COULSON Tim

- Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- Biodiversity, Climate change, Coexistence, Competition, Conservation biology, Demography, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Ontogeny, Population ecology, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology

- recommender, manager

Recommendations: 4

Reviews: 3

Recommendations: 4

Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models

Addressing the daunting challenge of estimating species interactions from count data

Recommended by Tim Coulson and David Alonso based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTrophic interactions are at the heart of community ecology. Herbivores consume plants, predators consume herbivores, and pathogens and parasites infect, and sometimes kill, individuals of all species in a food web. Given the ubiquity of trophic interactions, it is no surprise that ecologists and evolutionary biologists strive to accurately characterize them.

The outcome of an interaction between individuals of different species depends upon numerous factors such as the age, sex, and even phenotype of the individuals involved and the environment in which they are in. Despite this complexity, biologists often simplify an interaction down to a single number, an interaction coefficient that describes the average outcome of interactions between members of the populations of the species. Models of interacting species tend to be very simple, and interaction coefficients are often estimated from time series of population sizes of interacting species. Although biologists have long known that this approach is often approximate and sometimes unsatisfactory, work on estimating interaction strengths in more complex scenarios, and using ecological data beyond estimates of abundance, is still in its infancy.

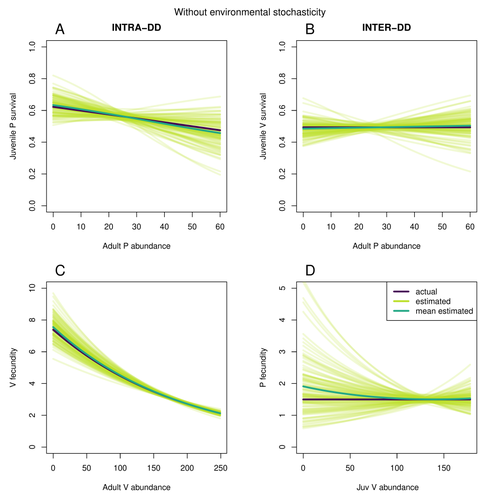

In their paper, Matthieu Paquet and Frederic Barraquand (2023) develop a demographic model of a predator and its prey. They then simulate demographic datasets that are typical of those collected by ecologists and use integrated population modelling to explore whether they can accurately retrieve the values interaction coefficients included in their model. They show that they can with good precision and accuracy. The work takes an important step in showing that accurate interaction coefficients can be estimated from the types of individual-based data that field biologists routinely collect, and it paves for future work in this area.

As if often the case with exciting papers such as this, the work opens up a number of other avenues for future research. What happens as we move from demographic models of two species interacting such as those used by Paquet and Barraquand to more realistic scenarios including multiple species? How robust is the approach to incorrectly specified process or observation models, core components of integrated population modelling that require detailed knowledge of the system under study?

Integrated population models have become a powerful and widely used tool in single-species population ecology. It is high time the techniques are extended to community ecology, and this work takes an important step in showing that this should and can be done. I would hope the paper is widely read and cited.

References

Paquet, M., & Barraquand, F. (2023). Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7W

Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach

When does seasonal reproduction evolve?

Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewerHave you ever wondered why some species breed seasonally while others do not? You might think it is all down to lattitude and the harshness of winters but it turns out it is quite a bit more complicated than that. A consequence of this is that climate change may result in the evolution of the degree of seasonal reproduction, with some species perhaps becoming less seasonal and others more so even in the same habitat.

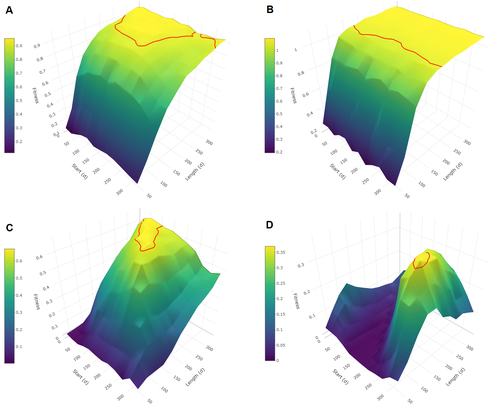

Burtschell et al. (2023) investigated how various factors influence seasonal breeding by building an individual-based model of a baboon population from which they calculated the degree of seasonality for the fittest reproductive strategy. They then altered key aspects of their model to examine how these changes impacted the degree of seasonality in the reproductive strategy. What they found is fascinating.

The degree of seasonality in reproductive strategy is expected to increase with increased seasonality in the environment, decreased food availability, increased energy expenditure, and how predictable resource availability is. Interestingly, neither female cycle length nor extrinsic infant mortality influenced the degree of seasonality in reproduction.

What this means in reality for seasonal species is more challenging to understand. Some environments appear to be becoming more seasonal yet less predictable, and some species appear to be altering their daily energy budgets in response to changing climate in quite complex ways. As with pretty much everything in biology, Burtschell et al.'s work reveals much nuance and complexity, and that predicting how species might alter their reproductive timing is fraught with challenges.

The paper is very well written. With a simpler model it may have proven possible to achieve analytical solutions, but this is a very minor gripe. The reviewers were positive about the paper, and I have little doubt it will be well-cited.

REFERENCES

Burtschell L, Dezeure J, Huchard E, Godelle B (2023) Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, 2022.08.22.504761, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761

Evolutionary emergence of alternative stable states in shallow lakes

How to evolve an alternative stable state

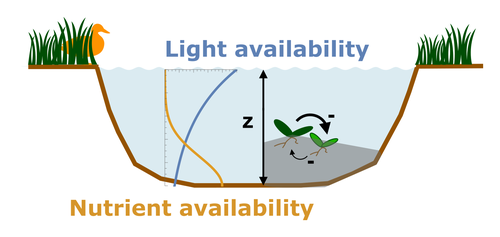

Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerAlternative stable states describe ecosystems that can persist in more than one configuration. An ecosystem can shift between stable states following some form of perturbation. There has been much work on predicting when ecosystems will shift between stable states, but less work on why some ecosystems are able to exist in alternative stable states in the first place. The paper by Ardichvili, Loeuille, and Dakos (2022) addresses this question using a simple model of a shallow lake. Their model is based on a trade-off between access to light and nutrient availability in the water column, two essential resources for the macrophytes they model. They then identify conditions when the ancestral macrophyte will diversify resulting in macrophyte species living at new depths within the lake. The authors find a range of conditions where alternative stable states can evolve, but the range is narrow. Nonetheless, their model suggests that for alternative stable states to exist, one requirement is for there to be asymmetric competition between competing species, with one species being a better competitor on one limiting resource, with the other being a better competitor on a second limiting resource.

These results are interesting and add to growing literature on how asymmetric competition can aid species coexistence. Asymmetric competition may be widespread in nature, with closely related species often being superior competitors on different resources. Incorporating asymmetric competition, and its evolution, into models does complicate theoretical investigations, but Ardichvili, Loeuille, and Dakos’ paper elegantly shows how substantial progress can be made with a model that is still (relatively) simple.

References

Ardichvili A, Loeuille N, Dakos V (2022) Evolutionary emergence of alternative stable states in shallow lakes. bioRxiv, 2022.02.23.481597, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.23.481597

Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline?

Don't jump to conclusions on arthropod abundance dynamics without appropriate data

Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Gabor L Lovei and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are dramatically modifying many aspects of our planet via increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, patterns of land-use change, and unsustainable exploitation of the planet’s resources. These changes impact the abundance of species of wild organisms, with winners and losers. Identifying how different species and groups of species are influenced by anthropogenic activity in different biomes, continents, and habitats, has become a pressing scientific question with many publications reporting analyses of disparate data on species population sizes. Many conclusions are based on the linear analysis of rather short time series of organismal abundances.

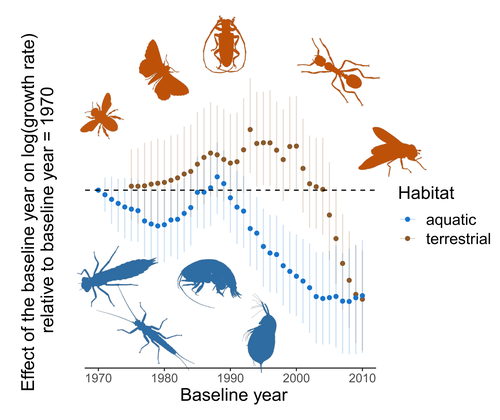

There has been particular interest in how arthropods are impacted by environmental change, with several recent papers reporting contradictory results. To investigate why these contradictions might arise, Duchenne et al. (2022) conducted an analysis of four published data sets along with a series of experimental analyses of simulated time series to examine the power of widely used statistical analyses to gain inference on temporal trends. Their important paper reveals that accurate inference on dynamics, particularly of species that exhibit large temporal fluctuations in abundance, requires time series that are substantially longer than are typically collected, as well as careful thought as to whether linear models are appropriate. Linear analyses of short time series are susceptible to providing unreliable inference as trends can be strongly influenced by points at either end of the time series.

Duchenne et al.’s paper provides important insight on the conditions when strong inference on temporal trends of arthropod (and other species) abundances can be made, and when they should be treated with caution. They do not doubt that many insect and arachnid species are changing their abundances, and that patterns in these changes may vary spatially. What their results do say is that we should treat grand claims of population recovery or rapid declines apparently to extinction with caution when they are based on short time series, particularly of species that show significant boom and bust dynamics. In many ways, these results are not unexpected, but it is nice to see such careful and thoughtful analyses and interpretation. More data are required for most arthropod species before clear assessments of abundance trends can be made. Given our reliance on many arthropods for food, pollination, and numerous ecosystem services, and the ability of other species to spread devastating human diseases such as dengue and malaria, it is advisable that we slow our modification of their habitats while additional data are collected to allow us to better characterise the trajectory of arthropod populations to understand what the consequences of our actions on the natural world are likely to be.

References

Duchenne F, Porcher E, Mihoub J-B, Loïs G, Fontaine C (2022) Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? bioRxiv, 2022.02.09.479422, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.479422

Reviews: 3

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes

A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networks

Recommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewerModelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks.

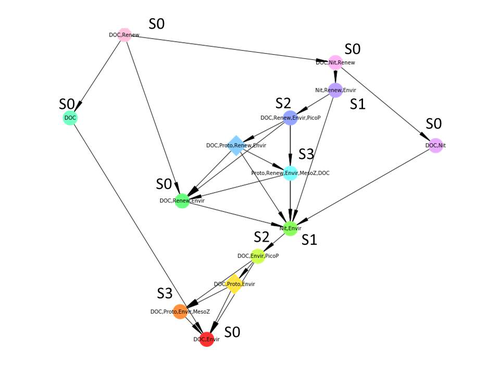

Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model.

The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed.

The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics.

Reference

Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct

Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?

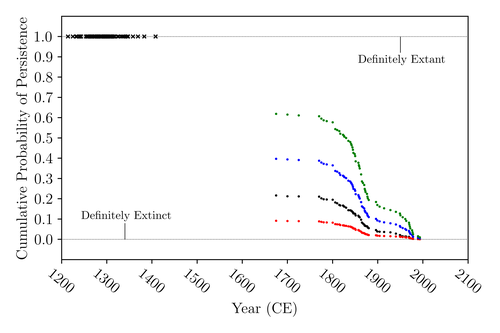

Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard HoldawayAncient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century?

The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable.

The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450.

References

Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models

A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bear

Recommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities.

Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

- the population is assumed to be closed both geographically (no immigration nor emigration) and demographically (no births nor deaths) and

- all individuals are assumed to have identical detection probabilities regardless of their individual attributes (e.g., age, body mass, social status) and habitat features (home-range location and composition) (Otis et al. 1978).

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated.

Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008.

Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

- the intraspecific home range size variation that results in individuals that move the most being most likely to be detected and

- the mortality rate which is higher on cubs than on adults and subadults (due to infanticide by males, predation, death of the mother, or abandonment).

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities.

The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References

Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x

Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007

Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135.

Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025

Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719