Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

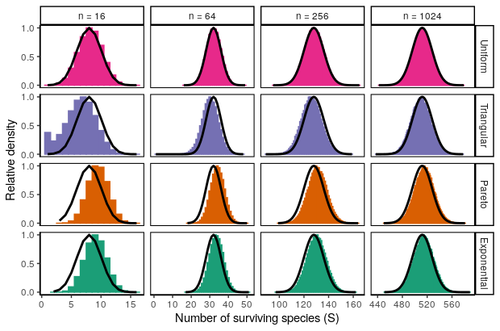

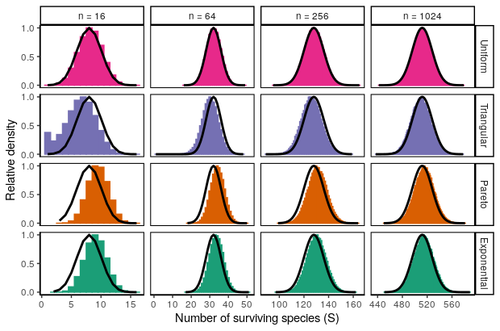

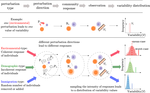

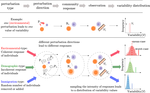

10 Aug 2023

Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-offZachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867Assembly in metacommunities driven by a competition-colonization tradeoff: more species in, more species outRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Canan Karakoç and 1 anonymous reviewerThe output of a community model depends on how you set its parameters. Thus, analyses of specific parameter settings hardwire the results to specific ecological scenarios. Because more general answers are often of interest, one tradition is to give models a statistical treatment: one summarizes how model parameters vary across species, and then predicts how changing the summary, instead of the individual parameters themselves, would change model output. Arguably the best-known example is the work initiated by May, showing that the properties of a community matrix, encoding effects species have on each other near their equilibrium, determine stability (1,2). More recently, this statistical treatment has also been applied to one of community ecology’s more prickly and slippery subjects: community assembly, which deals with the question “Given some regional species pool, which species will be able to persist together at some local ecosystem?”. Summaries of how species grow and interact in this regional pool predict the fraction of survivors and their relative abundances, the kind of dynamics, and various kinds of stability (3,4). One common characteristic of such statistical treatments is the assumption of disorder: if species do not interact in too structured ways, simple and therefore powerful predictions ensue that often stand up to scrutiny in relatively ordered systems. 2. Allesina, S. & Tang, S. (2015). The stability–complexity relationship at age 40: a random matrix perspective. Population Ecology, 57, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10144-014-0471-0 3. Bunin, G. (2016). Interaction patterns and diversity in assembled ecological communities. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.04734. 5. Miller, Z. R., Clenet, M., Libera, K. D., Massol, F. & Allesina, S. (2023). Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off. bioRxiv 2023.03.23.533867, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867 6. Serván, C. A. & Allesina, S. (2021). Tractable models of ecological assembly. Ecology Letters, 24, 1029–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13702 | Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off | Zachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina | <p>The competition-colonization trade-off is a well-studied coexistence mechanism for metacommunities. In this setting, it is believed that coexistence of all species requires their traits to satisfy restrictive conditions limiting their similarit... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Frederik De Laender | 2023-03-30 20:42:48 | View | |

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View | ||

27 Apr 2021

Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit fliesBenoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326Understanding the interplay between host-specificity, environmental conditions and competition through the sound application of Joint Species Distribution ModelsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann

Understanding why and how species coexist in local communities is one of the central questions in ecology. There is general agreement that species distribution and coexistence are determined by a number of key mechanisms, including the environmental requirements of species, dispersal, evolutionary constraints, resource availability and selection, metapopulation dynamics, and biotic interactions (e.g. Soberón & Nakamura 2009; Colwell & Rangel 2009; Ricklefs 2015). These factors are however intricately intertwined in a scale-structured fashion (Hortal et al. 2010; D’Amen et al. 2017), making it particularly difficult to tease apart the effects of each one of them. This could be addressed by the novel field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling (JSDM; Okasvainen & Abrego 2020), as it allows assessing the effects of several sets of factors and the co-occurrence and/or covariation in abundances of potentially interacting species at the same time (Pollock et al. 2014; Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Dormann et al. 2018). However, the development of JSDM has been hampered by the general lack of good-quality detailed data on species co-occurrences and abundances (see Hortal et al. 2015). Facon et al. (2021) use a particularly large compilation of field surveys to study the abundance and co-occurrence of Tephritidae fruit flies in c. 400 orchards, gardens and natural areas throughout the island of Réunion. Further, they combine such information with lab data on their host-selection fundamental niche (i.e. in the absence of competitors), codifying traits of female choice and larval performances in 21 host species. They use Poisson Log-Normal models, a type of mixed model that allows one to jointly model the random effects associated with all species, and retrieve the covariations in abundance that are not explained by environmental conditions or differences in sampling effort. Then, they use a series of models to evaluate the effects on these matrices of ecological covariates (date, elevation, habitat, climate and host plant), species interactions (by comparing with a constrained residual variance-covariance matrix) and the species’ host-selection fundamental niches (through separate models for each fly species). The eight Tephritidae species inhabiting Réunion include both generalists and specialists in Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae with a known history of interspecific competition. Facon et al. (2021) use a comprehensive JSDM approach to assess the effects of different factors separately and altogether. This allows them to identify large effects of plant hosts and the fundamental host-selection niche on species co-occurrence, but also to show that ecological covariates and weak –though not negligible– species interactions are necessary to account for all residual variance in the matrix of joint species abundances per site. Further, they also find evidence that the fitness per host measured in the lab has a strong influence on the abundances in each host plant in the field for specialist species, but not for generalists. Indeed, the stronger effects of competitive exclusion were found in pairs of Cucurbitaceae specialist species. However, these analyses fail to provide solid grounds to assess why generalists are rarely found in Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae. Although they argue that this may be due to Connell’s (1980) ghost of competition past (past competition that led to current niche differentiation), further data on the evolutionary history of these fruit flies is needed to assess this hypothesis. Finding evidence for the effects of competitive interactions on species’ occurrences and spatial distributions is often difficult, perhaps because these effects occur over longer time scales than the ones usually studied by ecologists (Yackulic 2017). The work by Facon and colleagues shows that weak effects of competition can be detected also at the short ecological timescales that determine coexistence in local communities, under the virtuous combination of good-quality data and sound analytical designs that account for several aspects of species’ niches, their biotopes and their joint population responses. This adds a new dimension to the application of Hutchinson’s (1978) niche framework to understand the spatial dynamics of species and communities (see also Colwell & Rangel 2009), although further advances to incorporate dispersal-driven metacommunity dynamics (see, e.g., Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Leibold et al. 2017) are certainly needed. Nonetheless, this work shows the potential value of in-depth analyses of species coexistence based on combining good-quality field data with well-thought out JSDM applications. If many studies like this are conducted, it is likely that the uprising field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling will improve our understanding of the hierarchical relationships between the different factors affecting species coexistence in ecological communities in the near future.

References Colwell RK, Rangel TF (2009) Hutchinson’s duality: The once and future niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19651–19658. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901650106 Connell JH (1980) Diversity and the Coevolution of Competitors, or the Ghost of Competition Past. Oikos, 35, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 D’Amen M, Rahbek C, Zimmermann NE, Guisan A (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Dormann CF, Bobrowski M, Dehling DM, Harris DJ, Hartig F, Lischke H, Moretti MD, Pagel J, Pinkert S, Schleuning M, Schmidt SI, Sheppard CS, Steinbauer MJ, Zeuss D, Kraan C (2018) Biotic interactions in species distribution modelling: 10 questions to guide interpretation and avoid false conclusions. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27, 1004–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759 Facon B, Hafsi A, Masselière MC de la, Robin S, Massol F, Dubart M, Chiquet J, Frago E, Chiroleu F, Duyck P-F, Ravigné V (2021) Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of community structure in fruit flies. bioRxiv, 2020.12.07.414326. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326 Hortal J, de Bello F, Diniz-Filho JAF, Lewinsohn TM, Lobo JM, Ladle RJ (2015) Seven Shortfalls that Beset Large-Scale Knowledge of Biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46, 523–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054400 Hortal J, Roura‐Pascual N, Sanders NJ, Rahbek C (2010) Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 33, 51–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06428.x Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Leibold MA, Chase JM, Ernest SKM (2017) Community assembly and the functioning of ecosystems: how metacommunity processes alter ecosystems attributes. Ecology, 98, 909–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1697 Ovaskainen O, Abrego N (2020) Joint Species Distribution Modelling: With Applications in R. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108591720 Ovaskainen O, Roy DB, Fox R, Anderson BJ (2016) Uncovering hidden spatial structure in species communities with spatially explicit joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12502 Pollock LJ, Tingley R, Morris WK, Golding N, O’Hara RB, Parris KM, Vesk PA, McCarthy MA (2014) Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180 Ricklefs RE (2015) Intrinsic dynamics of the regional community. Ecology Letters, 18, 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12431 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Yackulic CB (2017) Competitive exclusion over broad spatial extents is a slow process: evidence and implications for species distribution modeling. Ecography, 40, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02836 | Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit flies | Benoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné | <p style="text-align: justify;">The relative importance of ecological factors and species interactions for phytophagous insect species distributions has long been a controversial issue. Using field abundances of eight sympatric Tephritid fruit fli... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | Carsten Dormann, Joaquín Calatayud | 2020-12-08 06:44:25 | View |

01 Apr 2019

The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patternsJean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman https://doi.org/10.1101/431296Diversity-Stability and the Structure of PerturbationsRecommended by Kevin Cazelles and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer

In his 1972 paper “Will a Large Complex System Be Stable?” [1], May challenges the idea that large communities are more stable than small ones. This was the beginning of a fundamental debate that still structures an entire research area in ecology: the diversity-stability debate [2]. The most salient strength of May’s work was to use a mathematical argument to refute an idea based on the observations that simple communities are less stable than large ones. Using the formalism of dynamical systems and a major results on the distribution of the eigen values for random matrices, May demonstrated that the addition of random interactions destabilizes ecological communities and thus, rich communities with a higher number of interactions should be less stable. But May also noted that his mathematical argument holds true only if ecological interactions are randomly distributed and thus concluded that this must not be true! This is how the contradiction between mathematics and empirical observations led to new developments in the study of ecological networks. References [1] May, Robert M (1972). Will a Large Complex System Be Stable? Nature 238, 413–414. doi: 10.1038/238413a0 | The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patterns | Jean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman | <p>Empirical knowledge of ecosystem stability and diversity-stability relationships is mostly based on the analysis of temporal variability of population and ecosystem properties. Variability, however, often depends on external factors that act as... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Kevin Cazelles | 2018-10-02 14:01:03 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

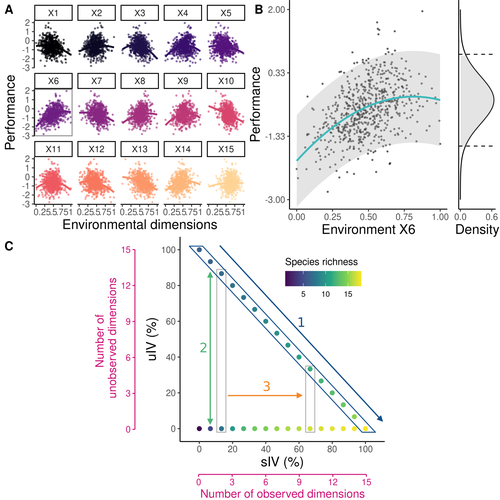

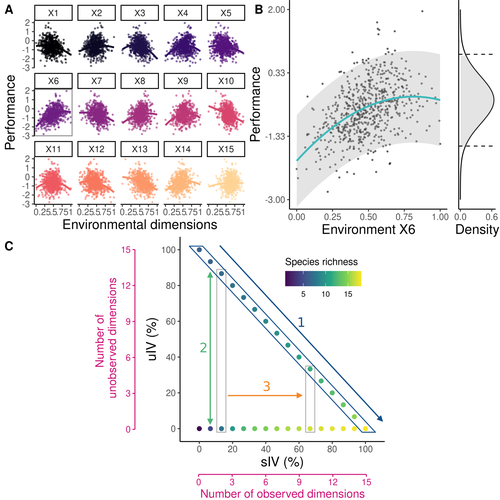

Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structureCamille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032Two paradigms for intraspecific variabilityRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman

Community ecology usually concerns itself with understanding the causes and consequences of diversity at a given taxonomic resolution, most classically at the species level. Yet there is no doubt that diversity exists at all scales, and phenotypic variability within a taxon can be comparable to differences between taxa, as observed from bacteria to fish and trees. The question that motivates an active and growing body of work (e.g. Raffard et al 2019) is not so much whether intraspecific variability matters, but what we get wrong by ignoring it and how to incorporate it into our understanding of communities. There is no established way to think about diversity at multiple nested taxonomic levels, and it is tempting to summarize intraspecific variability simply by measuring species mean and variance in any trait and metric. In this study, Girard-Tercieux et al (2023a) propose that, to understand its impact on community-level outcomes and in particular on species coexistence, we should carefully distinguish between two ways of thinking about intraspecific variability: -"unstructured" variation, where every individual's features are like an independent random draw from a species-specific distribution, for instance, due to genetic lottery and developmental accidents -"structured" variation that is due to each individual encountering a different but enduring microenvironment. The latter type of variability may still appear complex and random-like when the environment is high-dimensional (i.e. multifaceted, with many different factors contributing to each individual's performance and development). Thus, it is not necessarily "structured" in the sense of being easily understood -- we may need to measure more aspects of the environment than is practical if we want to fully predict these variations. What distinguishes this "structured" variability is that it is, in a loose sense, inheritable: individuals from the same species that grow in the same microenvironment will have the same performance, in a repeatable fashion. Thus, if each species is best at exploiting at least a fraction of environmental conditions, it is likely to avoid extinction by competition, except in the unlucky case of no propagule reaching any of the favorable sites. The core intuition, that the complex spatial structure and high-dimensional nature of the environment plays a key explanatory role in species coexistence, is a running thread through several of the authors' work (e.g. Clark et al 2010), clearly inspired by their focus on tropical forests. This study, by tackling the question of intraspecific determinants of interspecific outcomes, makes a compelling addition to this line of investigation, coming as a theoretical companion to a more data-oriented study (Girard-Tercieux et al 2023b). But I believe it raises a question that is even broader in scope. This kind of intraspecific variability, due to different individuals growing in different microenvironments, is perhaps most relevant for trees and other sessile organisms, but the distinction made here between "unstructured" and "structured" variability can likely be extended to many other ecological settings. In my understanding, what matters most in "structured" variability is not so much it stemming from a fixed environment, but rather it being maintained across generations, rather than possibly lost by drift. This difference between variability in the form of "frozen" randomness and in the form of stochastic drift over time is highly relevant in other theoretical fields (e.g. in physics, where it is the difference between a disordered solid and a liquid), and thus, I expect that it is a meaningful distinction to make throughout community ecology. References James S. Clark, David Bell, Chengjin Chu, Benoit Courbaud, Michael Dietze, Michelle Hersh, Janneke HilleRisLambers et al. (2010) "High‐dimensional coexistence based on individual variation: a synthesis of evidence." Ecological Monographs 80, no. 4 : 569-608. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1541.1 Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux (2023a) "Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure." bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032 Camille Girard‐Tercieux, Isabelle Maréchaux, Adam T. Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Joannès Guillemot et al. (2023b) "Rethinking the nature of intraspecific variability and its consequences on species coexistence." Ecology and Evolution 13, no. 3 : e9860. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9860 Allan Raffard, Frédéric Santoul, Julien Cucherousset, and Simon Blanchet. (2019) "The community and ecosystem consequences of intraspecific diversity: A meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 94, no. 2: 648-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12472 | Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure | Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux | <p>The role of intraspecific variability (IV) in shaping community dynamics and species coexistence has been intensively discussed over the past decade and modelling studies have played an important role in that respect. However, these studies oft... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2022-08-07 12:51:30 | View | |

21 Nov 2023

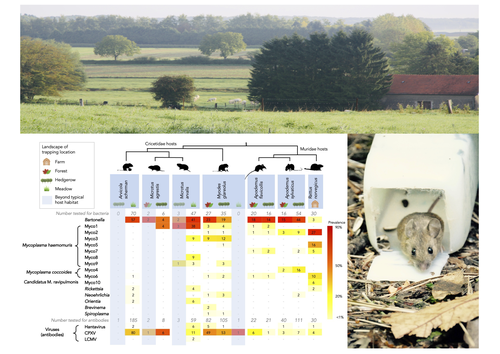

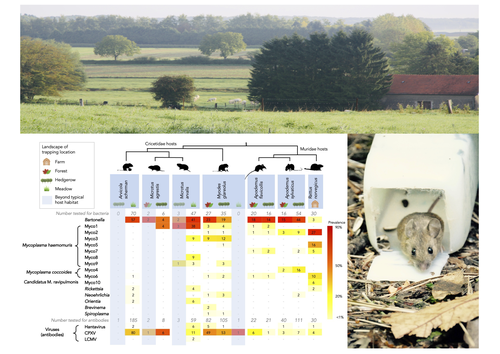

Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodentsJessica Lee Abbate, Maxime Galan, Maria Razzauti, Tarja Sironen, Liina Voutilainen, Heikki Henttonen, Patrick Gasqui, Jean-François Cosson, Nathalie Charbonnel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.09.940494Reservoirs of pestilence: what pathogen and rodent community analyses can tell us about transmission riskRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Adrian Diaz, Romain Pigeault and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Adrian Diaz, Romain Pigeault and 1 anonymous reviewer

Rodents are well known as one of the main animal groups responsible for human-transmitted pathogens. As such, it seems logical to try and survey what kinds of pathogenic microbes might be harboured by wild rodents, in order to establish some baseline surveillance and prevent future zoonotic outbreaks (Bernstein et al., 2022). This is exactly what Abbate et al. (2023) endeavoured and their findings are intimidating. Based on quite a large sampling effort, they collected more than 700 rodents of seven species around two villages in northeastern France. They looked for molecular markers indicative of viral and bacterial infections and proceeded to analyze their pathogen communities using multivariate techniques. Variation in the prevalence of the different pathogens was found among host species, with e.g. signs of CPXV more prevalent in Cricetidae while some Mycoplasma strains were more prevalent in Muridae. Co-circulation of pathogens was found in all species, with some evidencing signs of up to 12 different pathogen taxa. The diversity of co-circulating pathogens was markedly different between host species and higher in adult hosts, but not affected by sex. The dataset also evinced some slight differences between habitats, with meadows harbouring a little more diversity of rodent pathogens than forests. Less intuitively, some pathogen associations seemed quite repeatable, such as the positive association of Bartonella spp. with CPXV in the montane water vole. The study allowed the authors to test several associations already described in the literature, including associations between different hemotropic Mycoplasma species. I strongly invite colleagues interested in zoonoses, emerging pandemics and more generally One Health to read the paper of Abbate et al. (2023) and try to replicate them across the world. To prevent the next sanitary crises, monitoring rodents, and more generally vertebrates, population demographics is a necessary and enlightening step (Johnson et al., 2020), but insufficient. Following the lead of colleagues working on rodent ectoparasites (Krasnov et al., 2014), we need more surveys like the one described by Abbate et al. (2023) to understand the importance of the dilution effect in the prevalence and transmission of microbial pathogens (Andreazzi et al., 2023) and the formation of epidemics. We also need other similar studies to assess the potential of different rodent species to carry pathogens more or less capable of infecting other mammalian species (Morand et al., 2015), in other places in the world. References Abbate, J. L., Galan, M., Razzauti, M., Sironen, T., Voutilainen, L., Henttonen, H., Gasqui, P., Cosson, J.-F. & Charbonnel, N. (2023) Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodents. BioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.09.940494 Andreazzi, C. S., Martinez-Vaquero, L. A., Winck, G. R., Cardoso, T. S., Teixeira, B. R., Xavier, S. C. C., Gentile, R., Jansen, A. M. & D'Andrea, P. S. (2023) Vegetation cover and biodiversity reduce parasite infection in wild hosts across ecological levels and scales. Ecography, 2023, e06579. | Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodents | Jessica Lee Abbate, Maxime Galan, Maria Razzauti, Tarja Sironen, Liina Voutilainen, Heikki Henttonen, Patrick Gasqui, Jean-François Cosson, Nathalie Charbonnel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Rodents are major reservoirs of pathogens that can cause disease in humans and livestock. It is therefore important to know what pathogens naturally circulate in rodent populations, and to understand the factors tha... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology, Species distributions | Francois Massol | 2020-02-11 12:42:28 | View | |

06 Sep 2019

Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community compositionFranck Jabot, Fabien Laroche, Francois Massol, Florent Arthaud, Julie Crabot, Maxime Dubart, Simon Blanchet, Francois Munoz, Patrice David, Thibault Datry https://doi.org/10.1101/480335On the importance of temporal meta-community dynamics for our understanding of assembly processesRecommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Joaquín Hortal and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Joaquín Hortal and 2 anonymous reviewers

The processes that trigger community assembly are still in the centre of ecological interest. While prior work mostly focused on spatial patterns of co-occurrence within a meta-community framework [reviewed in 1, 2] recent studies also include temporal patterns of community composition [e.g. 3, 4, 5, 6]. In this preprint [7], Franck Jabot and co-workers extend they prior approaches to quasi neutral community assembly [8, 9, 10] and develop an analytical framework of spatial and temporal diversity turnover. A simple and heuristic path model for beta diversity and an extended ecological drift model serve as starting points. The model can be seen as a counterpart to Ulrich et al. [5]. These authors implemented competitive hierarchies into their neutral meta-community model while the present paper focuses on environmental filtering. Most important, the model and parameterization of four empirical data sets on aquatic plant and animal meta-communities used by Jabot et al. returned a consistent high influence of environmental stochasticity on species turnover. Of course, this major result does not come to a surprise. As typical for this kind of models it depends also to a good deal on the initial model settings. It nevertheless makes a strong conceptual point for the importance of environmental variability over dispersal and richness effects. One interesting side effect regards the impact of richness differences (ΔS). Jabot et al. interpret this as a ‘nuisance variable’ as they do not have a stringent explanation. Of course, it might be a pure statistical bias introduced by the Soerensen metric of turnover that is normalized by richness. However, I suspect that there is more behind the ΔS effect. Richness differences are generally associated with respective differences in total abundances and introduce source – sink dynamics that inevitably shape subsequent colonization – extinction processes. It would be interesting to see whether ΔS alone is able to trigger observed patterns of community assembly and community composition. Such an analysis would require partitioning of species turnover into richness and nestedness effects [11]. I encourage Jabot et al. to undertake such an effort. References [1] Götzenberger, L. et al. (2012). Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological reviews, 87(1), 111-127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00187.x | Assessing metacommunity processes through signatures in spatiotemporal turnover of community composition | Franck Jabot, Fabien Laroche, Francois Massol, Florent Arthaud, Julie Crabot, Maxime Dubart, Simon Blanchet, Francois Munoz, Patrice David, Thibault Datry | <p>Although metacommunity ecology has been a major field of research in the last decades, with both conceptual and empirical outputs, the analysis of the temporal dynamics of metacommunities has only emerged recently and still consists mostly of r... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Werner Ulrich | 2018-11-29 14:58:54 | View | |

29 Aug 2023

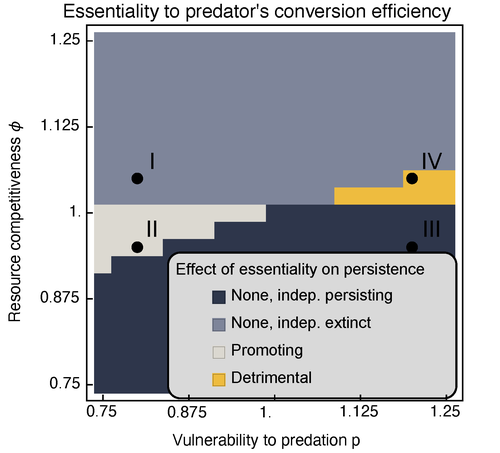

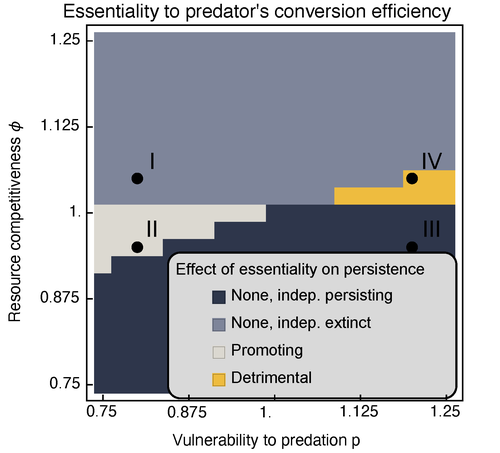

Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food websMichael Raatz https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839High-order interactions in food webs may strongly impact persistence of speciesRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer

Michael Raatz (2023) provides here a relevant exploration of higher-order interactions, i.e. interactions involving more than two related species (Terry et al. 2019), in the case of food web and competition interactions. More precisely, he shows by modeling that essential resources may significantly mediate focal species' persistence. Simultaneously, the provision of essential resources may strongly affect the resulting community structure, by driving to extinction first the predator and then, depending on the higher-order interaction, potentially also the associated competitor. Today, all ecologists should be aware of the potential effects of high-order interactions on species' (and likely on ecosystem's) fate (Golubski et al. 2016, Grilli et al. 2017). Yet, we should soon be prepared to include any high-order interaction into any interaction network (i.e. not only between species, but also between species and abiotic components, and between biotic, anthropogenic and abiotic components too). For this purpose, we will need innovative approaches such as hypergraphs (Golubski et al. 2016) and discrete-event models (Gaucherel and Pommereau 2019, Thomas et al. 2022) able to manage highly complex interactions, with numerous interacting components and variables. Such a rigorous study is a necessary and preliminary step in taking into account such a higher complexity. References Gaucherel, C. and F. Pommereau. 2019. Using discrete systems to exhaustively characterize the dynamics of an integrated ecosystem. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 00:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13242 Golubski, A. J., E. E. Westlund, J. Vandermeer, and M. Pascual. 2016. Ecological Networks over the Edge: Hypergraph Trait-Mediated Indirect Interaction (TMII) Structure trends in Ecology & Evolution 31:344-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.006 Grilli, J., G. Barabas, M. J. Michalska-Smith, and S. Allesina. 2017. Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature 548:210-213. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23273 Raatz, M. 2023. Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839 Terry, J. C. D., R. J. Morris, and M. B. Bonsall. 2019. Interaction modifications lead to greater robustness than pairwise non-trophic effects in food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 88:1732-1742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13057 Thomas, C., M. Cosme, C. Gaucherel, and F. Pommereau. 2022. Model-checking ecological state-transition graphs. PLoS Computational Biology 18:e1009657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009657 | Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs | Michael Raatz | <p style="text-align: justify;">Pairwise interactions in food webs, including those between predator and prey are often modulated by a third species. Such higher-order interactions are important structural components of natural food webs that can ... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Competition, Ecological stoichiometry, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | 2023-02-23 17:48:26 | View | |

06 Nov 2023

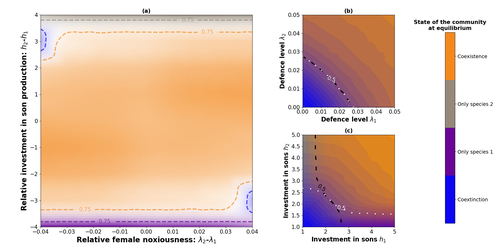

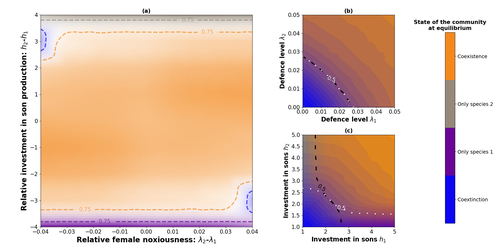

Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approachMaxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153Mullerian and Batesian mimicry can influence population and community dynamicsRecommended by Amanda Franklin based on reviews by Jesus Bellver and 1 anonymous reviewerMimicry between species has long attracted the attention of scientists. Over a century ago, Bates first proposed that palatable species should gain a benefit by resembling unpalatable species (Bates 1862). Not long after, Müller suggested that there could also be a mutual advantage for two unpalatable species to mimic one another to reduce predator error (Müller 1879). These forms of mimicry, Batesian and Müllerian, are now widely studied, providing broad insights into behaviour, ecology and evolution. Numerous taxa, including both invertebrates and vertebrates, show examples of Batesian or Müllerian mimicry. Bees and wasps provide a particularly interesting case due to the differences in defence between females and males of the same species. While both males and females may display warning colours, only females can sting and inject venom to cause pain and allow escape from predators. Therefore, males are palatable mimics and can resemble females of their own species or females of another species (dual sex-limited mimicry). This asymmetry in defence could have impacts on both population structure and community assembly, yet research into mimicry largely focuses on systems without sex differences. Here, Boutin and colleagues (2023) use a differential equations model to explore the effect of mimicry on population structure and community assembly for sex-limited defended species. Specifically, they address three questions, 1) how do female noxiousness and sex-ratio influence the extinction risk of a single species?; 2) what is the effect of mimicry on species co-existence? and 3) how does dual sex-limited mimicry influence species co-existence? Their results reveal contexts in which populations with undefended males can persist, the benefit of Müllerian mimicry for species coexistence and that dual sex-limited mimicry can have a destabilising impact on species coexistence. The results not only contribute to our understanding of how mimicry is maintained in natural systems but also demonstrate how changes in relative abundance or population structure of one species could impact another species. Further insight into the population and community dynamics of insects is particularly important given the current population declines (Goulson 2019; Seibold et al 2019). References Bates, H. W. 1862. Contributions to the insect fauna of the Amazon Valley, Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23:495- 566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x Boutin, M., Costa, M., Fontaine, C., Perrard, A., Llaurens, V. 2022 Influence of sex-limited mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153 Goulson, D. 2019. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Curr. Biol. 29: R967-R971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.069 Müller, F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia; a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Roy. Entom. Roc. 1879:20-29. Seibold, S., Gossner, M. M., Simons, N. K., Blüthgen, N., Müller, J., Ambarlı, D., ... & Weisser, W. W. 2019. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature, 574: 671-674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1684-3 | Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach | Maxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens | <p style="text-align: justify;">Positive ecological interactions, such as mutualism, can play a role in community structure and species co-existence. A well-documented case of mutualistic interaction is Mullerian mimicry, the convergence of colour... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism | Amanda Franklin | 2022-10-25 19:11:55 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheriesEric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905“Hidden” natural selection and the evolution of body size in harvested stocksRecommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are exploiting biological resources since thousands of years. Exploitation of biological resources has become particularly intense since the beginning of the 20th century and the steep increase in the worldwide human population size. Marine and freshwater fishes are not exception to that rule, and they have been (and continue to be) strongly harvested as a source of proteins for humans. For some species, fishery has been so intense that natural stocks have virtually collapsed in only a few decades. The worst example begin that of the Northwest Atlantic cod that has declined by more than 95% of its historical biomasses in only 20-30 years of intensive exploitation (Frank et al. 2005). These rapid and steep changes in biomasses have huge impacts on the entire ecosystems since species targeted by fisheries are often at the top of trophic chains (Frank et al. 2005). Beyond demographic impacts, fisheries also have evolutionary impacts on populations, which can also indirectly alter ecosystems (Uusi-Heikkilä et al. 2015; Palkovacs et al. 2018). Fishermen generally focus on the largest specimens, and hence exert a strong selective pressure against these largest fish (which is called “harvest selection”). There is now ample evidence that harvest selection can lead to rapid evolutionary changes in natural populations toward small individuals (Kuparinen & Festa-Bianchet 2017). These evolutionary changes are of course undesirable from a human perspective, and have attracted many scientific questions. Nonetheless, the consequence of harvest selection is not always observable in natural populations, and there are cases in which no phenotypic change (or on the contrary an increase in mean body size) has been observed after intense harvest pressures. In a conceptual Essay, Edeline and Loeuille (Edeline & Loeuille 2020) propose novel ideas to explain why the evolutionary consequences of harvest selection can be so diverse, and how a cross talk between ecological and evolutionary dynamics can explain patterns observed in natural stocks. The general and novel concept proposed by Edeline and Loeuille is actually as old as Darwin’s book; The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It is based on the simple idea that natural selection acting on harvested populations can actually be strong, and counter-balance (or on the contrary reinforce) the evolutionary consequence of harvest selection. Although simple, the idea that natural and harvest selection are jointly shaping contemporary evolution of exploited populations lead to various and sometimes complex scenarios that can (i) explain unresolved empirical patterns and (ii) refine predictions regarding the long-term viability of exploited populations. The Edeline and Loeuille’s crafty inspiration is that natural selection acting on exploited populations is itself an indirect consequence of harvest (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). They suggest that, by modifying the size structure of populations (a key parameter for ecological interactions), harvest indirectly alters interactions between populations and their biotic environment through competition and predation, which changes the ecological theatre and hence the selective pressures acting back to populations. They named this process “size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedback loops” and develop several scenarios in which these feedback loops ultimately deviate the evolutionary outcome of harvest selection from expectation. The scenarios they explore are based on strong theoretical knowledge, and range from simple ones in which a single species (the harvest species) is evolving to more complex (and realistic) ones in which multiple (e.g. the harvest species and its prey) species are co-evolving. I will not come into the details of each scenario here, and I will let the readers (re-)discovering the complex beauty of biological life and natural selection. Nonetheless, I will emphasize the importance of considering these eco-evolutionary processes altogether to fully grasp the response of exploited populations. Edeline and Loeuille convincingly demonstrate that reduced body size due to harvest selection is obviously not the only response of exploited fish populations when natural selection is jointly considered (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). On the contrary, they show that –under some realistic ecological circumstances relaxing exploitative competition due to reduced population densities- natural selection can act antagonistically, and hence favour stable body size in exploited populations. Although this seems further desirable from a human perspective than a downsizing of exploited populations, it is actually mere window dressing as Edeline and Loeuille further showed that this response is accompanied by an erosion of the evolvability –and hence a lowest probability of long-term persistence- of these exploited populations. Humans, by exploiting biological resources, are breaking the relative equilibrium of complex entities, and the response of populations to this disturbance is itself often complex and heterogeneous. In this Essay, Edeline and Loeuille provide –under simple terms- the theoretical and conceptual bases required to improve predictions regarding the evolutionary responses of natural populations to exploitation by humans (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). An important next step will be to generate data and methods allowing confronting the empirical reality to these novel concepts (e.g. (Monk et al. 2021), so as to identify the most likely evolutionary scenarios sustaining biological responses of exploited populations, and hence to set the best management plans for the long-term sustainability of these populations. References Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. John Murray, London. Edeline, E. & Loeuille, N. (2021) Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries. bioRxiv, 2020.04.03.022905, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905 Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J. S. & Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem. Science, 308, 1621–1623. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113075 Kuparinen, A. & Festa-Bianchet, M. (2017). Harvest-induced evolution: insights from aquatic and terrestrial systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 372, 20160036. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0036 Monk, C.T., Bekkevold, D., Klefoth, T., Pagel, T., Palmer, M. & Arlinghaus, R. (2021). The battle between harvest and natural selection creates small and shy fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2009451118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009451118 Palkovacs, E.P., Moritsch, M.M., Contolini, G.M. & Pelletier, F. (2018). Ecology of harvest-driven trait changes and implications for ecosystem management. Front. Ecol. Environ., 16, 20–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1743 Uusi-Heikkilä, S., Whiteley, A.R., Kuparinen, A., Matsumura, S., Venturelli, P.A., Wolter, C., et al. (2015). The evolutionary legacy of size-selective harvesting extends from genes to populations. Evol. Appl., 8, 597–620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12268 | Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries | Eric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Harvesting may drive body downsizing along with population declines and decreased harvesting yields. These changes are commonly construed as direct consequences of harvest selection, where small-bodied, early-reproducing individuals are immedia... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Competition, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Food webs, Interaction networks, Life history, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2020-04-03 16:14:05 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle