Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

14 Jan 2021

Consistent variations in personality traits and their potential for genetic improvement of biocontrol agents: Trichogramma evanescens as a case studySilène Lartigue, Myriam Yalaoui, Jean Belliard, Claire Caravel, Louise Jeandroz, Géraldine Groussier, Vincent Calcagno, Philippe Louâpre, François-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Thibaut Malausa and Jérôme Moreau https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.257881Tell us how you can be, and we’ll make you better: exploiting genetic variability in personality traits to improve top-down control of agricultural pestsRecommended by Marta Montserrat based on reviews by Bart A Pannebakker, François Dumont, Joshua Patrick Byrne and Ana Pimenta Goncalves PereiraAgriculture in the XXI century faces the huge challenge of having to provide food to a rapidly growing human population, which is expected to reach 10.9 billion in 2100 (UUNN 2019), by means of practices and methods that guarantee crop sustainability, human health safety, and respect to the environment (UUNN 2015). Such regulation by the United Nations ultimately entails that agricultural scientists are urged to design strategies and methods that effectively minimize the use of harmful chemical products to control pest populations and to improve soil quality. References Bielza, P., Balanza, V., Cifuentes, D. and Mendoza, J. E. (2020). Challenges facing arthropod biological control: Identifying traits for genetic improvement of predators in protected crops. Pest Manag Sci. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5857 | Consistent variations in personality traits and their potential for genetic improvement of biocontrol agents: Trichogramma evanescens as a case study | Silène Lartigue, Myriam Yalaoui, Jean Belliard, Claire Caravel, Louise Jeandroz, Géraldine Groussier, Vincent Calcagno, Philippe Louâpre, François-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Thibaut Malausa and Jérôme Moreau | <p>Improvements in the biological control of agricultural pests require improvements in the phenotyping methods used by practitioners to select efficient biological control agent (BCA) populations in industrial rearing or field conditions. Consist... | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biological control, Evolutionary ecology, Life history | Marta Montserrat | 2020-08-24 10:40:03 | View | ||

07 Oct 2019

Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities?Antoine Gardarin and Muriel Valantin-Morison https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3468920On the importance of experimental design: pitfall traps and arthropod communitiesRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cécile ALBERT and Matthias Foellmer based on reviews by Cécile ALBERT and Matthias Foellmer

Despite the increasing refinement of statistical methods, a robust experimental design is still one of the most important cornerstones to answer ecological and evolutionary questions. However, there is a strong trade-off between a perfect design and its feasibility. A common mantra is that more data is always better, but how much is enough is complex to answer, specially when we want to capture the spatial and temporal variability of a given process. Gardarin and Valantin-Morison [1] make an effort to answer these questions for a practical case: How many pitfalls traps, of which type, and over which extent, do we need to detect shifts in arthropod community composition in agricultural landscapes. There is extense literature on how to approach these challenges using preliminary data in combination with simulation methods [e.g. 2], but practical cases are always welcomed to illustrate the complexity of the decisions to be made. A key challenge in this situation is the nature of simplified and patchy agricultural arthropod communities. In this context, small effect sizes are expected, but those small effects are relevant from an ecological point of view because small increases at low biodiversity may produce large gains in ecosystem functioning [3]. References [1] Gardarin, A. and Valantin-Morison, M. (2019). Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities? Zenodo, 3468920, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3468920 | Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities? | Antoine Gardarin and Muriel Valantin-Morison | <p>1. Ground dwelling arthropods are affected by agricultural practices, and analyses of their responses to different crop management are required. The sampling efficiency of pitfall traps has been widely studied in natural ecosystems. In arable a... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Biological control, Community ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2019-01-08 09:40:14 | View | |

20 Feb 2024

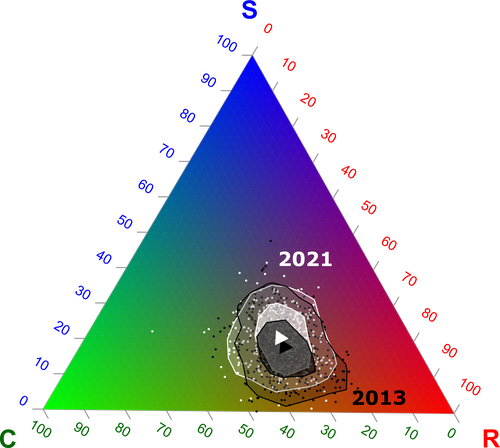

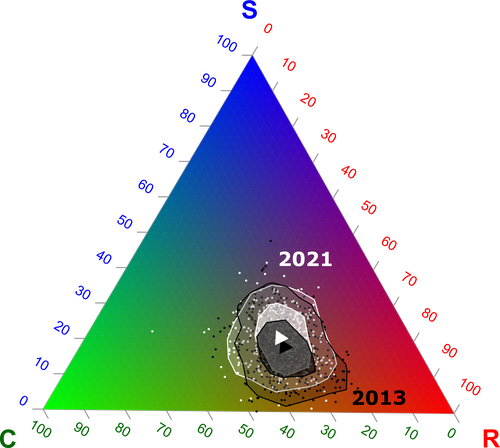

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practicesIsis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persistRecommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich

Agricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ. References Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013 Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2 Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005 Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244 Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14 Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain. Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003 Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956 Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715 | Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices | Isis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried | <p style="text-align: justify;">Over the past decades, agricultural intensification and climate change have led to vegetation shifts. However, functional trade-offs linking traits responding to climate and farming practices are rarely analyzed, es... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Climate change, Community ecology | Julia Astegiano | 2023-03-04 15:40:35 | View | |

17 Mar 2021

Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslandsCatherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137Resolving herbivore influences under climate variabilityRecommended by Jennifer Krumins based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersWe know that herbivory can have profound influences on plant communities with respect to their distribution and productivity (recently reviewed by Jia et al. 2018). However, the degree to which these effects are realized belowground in the rhizosphere is far less understood. Indeed, many independent studies and synthesis find that the environmental context can be more important than the direct effects of herbivore activity and its removal of plant biomass (Andriuzzi and Wall 2017, Schrama et al. 2013). In spite of dedicated attention, generalizable conclusions remain a bit elusive (Sitters and Venterink 2015). Picon-Cochard and colleagues (2021) help address this research conundrum in an elegant analysis that demonstrates the interaction between long-term cattle grazing and climatic variability on primary production aboveground and belowground. Over the course of two years, Picon-Cochard et al. (2021) measured above and belowground net primary productivity in French grasslands that had been subject to ten years of managed cattle grazing. When they compared these data with climatic trends, they find an interesting interaction among grazing intensity and climatic factors influencing plant growth. In short, and as expected, plants allocate more resources to root growth in dry years and more to above ground biomass in wet and cooler years. However, this study reveals the degree to which this is affected by cattle grazing. Grazed grasslands support warmer and dryer soils creating feedback that further and significantly promotes root growth over green biomass production. The implications of this work to understanding the capacity of grassland soils to store carbon is profound. This study addresses one brief moment in time of the long trajectory of this grazed ecosystem. The legacy of grazing does not appear to influence soil ecosystem functioning with respect to root growth except within the environmental context, in this case, climate. This supports the notion that long-term research in animal husbandry and grazing effects on landscapes is deeded. It is my hope that this study is one of many that can be used to synthesize many different data sets and build a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of grazing and herd management within the context of a changing climate. Herbivory has a profound influence upon ecosystem health and the distribution of plant communities (Speed and Austrheim 2017), global carbon storage (Chen and Frank 2020) and nutrient cycling (Sitters et al. 2020). The analysis and results presented by Picon-Cochard (2021) help to resolve the mechanisms that underly these complex effects and ultimately make projections for the future. References Andriuzzi WS, Wall DH. 2017. Responses of belowground communities to large aboveground herbivores: Meta‐analysis reveals biome‐dependent patterns and critical research gaps. Global Change Biology 23:3857-3868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13675 Chen J, Frank DA. 2020. Herbivores stimulate respiration from labile and recalcitrant soil carbon pools in grasslands of Yellowstone National Park. Land Degradation & Development 31:2620-2634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3656 Jia S, Wang X, Yuan Z, Lin F, Ye J, Hao Z, Luskin MS. 2018. Global signal of top-down control of terrestrial plant communities by herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6237-6242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707984115 Picon-Cochard C, Vassal N, Martin R, Herfurth D, Note P, Louault F. 2021. Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands. bioRxiv, 2020.08.23.263137, version 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137 Schrama M, Veen GC, Bakker EL, Ruifrok JL, Bakker JP, Olff H. 2013. An integrated perspective to explain nitrogen mineralization in grazed ecosystems. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15:32-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2012.12.001 Sitters J, Venterink HO. 2015. The need for a novel integrative theory on feedbacks between herbivores, plants and soil nutrient cycling. Plant and Soil 396:421-426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2679-y Sitters J, Wubs EJ, Bakker ES, Crowther TW, Adler PB, Bagchi S, Bakker JD, Biederman L, Borer ET, Cleland EE. 2020. Nutrient availability controls the impact of mammalian herbivores on soil carbon and nitrogen pools in grasslands. Global Change Biology 26:2060-2071. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15023 Speed JD, Austrheim G. 2017. The importance of herbivore density and management as determinants of the distribution of rare plant species. Biological Conservation 205:77-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.030 | Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands | Catherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault | <p>Background and Aims: Understanding how direct and indirect changes in climatic conditions, management, and species composition affect root production and root traits is of prime importance for the delivery of carbon sequestration services of gr... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning | Jennifer Krumins | 2020-08-30 19:27:30 | View | |

14 Jul 2023

Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlandsMallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780Searching for conservation opportunities at the marginsRecommended by Ana S. L. Rodrigues based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción

In a progressively human-dominated planet (Venter et al., 2016), the fate of many species will depend on the extent to which they can persist in anthropogenic landscapes. In Western Europe, where only small areas of primary habitat remain (e.g. Sabatini et al., 2018), semi-natural areas are crucial habitats to many native species, yet they are threatened by the expansion of human activities, including agricultural expansion and intensification (Rigal et al., 2023). A new study by Mallet and colleagues (Mallet et al., 2023) investigates the extent to which bird species in the Camargue region are able to use the margins of agricultural fields as substitutes for their preferred semi-natural habitats. Located in the delta of the Rhône River in Southern France, the Camargue is internationally recognized for its biodiversity value, classified as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO and as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention (IUCN & UN-WCMC, 2023). Mallet and colleagues tested three specific hypotheses: that grass strips (grassy field boundaries, including grassy tracks or dirt roads used for moving agricultural machinery) can function as substitute habitats for grassland species; that reed strips along drainage ditches (common in the rice paddy landscapes of the Camargue) can function as substitute habitats to wetland species; and that hedgerows can function as substitute habitats to species that favour woodland edges. They did so by measuring how the local abundances of 14 bird species (nine typical of forest edges, 3 of grasslands, and two of reedbeds) respond to increasing coverage of either the three types of field margins or of the three types of semi-natural habitat. This is an elegant study design, yet – as is often the case with real field data – results are not as simple as expected. Indeed, for most species (11 out of 14) local abundances did not increase significantly with the area of their supposed primary habitat, undermining the assumption that they are strongly associated with (or dependent on) those habitats. Among the three species that did respond positively to the area of their primary habitat, one (a forest edge species) responded positively but not significantly to the area of field margins (hedgerows), providing weak evidence to the habitat compensation hypothesis. For the other two (grassland and a wetland species), abundance responded even more strongly to the area of field margins (grass and reed strips, respectively) than to the primary habitat, suggesting that the field margins are not so much a substitute but valuable habitats in their own right. It would have been good conservation news if field margins were found to be suitable habitat substitutes to semi-natural habitats, or at least reasonable approximations, to most species. Given that these margins have functional roles in agricultural landscapes (marking boundaries, access areas, water drainage), they could constitute good win-win solutions for reconciling biodiversity conservation with agricultural production. Alas, the results are more complicated than that, with wide variation in species responses that could not have been predicted from presumed habitat affinities. These results illustrate the challenges of conservation practice in complex landscapes formed by mosaics of variable land use types. With species not necessarily falling neatly into habitat guilds, it becomes even more challenging to plan strategically how to manage landscapes to optimize their conservation. The results presented here suggest that species’ abundances may be responding to landscape variables not taken into account in the analyses, such as connectivity between habitat patches, or maybe positive and negative edge effects between land use types. That such uncertainties remain even in a well-studied region as the Camargue, and for such a well-studied taxon such as birds, only demonstrates the continued importance of rigorous field studies testing explicit hypotheses such as this one by Mallet and colleagues. References IUCN, & UN-WCMC (2023). Protected Planet. Protected Planet. https://www.protectedplanet.net/en Mallet, P., Béchet, A., Sirami, C., Mesléard, F., Blanchon, T., Calatayud, F., Dagonet, T., Gaget, E., Leray, C., & Galewski, T. (2023). Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490780, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780 Rigal, S., Dakos, V., Alonso, H., Auniņš, A., Benkő, Z., Brotons, L., Chodkiewicz, T., Chylarecki, P., de Carli, E., del Moral, J. C. et al. (2023). Farmland practices are driving bird population decline across Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120, e2216573120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216573120 Sabatini, F. M., Burrascano, S., Keeton, W. S., Levers, C., Lindner, M., Pötzschner, F., Verkerk, P. J., Bauhus, J., Buchwald, E., Chaskovsky, O., Debaive, N. et al. (2018). Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Diversity and Distributions, 24, 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12778 Venter, O., Sanderson, E. W., Magrach, A., Allan, J. R., Beher, J., Jones, K. R., Possingham, H. P., Laurance, W. F., Wood, P., Fekete, B. M., Levy, M. A., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nature Communications, 7, 12558. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12558 | Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands | Mallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding birds in agricultural landscapes have declined considerably since the 1950s and the beginning of agricultural intensification in Europe. Given the increasing pressure on agricultural land, it is necessary t... | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Landscape ecology | Ana S. L. Rodrigues | 2022-05-09 10:48:49 | View | ||

20 Feb 2023

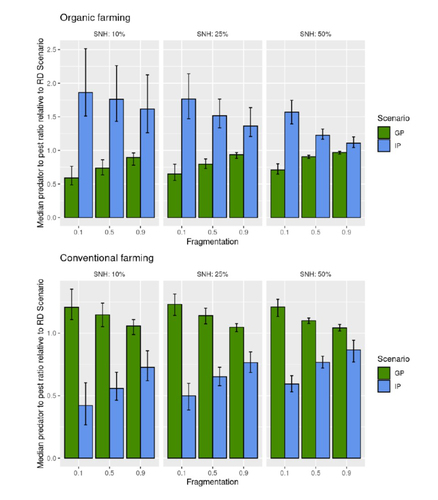

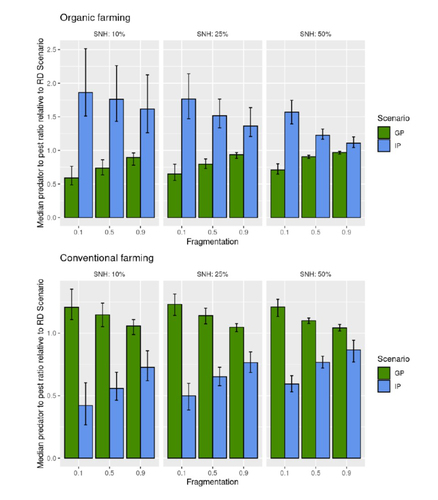

Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approachThomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006Towards model-guided organic farming expansion for crop pest managementRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart

Reduce the impact the intensification of human activities has on the environmental is the challenge the humanity faces today, a major challenge that could be compared to climbing Everest without an oxygen supply. Indeed, over-population, pollution, burning fossil fuels, and deforestation are all evils which have had hugely detrimental effects on the environment such as climate change, soil erosion, poor air quality, and scarcity of drinking water to name but a few. In response to the ever-growing consumer demand, agriculture has intensified massively along with a drastic increase in the use of chemicals to ensure an adequate food supply while controlling crop pests. In this context, to address the disastrous effects of the intensive usage of pesticides on both human health and biodiversity, organic farming (OF) revealed as a miracle remedy with multiple benefits. Delattre et al. (2023) present a powerful modelling approach to decipher the crossed effects of the landscape structure and the OF expansion scenario on the pest abundance, both in organic and conventional (CF) crop fields. To this end, the authors ingeniously combined a grid-based landscape model with a spatially explicit predator-pest model. Based on an extensive in silico simulation process, they explore a diversity of landscape structures differing in their amount of semi-natural habitats (SHN) and in their fragmentation, to finally propose a ranking of various expansion scenarios according to the pest control methods in organic farming as well as to the pest and predators’ dissemination capacities. In total, 9 landscape structures (3 proportions of SHN x 3 fragmentation levels) were crossed with 3 expansion scenarios (RD = a random distribution of OF and CF in the grid; IP = isolated CF are converted; GP = CF within aggregates are converted), 4 pest management practices, 3 initial densities and 36 biological parameter combinations driving the predator’ and pest’s population dynamics. This exhaustive exploration of possible combinations of landscape and farming practices highlighted the main drivers of the various OF expansion scenarios, such as increased spillover of predators in isolated OF/CF fields, increased pest management efficiency in large patches of CF and the importance of the distance between OF and CF. In the end, this study brings to light the crucial role that landscape planning plays when OF practices have limited efficiency on pests. It also provides convincing arguments to the fact that converting to organic isolated CF as a priority seems to be the most promising scenario to limit pest densities in CF crops while improving predator to pest ratios (considered as a proxy of conservation biological control) in OF ones without increasing pest densities. Once further completed with model calibration validation based on observed life history traits data for both predators and pests, this work should be very helpful in sustaining policy makers to convince farmers of engaging in organic farming. REFERENCES Delattre T, Memah M-M, Franck P, Valsesia P, Lavigne C (2023) Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach. bioRxiv, 2022.05.31.494006, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006 | Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach | Thomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organic Farming (OF) has been expanding recently around the world in response to growing consumer demand and as a response to environmental concerns. Its share of agricultural landscapes is expected to increase in t... |  | Agroecology, Biological control, Landscape ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-06-03 11:41:14 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

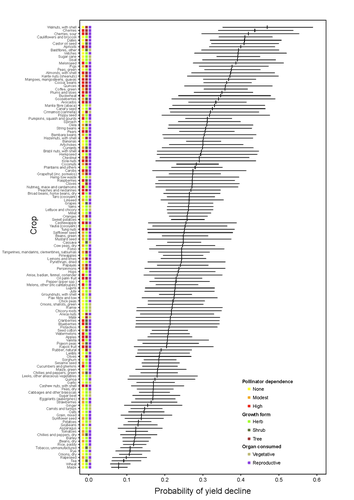

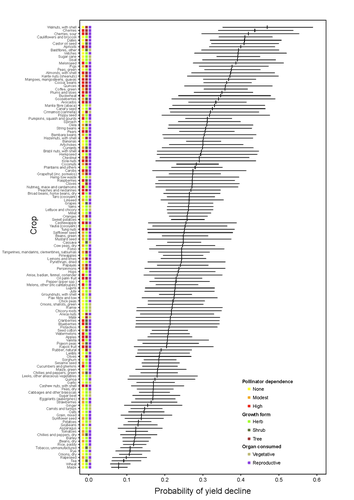

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

01 Feb 2020

Touchy matter: the delicate balance between Morgan’s canon and open-minded description of advanced cognitive skills in the animalRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Valérie Dufour and Alex Taylor based on reviews by Valérie Dufour and Alex Taylor

In a recent paper published in PNAS, Fayet et al. [1] reported scarce field observations of two Atlantic puffins (four years apart) apparently scratching their bodies using sticks, which was interpreted by the authors as evidence of tool use in this species. In a short response, Benjamin Farrar [2] raises serious concerns about this interpretation and proposes simpler, more parsimonious, mechanisms explaining the observed behaviour: a textbook case of Morgan's canon. References [1] Fayet, A. L., Hansen, E. S., and Biro, D. (2020). Evidence of tool use in a seabird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(3), 1277–1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918060117 | Evidence of tool use in a seabird? | Benjamin G. Farrar | Fayet, Hansen and Biro (1) provide two observations of Atlantic puffins, *Fratercula arctica*, performing self-directed actions while holding a stick in their beaks. The authors interpret this as evidence of tool use as they suggest that the stick... |  | Behaviour & Ethology | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2020-01-22 11:55:27 | View | |

31 May 2022

Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill populationNikolaos Smit, Alice Baniel, Berta Roura-Torres, Paul Amblard-Rambert, Marie J. E. Charpentier, Elise Huchard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.07.479393Rare behaviours can have strong effects: evidence for sexual coercion in mandrillsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Micaela Szykman Gunther and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Micaela Szykman Gunther and 1 anonymous reviewer

Sexual coercion can be defined as the use by a male of force, or threat of force, which increases the chances that a female will mate with him at a time when she is likely to be fertile, and/or decrease the chances that she will mate with other males, at some cost to the female (Smuts & Smuts 1993). It has been evidenced in a wide range of species and may play an important role in the evolution of sexual conflict and social systems. However, identifying sexual coercion in natural systems can be particularly challenging. Notably, while male behaviour may have immediate consequences on mating success (“harassment”), the mating benefits may be delayed in time (“intimidation”), and in such cases, evidencing coercion requires detailed temporal data at the individual level. Moreover, in some species male aggressive behaviours may be subtle or rare and hence hardly observed, yet still have important effects on female mating probability and fitness. Therefore, investigating the occurrence and consequences of sexual coercion in such species is particularly relevant but studying it in a statistically robust way is likely to require a considerable amount of time spent observing individuals. In this paper, Smit et al. (2022) test three clear predictions of the sexual coercion hypothesis in a natural population of Mandrills, where severe male aggression towards females is rare: (1) male aggression is more likely on sexually receptive females than on females in other reproductive states, (2) receptive females are more likely to be injured and (3) male aggression directed towards females is positively related to subsequent probability of copulation between those dyads. They also tested an alternative hypothesis, the “aggressive male phenotype” under which the correlation between male aggression towards females and subsequent mating could be statistically explained by male overall aggressivity. In agreement with the three predictions of the sexual coercion hypothesis, (1) male aggression was on average 5 times more likely, and (2) injuries twice as likely, to be observed on sexually receptive females than on females in other reproductive states and (3) copulation between males and sexually receptive females was twice more likely to be observed when aggression by this male was observed on the female before sexual receptivity. There was no support for the aggressive male hypothesis. The reviewers and I were highly positive about this study, notably regarding the way it is written and how the predictions are carefully and clearly stated, tested, interpreted, and discussed. This study is a good illustration of a case where some behaviours may not be common or obvious yet have strong effects and likely important consequences and thus be clearly worth studying. More generally, it shows once more the importance of detailed long-term studies at the individual level for our understanding of the ecology and evolution of wild populations. It is also a good illustration of the challenges faced, when comparing the likelihood of contrasting hypotheses means we need to alter sample sizes and/or the likelihood to observe at all some behaviours. For example, observing copulation within minutes after aggression (and therefore, showing statistical support for “harassment”) is inevitably less likely than observing copulations on the longer-term (and therefore showing statistical support for “intimidation”, when of course effort is put into recording such behavioural data on the long-term). Such challenges might partly explain some apparently intriguing results. For example, why are swollen females more aggressed by males if only aggression before the swollen period seems associated with more chances of mating? Here, the authors systematically provide effect sizes (and confidence intervals) and often describe the effects in an intuitive biological way (e.g., “Swollen females were, on average, about five times more likely to become injured”). This clearly helps the reader to not merely compare statistical significances but also the biological strengths of the estimated effects and the uncertainty around them. They also clearly acknowledge limits due to sample size when testing the harassment hypothesis, yet they provide precious information on the probability of observing mating (a rare behaviour) directly after aggression (already a rare behaviour!), that is, 3 times out of 38 aggressions observed between a male and a swollen female. Once again, this highlights how important it is to be able to pursue the enormous effort put so far into closely and continuously monitoring this wild population. Finally, this study raises exciting new questions, notably regarding to what extent females exhibit “counter-strategies” in response to sexual coercion, notably whether there is still scope for female mate choice under such conditions, and what are the fitness consequences of these dynamic conflicting sexual interactions. No doubt these questions will sooner than later be addressed by the authors, and I am looking forward to reading their upcoming work. References Smit N, Baniel A, Roura-Torres B, Amblard-Rambert P, Charpentier MJE, Huchard E (2022) Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill population. bioRxiv, 2022.02.07.479393, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.07.479393 Smuts BB, Smuts R w. (1993) Male Aggression and Sexual Coercion of Females in Nonhuman Primates and Other Mammals: Evidence and Theoretical Implications. In: Advances in the Study of Behavior (eds Slater PJB, Rosenblatt JS, Snowdon CT, Milinski M), pp. 1–63. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3454(08)60404-0 | Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill population | Nikolaos Smit, Alice Baniel, Berta Roura-Torres, Paul Amblard-Rambert, Marie J. E. Charpentier, Elise Huchard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Increasing evidence indicates that sexual coercion is widespread. While some coercive strategies are conspicuous, such as forced copulation or sexual harassment, less is known about the ecology and evolution of inti... |  | Behaviour & Ethology | Matthieu Paquet | 2022-02-11 09:32:49 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle