BARTOMEUS Ignasi

- Ecology and Evolution, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC), Seville, Spain

- Agroecology, Biodiversity, Biological invasions, Climate change, Coexistence, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Facilitation & Mutualism, Interaction networks, Landscape ecology, Pollination

- recommender

Recommendations: 4

Reviews: 3

Recommendations: 4

Code-sharing policies are associated with increased reproducibility potential of ecological findings

Ensuring reproducible science requires policies

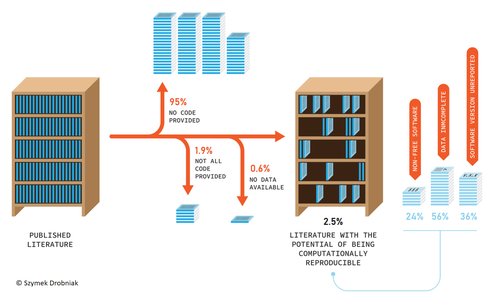

Recommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Francisco Rodriguez-Sanchez and Veronica CruzResearchers do not live in a vacuum, and the social context we live in affects how we do science. On one hand, increased competition for scarce funding creates the wrong incentives to do fast analysis, leading sometimes to poorly checked results that accumulate errors (Fraser et al. 2018). On the other hand, the actual challenges the world faces require more than ever robust scientific evidence that can be used to tackle the current rapid human-induced environmental change. Moreover, scientists' credibility is at stake at this moment where the global flow of information can be politically manipulated, and accessing reliable sources of information is paramount for society. At the crossroads of these challenges is scientific reproducibility. Making our results transparent and reproducible ensures that no perverse incentives can compromise our findings, that results can be reliably applied to solve relevant problems, and that we regain societal credibility in the scientific process. Unfortunately, in ecology and evolution, we are still far from publishing open, transparent, and reproducible papers (Maitner et al. 2024). Understanding which factors promote increased use of good practices regarding reproducibility is hence very welcome.

Sanchez-Tojar and colleagues (2025) conducted a (reproducible) analysis of code and data-sharing practices (a cornerstone of scientific reproducibility) in journals with and without explicit policies regarding data and code deposition. The gist is that having policies in place increases data and code sharing. Doing science about how we do science (meta-science) is important to understand which actions drive our behavior as scientists. This paper highlights that in the absence of strong societal or personal incentives to share code and data, clear policies can catalyze this process. However, in my opinion, policies are a needed first step to consolidate a more permanent change in researchers' behavior regarding reproducible science, but policies alone will not be enough to fix the problem if we do not change also the cultural values around how we publish science. Appealing to inner values, and recognizing science needs to be reproducible to ensure potential errors are easily spotted and corrected requires a deep cultural change.

References

Fraser, Hannah, Tim Parker, Shinichi Nakagawa, Ashley Barnett, and Fiona Fidler. "Questionable research practices in ecology and evolution." PloS one 13, no. 7 (2018): e0200303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200303

Maitner, Brian, Paul Efren Santos Andrade, Luna Lei, Jamie Kass, Hannah L. Owens, George CG Barbosa, Brad Boyle et al. "Code sharing in ecology and evolution increases citation rates but remains uncommon." Ecology and Evolution 14, no. 8 (2024): e70030. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.70030

Alfredo Sánchez-Tójar, Aya Bezine, Marija Purgar, Antica Culina (2025) Code-sharing policies are associated with increased reproducibility potential of ecological findings. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X21S7H

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence

The complexities of understanding why yield is declining

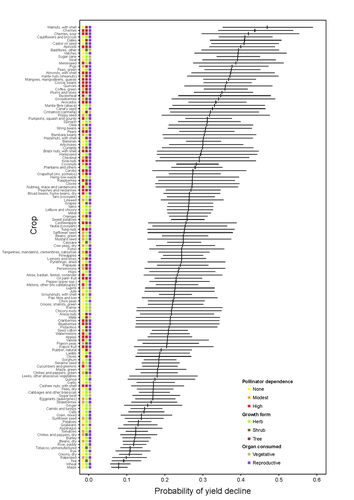

Recommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewerDespite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges.

References

Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617

Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340

Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108

Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees

The importance of understanding bee nutrition

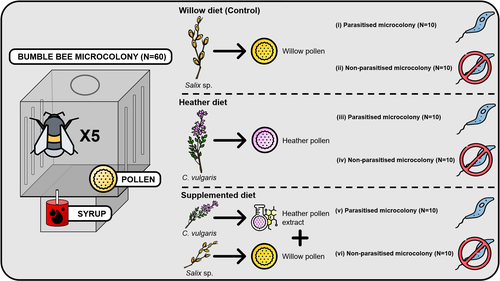

Recommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewerContrasting with the great alarm on bee declines, it is astonishing how little basic biology we know about bees, including on abundant and widespread species that are becoming model species. Plant-pollinator relationships are one of the cornerstones of bee ecology, and researchers are increasingly documenting bees' diets. However, we rarely know which effects feeding on different flowers has on bees' health. This paper (Tourbez et al. 2023) uses an elegant experimental setting to test the effect of heather pollen on bumblebees' (Bombus terrestris) reproductive success. This is a timely question as heather is frequently used by bumblebees, and its nectar has been reported to reduce parasite infections. In fact, it has been suggested that bumblebees can medicate themselves when infected (Richardson et al. 2014), and the pollen of some Asteraceae has been shown to help them fight parasites (Gekière et al. 2022). The starting hypothesis is that heather pollen contains flavonoids that might have a similar effect. Unfortunately, Tourbez and collaborators do not support this hypothesis, showing a negative effect of heather pollen, in particular its flavonoids, in bumblebees offspring, and an increase in parasite loads when fed on flavonoids. This is important because it challenges the idea that many pollen and nectar chemical compounds might have a medicinal use, and force us to critically analyze the effect of chemical compounds in each particular case. The results open several questions, such as why bumblebees collect heather pollen, or in which concentrations or pollen mixes it is deleterious. A limitation of the study is that it uses micro-colonies, and extrapolating this to real-world conditions is always complex. Understanding bee declines require a holistic approach starting with bee physiology and scaling up to multispecies population dynamics.

References

Gekière, A., Semay, I., Gérard, M., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., & Vanderplanck, M. 2022. Poison or Potion: Effects of Sunflower Phenolamides on Bumble Bees and Their Gut Parasite. Biology, 11(4), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040545

Richardson, L.L., Adler, L.S., Leonard, A.S., Andicoechea, J., Regan, K.H., Anthony, W.E., Manson, J.S., & Irwin, R.E. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 282 (1803), 20142471. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2471

Tourbez, C., Semay, I., Michel, A., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., Gekière A. & Vanderplanck, M. 2023. Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees. Zenodo, ver 3, reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8192036

Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities?

On the importance of experimental design: pitfall traps and arthropod communities

Recommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cécile ALBERT and Matthias FoellmerDespite the increasing refinement of statistical methods, a robust experimental design is still one of the most important cornerstones to answer ecological and evolutionary questions. However, there is a strong trade-off between a perfect design and its feasibility. A common mantra is that more data is always better, but how much is enough is complex to answer, specially when we want to capture the spatial and temporal variability of a given process. Gardarin and Valantin-Morison [1] make an effort to answer these questions for a practical case: How many pitfalls traps, of which type, and over which extent, do we need to detect shifts in arthropod community composition in agricultural landscapes. There is extense literature on how to approach these challenges using preliminary data in combination with simulation methods [e.g. 2], but practical cases are always welcomed to illustrate the complexity of the decisions to be made. A key challenge in this situation is the nature of simplified and patchy agricultural arthropod communities. In this context, small effect sizes are expected, but those small effects are relevant from an ecological point of view because small increases at low biodiversity may produce large gains in ecosystem functioning [3].

The paper shows that some variables are not important, such as the type of fluid used to fill the pitfall traps. This is good news for potential comparisons among studies using slightly different protocols. However, the bad news are that the sampling effort needed for detecting community changes is larger than the average effort currently implemented. A potential solution is to focus on Community Weighed Mean metrics (CWM; i.e. a functional descriptor of the community body size distribution) rather than on classic metrics such as species richness, as detecting changes on CWM requires a lower sampling effort and it has a clear ecological interpretation linked to ecosystem functioning.

Beyond the scope of the data presented, which is limited to a single region over two years, and hence it is hard to extrapolate to other regions and years, the big message of the paper is the need to incorporate statistical power simulations as a central piece of the ecologist's toolbox. This is challenging, especially when you face questions such as: Should I replicate over space, or over time? The recommended paper is accompanied by the statistical code used, which should facilitate this task to other researchers. Furthermore, we should be aware that some important questions in ecology are highly variable in space and time, and hence, larger sampling effort across space and time is needed to detect patterns. Larger and longer monitoring schemes require a large effort (and funding), but if we want to make relevant ecology, nobody said it would be easy.

References

[1] Gardarin, A. and Valantin-Morison, M. (2019). Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities? Zenodo, 3468920, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3468920

[2] Johnson, P. C., Barry, S. J., Ferguson, H. M., and Müller, P. (2015). Power analysis for generalized linear mixed models in ecology and evolution. Methods in ecology and evolution, 6(2), 133-142. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12306

[3] Cardinale, B. J. et al. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486(7401), 59-67. doi: 10.1038/nature11148

Reviews: 3

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices

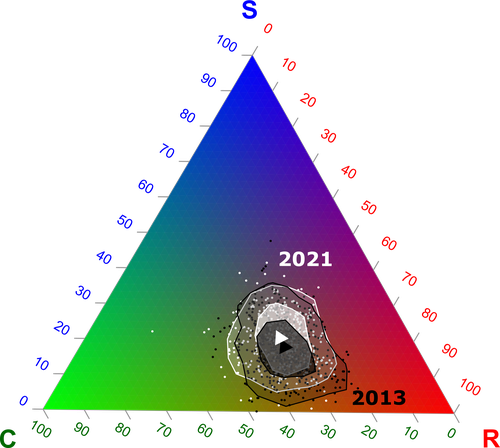

Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persist

Recommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clélia Sirami and Diego GurvichAgricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ.

In this vein, the study of Poinas et al. (2024) can be considered a key contribution. It exemplifies how agricultural intensification practiced in the context of climate change can constrain the potential of agricultural field margin flora to cope with climatic variations. The authors found that the incidence of plant strategies better adapted to climate change (conservative/stress-tolerant and Mediterranean species) increased with higher temperatures and lower soil moisture, and with lower intensity of margin management. In contrast, the incidence of ruderal species decreased with climate change. Thus, increasing or even maintaining current levels of agricultural intensification may affect the potential of French agriculture to move to sustainable process-based agricultures because of the reduction of plant diversity, particularly of vegetation better adapted to climate change.

By using an impressive dataset spanning 9 years and 555 agricultural margins in continental France, Poinas et al. (2024) investigated temporal changes in climatic variables (temperature and soil moisture), agricultural practices (herbicide and fertilizers quantity, the frequency of margin mowing or grinding), plant taxonomical and functional diversity, plant strategies (Grime 1977, 1988) and relationships between these temporal changes. Temporal changes in plant strategies were associated with those observed in climatic variables and agricultural practices. Even such associations seem to be mediated by spatial changes, as described in the supplementary material and in their most recent article (Poinas et al. 2023), changes in climatic variables registered in a decade shaped plant strategies and therefore the diversity and functional potential of agricultural field margins. These results are clearly synthesized in Figures 6 and 7 of the present contribution.

As shown by Poinas et al. (2024), in the context of climate change, decreasing agricultural intensification will produce more diverse agricultural field margins by promoting the persistence of plant species better adapted to higher temperatures and lower soil moisture. Thus, adopting other agricultural practices (e.g., agroforestry, agroecology) will produce territories with a higher potential to move to sustainable processes-based agricultures that may better cope with climate change by harboring higher biocultural diversity (Altieri et al. 2015).

References

Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013

Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2

Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005

Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244

Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14

Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain.

Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003

Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956

Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715

Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring

How to evaluate and interpret the contribution of species turnover and interaction rewiring when comparing ecological networks?

Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewerA network includes a set of vertices or nodes (e.g., species in an interaction network), and a set of edges or links (e.g., interactions between species). Whether and how networks vary in space and/or time are questions often addressed in ecological research.

Two ecological networks can differ in several extents: in that species are different in the two networks and establish new interactions (species turnover), or in that species that are present in both networks establish different interactions in the two networks (rewiring). The ecological meaning of changes in network structure is quite different according to whether species turnover or interaction rewiring plays a greater role. Therefore, much attention has been devoted in recent years on quantifying and interpreting the relative changes in network structure due to species turnover and/or rewiring.

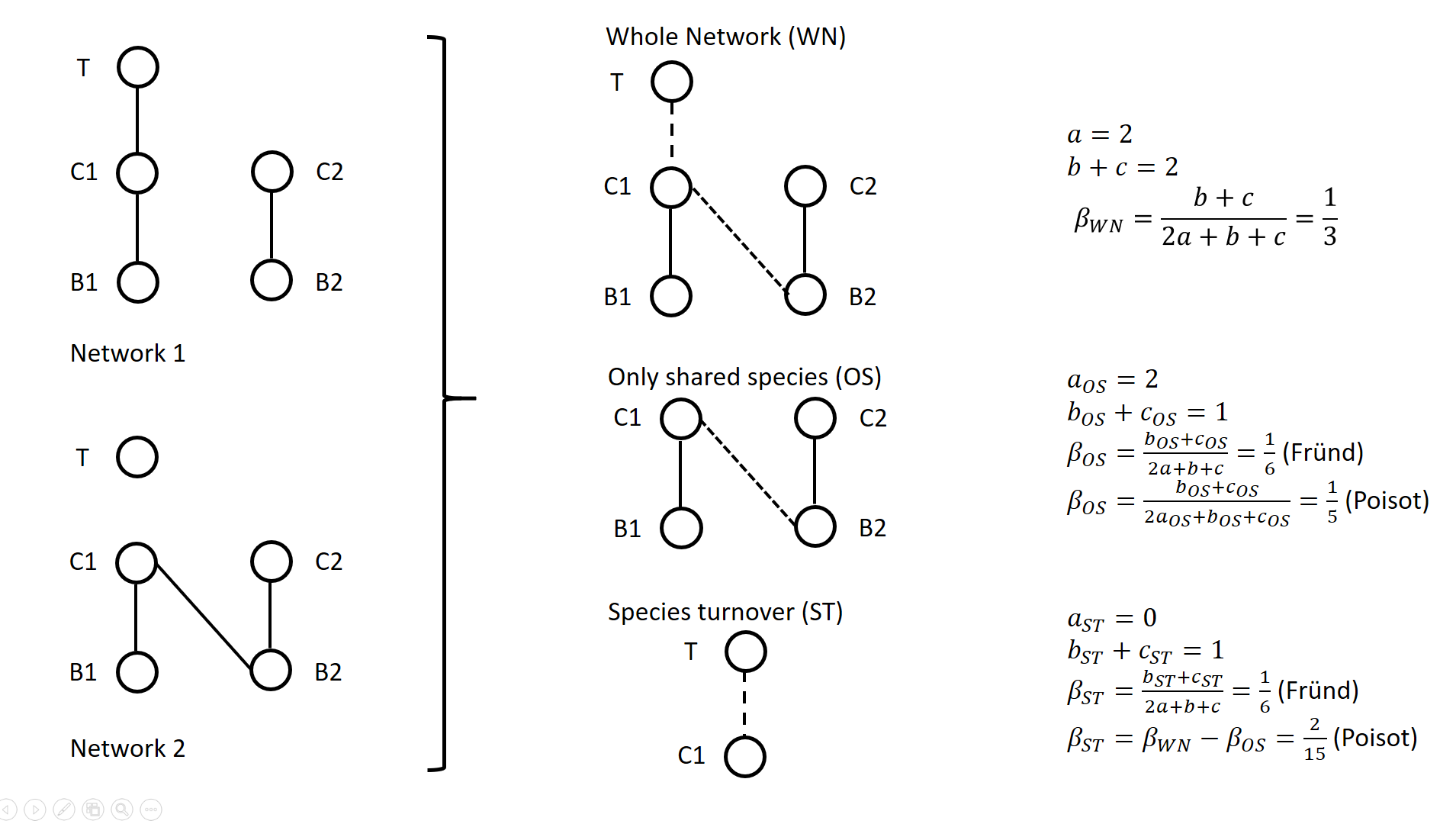

Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to partition the global variation in structure between networks, \( \beta_{WN} \) (WN = Whole Network) into two terms: \( \beta_{OS} \) (OS = Only Shared species) and \( \beta_{ST} \) (ST = Species Turnover), such as \( \beta_{WN} = \beta_{OS} + \beta_{ST} \).

The calculation lays on enumerating the interactions between species that are common or not to two networks, as illustrated on Figure 1 for a simple case. Specifically, Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to use a Sorensen type measure of network dissimilarity, i.e., \( \beta_{WN} = \frac{a+b+c}{(2a+b+c)/2} -1=\frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} \) , where \( a \) is the number of interactions shared between the networks, while \( b \) and \( c \) are interaction numbers unique to one and the other network, respectively. \( \beta_{OS} \) is calculated based on the same formula, but only for the subnetworks including the species common to the two networks, in the form \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a_{OS}+b_{OS}+c_{OS}} \) (e.g., Fig. 1). \( \beta_{ST} \) is deduced by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and represents in essence a "dissimilarity in interaction structure introduced by dissimilarity in species composition" (Poisot et al. 2012).

Figure 1. Ecological networks exemplified in Fründ (2021) and discussed in Poisot (2022). a is the number of shared links (continuous lines in right figures), while b+c is the number of edges unique to one or the other network (dashed lines in right figures).

Alternatively, Fründ (2021) proposed to define \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a+b+c} \) and \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} \), where \( b_{ST}=b-b_{OS} \) and \( c_{ST}=c-c_{OS} \) , so that the components \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) have the same denominator. In this way, Fründ (2021) partitioned the count of unique \( b+c=b_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST} \) interactions, so that \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) sums to \( \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} = \frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} = \beta_{WN} \). Fründ (2021) advocated that this partition allows a more sensible comparison of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \), in terms of the number of links that contribute to each component.

For instance, let us consider the networks 1 and 2 in Figure 1 (left panel) such as \( a_{OS}=2 \) (continuous lines in right panel), \( b_{ST} + c_{ST} = 1 \) and \( b_{OS} + c_{OS} = 1 \) (dashed lines in right panel), and thereby \( a = 2 \), \( b+c=2 \), \( \beta_{WN} = 1/3 \). Fründ (2021) measured \( \beta_{OS}=\beta_{ST}=1/6 \) and argued that it is appropriate insofar as it reflects that the number of unique links in the OS and ST components contributing to network dissimilarity (dashed lines) are actually equal. Conversely, the formula of Poisot et al. (2012) yields \( \beta_{OS}=1/5 \), hence \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{5}=\frac{2}{15}<\beta_{OS} \). Fründ (2021) thus argued that the method of Poisot tends to underestimate the contribution of species turnover.

To clarify and avoid misinterpretation of the calculation of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) in Poisot et al. (2012), Poisot (2022) provides a new, in-depth mathematical analysis of the decomposition of \( \beta_{WN} \). Poisot et al. (2012) quantify in \( \beta_{OS} \) the actual contribution of rewiring in network structure for the subweb of common species. Poisot (2022) thus argues that \( \beta_{OS} \) relates only to the probability of rewiring in the subweb, while the definition of \( \beta_{OS} \) by Fründ (2021) is relative to the count of interactions in the global network (considered in denominator), and is thereby dependent on both rewiring probability and species turnover. Poisot (2022) further clarifies the interpretation of \( \beta_{ST} \). \( \beta_{ST} \) is obtained by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and thus represents the influence of species turnover in terms of the relative architectures of the global networks and of the subwebs of shared species. Coming back to the example of Fig.1., the Poisot et al. (2012) formula posits that \( \frac{\beta_{ST}}{\beta_{WN}}=\frac{2/15}{1/3}=2/5 \), meaning that species turnover contributes two-fifths of change in network structure, while rewiring in the subweb of common species contributed three fifths. Conversely, the approach of Fründ (2021) does not compare the architectures of global networks and of the subwebs of shared species, but considers the relative contribution of unique links to network dissimilarity in terms of species turnover and rewiring.

Poisot (2022) concludes that the partition proposed in Fründ (2021) does not allow unambiguous ecological interpretation of rewiring. He provides guidelines for proper interpretation of the decomposition proposed in Poisot et al. (2012).

References

Fründ J (2021) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: how to partition rewiring and species turnover components. Ecosphere, 12, e03653. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3653

Poisot T, Canard E, Mouillot D, Mouquet N, Gravel D (2012) The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecology Letters, 15, 1353–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12002

Poisot T (2022) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring. EcoEvoRxiv Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands

The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradient

Recommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure.

In this preprint by Manincor et al. [3] the authors explore the effect of phenology overlap on a large network of species interactions in calcareous grasslands in France. They analyze if and how this effect varies along a latitudinal gradient using empirical data on six plant-hoverfly networks. When comparing ecological network along gradients a well-known problem is that the network metrics is dependent on network size [4]. Therefore, instead of focusing on complete network structure the authors here focus on the factors that determine the probability of interactions and interaction frequency (number of visits). The authors use Bayesian Structural Equation Models (SEM) to link the interaction probability and number of visits to phenology overlap and species abundance. SEM is a multivariate technique that can be used to test several hypotheses and evaluate multiple causal relationships using both observed and latent variables to explain some other observed variables. The authors provide a nice description of the approach for this type of study system. In addition, the study also tests whether phenology affects network compartmentalization, by analyzing species subgroups using a latent block model (LBM) which is a clustering method particularly well-suited for weighted networks.

The authors identify phenology overlap as an important determinant of plant-pollinator interactions, but also conclude this factor alone is not sufficient to explain the species interactions. Species abundances was important for number of visits. Plant phenology drives the duration of the phenology overlap between plant and hoverflies in the studied system. This in turn influences either the probability of interaction or the expected number of visits, as well as network compartmentalization. Longer phenologies correspond to lower modularity inferring less constrained interactions, and shorter phenologies correspond to higher modularity inferring more constrained interactions.

What make this study particularly interesting is the presentation of SEMs as an innovative approach to compare networks of different sizes along environmental gradients. The authors show that these methods can be a useful tool when the aim is to understand the structure of plant-pollinator networks and data is varying in complexities. During the review process the authors carefully addressed to the comments from the two reviewers and the manuscript improved during the process. Both reviewers have expertise highly relevant for the research performed and the development of the manuscript. In my opinion this is a highly interesting and valuable piece of work both when it comes to the scientific question and the methodology. I look forward to further follow this research.

References

[1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press.

[2] Parmesan, C. (2007). Influences of species, latitudes and methodologies on estimates of phenological response to global warming. Global Change Biology, 13(9), 1860-1872. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01404.x

[3] de Manincor, N., Hautekeete, N., Piquot, Y., Schatz, B., Vanappelghem, C. and Massol, F. (2019). Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands. Zenodo, 2543768, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.2543768

[4] Staniczenko, P. P., Kopp, J. C., and Allesina, S. (2013). The ghost of nestedness in ecological networks. Nature communications, 4, 1391. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2422