic in ecology [1]. Environmental variation happens at particular scales. The typical scale at which organisms disperse is species-specific, but, as a first approximation, an ensemble of similar species, for instance, trees, could be considered to share a typical dispersal scale. Finally, characteristic spatial scales of species interactions are, in general, different from the typical scales of dispersal and environmental variation. Therefore, conceptually, we can distinguish these three characteristic spatial scales associated with three different processes: species selection for a given environment (E), dispersal (D), and species interactions (I), respectively.

From the famous species-area relation to the spatial distribution of biomass and species richness, the different macro-ecological patterns we usually study emerge from an interplay between dispersal and local interactions in a physical environment that constrains species establishment and persistence in every location. To make things even more complicated, local environments are often modified by the species that thrive in them, which establishes feedback loops. It is usually assumed that local interactions are short-range in comparison with species dispersal, and dispersal scales are typically smaller than the scales at which the environment varies (I < D < E, see [2]), but this should not always be the case.

The authors of this paper [2] relax this typical assumption and develop a theoretical framework to study how diversity and ecosystem functioning are affected by different relations between the typical scales governing interactions, dispersal, and environmental variation. This is a huge challenge. First, diversity and ecosystem functioning across space and time have been empirically characterized through a wide variety of macro-ecological patterns. Second, accommodating local interactions, dispersal and environmental variation and species environmental preferences to model spatiotemporal dynamics of full ecological communities can be done also in a lot of different ways. One can ask if the particular approach suggested by the authors is the best choice in the sense of producing robust results, this is, results that would be predicted by alternative modeling approaches and mathematical analyses [3]. The recommendation here is to read through and judge by yourself.

The main unusual assumption underlying the model suggested by the authors is non-local species interactions. They introduce interaction kernels to weigh the strength of the ecological interaction with distance, which gives rise to a system of coupled integro-differential equations. This kernel is the key component that allows for control and varies the scale of ecological interactions. Although this is not new in ecology [4], and certainly has a long tradition in physics ---think about the electric or the gravity field, this approach has been widely overlooked in the development of the set of theoretical frameworks we have been using over and over again in community ecology, such as the Lotka-Volterra equations or, more recently, the metacommunity concept [5].

In Physics, classic fields have been revised to account for the fact that information cannot travel faster than light. In an analogous way, a focal individual cannot feel the presence of distant neighbors instantaneously. Therefore, non-local interactions do not exist in ecological communities. As the authors of this paper point out, they emerge in an effective way as a result of non-random movements, for instance, when individuals go regularly back and forth between environments (see [6], for an application to infectious diseases), or even migrate between regions. And, on top of this type of movement, species also tend to disperse and colonize close (or far) environments. Individual mobility and dispersal are then two types of movements, characterized by different spatial-temporal scales in general. Species dispersal, on the one hand, and individual directed movements underlying species interactions, on the other, are themselves diverse across species, but it is clear that they exist and belong to two distinct categories.

In spite of the long and rich exchange between the authors' team and the reviewers, it was not finally clear (at least, to me and to one of the reviewers) whether the model for the spatio-temporal dynamics of the ecological community (see Eq (1) in [2]) is only presented as a coupled system of integro-differential equations on a continuous landscape for pedagogical reasons, but then modeled on a discrete regular grid for computational convenience. In the latter case, the system represents a regular network of local communities, becomes a system of coupled ODEs, and can be numerically integrated through the use of standard algorithms. By contrast, in the former case, the system is meant to truly represent a community that develops on continuous time and space, as in reaction-diffusion systems. In that case, one should keep in mind that numerical instabilities can arise as an artifact when integrating both local and non-local spatio-temporal systems. Spatial patterns could be then transient or simply result from these instabilities. Therefore, when analyzing spatiotemporal integro-differential equations, special attention should be paid to the use of the right numerical algorithms. The authors share all their code at https://zenodo.org/record/5543191, and all this can be checked out. In any case, the whole discussion between the authors and the reviewers has inherent value in itself, because it touches on several limitations and/or strengths of the author's approach, and I highly recommend checking it out and reading it through.

Beyond these methodological issues, extensive model explorations for the different parameter combinations are presented. Several results are reported, but, in practice, what is then the main conclusion we could highlight here among all of them? The authors suggest that "it will be difficult to manage landscapes to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functioning simultaneously, despite their causative relationship", because, first, "increasing dispersal and interaction scales had opposing

effects" on these two patterns, and, second, unexpectedly, "ecosystems attained the highest biomass in scenarios which also led to the lowest levels of biodiversity". If these results come to be fully robust, this is, they pass all checks by other research teams trying to reproduce them using alternative approaches, we will have to accept that we should preserve biodiversity on its own rights and not because it enhances ecosystem functioning or provides particular beneficial services to humans.

References

[1] Levin, S. A. 1992. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941447

[2] Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain. 2023. Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913

[3] Baron, J. W. and Galla, T. 2020. Dispersal-induced instability in complex ecosystems. Nature Communications 11, 6032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19824-4

[4] Cushing, J. M. 1977. Integrodifferential equations and delay models in population dynamics

Springer-Verlag, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-93073-7

[5] M. A. Leibold, M. Holyoak, N. Mouquet, P. Amarasekare, J. M. Chase, M. F. Hoopes, R. D. Holt, J. B. Shurin, R. Law, D. Tilman, M. Loreau, A. Gonzalez. 2004. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters, 7(7): 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x

[6] M. Pardo-Araujo, D. García-García, D. Alonso, and F. Bartumeus. 2023. Epidemic thresholds and human mobility. Scientific reports 13 (1), 11409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38395-0

Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models

Addressing the daunting challenge of estimating species interactions from count data

Recommended by Tim Coulson and David Alonso based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTrophic interactions are at the heart of community ecology. Herbivores consume plants, predators consume herbivores, and pathogens and parasites infect, and sometimes kill, individuals of all species in a food web. Given the ubiquity of trophic interactions, it is no surprise that ecologists and evolutionary biologists strive to accurately characterize them.

The outcome of an interaction between individuals of different species depends upon numerous factors such as the age, sex, and even phenotype of the individuals involved and the environment in which they are in. Despite this complexity, biologists often simplify an interaction down to a single number, an interaction coefficient that describes the average outcome of interactions between members of the populations of the species. Models of interacting species tend to be very simple, and interaction coefficients are often estimated from time series of population sizes of interacting species. Although biologists have long known that this approach is often approximate and sometimes unsatisfactory, work on estimating interaction strengths in more complex scenarios, and using ecological data beyond estimates of abundance, is still in its infancy.

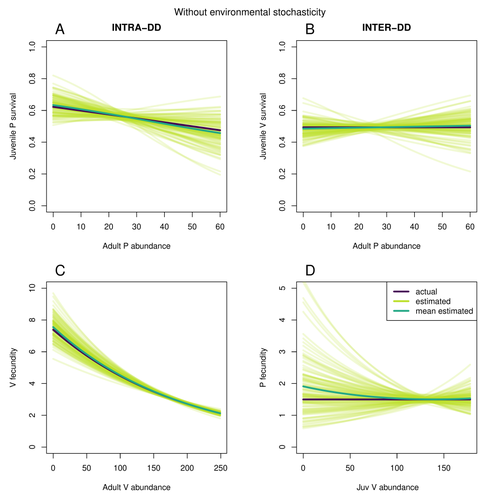

In their paper, Matthieu Paquet and Frederic Barraquand (2023) develop a demographic model of a predator and its prey. They then simulate demographic datasets that are typical of those collected by ecologists and use integrated population modelling to explore whether they can accurately retrieve the values interaction coefficients included in their model. They show that they can with good precision and accuracy. The work takes an important step in showing that accurate interaction coefficients can be estimated from the types of individual-based data that field biologists routinely collect, and it paves for future work in this area.

As if often the case with exciting papers such as this, the work opens up a number of other avenues for future research. What happens as we move from demographic models of two species interacting such as those used by Paquet and Barraquand to more realistic scenarios including multiple species? How robust is the approach to incorrectly specified process or observation models, core components of integrated population modelling that require detailed knowledge of the system under study?

Integrated population models have become a powerful and widely used tool in single-species population ecology. It is high time the techniques are extended to community ecology, and this work takes an important step in showing that this should and can be done. I would hope the paper is widely read and cited.

References

Paquet, M., & Barraquand, F. (2023). Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7W

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations

Allee effects under the magnifying glass

Recommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewerFor decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks.

However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths.

First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density.

In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner.

In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress.

References

Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169

Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084

Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007

Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868