Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▼ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

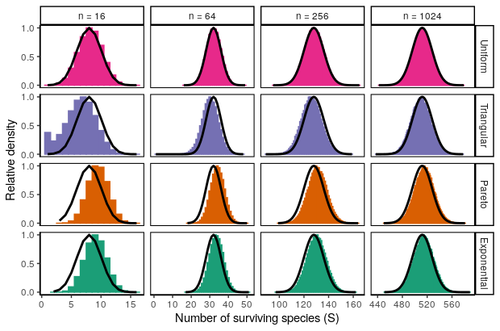

10 Aug 2023

Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-offZachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867Assembly in metacommunities driven by a competition-colonization tradeoff: more species in, more species outRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Canan Karakoç and 1 anonymous reviewerThe output of a community model depends on how you set its parameters. Thus, analyses of specific parameter settings hardwire the results to specific ecological scenarios. Because more general answers are often of interest, one tradition is to give models a statistical treatment: one summarizes how model parameters vary across species, and then predicts how changing the summary, instead of the individual parameters themselves, would change model output. Arguably the best-known example is the work initiated by May, showing that the properties of a community matrix, encoding effects species have on each other near their equilibrium, determine stability (1,2). More recently, this statistical treatment has also been applied to one of community ecology’s more prickly and slippery subjects: community assembly, which deals with the question “Given some regional species pool, which species will be able to persist together at some local ecosystem?”. Summaries of how species grow and interact in this regional pool predict the fraction of survivors and their relative abundances, the kind of dynamics, and various kinds of stability (3,4). One common characteristic of such statistical treatments is the assumption of disorder: if species do not interact in too structured ways, simple and therefore powerful predictions ensue that often stand up to scrutiny in relatively ordered systems. 2. Allesina, S. & Tang, S. (2015). The stability–complexity relationship at age 40: a random matrix perspective. Population Ecology, 57, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10144-014-0471-0 3. Bunin, G. (2016). Interaction patterns and diversity in assembled ecological communities. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.04734. 5. Miller, Z. R., Clenet, M., Libera, K. D., Massol, F. & Allesina, S. (2023). Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off. bioRxiv 2023.03.23.533867, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867 6. Serván, C. A. & Allesina, S. (2021). Tractable models of ecological assembly. Ecology Letters, 24, 1029–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13702 | Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off | Zachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina | <p>The competition-colonization trade-off is a well-studied coexistence mechanism for metacommunities. In this setting, it is believed that coexistence of all species requires their traits to satisfy restrictive conditions limiting their similarit... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Frederik De Laender | 2023-03-30 20:42:48 | View | |

12 Sep 2023

Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patternsYuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913The impact of process at different scales on diversity and ecosystem functioning: a huge challengeRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer

Scale is a big topic in ecology [1]. Environmental variation happens at particular scales. The typical scale at which organisms disperse is species-specific, but, as a first approximation, an ensemble of similar species, for instance, trees, could be considered to share a typical dispersal scale. Finally, characteristic spatial scales of species interactions are, in general, different from the typical scales of dispersal and environmental variation. Therefore, conceptually, we can distinguish these three characteristic spatial scales associated with three different processes: species selection for a given environment (E), dispersal (D), and species interactions (I), respectively. From the famous species-area relation to the spatial distribution of biomass and species richness, the different macro-ecological patterns we usually study emerge from an interplay between dispersal and local interactions in a physical environment that constrains species establishment and persistence in every location. To make things even more complicated, local environments are often modified by the species that thrive in them, which establishes feedback loops. It is usually assumed that local interactions are short-range in comparison with species dispersal, and dispersal scales are typically smaller than the scales at which the environment varies (I < D < E, see [2]), but this should not always be the case. The authors of this paper [2] relax this typical assumption and develop a theoretical framework to study how diversity and ecosystem functioning are affected by different relations between the typical scales governing interactions, dispersal, and environmental variation. This is a huge challenge. First, diversity and ecosystem functioning across space and time have been empirically characterized through a wide variety of macro-ecological patterns. Second, accommodating local interactions, dispersal and environmental variation and species environmental preferences to model spatiotemporal dynamics of full ecological communities can be done also in a lot of different ways. One can ask if the particular approach suggested by the authors is the best choice in the sense of producing robust results, this is, results that would be predicted by alternative modeling approaches and mathematical analyses [3]. The recommendation here is to read through and judge by yourself. The main unusual assumption underlying the model suggested by the authors is non-local species interactions. They introduce interaction kernels to weigh the strength of the ecological interaction with distance, which gives rise to a system of coupled integro-differential equations. This kernel is the key component that allows for control and varies the scale of ecological interactions. Although this is not new in ecology [4], and certainly has a long tradition in physics ---think about the electric or the gravity field, this approach has been widely overlooked in the development of the set of theoretical frameworks we have been using over and over again in community ecology, such as the Lotka-Volterra equations or, more recently, the metacommunity concept [5]. In Physics, classic fields have been revised to account for the fact that information cannot travel faster than light. In an analogous way, a focal individual cannot feel the presence of distant neighbors instantaneously. Therefore, non-local interactions do not exist in ecological communities. As the authors of this paper point out, they emerge in an effective way as a result of non-random movements, for instance, when individuals go regularly back and forth between environments (see [6], for an application to infectious diseases), or even migrate between regions. And, on top of this type of movement, species also tend to disperse and colonize close (or far) environments. Individual mobility and dispersal are then two types of movements, characterized by different spatial-temporal scales in general. Species dispersal, on the one hand, and individual directed movements underlying species interactions, on the other, are themselves diverse across species, but it is clear that they exist and belong to two distinct categories. In spite of the long and rich exchange between the authors' team and the reviewers, it was not finally clear (at least, to me and to one of the reviewers) whether the model for the spatio-temporal dynamics of the ecological community (see Eq (1) in [2]) is only presented as a coupled system of integro-differential equations on a continuous landscape for pedagogical reasons, but then modeled on a discrete regular grid for computational convenience. In the latter case, the system represents a regular network of local communities, becomes a system of coupled ODEs, and can be numerically integrated through the use of standard algorithms. By contrast, in the former case, the system is meant to truly represent a community that develops on continuous time and space, as in reaction-diffusion systems. In that case, one should keep in mind that numerical instabilities can arise as an artifact when integrating both local and non-local spatio-temporal systems. Spatial patterns could be then transient or simply result from these instabilities. Therefore, when analyzing spatiotemporal integro-differential equations, special attention should be paid to the use of the right numerical algorithms. The authors share all their code at https://zenodo.org/record/5543191, and all this can be checked out. In any case, the whole discussion between the authors and the reviewers has inherent value in itself, because it touches on several limitations and/or strengths of the author's approach, and I highly recommend checking it out and reading it through. Beyond these methodological issues, extensive model explorations for the different parameter combinations are presented. Several results are reported, but, in practice, what is then the main conclusion we could highlight here among all of them? The authors suggest that "it will be difficult to manage landscapes to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functioning simultaneously, despite their causative relationship", because, first, "increasing dispersal and interaction scales had opposing References [1] Levin, S. A. 1992. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941447 [2] Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain. 2023. Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913 [3] Baron, J. W. and Galla, T. 2020. Dispersal-induced instability in complex ecosystems. Nature Communications 11, 6032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19824-4 [4] Cushing, J. M. 1977. Integrodifferential equations and delay models in population dynamics [5] M. A. Leibold, M. Holyoak, N. Mouquet, P. Amarasekare, J. M. Chase, M. F. Hoopes, R. D. Holt, J. B. Shurin, R. Law, D. Tilman, M. Loreau, A. Gonzalez. 2004. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters, 7(7): 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x [6] M. Pardo-Araujo, D. García-García, D. Alonso, and F. Bartumeus. 2023. Epidemic thresholds and human mobility. Scientific reports 13 (1), 11409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38395-0 | Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns | Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain | <p style="text-align: justify;">Ecology is a science of scale, which guides our description of both ecological processes and patterns, but we lack a systematic understanding of how process scale and pattern scale are connected. Recent calls for a ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Ecosystem functioning, Landscape ecology, Theoretical ecology | David Alonso | 2021-10-13 23:24:45 | View | ||

05 Jun 2024

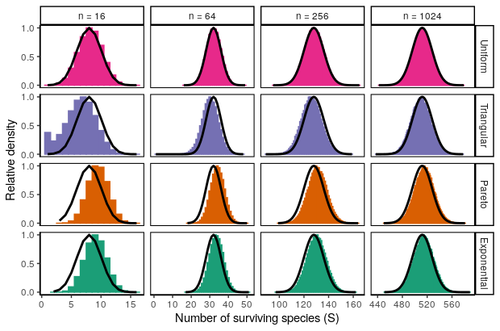

Attracting pollinators vs escaping herbivores: eco-evolutionary dynamics of plants confronted with an ecological trade-offYoussef Yacine, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.02.470900Plant-herbivore-pollinator ménage-à-trois: tell me how well they match, and I'll tell you if it's made to lastRecommended by Sylvain Billiard based on reviews by Marcos Mendez and Yaroslav Ispolatov based on reviews by Marcos Mendez and Yaroslav Ispolatov

How would a plant trait evolve if it is involved in interacting with both a pollinator and an herbivore species? The answer by Yacine and Loeuille is straightforward: it is not trivial, but it can explain many situations found in natural populations. Yacine and Loeuille applied the well-known Adaptive Dynamics framework to a system with three interacting protagonists: a herbivore, a pollinator, and a plant. The evolution of a plant trait is followed under the assumption that it regulates the frequency of interaction with the two other species. As one can imagine, that is where problems begin: interacting more with pollinators seems good, but what if at the same time it implies interacting more with herbivores? And that's not a silly idea, as there are many cases where herbivores and pollinators share the same cues to detect plants, such as colors or chemical compounds. They found that depending on the trade-off between the two types of interactions and their density-dependent effects on plant fitness, the possible joint ecological and evolutionary outcomes are numerous. When herbivory prevails, evolution can make the ménage-à-trois ecologically unstable, as one or even two species can go extinct, leaving the plant alone. Evolution can also make the coexistence of the three species more stable when pollination services prevail, or lead to the appearance of a second plant species through branching diversification of the plant trait when herbivory and pollination are balanced. Yacine and Loeuille did not only limit themselves to saying "it is possible," but they also did much work evaluating when each evolutionary outcome would occur. They numerically explored in great detail the adaptive landscape of the plant trait for a large range of parameter values. They showed that the global picture is overall robust to parameter variations, strengthening the plausibility that the evolution of a trait involved in antagonistic interactions can explain many of the correlations between plant and animal traits or phylogenies found in nature. Are we really there yet? Of course not, as some assumptions of the model certainly limit its scope. Are there really cases where plants' traits evolve much faster than herbivores' and pollinators' traits? Certainly not, but the model is so general that it can apply to any analogous system where one species is caught between a mutualistic and a predator species, including potential species that evolve much faster than the two others. And even though this limitation might cast doubt on the generality of the model's predictions, studying a system where a species' trait and a preference trait coevolve is possible, as other models have already been studied (see Fritsch et al. 2021 for a review in the case of evolution in food webs). We can bet this is the next step taken by Yacine and Loeuille in a similar framework with the same fundamental model, promising fascinating results, especially regarding the evolution of complex communities when species can accumulate after evolutionary branchings. Relaxing another assumption seems more challenging as it would certainly need to change the model itself: interacting species generally do not play fixed roles, as being mutualistic or antagonistic might generally be density-dependent (Holland and DeAngelis 2010). How would the exchange of resources between three interacting species evolve? It is an open question. References Fritsch, C., Billiard, S., & Champagnat, N. (2021). Identifying conversion efficiency as a key mechanism underlying food webs adaptive evolution: a step forward, or backward? Oikos, 130(6), 904-930. Yacine, Y., & Loeuille, N. (2024) Attracting pollinators vs escaping herbivores: eco-evolutionary dynamics of plants confronted with an ecological trade-off. bioRxiv 2021.12.02.470900; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.02.470900 | Attracting pollinators vs escaping herbivores: eco-evolutionary dynamics of plants confronted with an ecological trade-off | Youssef Yacine, Nicolas Loeuille | <p style="text-align: justify;">Many plant traits are subject to an ecological trade-off between attracting pollinators and escaping herbivores. The interplay of both plant-animal interaction types determines their evolution. As most studies focus... |  | Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Herbivory, Pollination, Theoretical ecology | Sylvain Billiard | 2023-03-21 14:23:12 | View | |

12 May 2022

Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapesYasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fujaco, Mariangela Garcia Praca Leite, Joice Paiva Vidigal Martins, Graziella Franca Monteiro, Rodolfo Dirzo https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375Complex but positive diversity - ecosystem functioning relationships in Riparian tropical forestsRecommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many ecological drivers can impact ecosystem functionality and multifunctionality, with the latter describing the joint impact of different functions on ecosystem performance and services. It is now generally accepted that taxonomically richer ecosystems are better able to sustain high aggregate functionality measures, like energy transfer, productivity or carbon storage (Buzhdygan 2020, Naeem et al. 2009), and different ecosystem services (Marselle et al. 2021) than those that are less rich. Antonini et al. (2022) analysed an impressive dataset on animal and plant richness of tropical riparian forests and abundances, together with data on key soil parameters. Their work highlights the importance of biodiversity on functioning, while accounting for a manifold of potentially covarying drivers. Although the key result might not come as a surprise, it is a useful contribution to the diversity - ecosystem functioning topic, because it is underpinned with data from tropical habitats. To date, most analyses have focused on temperate habitats, using data often obtained from controlled experiments. The paper also highlights that diversity–functioning relationships are complicated. Drivers of functionality vary from site to site and each measure of functioning, including parameters as demonstrated here, can be influenced by very different sets of predictors, often associated with taxonomic and trait diversity. Single correlative comparisons of certain aspects of diversity and functionality might therefore return very different results. Antonini et al. (2022) show that, in general, using 22 predictors of functional diversity, varying predictor subsets were positively associated with soil functioning. Correlational analyses alone cannot resolve the question of causal link. Future studies should therefore focus on inferring precise mechanisms behind the observed relationships, and the environmental constraints on predictor subset composition and strength. References Antonini Y, Beirão MV, Costa FV, Azevedo CS, Wojakowski MM, Kozovits AR, Pires MRS, Sousa HC de, Messias MCTB, Fujaco MA, Leite MGP, Vidigal JP, Monteiro GF, Dirzo R (2022) Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2021.09.08.459375, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375 Buzhdygan OY, Meyer ST, Weisser WW, Eisenhauer N, Ebeling A, Borrett SR, Buchmann N, Cortois R, De Deyn GB, de Kroon H, Gleixner G, Hertzog LR, Hines J, Lange M, Mommer L, Ravenek J, Scherber C, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Scheu S, Schmid B, Steinauer K, Strecker T, Tietjen B, Vogel A, Weigelt A, Petermann JS (2020) Biodiversity increases multitrophic energy use efficiency, flow and storage in grasslands. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1123-8 Marselle MR, Hartig T, Cox DTC, de Bell S, Knapp S, Lindley S, Triguero-Mas M, Böhning-Gaese K, Braubach M, Cook PA, de Vries S, Heintz-Buschart A, Hofmann M, Irvine KN, Kabisch N, Kolek F, Kraemer R, Markevych I, Martens D, Müller R, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Potts JM, Stadler J, Walton S, Warber SL, Bonn A (2021) Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International, 150, 106420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106420 Naeem S, Bunker DE, Hector A, Loreau M, Perrings C (Eds.) (2009) Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning, and Human Wellbeing: An Ecological and Economic Perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199547951.001.0001 | Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes | Yasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fuja... | <ol> <li style="text-align: justify;">Restoration of tropical riparian forests is challenging, since these ecosystems are the most diverse, dynamic, and complex physical and biological terrestrial habitats. This study tested whether biodiversity ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecological successions, Ecosystem functioning, Terrestrial ecology | Werner Ulrich | 2021-09-10 10:51:23 | View | |

27 Nov 2023

Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted TreesWilliam Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443Gradient Boosted Trees can deliver more than accurate ecological predictionsRecommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne diseases are an important burden on public health all over the globe, making accurate forecasts of tick population a key ingredient in a successful public health strategy. Over long time scales, tick populations can undergo complex dynamics, as they are sensitive to many non-linear effects due to the complex relationships between ticks and the relevant (numerical) features of their environment. But luckily, capturing complex non-linear responses is a task that machine learning thrives on. In this contribution, Manley et al. (2023) explore the use of Gradient Boosted Trees to predict the distribution (presence/absence) and abundance of ticks across New York state. This is an interesting modelling challenge in and of itself, as it looks at the same ecological question as an instance of a classification problem (presence/absence) or of a regression problem (abundance). In using the same family of algorithm for both, Manley et al. (2023) provide an interesting showcase of the versatility of these techniques. But their article goes one step further, by setting up a multi-class categorical model that estimates jointly the presence and abundance of a population. I found this part of the article particularly elegant, as it provides an intermediate modelling strategy, in between having two disconnected models for distribution and abundance, and having nested models where abundance is only predicted for the present class (see e.g. Boulangeat et al., 2012, for a great description of the later). One thing that Manley et al. (2023) should be commended for is their focus on opening up the black box of machine learning techniques. I have never believed that ML models are more inherently opaque than other families of models, but the focus in this article on explainable machine learning shows how these models might, in fact, bring us closer to a phenomenological understanding of the mechanisms underpinning our observations. There is also an interesting discussion in this article, on the rate of false negatives in the different models that are being benchmarked. Although model selection often comes down to optimizing the overall quality of the confusion matrix (for distribution models, anyway), depending on the type of information we seek to extract from the model, not all types of errors are created equal. If the purpose of the model is to guide actions to control vectors of human pathogens, a false negative (predicting that the vector is absent at a site where it is actually present) is a potentially more damaging outcome, as it can lead to the vector population (and therefore, potentially, transmission) increasing unchecked. References

Boulangeat I, Gravel D, Thuiller W. Accounting for dispersal and biotic interactions to disentangle the drivers of species distributions and their abundances: The role of dispersal and biotic interactions in explaining species distributions and abundances. Ecol Lett. 2012;15: 584-593. Manley W, Tran T, Prusinski M, Brisson D. (2023) Modeling tick populations: An ecological test case for gradient boosted trees. bioRxiv, 2023.03.13.532443, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443 | Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted Trees | William Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">General linear models have been the foundational statistical framework used to discover the ecological processes that explain the distribution and abundance of natural populations. Analyses of the rapidly expanding ... | Parasitology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Timothée Poisot | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2023-03-23 23:41:17 | View | |

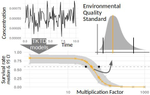

14 Dec 2018

Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics modelsVirgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles https://doi.org/10.1101/356469Addressing uncertainty in Environmental Risk Assessment using mechanistic toxicological models coupled with Bayesian inferenceRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Andreas Focks and 2 anonymous reviewersEnvironmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a strategic conceptual framework to characterize the nature and magnitude of risks, to humans and biodiversity, of the release of chemical contaminants in the environment. Several measures have been suggested to enhance the science and application of ERA, including the identification and acknowledgment of uncertainties that potentially influence the outcome of risk assessments, and the appropriate consideration of temporal scale and its linkage to assessment endpoints [1]. References [1] Dale, V. H., Biddinger, G. R., Newman, M. C., Oris, J. T., Suter, G. W., Thompson, T., ... & Chapman, P. M. (2008). Enhancing the ecological risk assessment process. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 4(3), 306-313. doi: 10.1897/IEAM_2007-066.1 | Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models | Virgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles | <p>Providing reliable environmental quality standards (EQS) is a challenging issue for environmental risk assessment (ERA). These EQS are derived from toxicity endpoints estimated from dose-response models to identify and characterize the environm... |  | Chemical ecology, Ecotoxicology, Experimental ecology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2018-06-27 21:33:30 | View | |

02 Oct 2018

How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion.Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard 10.1101/273557Optimal foraging in a changing world: old questions, new perspectivesRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer

Marginal value theorem (MVT) is an archetypal model discussed in every behavioural ecology textbook. Its popularity is largely explained but the fact that it is possible to solve it graphically (at least in its simplest form) with the minimal amount of equations, which is a sensible strategy for an introductory course in behavioural ecology [1]. Apart from this heuristic value, one may be tempted to disregard it as a naive toy model. After a burst of interest in the 70's and the 80's, the once vivid literature about optimal foraging theory (OFT) has lost its momentum [2]. Yet, OFT and MVT have remained an active field of research in the parasitoidologists community, mostly because the sampling strategy of a parasitoid in patches of hosts and its resulting fitness gain are straightforward to evaluate, which eases both experimental and theoretical investigations [3]. References [1] Fawcett, T. W. & Higginson, A. D. 2012 Heavy use of equations impedes communication among biologists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 11735–11739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205259109 | How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion. | Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard | The Marginal Value Theorem (MVT) provides a framework to predict how habitat modifications related to the distribution of resources over patches should impact the realized fitness of individuals and their optimal rate of movement (or patch residen... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2018-03-05 10:42:11 | View | |

05 Apr 2019

Using a large-scale biodiversity monitoring dataset to test the effectiveness of protected areas at conserving North-American breeding birdsVictor Cazalis, Soumaya Belghali, Ana S.L. Rodrigues https://doi.org/10.1101/433037Protected Areas effects on biodiversity: a test using bird data that hopefully will give ideas for much more studies to comeRecommended by Paul Caplat based on reviews by Willson Gaul and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the face of worldwide declines in biodiversity, evaluating the effectiveness of conservation practices is an absolute necessity. Protected Areas (PA) are a key tool for conservation, and the question “Are PA effective” has been on many a research agenda, as the introduction to this preprint will no doubt convince you. A challenge we face is that, until now, few studies have been explicitly designed to evaluate PA, and despite the rise of meta-analyses on the topic, our capacity to quantify their effect on biodiversity remains limited. References [1] Cazalis, V., Belghali, S., & Rodrigues, A. S. (2019). Using a large-scale biodiversity monitoring dataset to test the effectiveness of protected areas at conserving North-American breeding birds. bioRxiv, 433037, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/433037 | Using a large-scale biodiversity monitoring dataset to test the effectiveness of protected areas at conserving North-American breeding birds | Victor Cazalis, Soumaya Belghali, Ana S.L. Rodrigues | <p>Protected areas currently cover about 15% of the global land area, and constitute one of the main tools in biodiversity conservation. Quantifying their effectiveness at protecting species from local decline or extinction involves comparing prot... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Macroecology | Paul Caplat | 2018-10-04 08:43:34 | View | |

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

29 May 2023

Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean SeaValentin Lauret, Hélène Labach, Léa David, Matthieu Authier, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/npd6uMapping co-occurence of human activities and wildlife from multiple data sourcesRecommended by Paul Caplat based on reviews by Mason Fidino and 1 anonymous reviewerTwo fields of research have grown considerably over the past twenty years: the investigation of human-wildlife conflicts (e.g. see Treves & Santiago-Ávila 2020), and multispecies occupancy modelling (Devarajan et al. 2020). In their recent study, Lauret et al. (2023) combined both in an elegant methodological framework, applied to the study of the co-occurrence of fishing activities and bottlenose dolphins in the French Mediterranean. A common issue with human-wildlife conflicts (and, in particular, fishery by-catch) is that data is often only available from those conflicts or interactions, limiting the validity of the predictions (Kuiper et al. 2022). Lauret et al. use independent data sources informing the occurrence of fishing vessels and dolphins, combined in a Bayesian multispecies occupancy model where vessels are "the other species". I particularly enjoyed that approach, as integration of human activities in ecological models can be extremely complex, but can also translate in phenomena that can be captured as one would of individuals of a species, as long as the assumptions are made clearly. Here, the model is made more interesting by accounting for environmental factors (seabed depth) borrowing an approach from Generalized Additive Models in the Bayesian framework. While not pretending to provide (yet) practical recommendations to help conserve bottlenose dolphins (and other wildlife conflicts), this study and the associated code are a promising step in that direction. REFERENCES Devarajan, K., Morelli, T.L. & Tenan, S. (2020), Multi-species occupancy models: review, roadmap, and recommendations. Ecography, 43: 1612-1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04957 Kuiper, T., Loveridge, A.J. and Macdonald, D.W. (2022), Robust mapping of human–wildlife conflict: controlling for livestock distribution in carnivore depredation models. Anim. Conserv., 25: 195-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12730 Lauret V, Labach H, David L, Authier M, & Gimenez O (2023) Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean Sea. Ecoevoarxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/npd6u Treves, A. & Santiago-Ávila, F.J. (2020). Myths and assumptions about human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 34, 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13472 | Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean Sea | Valentin Lauret, Hélène Labach, Léa David, Matthieu Authier, Olivier Gimenez | <p style="text-align: justify;">In the Mediterranean Sea, interactions between marine species and human activities are prevalent. The coastal distribution of bottlenose dolphins (<em>Tursiops truncatus</em>) and the predation pressure they put on ... |  | Marine ecology, Population ecology, Species distributions | Paul Caplat | 2022-10-21 11:13:36 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle