Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

05 Feb 2020

A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingMiriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://doi.org/10.1101/717355A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer

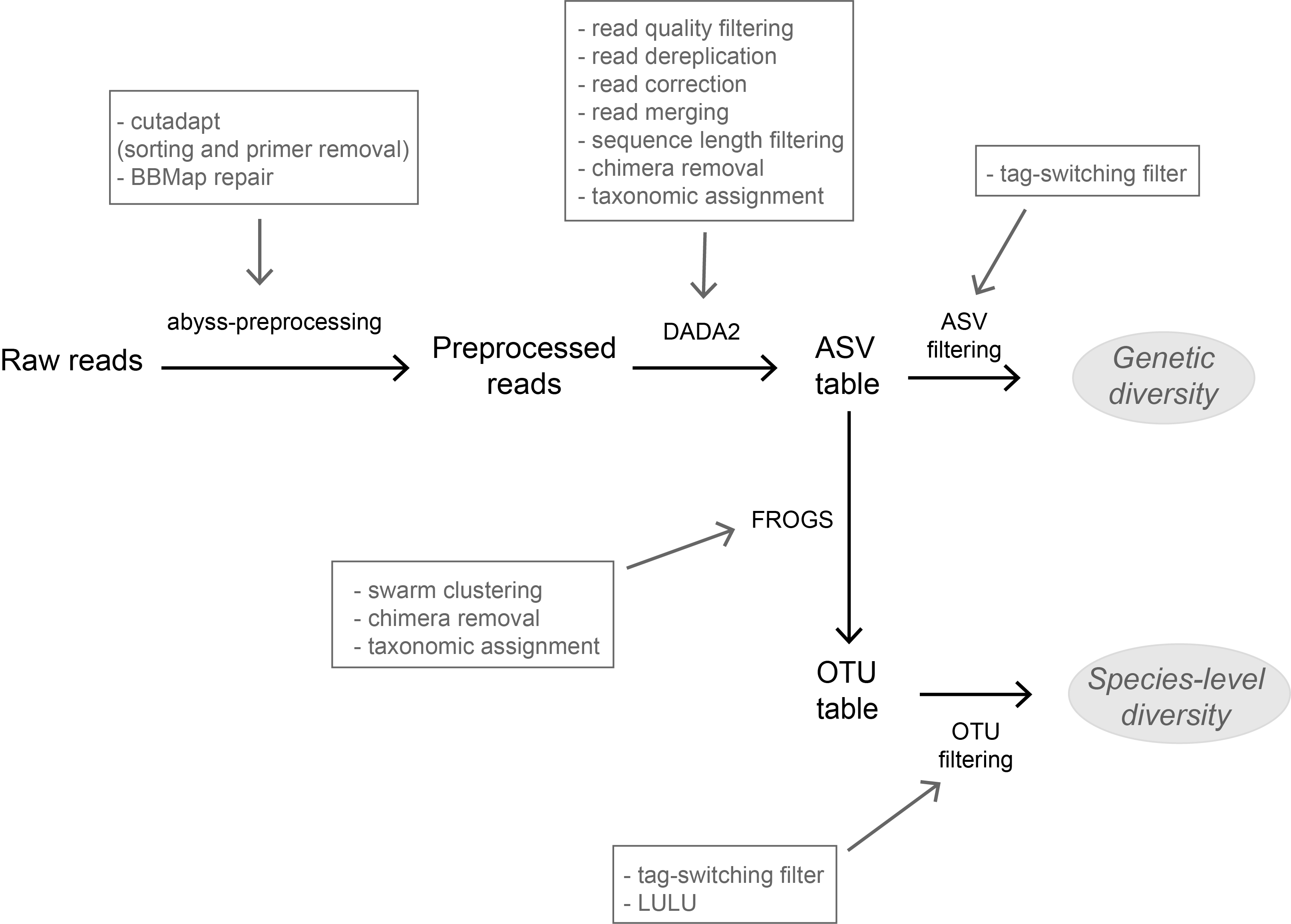

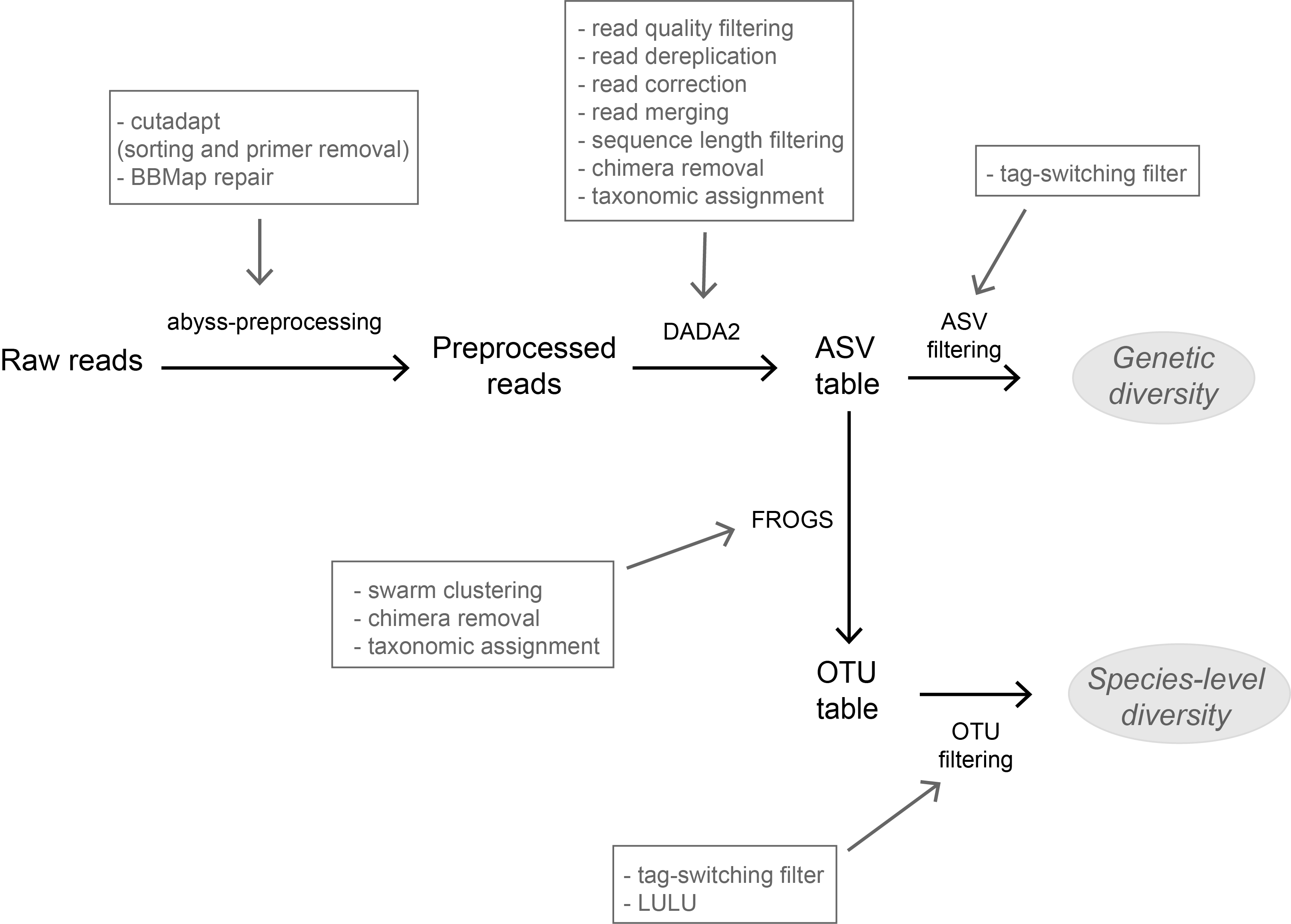

High-throughput sequencing-based techniques such as DNA metabarcoding are increasingly advocated as providing numerous benefits over morphology‐based identifications for biodiversity inventories and ecosystem biomonitoring [1]. These benefits are particularly apparent for highly-diversified and/or hardly accessible aquatic and marine environments, where simple water or sediment samples could already produce acceptably accurate biodiversity estimates based on the environmental DNA present in the samples [2,3]. However, sequence-based characterization of biodiversity comes with its own challenges. A major one resides in the capacity to disentangle true biological diversity (be it taxonomic or genetic) from artefactual diversity generated by sequence-errors accumulation during PCR and sequencing processes, or from the amplification of non-target genes (i.e. pseudo-genes). On one hand, the stringent elimination of sequence variants might lead to biodiversity underestimation through the removal of true species, or the clustering of closely-related ones. On the other hand, a more permissive sequence filtering bears the risks of biodiversity inflation. Recent studies have outlined an excellent methodological framework for addressing this issue by proposing bioinformatic tools that allow the amplicon-specific error-correction as alternative or as complement to the more arbitrary approach of clustering into Molecular Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) based on sequence dissimilarity [4,5]. But to date, the relevance of amplicon-specific error-correction tools has been demonstrated only for a limited set of taxonomic groups and gene markers. References [1] Porter, T. M., and Hajibabaei, M. (2018). Scaling up: A guide to high-throughput genomic approaches for biodiversity analysis. Molecular Ecology, 27(2), 313–338. doi: 10.1111/mec.14478 | A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcoding | Miriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Environmental metabarcoding is an increasingly popular tool for studying biodiversity in marine and terrestrial biomes. With sequencing costs decreasing, multiple-marker metabarcoding, spanning several branches of the tree of life, is becoming ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-08-02 20:52:45 | View | |

25 May 2021

Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assemblyCaio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho https://doi.org/10.1101/869966Environmental heterogeneity drives phytoplankton community assembly patterns in a tropical riverine systemRecommended by Cédric Hubas and Eric Goberville and Eric Goberville based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy

What predisposes two individuals to form and maintain a relationship is a fundamental question. Using facial recognition to see whether couples' faces change over time to become more and more similar, psychology researchers have concluded that couples tend to be formed from the start between people whose faces are more similar than average [1]. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. And what about in nature? Are these rules of assembly valid for communities of different species? In his seminal contribution, Robert MacArthur (1984) wrote ‘To do science is to search for repeated patterns’ [2]. Identifying the mechanisms that govern the arrangement of life is a hot research topic in the field of ecology for decades, and an absolutely essential prerequisite to answer the outstanding question of what shape ecological patterns in multi-species communities such as species-area relationships, relative species abundances, or spatial and temporal turnover of community composition; amid others [3]. To explain ecological patterns in nature, some rely on the concept that every species - through evolutionary processes and the acquisition of a unique set of traits that allow a species to be adapted to its abiotic and biotic environment - occupies a unique niche: Species coexistence comes as the result of niche differentiation [4,5]. Such a view has been challenged by the recognition of the key role of neutral processes [6], however, in which demographic stochasticity contributes to shape multi-species communities and to explain why congener species coexist much more frequently than expected by chance [7,8]. While the niche-based and neutral theories appear seemingly opposed at first sight [9], the dichotomy may be more philosophical than empirical [4,5]. Many examples have come to support that both concepts are not incompatible as they together influence the structure, diversity and functioning of communities [10], and are simply extreme cases of a continuum [11]. From this perspective, extrinsic factors, i.e., environmental heterogeneity, may influence the location of a given community along the niche-neutrality continuum. The walk of species in nature is therefore neither random nor ecologically predestined. In microbial assemblages, the co-existence of these two antagonistic mechanisms has been shown both theoretically and empirically. It has been shown that a combination of stabilising (niche) and equalising (neutral) mechanisms was responsible for the existence of groups of coexistent species (clumps) in a phytoplankton rich community [12]. Analysing interannual changes (2003-2009) in the weekly abundance of diatoms and dinoflagellates located in a temperate coastal ecosystem of the Western English Channel, Mutshinda et al. [13] found a mixture of biomass dynamics consistent with the neutrality-niche continuum hypothesis. While niche processes explained the dynamic of phytoplankton functional groups (i.e., diatoms vs. dinoflagellates) in terms of biomass, neutral processes mainly dominated - 50 to 75% of the time - the dynamics at the species level within functional groups [13]. From one endpoint to another, defining the location of a community along the continuum is all matter of scale [4,11]. In their study, testing predictions made by an emergent neutrality model, Graco-Roza et al. [14] provide empirical evidence that neutral and niche processes joined together to shape and drive planktonic communities in a riverine ecosystem. Body size - the 'master trait' - is used here as a discriminant ecological dimension along the niche axis. From their analysis, they not only show that the specific abundance is organised in clumps and gaps along the niche axis, but also reveal that different clumps exist along the river course. They identify two main clumps in body size - with species belonging to three different morphologically-based functional groups - and characterise that among-species differences in biovolume are driven by functional redundancy at the clump level; species functional distinctiveness being related to the relative biovolume of species. By grouping their variables according to seasons (cold-dry vs. warm-wet) or river elevation profile (upper, medium and lower course), they hereby highlight how environmental heterogeneity contributes to shape species assemblages and their dynamics and conclude that emergent neutrality models are a powerful approach to explain species coexistence; and therefore ecological patterns. References [1] Tea-makorn PP, Kosinski M (2020) Spouses’ faces are similar but do not become more similar with time. Scientific Reports, 10, 17001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73971-8. [2] MacArthur RH (1984) Geographical Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Species. Princeton University Press. [3] Vellend M (2020) The Theory of Ecological Communities (MPB-57). Princeton University Press. [4] Wennekes PL, Rosindell J, Etienne RS (2012) The Neutral—Niche Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. Acta Biotheoretica, 60, 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10441-012-9144-6. [5] Gravel D, Guichard F, Hochberg ME (2011) Species coexistence in a variable world. Ecology Letters, 14, 828–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01643.x. [6] Hubbell SP (2001) The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography (MPB-32). Princeton University Press. [7] Leibold MA, McPeek MA (2006) Coexistence of the Niche and Neutral Perspectives in Community Ecology. Ecology, 87, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1399:COTNAN]2.0.CO;2. [8] Pielou EC (1977) The Latitudinal Spans of Seaweed Species and Their Patterns of Overlap. Journal of Biogeography, 4, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038189. [9] Holt RD (2006) Emergent neutrality. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21, 531–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.003. [10] Scheffer M, Nes EH van (2006) Self-organized similarity, the evolutionary emergence of groups of similar species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 6230–6235. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508024103. [11] Gravel D, Canham CD, Beaudet M, Messier C (2006) Reconciling niche and neutrality: the continuum hypothesis. Ecology Letters, 9, 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00884.x. [12] Vergnon R, Dulvy NK, Freckleton RP (2009) Niches versus neutrality: uncovering the drivers of diversity in a species-rich community. Ecology Letters, 12, 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01364.x. [13] Mutshinda CM, Finkel ZV, Widdicombe CE, Irwin AJ (2016) Ecological equivalence of species within phytoplankton functional groups. Functional Ecology, 30, 1714–1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12641. [14] Graco-Roza C, Segura AM, Kruk C, Domingos P, Soininen J, Marinho MM (2021) Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly. bioRxiv, 869966, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/869966

| Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly | Caio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho | <p style="text-align: justify;">Emergent neutrality (EN) suggests that species must be sufficiently similar or sufficiently different in their niches to avoid interspecific competition. Such a scenario results in a transient pattern with clumps an... |  | Coexistence, Community ecology, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Hubas | 2020-01-23 16:11:32 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

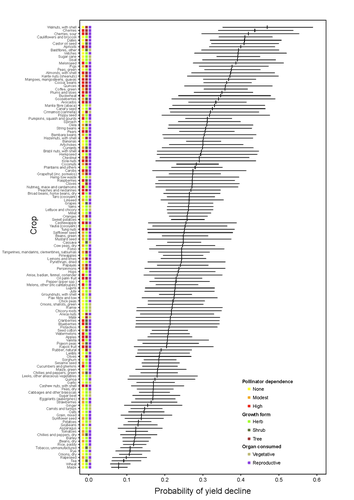

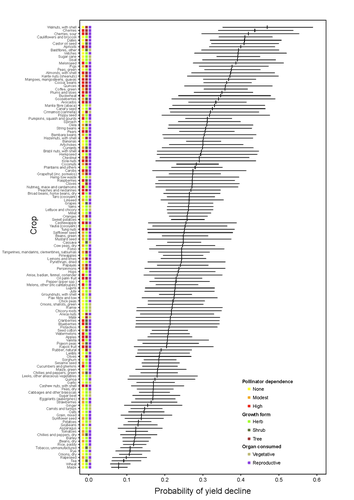

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View | ||

15 Jul 2023

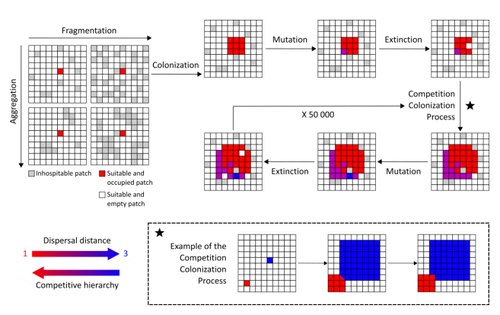

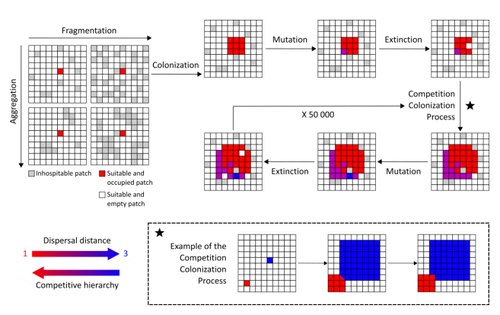

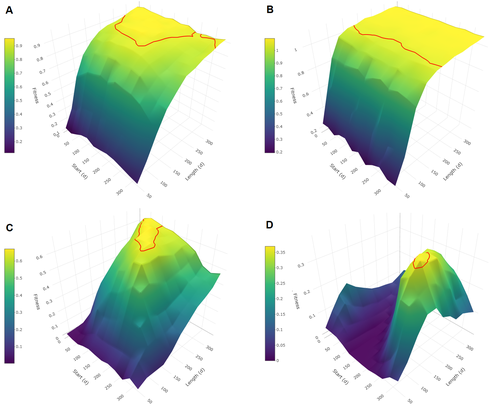

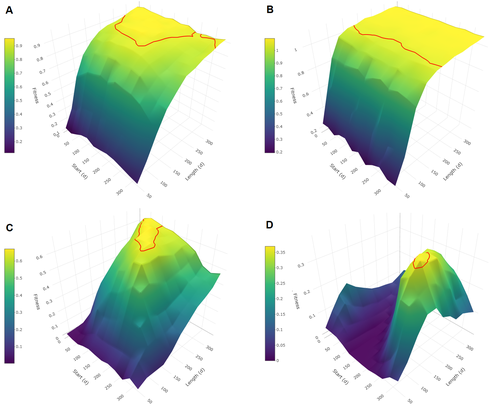

Evolution of dispersal and the maintenance of fragmented metapopulationsBasile Finand, Thibaud Monnin, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.08.495260The spatial dynamics of habitat fragmentation drives the evolution of dispersal and metapopulation persistenceRecommended by Frédéric Guichard based on reviews by Eva Kisdi, David Murray-Stoker, Shripad Tuljapurkar and 1 anonymous reviewerThe persistence of populations facing the destruction of their habitat is a multifaceted question that has mobilized theoreticians and empiricists alike for decades. As an ecological question, persistence has been studied as the spatial rescue of populations via dispersal into remaining suitable habitats. The spatial aggregation of habitat destruction has been a key component of these studies, and it has been applied to the problem of coexistence by integrating competition-colonization tradeoffs. There is a rich ecological literature on this topic, both from theoretical and field studies (Fahrig 2003). The relationship between life-history strategies of species and their resilience to spatially structured habitat fragmentation is also an important component of conservation strategies through the management of land use, networks of protected areas, and the creation of corridors. In the context of environmental change, the ability of species to adapt to changes in landscape configuration and availability can be treated as an eco-evolutionary process by considering the possibility of evolutionary rescue (Heino and Hanski 2001; Bell 2017). However, eco-evolutionary dynamics considering spatially structured changes in landscapes and life-history tradeoffs remains an outstanding question. Finand et al. (2023) formulate the problem of persistence in fragmented landscapes over evolutionary time scales by studying models for the evolution of dispersal in relation to habitat fragmentation and spatial aggregation. Their simulations were conducted on a spatial grid where individuals can colonize suitable patch as a function of their competitive rank that decreases as a function of their (ii) dispersal distance trait. Simulations were run under fixed habitat fragmentation (proportion of unsuitable habitat) and aggregation, and with an explicit rate of habitat destruction to study evolutionary rescue. Their results reveal a balance between the selection for high dispersal under increasing habitat fragmentation and selection for lower dispersal in response to habitat aggregation. This balance leads to the coexistence of polymorphic dispersal strategies in highly aggregated landscapes with low fragmentation where high dispersers inhabit aggregated habitats while low dispersers are found in isolated habitats. The authors then integrate the spatial rescue mechanism to the problem of evolutionary rescue in response to temporally increasing fragmentation. There they show how rapid evolution allows for evolutionary rescue through the evolution of high dispersal. They also show the limits to this evolutionary rescue to cases where both aggregation and fragmentation are not too high. Interestingly, habitat aggregation prevents evolutionary rescue by directly affecting the evolutionary potential of dispersal. The study is based on simple scenarios that ignore the complexity of relationships between dispersal, landscape properties, and species interactions. This simplicity is the strength of the study, revealing basic mechanisms that can now be tested against other life-history tradeoffs and species interactions. Finand et al. (2023) provide a novel foundation for the study of eco-evolutionary dynamics in metacommunities exposed to spatially structured habitat destruction. They point to important assumptions that must be made along the way, including the relationships between dispersal distance and fecundity (they assume a positive relationship), and the nature of life-history tradeoffs between dispersal rate and local competitive abilities.

Bell, G. 2017. Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48:605–627. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | Evolution of dispersal and the maintenance of fragmented metapopulations | Basile Finand, Thibaud Monnin, Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Because it affects dispersal risk and modifies competition levels, habitat fragmentation directly constrains dispersal evolution. When dispersal is traded-off against competitive ability, increased fragmentation is often expected to select high... |  | Colonization, Competition, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Frédéric Guichard | 2022-06-10 13:51:15 | View | |

19 Aug 2020

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metricsF. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux https://doi.org/10.1101/640995Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systemsRecommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersConservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4]. References [1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton. | Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View | |

24 May 2023

Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approachLugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761When does seasonal reproduction evolve?Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer

Have you ever wondered why some species breed seasonally while others do not? You might think it is all down to lattitude and the harshness of winters but it turns out it is quite a bit more complicated than that. A consequence of this is that climate change may result in the evolution of the degree of seasonal reproduction, with some species perhaps becoming less seasonal and others more so even in the same habitat. Burtschell et al. (2023) investigated how various factors influence seasonal breeding by building an individual-based model of a baboon population from which they calculated the degree of seasonality for the fittest reproductive strategy. They then altered key aspects of their model to examine how these changes impacted the degree of seasonality in the reproductive strategy. What they found is fascinating. The degree of seasonality in reproductive strategy is expected to increase with increased seasonality in the environment, decreased food availability, increased energy expenditure, and how predictable resource availability is. Interestingly, neither female cycle length nor extrinsic infant mortality influenced the degree of seasonality in reproduction. What this means in reality for seasonal species is more challenging to understand. Some environments appear to be becoming more seasonal yet less predictable, and some species appear to be altering their daily energy budgets in response to changing climate in quite complex ways. As with pretty much everything in biology, Burtschell et al.'s work reveals much nuance and complexity, and that predicting how species might alter their reproductive timing is fraught with challenges. The paper is very well written. With a simpler model it may have proven possible to achieve analytical solutions, but this is a very minor gripe. The reviewers were positive about the paper, and I have little doubt it will be well-cited. REFERENCES Burtschell L, Dezeure J, Huchard E, Godelle B (2023) Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, 2022.08.22.504761, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761 | Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach | Lugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle | <p style="text-align: justify;">Reproductive seasonality is a major adaptation to seasonal cycles and varies substantially among organisms. This variation, which was long thought to reflect a simple latitudinal gradient, remains poorly understood ... |  | Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Theoretical ecology | Tim Coulson | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-23 21:37:28 | View |

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

17 May 2023

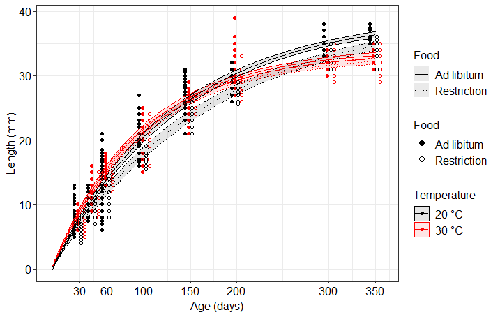

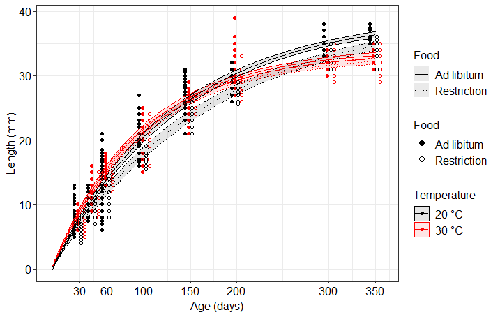

Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectothermsSimon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3Effect of food conditions on the Temperature-Size RuleRecommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Wilco VerberkTemperature-size rule (TSR) is a phenomenon of plastic changes in body size in response to temperature, originally observed in more than 80% of ectothermic organisms representing various groups (Atkinson 1994). In particular, ectotherms were observed to grow faster and reach smaller size at higher temperature and grow slower and achieve larger size at lower temperature. This response has fired the imagination of researchers since its invention, due to its counterintuitive pattern from an evolutionary perspective (Berrigan and Charnov 1994). The main question to be resolved is: why do organisms grow fast and achieve smaller sizes under more favourable conditions (= relatively higher temperature), while they grow longer and achieve larger sizes under less favourable conditions (relatively lower temperature), if larger size means higher fitness, while longer development may be risky? This evolutionary conundrum still awaits an ultimate explanation (Angilletta Jr et al. 2004; Angilletta and Dunham 2003; Verberk et al. 2021). Although theoretical modelling has shown that such a growth pattern can be achieved as a response to temperature alone, with a specific combination of energetic parameters and external mortality (Kozłowski et al. 2004), it has been suggested that other temperature-dependent environmental variables may be the actual drivers of this pattern. One of the most frequently invoked variable is the relative oxygen availability in the environment (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2006; Audzijonyte et al. 2019; Verberk et al. 2021; Woods 1999), which decreases with temperature increase. Importantly, this effect is more pronounced in aquatic systems (Forster et al. 2012). However, other temperature-dependent parameters are also being examined in the context of their possible effect on TSR induction and strength. Food availability is among the interfering factors in this regard. In aquatic systems, nutritional conditions are generally better at higher temperature, while a range of relatively mild thermal conditions is considered. However, there are no conclusive results so far on how nutritional conditions affect the plastic body size response to acute temperature changes. A study by Bazin et al. (2023) examined this particular issue, the effects of food and temperature on TSR, in medaka fish. An important value of the study was to relate the patterns found to fitness. This is a rare and highly desirable approach since evolutionary significance of any results cannot be reliably interpreted unless shown as expressed in light of fitness. The authors compared the body size of fish kept at 20°C and 30°C under conditions of food abundance or food restriction. The results showed that the TSR (smaller body size at 30°C compared to 20°C) was observed in both food treatments, but the effect was delayed during fish development under food restriction. Regarding the relevance to fitness, increased temperature resulted in more eggs laid but higher mortality, while food restriction increased survival but decreased the number of eggs laid in both thermal treatments. Overall, food restriction seemed to have a more severe effect on development at 20°C than at 30°C, contrary to the authors’ expectations. I found this result particularly interesting. One possible interpretation, also suggested by the authors, is that the relative oxygen availability, which was not controlled for in this study, could have affected this pattern. According to theoretical predictions confirmed in quite many empirical studies so far, oxygen restriction is more severe at higher temperatures. Perhaps for these particular two thermal treatments and in the case of the particular species studied, this restriction was more severe for organismal performance than the food restriction. This result is an example that all three variables, temperature, food and oxygen, should be taken into account in future studies if the interrelationship between them is to be understood in the context of TSR. It also shows that the reasons for growing smaller in warm may be different from those for growing larger in cold, as suggested, directly or indirectly, in some previous studies (Hessen et al. 2010; Leiva et al. 2019). Since medaka fish represent predatory vertebrates, the results of the study contribute to the issue of global warming effect on food webs, as the authors rightly point out. This is an important issue because the general decrease in the size or organisms in the aquatic environment with global warming is a fact (e.g., Daufresne et al. 2009), while the question of how this might affect entire communities is not trivial to resolve (Ohlberger 2013). REFERENCES Angilletta Jr, M. J., T. D. Steury & M. W. Sears, 2004. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life–history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44:498-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498 Angilletta, M. J. & A. E. Dunham, 2003. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: Simple evolutionary explanations may not be general. American Naturalist 162(3):332-342. https://doi.org/10.1086/377187 Atkinson, D., 1994. Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms. Advances in Ecological Research 25:1-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3 Atkinson, D., S. A. Morley & R. N. Hughes, 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply? Evolution & Development 8(2):202-214 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x Audzijonyte, A., D. R. Barneche, A. R. Baudron, J. Belmaker, T. D. Clark, C. T. Marshall, J. R. Morrongiello & I. van Rijn, 2019. Is oxygen limitation in warming waters a valid mechanism to explain decreased body sizes in aquatic ectotherms? Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(2):64-77 https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12847 Bazin, S., Hemmer-Brepson, C., Logez, M., Sentis, A. & Daufresne, M. 2023. Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms. HAL, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3 Berrigan, D. & E. L. Charnov, 1994. Reaction norms for age and size at maturity in response to temperature – a puzzle for life historians. Oikos 70:474-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545787 Daufresne, M., K. Lengfellner & U. Sommer, 2009. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106(31):12788-93 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902080106 Forster, J., A. G. Hirst & D. Atkinson, 2012. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(47):19310-19314. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210460109 Hessen, D. O., P. D. Jeyasingh, M. Neiman & L. J. Weider, 2010. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004 Kozłowski, J., M. Czarnoleski & M. Dańko, 2004. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold? Integrative and Comparative Biology 44(6):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.480 Leiva, F. P., P. Calosi & W. C. E. P. Verberk, 2019. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374:20190035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0035 Ohlberger, J., 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body szie - from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12098 Verberk, W. C. E. P., D. Atkinson, K. N. Hoefnagel, A. G. Hirst, C. R. Horne & H. Siepel, 2021. Shrinking body sizes in response to warming: explanations for the temperature-size rule with special emphasis on the role of oxygen. Biological Reviews 96:247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12653 Woods, H. A., 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. American Zoologist 39:244-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.2.244 | Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms | Simon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne | <p>The reduction of body size with warming has been proposed as the third universal response to global warming, besides geographical and phenological shifts. Observed body size shifts in ectotherms are mostly attributed to the temperature size rul... |  | Climate change, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2022-07-27 09:28:29 | View | |

01 Oct 2023

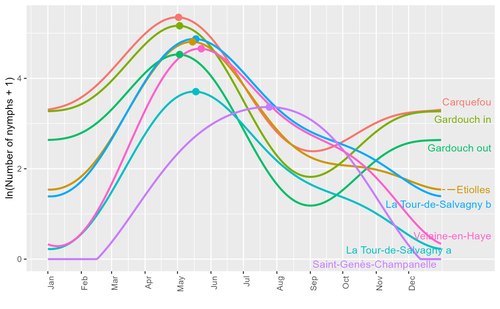

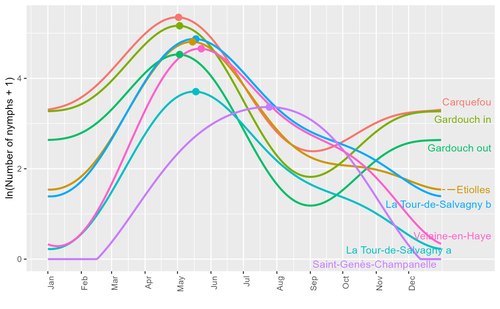

Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climateThierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Verheyden, Gwenaёl Vourc’h, Karine Chalvet-Monfray, Albert Agoulon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416Assessing seasonality of tick abundance in different climatic regionsRecommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne pathogens are considered as one of the major threats to public health – Lyme borreliosis being a well-known example of such disease. Global change – from climate change to changes in land use or invasive species – is playing a role in the increased risk associated with these pathogens. An important aspect of our knowledge of ticks and their associated pathogens is seasonality – one component being the phenology of within-year tick occurrences. This is important both in terms of health risk – e.g., when is the risk of encountering ticks high – and ecological understanding, as tick dynamics may depend on the weather as well as different hosts with their own dynamics and habitat use. Hoch et al. (2023) provide a detailed data set on the phenology of one species of tick, Ixodes ricinus, in 6 different locations of France. Whereas relatively cool sites showed a clear peak in spring-summer, warmer sites showed in addition relatively high occurrences in fall-winter, with a minimum in late summer-early fall. Such results add robust data to the existing evidence of the importance of local climatic patterns for explaining tick phenology. Recent analyses have shown that the phenology of Lyme borreliosis has been changing in northern Europe in the last 25 years, with seasonal peaks in cases occurring now 6 weeks earlier (Goren et al. 2023). The study by Hoch et al. (2023) is of too short duration to establish temporal changes in phenology (“only” 8 years, 2014-2021, see also Wongnak et al 2021 for some additional analyses; given the high year-to-year variability in weather, establishing phenological changes often require longer time series), and further work is needed to get better estimates of these changes and relate them to climate, land-use, and host density changes. Moreover, the phenology of ticks may also be related to species-specific tick phenology, and different tick species do not respond to current changes in identical ways (see for example differences between the two Ixodes species in Finland; Uusitalo et al. 2022). An efficient surveillance system requires therefore an adaptive monitoring design with regard to the tick species as well as the evolving causes of changes. References Goren, A., Viljugrein, H., Rivrud, I. M., Jore, S., Bakka, H., Vindenes, Y., & Mysterud, A. (2023). The emergence and shift in seasonality of Lyme borreliosis in Northern Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1993), 20222420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2420 Hoch, T., Madouasse, A., Jacquot, M., Wongnak, P., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Agoulon, A. (2023). Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climate. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416 Uusitalo, R., Siljander, M., Lindén, A., Sormunen, J. J., Aalto, J., Hendrickx, G., . . . Vapalahti, O. (2022). Predicting habitat suitability for Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Finland. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05410-8 Wongnak, P., Bord, S., Jacquot, M., Agoulon, A., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Chalvet-Monfray, K. (2022). Meteorological and climatic variables predict the phenology of Ixodes ricinus nymph activity in France, accounting for habitat heterogeneity. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11479-z | Seasonality of host-seeking *Ixodes ricinus* nymph abundance in relation to climate | Thierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Ve... | <p style="text-align: justify;">There is growing concern about climate change and its impact on human health. Specifically, global warming could increase the probability of emerging infectious diseases, notably because of changes in the geographic... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-10-14 18:43:56 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle