Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

05 Nov 2019

Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population.Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. https://doi.org/10.1101/474874Defoliation induces a trade-off between reproduction and growth in a southern population of BeechRecommended by Georges Kunstler based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIndividuals ability to withstand abiotic and biotic stresses is crucial to the maintenance of populations at climate edge of tree species distribution. We start to have a detailed understanding of tree growth response and to a lesser extent mortality response in these populations. In contrast, our understanding of the response of tree fecundity and recruitment remains limited because of the difficulty to monitor it at the individual tree level in the field. Tree recruitment limitation is, however, crucial for tree population dynamics [1-2]. References [1] Clark, J. S. et al. (1999). Interpreting recruitment limitation in forests. American Journal of Botany, 86(1), 1-16. doi: 10.2307/2656950 | Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population. | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. | <p>1. Although droughts and heatwaves have been associated to increased crown defoliation, decreased growth and a higher risk of mortality in many forest tree species, their impact on tree reproduction and forest regeneration still remains underst... |  | Climate change, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Molecular ecology, Physiology, Population ecology | Georges Kunstler | 2018-11-20 13:29:42 | View | |

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora coralsK. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza https://doi.org/10.1101/398602Transcriptomics of thermal stress response in coralsRecommended by Staffan Jacob based on reviews by Mar SobralClimate change presents a challenge to many life forms and the resulting loss of biodiversity will critically depend on the ability of organisms to timely respond to a changing environment. Shifts in ecological parameters have repeatedly been attributed to global warming, with the effectiveness of these responses varying among species [1, 2]. Organisms do not only have to face a global increase in mean temperatures, but a complex interplay with another crucial but largely understudied aspect of climate change: thermal fluctuations. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adaptation to thermal fluctuations is thus a timely and critical challenge. References [1] Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286 | Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora corals | K. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza | <p>Ecosystems worldwide are suffering from climate change. Coral reef ecosystems are globally threatened by increasing sea surface temperatures. However, gene expression plasticity provides the potential for organisms to respond rapidly and effect... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Symbiosis | Staffan Jacob | 2018-08-29 10:46:55 | View | |

17 May 2023

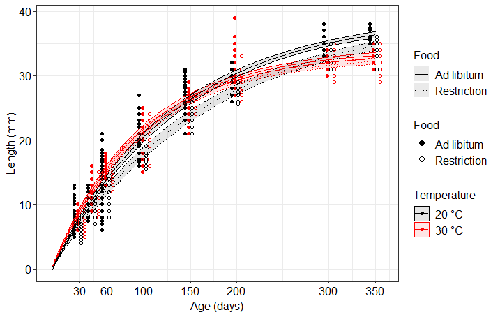

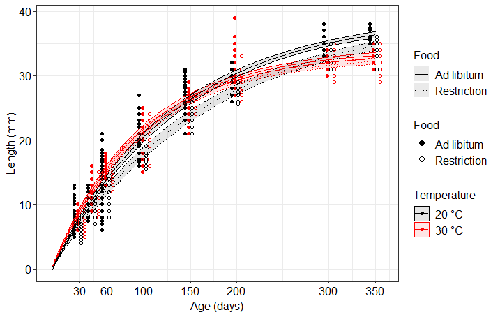

Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectothermsSimon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3Effect of food conditions on the Temperature-Size RuleRecommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Wilco VerberkTemperature-size rule (TSR) is a phenomenon of plastic changes in body size in response to temperature, originally observed in more than 80% of ectothermic organisms representing various groups (Atkinson 1994). In particular, ectotherms were observed to grow faster and reach smaller size at higher temperature and grow slower and achieve larger size at lower temperature. This response has fired the imagination of researchers since its invention, due to its counterintuitive pattern from an evolutionary perspective (Berrigan and Charnov 1994). The main question to be resolved is: why do organisms grow fast and achieve smaller sizes under more favourable conditions (= relatively higher temperature), while they grow longer and achieve larger sizes under less favourable conditions (relatively lower temperature), if larger size means higher fitness, while longer development may be risky? This evolutionary conundrum still awaits an ultimate explanation (Angilletta Jr et al. 2004; Angilletta and Dunham 2003; Verberk et al. 2021). Although theoretical modelling has shown that such a growth pattern can be achieved as a response to temperature alone, with a specific combination of energetic parameters and external mortality (Kozłowski et al. 2004), it has been suggested that other temperature-dependent environmental variables may be the actual drivers of this pattern. One of the most frequently invoked variable is the relative oxygen availability in the environment (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2006; Audzijonyte et al. 2019; Verberk et al. 2021; Woods 1999), which decreases with temperature increase. Importantly, this effect is more pronounced in aquatic systems (Forster et al. 2012). However, other temperature-dependent parameters are also being examined in the context of their possible effect on TSR induction and strength. Food availability is among the interfering factors in this regard. In aquatic systems, nutritional conditions are generally better at higher temperature, while a range of relatively mild thermal conditions is considered. However, there are no conclusive results so far on how nutritional conditions affect the plastic body size response to acute temperature changes. A study by Bazin et al. (2023) examined this particular issue, the effects of food and temperature on TSR, in medaka fish. An important value of the study was to relate the patterns found to fitness. This is a rare and highly desirable approach since evolutionary significance of any results cannot be reliably interpreted unless shown as expressed in light of fitness. The authors compared the body size of fish kept at 20°C and 30°C under conditions of food abundance or food restriction. The results showed that the TSR (smaller body size at 30°C compared to 20°C) was observed in both food treatments, but the effect was delayed during fish development under food restriction. Regarding the relevance to fitness, increased temperature resulted in more eggs laid but higher mortality, while food restriction increased survival but decreased the number of eggs laid in both thermal treatments. Overall, food restriction seemed to have a more severe effect on development at 20°C than at 30°C, contrary to the authors’ expectations. I found this result particularly interesting. One possible interpretation, also suggested by the authors, is that the relative oxygen availability, which was not controlled for in this study, could have affected this pattern. According to theoretical predictions confirmed in quite many empirical studies so far, oxygen restriction is more severe at higher temperatures. Perhaps for these particular two thermal treatments and in the case of the particular species studied, this restriction was more severe for organismal performance than the food restriction. This result is an example that all three variables, temperature, food and oxygen, should be taken into account in future studies if the interrelationship between them is to be understood in the context of TSR. It also shows that the reasons for growing smaller in warm may be different from those for growing larger in cold, as suggested, directly or indirectly, in some previous studies (Hessen et al. 2010; Leiva et al. 2019). Since medaka fish represent predatory vertebrates, the results of the study contribute to the issue of global warming effect on food webs, as the authors rightly point out. This is an important issue because the general decrease in the size or organisms in the aquatic environment with global warming is a fact (e.g., Daufresne et al. 2009), while the question of how this might affect entire communities is not trivial to resolve (Ohlberger 2013). REFERENCES Angilletta Jr, M. J., T. D. Steury & M. W. Sears, 2004. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life–history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44:498-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498 Angilletta, M. J. & A. E. Dunham, 2003. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: Simple evolutionary explanations may not be general. American Naturalist 162(3):332-342. https://doi.org/10.1086/377187 Atkinson, D., 1994. Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms. Advances in Ecological Research 25:1-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3 Atkinson, D., S. A. Morley & R. N. Hughes, 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply? Evolution & Development 8(2):202-214 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x Audzijonyte, A., D. R. Barneche, A. R. Baudron, J. Belmaker, T. D. Clark, C. T. Marshall, J. R. Morrongiello & I. van Rijn, 2019. Is oxygen limitation in warming waters a valid mechanism to explain decreased body sizes in aquatic ectotherms? Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(2):64-77 https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12847 Bazin, S., Hemmer-Brepson, C., Logez, M., Sentis, A. & Daufresne, M. 2023. Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms. HAL, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3 Berrigan, D. & E. L. Charnov, 1994. Reaction norms for age and size at maturity in response to temperature – a puzzle for life historians. Oikos 70:474-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545787 Daufresne, M., K. Lengfellner & U. Sommer, 2009. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106(31):12788-93 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902080106 Forster, J., A. G. Hirst & D. Atkinson, 2012. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(47):19310-19314. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210460109 Hessen, D. O., P. D. Jeyasingh, M. Neiman & L. J. Weider, 2010. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004 Kozłowski, J., M. Czarnoleski & M. Dańko, 2004. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold? Integrative and Comparative Biology 44(6):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.480 Leiva, F. P., P. Calosi & W. C. E. P. Verberk, 2019. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374:20190035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0035 Ohlberger, J., 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body szie - from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12098 Verberk, W. C. E. P., D. Atkinson, K. N. Hoefnagel, A. G. Hirst, C. R. Horne & H. Siepel, 2021. Shrinking body sizes in response to warming: explanations for the temperature-size rule with special emphasis on the role of oxygen. Biological Reviews 96:247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12653 Woods, H. A., 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. American Zoologist 39:244-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.2.244 | Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms | Simon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne | <p>The reduction of body size with warming has been proposed as the third universal response to global warming, besides geographical and phenological shifts. Observed body size shifts in ectotherms are mostly attributed to the temperature size rul... |  | Climate change, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2022-07-27 09:28:29 | View | |

06 Jan 2021

Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech populationCathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio https://doi.org/10.1101/645747The complexity of predicting mortality in treesRecommended by Lucía DeSoto based on reviews by Lisa Hülsmann and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the main issues of forest ecosystems is rising tree mortality as a result of extreme weather events (Franklin et al., 1987). Eventually, tree mortality reduces forest biomass (Allen et al., 2010), although its effect on forest ecosystem fluxes seems not lasting too long (Anderegg et al., 2016). This controversy about the negative consequences of tree mortality is joined to the debate about the drivers triggering and the mechanisms accelerating tree decline. For instance, there is still room for discussion about carbon starvation or hydraulic failure determining the decay processes (Sevanto et al., 2014) or about the importance of mortality sources (Reichstein et al., 2013). Therefore, understanding and predicting tree mortality has become one of the challenges for forest ecologists in the last decade, doubling the rate of articles published on the topic (*). Although predicting the responses of ecosystems to environmental change based on the traits of species may seem a simplistic conception of ecosystem functioning (Sutherland et al., 2013), identifying those traits that are involved in the proneness of a tree to die would help to predict how forests will respond to climate threatens. (*) Number (and percentage) of articles found in Web of Sciences after searching (December the 10th, 2020) “tree mortality”: from 163 (0.006%) in 2010 to 412 (0.013%) in 2020. References Allen et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest ecology and management, 259(4), 660-684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001 | Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech population | Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio | <p>Since several studies have been reporting an increase in the decline of forests, a major issue in ecology is to better understand and predict tree mortality. The interactions between the different factors and the physiological processes giving ... |  | Climate change, Physiology, Population ecology | Lucía DeSoto | 2019-05-24 11:37:38 | View | |

01 Oct 2023

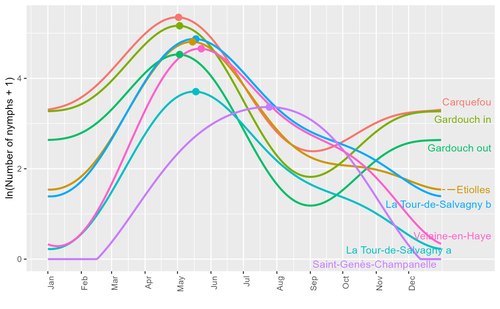

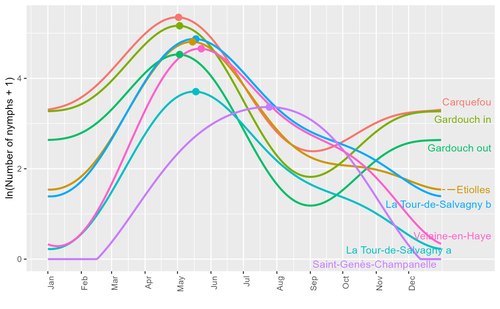

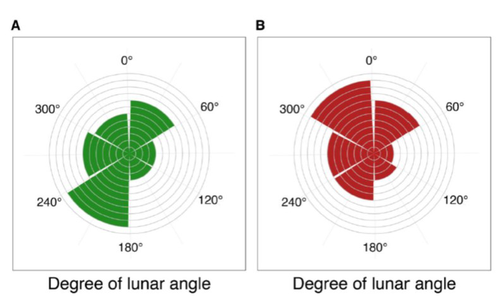

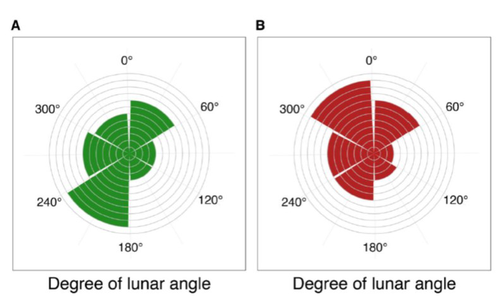

Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climateThierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Verheyden, Gwenaёl Vourc’h, Karine Chalvet-Monfray, Albert Agoulon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416Assessing seasonality of tick abundance in different climatic regionsRecommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne pathogens are considered as one of the major threats to public health – Lyme borreliosis being a well-known example of such disease. Global change – from climate change to changes in land use or invasive species – is playing a role in the increased risk associated with these pathogens. An important aspect of our knowledge of ticks and their associated pathogens is seasonality – one component being the phenology of within-year tick occurrences. This is important both in terms of health risk – e.g., when is the risk of encountering ticks high – and ecological understanding, as tick dynamics may depend on the weather as well as different hosts with their own dynamics and habitat use. Hoch et al. (2023) provide a detailed data set on the phenology of one species of tick, Ixodes ricinus, in 6 different locations of France. Whereas relatively cool sites showed a clear peak in spring-summer, warmer sites showed in addition relatively high occurrences in fall-winter, with a minimum in late summer-early fall. Such results add robust data to the existing evidence of the importance of local climatic patterns for explaining tick phenology. Recent analyses have shown that the phenology of Lyme borreliosis has been changing in northern Europe in the last 25 years, with seasonal peaks in cases occurring now 6 weeks earlier (Goren et al. 2023). The study by Hoch et al. (2023) is of too short duration to establish temporal changes in phenology (“only” 8 years, 2014-2021, see also Wongnak et al 2021 for some additional analyses; given the high year-to-year variability in weather, establishing phenological changes often require longer time series), and further work is needed to get better estimates of these changes and relate them to climate, land-use, and host density changes. Moreover, the phenology of ticks may also be related to species-specific tick phenology, and different tick species do not respond to current changes in identical ways (see for example differences between the two Ixodes species in Finland; Uusitalo et al. 2022). An efficient surveillance system requires therefore an adaptive monitoring design with regard to the tick species as well as the evolving causes of changes. References Goren, A., Viljugrein, H., Rivrud, I. M., Jore, S., Bakka, H., Vindenes, Y., & Mysterud, A. (2023). The emergence and shift in seasonality of Lyme borreliosis in Northern Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1993), 20222420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2420 Hoch, T., Madouasse, A., Jacquot, M., Wongnak, P., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Agoulon, A. (2023). Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climate. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416 Uusitalo, R., Siljander, M., Lindén, A., Sormunen, J. J., Aalto, J., Hendrickx, G., . . . Vapalahti, O. (2022). Predicting habitat suitability for Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Finland. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05410-8 Wongnak, P., Bord, S., Jacquot, M., Agoulon, A., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Chalvet-Monfray, K. (2022). Meteorological and climatic variables predict the phenology of Ixodes ricinus nymph activity in France, accounting for habitat heterogeneity. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11479-z | Seasonality of host-seeking *Ixodes ricinus* nymph abundance in relation to climate | Thierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Ve... | <p style="text-align: justify;">There is growing concern about climate change and its impact on human health. Specifically, global warming could increase the probability of emerging infectious diseases, notably because of changes in the geographic... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-10-14 18:43:56 | View | |

24 Jan 2023

Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic driversOmar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739Alpine ecology and their dynamics under climate changeRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewerResearch about the effects of climate change on ecological communities has been abundant in the last decades. In particular, studies about the effects of climate change on mountain ecosystems have been key for understanding and communicating the consequences of this global phenomenon. Alpine regions show higher increases in warming in comparison to low-altitude ecosystems and this trend is likely to continue. This warming has caused reduced snowfall and/or changes in the duration of snow cover. For example, Notarnicola (2020) reported that 78% of the world’s mountain areas have experienced a snow cover decline since 2000. In the same vein, snow cover has decreased by 10% compared with snow coverage in the late 1960s (Walther et al., 2002) and snow cover duration has decreased at a rate of 5 days/decade (Choi et al., 2010). These changes have impacted the dynamics of high-altitude plant and animal populations. Some impacts are changes in the hibernation of animals, the length of the growing season for plants and the soil microbial composition (Chávez et al. 2021). Lenzi et al. (2023), give us an excellent study using long-term data on alpine amphibian populations. Authors show how climate change has impacted the reproductive phenology of Bufo bufo, especially the breeding season starts 30 days earlier than ~40 years ago. This earlier breeding is associated with the increasing temperatures and reduced snow cover in these alpine ecosystems. However, these changes did not occur in a linear trend but a marked acceleration was observed until mid-1990s with a later stabilization. Authors associated these nonlinear changes with complex interactions between the global trend of seasonal temperatures and site-specific conditions. Beyond the earlier breeding season, changes in phenology can have important impacts on the long-term viability of alpine populations. Complex interactions could involve positive and negative effects like harder environmental conditions for propagules, faster development of juveniles, or changes in predation pressure. This study opens new research opportunities and questions like the urgent assessment of the global impact of climate change on animal fitness. This study provides key information for the conservation of these populations. References Chávez RO, Briceño VF, Lastra JA, Harris-Pascal D, Estay SA (2021) Snow Cover and Snow Persistence Changes in the Mocho-Choshuenco Volcano (Southern Chile) Derived From 35 Years of Landsat Satellite Images. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.643850 Choi G, Robinson DA, Kang S (2010) Changing Northern Hemisphere Snow Seasons. Journal of Climate, 23, 5305–5310. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3644.1 Lenzi O, Grossenbacher K, Zumbach S, Lüscher B, Althaus S, Schmocker D, Recher H, Thoma M, Ozgul A, Schmidt BR (2022) Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers.bioRxiv, 2022.08.16.503739, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739 Notarnicola C (2020) Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sensing of Environment, 243, 111781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111781 | Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers | Omar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt | <p style="text-align: justify;">Strong phenological shifts in response to changes in climatic conditions have been reported for many species, including amphibians, which are expected to breed earlier. Phenological shifts in breeding are observed i... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Zoology | Sergio Estay | Anonymous, Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-18 08:25:21 | View |

25 May 2021

Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assemblyCaio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho https://doi.org/10.1101/869966Environmental heterogeneity drives phytoplankton community assembly patterns in a tropical riverine systemRecommended by Cédric Hubas and Eric Goberville and Eric Goberville based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy

What predisposes two individuals to form and maintain a relationship is a fundamental question. Using facial recognition to see whether couples' faces change over time to become more and more similar, psychology researchers have concluded that couples tend to be formed from the start between people whose faces are more similar than average [1]. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. And what about in nature? Are these rules of assembly valid for communities of different species? In his seminal contribution, Robert MacArthur (1984) wrote ‘To do science is to search for repeated patterns’ [2]. Identifying the mechanisms that govern the arrangement of life is a hot research topic in the field of ecology for decades, and an absolutely essential prerequisite to answer the outstanding question of what shape ecological patterns in multi-species communities such as species-area relationships, relative species abundances, or spatial and temporal turnover of community composition; amid others [3]. To explain ecological patterns in nature, some rely on the concept that every species - through evolutionary processes and the acquisition of a unique set of traits that allow a species to be adapted to its abiotic and biotic environment - occupies a unique niche: Species coexistence comes as the result of niche differentiation [4,5]. Such a view has been challenged by the recognition of the key role of neutral processes [6], however, in which demographic stochasticity contributes to shape multi-species communities and to explain why congener species coexist much more frequently than expected by chance [7,8]. While the niche-based and neutral theories appear seemingly opposed at first sight [9], the dichotomy may be more philosophical than empirical [4,5]. Many examples have come to support that both concepts are not incompatible as they together influence the structure, diversity and functioning of communities [10], and are simply extreme cases of a continuum [11]. From this perspective, extrinsic factors, i.e., environmental heterogeneity, may influence the location of a given community along the niche-neutrality continuum. The walk of species in nature is therefore neither random nor ecologically predestined. In microbial assemblages, the co-existence of these two antagonistic mechanisms has been shown both theoretically and empirically. It has been shown that a combination of stabilising (niche) and equalising (neutral) mechanisms was responsible for the existence of groups of coexistent species (clumps) in a phytoplankton rich community [12]. Analysing interannual changes (2003-2009) in the weekly abundance of diatoms and dinoflagellates located in a temperate coastal ecosystem of the Western English Channel, Mutshinda et al. [13] found a mixture of biomass dynamics consistent with the neutrality-niche continuum hypothesis. While niche processes explained the dynamic of phytoplankton functional groups (i.e., diatoms vs. dinoflagellates) in terms of biomass, neutral processes mainly dominated - 50 to 75% of the time - the dynamics at the species level within functional groups [13]. From one endpoint to another, defining the location of a community along the continuum is all matter of scale [4,11]. In their study, testing predictions made by an emergent neutrality model, Graco-Roza et al. [14] provide empirical evidence that neutral and niche processes joined together to shape and drive planktonic communities in a riverine ecosystem. Body size - the 'master trait' - is used here as a discriminant ecological dimension along the niche axis. From their analysis, they not only show that the specific abundance is organised in clumps and gaps along the niche axis, but also reveal that different clumps exist along the river course. They identify two main clumps in body size - with species belonging to three different morphologically-based functional groups - and characterise that among-species differences in biovolume are driven by functional redundancy at the clump level; species functional distinctiveness being related to the relative biovolume of species. By grouping their variables according to seasons (cold-dry vs. warm-wet) or river elevation profile (upper, medium and lower course), they hereby highlight how environmental heterogeneity contributes to shape species assemblages and their dynamics and conclude that emergent neutrality models are a powerful approach to explain species coexistence; and therefore ecological patterns. References [1] Tea-makorn PP, Kosinski M (2020) Spouses’ faces are similar but do not become more similar with time. Scientific Reports, 10, 17001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73971-8. [2] MacArthur RH (1984) Geographical Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Species. Princeton University Press. [3] Vellend M (2020) The Theory of Ecological Communities (MPB-57). Princeton University Press. [4] Wennekes PL, Rosindell J, Etienne RS (2012) The Neutral—Niche Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. Acta Biotheoretica, 60, 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10441-012-9144-6. [5] Gravel D, Guichard F, Hochberg ME (2011) Species coexistence in a variable world. Ecology Letters, 14, 828–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01643.x. [6] Hubbell SP (2001) The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography (MPB-32). Princeton University Press. [7] Leibold MA, McPeek MA (2006) Coexistence of the Niche and Neutral Perspectives in Community Ecology. Ecology, 87, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1399:COTNAN]2.0.CO;2. [8] Pielou EC (1977) The Latitudinal Spans of Seaweed Species and Their Patterns of Overlap. Journal of Biogeography, 4, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038189. [9] Holt RD (2006) Emergent neutrality. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21, 531–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.003. [10] Scheffer M, Nes EH van (2006) Self-organized similarity, the evolutionary emergence of groups of similar species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 6230–6235. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508024103. [11] Gravel D, Canham CD, Beaudet M, Messier C (2006) Reconciling niche and neutrality: the continuum hypothesis. Ecology Letters, 9, 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00884.x. [12] Vergnon R, Dulvy NK, Freckleton RP (2009) Niches versus neutrality: uncovering the drivers of diversity in a species-rich community. Ecology Letters, 12, 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01364.x. [13] Mutshinda CM, Finkel ZV, Widdicombe CE, Irwin AJ (2016) Ecological equivalence of species within phytoplankton functional groups. Functional Ecology, 30, 1714–1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12641. [14] Graco-Roza C, Segura AM, Kruk C, Domingos P, Soininen J, Marinho MM (2021) Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly. bioRxiv, 869966, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/869966

| Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly | Caio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho | <p style="text-align: justify;">Emergent neutrality (EN) suggests that species must be sufficiently similar or sufficiently different in their niches to avoid interspecific competition. Such a scenario results in a transient pattern with clumps an... |  | Coexistence, Community ecology, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Hubas | 2020-01-23 16:11:32 | View | |

20 Oct 2021

Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population declineAvril Weinbach, Nicolas Loeuille, Rudolf P. Rohr https://doi.org/10.1101/570580Doomed by your partner: when mutualistic interactions are like an evolutionary millstone around a species’ neckRecommended by Sylvain Billiard based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Mutualistic interactions are the weird uncles of population and community ecology. They are everywhere, from the microbes aiding digestion in animals’ guts to animal-pollination services in ecosystems; They increase productivity through facilitation; They fascinate us when small birds pick the teeth of a big-mouthed crocodile. Yet, mutualistic interactions are far less studied and understood than competition or predation. Possibly because we are naively convinced that there is no mystery here: isn’t it obvious that mutualistic interactions necessarily facilitate species coexistence? Since mutualistic species benefit from one another, if one species evolves, the other should just follow, isn’t that so? It is not as simple as that, for several reasons. First, because simple mutualistic Lotka-Volterra models showed that most of the time mutualistic systems should drift to infinity and be unstable (e.g. Goh 1979). This is not what happens in natural populations, so something is missing in simple models. At a larger scale, that of communities, this is even worse, since we are still far from understanding the link between the topology of mutualistic networks and the stability of a community. Second, interactions are context-dependent: mutualistic species exchange resources, and thus from the point of view of one species the interaction is either beneficial or not, depending on the net gain of energy (e.g. Holland and DeAngelis 2010). In other words, considering interactions as mutualistic per se is too caricatural. Third, since evolution is blind, the evolutionary response of a species to an environmental change can have any effect on its mutualistic partner, and not necessarily a neutral or positive effect. This latter reason is particularly highlighted by the paper by A. Weinbach et al. (2021). Weinbach et al. considered a simple two-species mutualistic Lotka-Volterra model and analyzed the evolutionary dynamics of a trait controlling for the rate of interaction between the two species by using the classical Adaptive Dynamics framework. They showed that, depending on the form of the trade-off between this interaction trait and its effect on the intrinsic growth rate, several situations can occur at evolutionary equilibrium: species can stably coexist and maintain their interaction, or the interaction traits can evolve to zero where species can coexist without any interactions. Weinbach et al. then investigated the fate of the two-species system if a partner species is strongly affected by environmental change, for instance, a large decrease of its growth rate. Because of the supposed trade-off between the interaction trait and the growth rate, the interaction trait in the focal species tends to decrease as an evolutionary response to the decline of the partner species. If environmental change is too large, the interaction trait can evolve to zero and can lead the partner species to extinction. An “evolutionary murder”. Even though Weinbach et al. interpreted the results of their model through the lens of plant-pollinators systems, their model is not specific to this case. On the contrary, it is very general, which has advantages and caveats. By its generality, the model is informative because it is a proof of concept that the evolution of mutualistic interactions can have unexpected effects on any category of mutualistic systems. Yet, since the model lacks many specificities of plant-pollinator interactions, it is hard to evaluate how their result would apply to plant-pollinators communities. I wanted to recommend this paper as a reminder that it is certainly worth studying the evolution of mutualistic interactions, because i) some unexpected phenomenons can occur, ii) we are certainly too naive about the evolution and ecology of mutualistic interactions, and iii) one can wonder to what extent we will be able to explain the stability of mutualistic communities without accounting for the co-evolutionary dynamics of mutualistic species. References Goh BS (1979) Stability in Models of Mutualism. The American Naturalist, 113, 261–275. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2460204. Holland JN, DeAngelis DL (2010) A consumer–resource approach to the density-dependent population dynamics of mutualism. Ecology, 91, 1286–1295. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1163.1 Weinbach A, Loeuille N, Rohr RP (2021) Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population decline. bioRxiv, 570580, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/570580 | Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population decline | Avril Weinbach, Nicolas Loeuille, Rudolf P. Rohr | <p style="text-align: justify;">With current environmental changes, evolution can rescue declining populations, but what happens to their interacting species? Mutualistic interactions can help species sustain each other when their environment wors... |  | Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Interaction networks, Pollination, Theoretical ecology | Sylvain Billiard | 2019-09-05 11:29:45 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle