Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Dec 2019

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslandsNatasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2543768The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradientRecommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure. References [1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press. | Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands | Natasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol | <p>For plant-pollinator interactions to occur, the flowering of plants and the flying period of pollinators (i.e. their phenologies) have to overlap. Yet, few models make use of this principle to predict interactions and fewer still are able to co... |  | Interaction networks, Pollination, Statistical ecology | Anna Eklöf | 2019-01-18 19:02:13 | View | |

14 Jul 2023

Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlandsMallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780Searching for conservation opportunities at the marginsRecommended by Ana S. L. Rodrigues based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción

In a progressively human-dominated planet (Venter et al., 2016), the fate of many species will depend on the extent to which they can persist in anthropogenic landscapes. In Western Europe, where only small areas of primary habitat remain (e.g. Sabatini et al., 2018), semi-natural areas are crucial habitats to many native species, yet they are threatened by the expansion of human activities, including agricultural expansion and intensification (Rigal et al., 2023). A new study by Mallet and colleagues (Mallet et al., 2023) investigates the extent to which bird species in the Camargue region are able to use the margins of agricultural fields as substitutes for their preferred semi-natural habitats. Located in the delta of the Rhône River in Southern France, the Camargue is internationally recognized for its biodiversity value, classified as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO and as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention (IUCN & UN-WCMC, 2023). Mallet and colleagues tested three specific hypotheses: that grass strips (grassy field boundaries, including grassy tracks or dirt roads used for moving agricultural machinery) can function as substitute habitats for grassland species; that reed strips along drainage ditches (common in the rice paddy landscapes of the Camargue) can function as substitute habitats to wetland species; and that hedgerows can function as substitute habitats to species that favour woodland edges. They did so by measuring how the local abundances of 14 bird species (nine typical of forest edges, 3 of grasslands, and two of reedbeds) respond to increasing coverage of either the three types of field margins or of the three types of semi-natural habitat. This is an elegant study design, yet – as is often the case with real field data – results are not as simple as expected. Indeed, for most species (11 out of 14) local abundances did not increase significantly with the area of their supposed primary habitat, undermining the assumption that they are strongly associated with (or dependent on) those habitats. Among the three species that did respond positively to the area of their primary habitat, one (a forest edge species) responded positively but not significantly to the area of field margins (hedgerows), providing weak evidence to the habitat compensation hypothesis. For the other two (grassland and a wetland species), abundance responded even more strongly to the area of field margins (grass and reed strips, respectively) than to the primary habitat, suggesting that the field margins are not so much a substitute but valuable habitats in their own right. It would have been good conservation news if field margins were found to be suitable habitat substitutes to semi-natural habitats, or at least reasonable approximations, to most species. Given that these margins have functional roles in agricultural landscapes (marking boundaries, access areas, water drainage), they could constitute good win-win solutions for reconciling biodiversity conservation with agricultural production. Alas, the results are more complicated than that, with wide variation in species responses that could not have been predicted from presumed habitat affinities. These results illustrate the challenges of conservation practice in complex landscapes formed by mosaics of variable land use types. With species not necessarily falling neatly into habitat guilds, it becomes even more challenging to plan strategically how to manage landscapes to optimize their conservation. The results presented here suggest that species’ abundances may be responding to landscape variables not taken into account in the analyses, such as connectivity between habitat patches, or maybe positive and negative edge effects between land use types. That such uncertainties remain even in a well-studied region as the Camargue, and for such a well-studied taxon such as birds, only demonstrates the continued importance of rigorous field studies testing explicit hypotheses such as this one by Mallet and colleagues. References IUCN, & UN-WCMC (2023). Protected Planet. Protected Planet. https://www.protectedplanet.net/en Mallet, P., Béchet, A., Sirami, C., Mesléard, F., Blanchon, T., Calatayud, F., Dagonet, T., Gaget, E., Leray, C., & Galewski, T. (2023). Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490780, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780 Rigal, S., Dakos, V., Alonso, H., Auniņš, A., Benkő, Z., Brotons, L., Chodkiewicz, T., Chylarecki, P., de Carli, E., del Moral, J. C. et al. (2023). Farmland practices are driving bird population decline across Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120, e2216573120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216573120 Sabatini, F. M., Burrascano, S., Keeton, W. S., Levers, C., Lindner, M., Pötzschner, F., Verkerk, P. J., Bauhus, J., Buchwald, E., Chaskovsky, O., Debaive, N. et al. (2018). Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Diversity and Distributions, 24, 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12778 Venter, O., Sanderson, E. W., Magrach, A., Allan, J. R., Beher, J., Jones, K. R., Possingham, H. P., Laurance, W. F., Wood, P., Fekete, B. M., Levy, M. A., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nature Communications, 7, 12558. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12558 | Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands | Mallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding birds in agricultural landscapes have declined considerably since the 1950s and the beginning of agricultural intensification in Europe. Given the increasing pressure on agricultural land, it is necessary t... | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Landscape ecology | Ana S. L. Rodrigues | 2022-05-09 10:48:49 | View | ||

11 Aug 2023

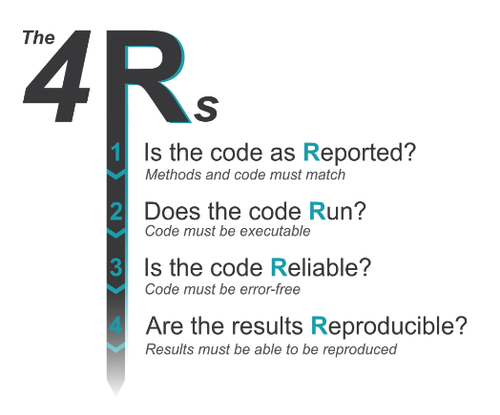

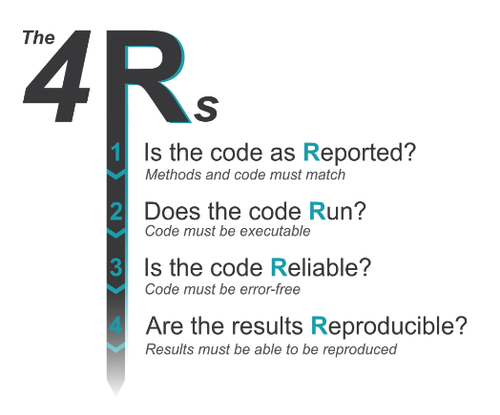

Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary BiologyEdward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64A handy “How to” review code for ecologists and evolutionary biologistsRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewer

Ivimey Cook et al. (2023) provide a concise and useful “How to” review code for researchers in the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology, where the systematic review of code is not yet standard practice during the peer review of articles. Consequently, this article is full of tips for authors on how to make their code easier to review. This handy article applies not only to ecology and evolutionary biology, but to many fields that are learning how to make code more reproducible and shareable. Taking this step toward transparency is key to improving research rigor (Brito et al. 2020) and is a necessary step in helping make research trustable by the public (Rosman et al. 2022). References Brito, J. J., Li, J., Moore, J. H., Greene, C. S., Nogoy, N. A., Garmire, L. X., & Mangul, S. (2020). Recommendations to enhance rigor and reproducibility in biomedical research. GigaScience, 9(6), giaa056. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa056 Ivimey-Cook, E. R., Pick, J. L., Bairos-Novak, K., Culina, A., Gould, E., Grainger, M., Marshall, B., Moreau, D., Paquet, M., Royauté, R., Sanchez-Tojar, A., Silva, I., Windecker, S. (2023). Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. EcoEvoRxiv, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64 Rosman, T., Bosnjak, M., Silber, H., Koßmann, J., & Heycke, T. (2022). Open science and public trust in science: Results from two studies. Public Understanding of Science, 31(8), 1046-1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221100686 | Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Edward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker | <p>Code review increases reliability and improves reproducibility of research. As such, code review is an inevitable step in software development and is common in fields such as computer science. However, despite its importance, code review is not... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology | Corina Logan | 2023-05-19 15:54:01 | View | |

18 Mar 2019

Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasiteAmalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2592114Limited dispersal in a vector on territorial hostsRecommended by Adele Mennerat based on reviews by Shelly Lachish and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitism requires parasites and hosts to meet and is therefore conditioned by their respective dispersal abilities. While dispersal has been studied in a number of wild vertebrates (including in relation to infection risk), we still have poor knowledge of the movements of their parasites. Yet we know that many parasites, and in particular vectors transmitting pathogens from host to host, possess the ability to move actively during at least part of their lives. References | Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasite | Amalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy | <p>Functional dispersal (between-site movement, with or without subsequent reproduction) is a key trait acting on the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of a species, with potential cascading effects on other members of the local community. ... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Epidemiology, Parasitology, Population ecology | Adele Mennerat | 2018-11-05 11:44:58 | View | |

03 Jan 2024

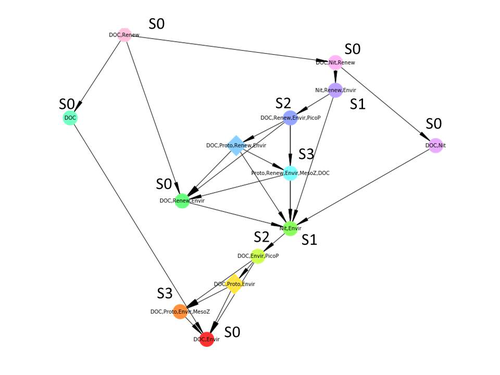

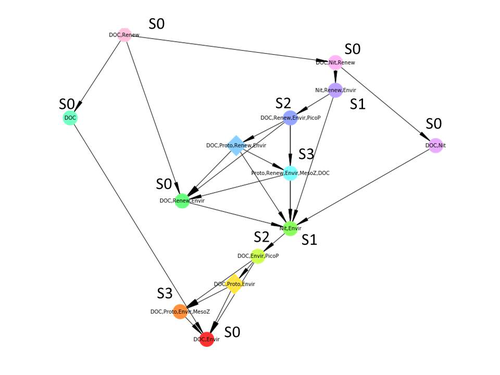

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changesCedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networksRecommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewerModelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks. Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model. The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed. The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics. Reference Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055 | Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes | Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy | <p>Trophic interaction networks are notoriously difficult to understand and to diagnose (i.e., to identify contrasted network functioning regimes). Such ecological networks have many direct and indirect connections between species, and these conne... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Interaction networks, Microbial ecology & microbiology | Francis Raoul | Tim Coulson | 2023-07-03 10:42:34 | View |

01 Jun 2018

Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecologyTimothée Poisot, Richard Labrie, Erin Larson, Anastasia Rahlin 10.1101/150128Some thoughts on computational ecology from people who I’m sure use different passwords for each of their accountsRecommended by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko based on reviews by Matthieu Barbier and 1 anonymous reviewerAre you an ecologist who uses a computer or know someone that does? Even if your research doesn’t rely heavily on advanced computational techniques, it likely hasn’t escaped your attention that computers are increasingly being used to analyse field data and make predictions about the consequences of environmental change. So before artificial intelligence and robots take over from scientists, now is great time to read about how experts think computers could make your life easier and lead to innovations in ecological research. In “Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology”, Poisot and colleagues [1] provide a brief history of computational ecology and offer their thoughts on how computational thinking can help to bridge different types of ecological knowledge. In this wide-ranging article, the authors share practical strategies for realising three main goals: (i) tighter integration of data and models to make predictions that motivate action by practitioners and policy-makers; (ii) closer interaction between data-collectors and data-users; and (iii) enthusiasm and aptitude for computational techniques in future generations of ecologists. The key, Poisot and colleagues argue, is for ecologists to “engage in meaningful dialogue across disciplines, and recognize the currencies of their collaborations.” Yes, this is easier said than done. However, the journey is much easier with a guide and when everyone involved serves to benefit not only from the eventual outcome, but also the process. References [1] Poisot, T., Labrie, R., Larson, E., & Rahlin, A. (2018). Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology. BioRxiv, 150128, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/150128 | Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology | Timothée Poisot, Richard Labrie, Erin Larson, Anastasia Rahlin | Computational ecology, defined as the application of computational thinking to ecological problems, has the potential to transform the way ecologists think about the integration of data and models. As the practice is gaining prominence as a way to... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Phillip P.A. Staniczenko | 2018-02-05 20:51:41 | View | |

20 Jun 2024

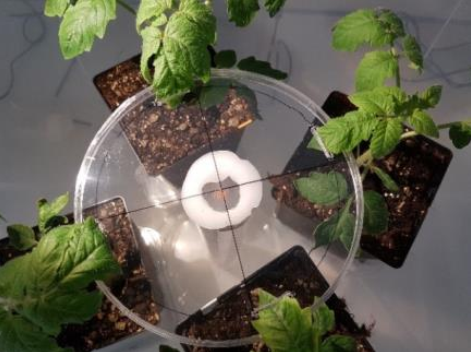

Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitorsDiogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707We are better together: Spider mites running away from Cadmium contaminated plants make better decisions collectively than individuallyRecommended by Ruben Heleno based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Hyperaccumulator plants can concentrate heavy metals present on the soil in their tissues, avoiding their toxic effects and potentially discouraging herbivores (Martens & Boyd, 1994). But not all herbivores are necessarily discouraged, and access to locally abundant resources with low interspecific competition from other herbivores, can affect feeding choices. Godinho et al. performed a series of controlled laboratorial trials to evaluate if herbivores (spider mites) avoid tomato plants with high concentrations of Cadmium under alternative scenarios, namely: the presence/absence of conspecifics, the presence/absence of a competitor species (a congeneric mite), and the relative abundance of contaminated plants. They found that when looking for plants to lay their eggs, individual spider-mites (females) do not seem to discriminate between plants with or without cadmium, despite a significantly lower performance on the former. However, they consistently chose plants without Cadmium in set-ups where 200 mites are faced with this decision together. This preference was consistent and independent from the relative abundance of cadmium-free plants, but only when mites do this decision collectively. In addition, this preference was stronger than that for plants where interspecific competition was lower, with mites preferring to face high competition from congeneric herbivores than laying their eggs on Cadmium contaminated plants. Taken together these experiments suggest that aggregation is a key mechanism by which spider mites can avoid metal contaminated plants. As good research often does, these experiments open several important questions that will need to be addressed in the future. In particular, it will be important to clarify what are the sensorial and behavioural mechanisms that allow this decision/outcome when spider mites make this choice collectively but lead to a different outcome (no choice) when they face this decision alone. Additionally, it will be interesting to explore the potentially adaptive (or non-adaptive) consequences of this behaviour in terms of individual and inclusive fitness. One thing seems certain: both the abiotic and the biotic context can affect spider mite choices, and both need to be considered to advance our understanding about the trade-offs between plant defence mechanisms and associated herbivore decisions and fitness. References Martens, S. N., & Boyd, R. S. (1994). The ecological significance of nickel hyperaccumulation: a plant chemical defense. Oecologia, 98(3–4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00324227 Godinho, D. P., I. Fragata, M. C. de la Masseliere, S. Magalhaes 2024 Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors. bioRxiv, ver. 4, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology 2023.08.17.553707. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707

| Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors | Diogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes | <p>1. Plants can accumulate heavy metals from polluted soils on their shoots and use this to defend themselves against herbivory. One possible strategy for herbivores to cope with the reduction in performance imposed by heavy metal accumulation in... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Competition, Habitat selection, Herbivory | Ruben Heleno | 2023-11-09 11:52:58 | View | |

23 Oct 2023

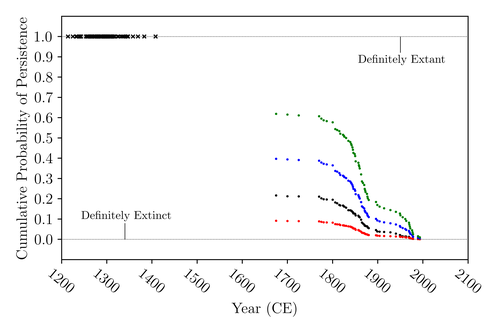

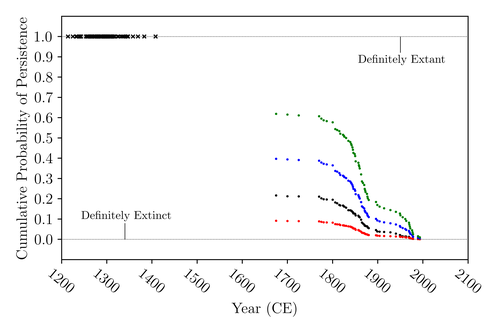

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

16 Jun 2023

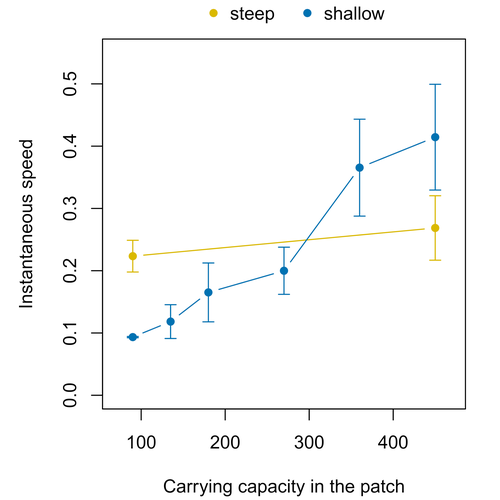

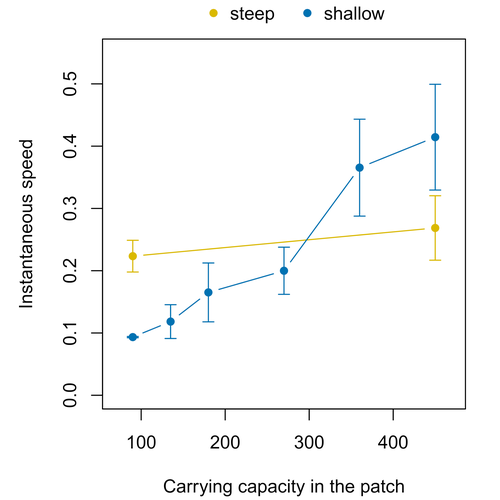

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansionThibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environmentsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Dispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007). Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients). Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011). The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions. REFERENCES Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746 Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1 Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431. Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255 Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107 Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x | Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion | Thibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken | <p>Demographic processes that occur at the local level, such as positive density dependence in growth or dispersal, are known to shape population range expansion, notably by linking carrying capacity to invasion speed. As a result of these process... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Joaquín Hortal | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-11-16 15:52:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle