Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Nov 2020

Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functionsAllan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.10.144337Hidden diversity: how genetic richness affects species diversity and ecosystem processes in freshwater pondsRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Andrew Barnes and Jes HinesBiodiversity loss can have important consequences for ecosystem functions, as exemplified by a large body of literature spanning at least three decades [1–3]. While connections between species diversity and ecosystem functions are now well-defined and understood, the importance of diversity within species is more elusive. Despite a surge in theoretical work on how intraspecific diversity can affect coexistence in simple community types [4,5], not much is known about how intraspecific diversity drives ecosystem processes in more complex community types. One particular challenge is that intraspecific diversity can be expressed as observable variation of functional traits, or instead subsist as genetic variation of which the consequences for ecosystem processes are harder to grasp. References [1] Tilman D, Downing JA (1994) Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature, 367, 363–365. https://doi.org/10.1038/367363a0 | Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functions | Allan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. | <p>Loss in intraspecific diversity can alter ecosystem functions, but the underlying mechanisms are still elusive, and intraspecific biodiversity-ecosystem function relationships (iBEF) have been restrained to primary producers. Here, we manipulat... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Freshwater ecology | Frederik De Laender | Andrew Barnes | 2020-06-15 09:04:53 | View |

18 Mar 2019

Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasiteAmalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2592114Limited dispersal in a vector on territorial hostsRecommended by Adele Mennerat based on reviews by Shelly Lachish and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitism requires parasites and hosts to meet and is therefore conditioned by their respective dispersal abilities. While dispersal has been studied in a number of wild vertebrates (including in relation to infection risk), we still have poor knowledge of the movements of their parasites. Yet we know that many parasites, and in particular vectors transmitting pathogens from host to host, possess the ability to move actively during at least part of their lives. References | Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasite | Amalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy | <p>Functional dispersal (between-site movement, with or without subsequent reproduction) is a key trait acting on the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of a species, with potential cascading effects on other members of the local community. ... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Epidemiology, Parasitology, Population ecology | Adele Mennerat | 2018-11-05 11:44:58 | View | |

28 Feb 2023

Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird communityAmbre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715Two common European songbirds elicit different community responses with their mobbing callsRecommended by Tim Parker based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many bird species participate in mobbing in which individuals approach a predator while producing conspicuous vocalizations (Magrath et al. 2014). Mobbing is interesting to behavioral ecologists because of the complex array of costs of benefits. Costs range from the obvious risk of approaching a predator while drawing that predator’s attention to the more mundane opportunity costs of taking time away from other activities, such as foraging. Benefits may involve driving the predator to leave, teaching relatives to recognize predators, signaling quality to conspecifics, or others. An added layer of complexity in this system comes from the inter-specific interactions that often occur among different mobbing species (Magrath et al. 2014). This study by Salis et al. (2023) explored the responses of a local bird community to mobbing calls produced by individuals of two common mobbing species in European forests, coal tits, and crested tits. Not only did they compare responses to these two different species, they assessed the impact of the number of mobbing individuals on the stimulus recordings, and they did so at two very different times of the year with different social contexts for the birds involved, winter (non-breeding) and spring (breeding). The experiment was well-designed and highly powered, and the authors tested and confirmed an important assumption of their design, and thus the results are convincing. It is clear that members of the local bird community responded differently to the two different species, and this result raises interesting questions about why these species differed in their tendency to attract additional mobbers. For instance, are species that recruit more co-mobbers more effective at recruiting because they are more reliable in their mobbing behavior (Magrath et al. 2014), more likely to reciprocate (Krams and Krama, 2002), or for some other reason? Hopefully this system, now of proven utility thanks to the current study, will be useful for following up on hypotheses such as these. Other convincing results, such as the higher rate of mobbing response in winter than in spring, also merit following up with further work. Finally, their observation that playback of vocalizations of multiple individuals often elicited a more mobbing response that the playback of vocalizations of a single individual are interesting and consistent with other recent work indicating that groups of mobbers recruit more additional mobbers than do single mobbers (Dutour et al. 2021). However, as acknowledged in the manuscript, the design of the current study did not allow a distinction between the effect of multiple individuals signaling versus an effect of a stronger stimulus. Thus, this last result leaves the question of the effect of mobbing group size in these species open to further study. REFERENCES Dutour M, Kalb N, Salis A, Randler C (2021) Number of callers may affect the response to conspecific mobbing calls in great tits (Parus major). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 75, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-02969-7 Krams I, Krama T (2002) Interspecific reciprocity explains mobbing behaviour of the breeding chaffinches, Fringilla coelebs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 269, 2345–2350. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2155 Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN (2015) Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biological Reviews, 90, 560–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12122 Salis A, Lena JP, Lengagne T (2023) Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490715, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715 | Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community | Ambre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne | <p>Heterospecific communication is common for birds when mobbing a predator. However, joining the mob should depend on the number of callers already enrolled, as larger mobs imply lower individual risks for the newcomer. In addition, some ‘communi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Community ecology, Social structure | Tim Parker | 2022-05-06 09:29:30 | View | ||

11 Mar 2024

Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammalAmin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920Stress and stress hormones’ transmission from mothers to offspringRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Individuals can respond to environmental changes that they undergo directly (within-generation plasticity) but also through transgenerational plasticity, providing lasting effects that are transmitted to the next generations (Donelson et al. 2012; Munday et al. 2013; Kuijper & Hoyle 2015; Auge et al. 2017, Tariel et al. 2020). These parental effects can affect offspring via various mechanisms, notably via maternal transmission of hormones to the eggs or growing embryos (Mousseau & Fox 1998). While the effects of environmental quality may simply carry-over to the next generation (e.g., females in stressful environments give birth to offspring in poorer condition), parental effects may also be a mechanism that adjusts offspring phenotype in response to environmental variation and predictability, and thereby match offspring's phenotype to future environmental conditions (Gluckman et al. 2005; Marshall & Uller 2007; Dey et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2019), for example by preparing their offspring to an expected stressful environment. When females experience stress during gestation or egg formation, elevations in glucocorticoids (GC) are expected to affect offspring phenotype in many ways, from the offspring's own GC levels, to their growth and survival (Sheriff et al. 2017). This is a well established idea, but how strong is the evidence for this? A meta-analysis on birds found no clear effect of corticosterone manipulation on offspring traits (38 studies on 9 bird species for corticosterone manipulation; Podmokła et al. 2018). Another meta-analysis including 14 vertebrate species found no clear effect of prenatal stress on offspring GC (Thayer et al. 2018). Finally, a meta-analysis on wild vertebrates (23 species) found no clear effect of GC-mediated maternal effects on offspring traits (MacLeod et al. 2021). As often when facing such inconclusive results, context dependence has been suggested as one potential reason for such inconsistencies, for exemple sex specific effects (Groothuis et al. 2019, 2020). However, sex specific measures on offspring are scarce (Podmokła et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature available is still limited to a few, mostly “model” species. With their study, Amin et al. (2024) show the way to improve our understanding on GC transmission from mother to offspring and its effects in several aspects. First they used innovative non-invasive methods (which could broaden the range of species available to study) by quantifying cortisol metabolites from faecal samples collected from pregnant females, as proxy for maternal GC level, and relating it to GC levels from hairs of their neonate offspring. Second they used a free ranging large mammal (taxa from which literature is missing): the fallow deer (Dama dama). Third, they provide sex specific measures of GC levels. And finally but importantly, they are exemplary in their transparency regarding 1) the exploratory nature of their study, 2) their statistical thinking and procedure, and 3) the study limitations (e.g., low sample size and high within individual variation of measurements). I hope this study will motivate more research (on the fallow deer, and on other species) to broaden and strengthen our understanding of sex specific effects of maternal stress and CG levels on offspring phenotype and fitness. References Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., & Ciuti, S. (2024). Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and foetal glucocorticoids in a free-ranging large mammal. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920 Auge, G.A., Leverett, L.D., Edwards, B.R. & Donohue, K. (2017). Adjusting phenotypes via within-and across-generational plasticity. New Phytologist, 216, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14495 Dey, S., Proulx, S.R. & Teotonio, H. (2016). Adaptation to temporally fluctuating environments by the evolution of maternal effects. PLoS biology, 14, e1002388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002388 Donelson, J.M., Munday, P.L., McCormick, M.I. & Pitcher, C.R. (2012). Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1323 Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A. & Spencer, H.G. (2005). Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001 Groothuis, Ton GG, Bin-Yan Hsu, Neeraj Kumar, and Barbara Tschirren. "Revisiting mechanisms and functions of prenatal hormone-mediated maternal effects using avian species as a model." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374, no. 1770 (2019): 20180115. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0115 Groothuis, Ton GG, Neeraj Kumar, and Bin-Yan Hsu. "Explaining discrepancies in the study of maternal effects: the role of context and embryo." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36 (2020): 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.10.006 Kuijper, B. & Hoyle, R.B. (2015). When to rely on maternal effects and when on phenotypic plasticity? Evolution, 69, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12635 MacLeod, Kirsty J., Geoffrey M. While, and Tobias Uller. "Viviparous mothers impose stronger glucocorticoid‐mediated maternal stress effects on their offspring than oviparous mothers." Ecology and Evolution 11, no. 23 (2021): 17238-17259. Marshall, D.J. & Uller, T. (2007). When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos, 116, 1957–1963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x Mousseau, T.A. & Fox, C.W. (1998). Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press. Munday, P.L., Warner, R.R., Monro, K., Pandolfi, J.M. & Marshall, D.J. (2013). Predicting evolutionary responses to climate change in the sea. Ecology Letters, 16, 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12185 Podmokła, Edyta, Szymon M. Drobniak, and Joanna Rutkowska. "Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method–a meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 93, no. 3 (2018): 1499-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12406 Sheriff, M. J., Bell, A., Boonstra, R., Dantzer, B., Lavergne, S. G., McGhee, K. E., MacLeod, K. J., Winandy, L., Zimmer, C., & Love, O. P. (2017). Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105 Tariel, Juliette, Sandrine Plénet, and Émilien Luquet. "Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (2020): 548660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.548660 Thayer, Zaneta M., Meredith A. Wilson, Andrew W. Kim, and Adrian V. Jaeggi. "Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: A phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species." Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 4942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23169-w Yin, J., Zhou, M., Lin, Z., Li, Q.Q. & Zhang, Y.-Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects benefit offspring across diverse environments: a meta-analysis in plants and animals. Ecology letters, 22, 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13373 | Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammal | Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Maternal phenotypes can have long-term effects on offspring phenotypes. These maternal effects may begin during gestation, when maternal glucocorticoid (GC) levels may affect foetal GC levels, thereby having an orga... | Evolutionary ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Physiology, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-06-05 09:06:56 | View | ||

10 Jan 2019

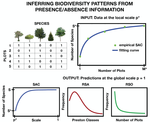

Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrencesAnna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan https://doi.org/10.1101/387456Upscaling the neighborhood: how to get species diversity, abundance and range distributions from local presence/absence dataRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer

How do you estimate the biodiversity of a whole community, or the distribution of abundances and ranges of its species, from presence/absence data in scattered samples? ADDITIONAL COMMENTS 1) To explain the novelty of the authors' contribution, it is useful to look at competing techniques. 2) The main condition for all such approaches to work is well-mixedness: each sample should be sufficiently like a lot drawn from the same skewed lottery. As long as that condition applies, finding the best approach is a theoretical matter of probabilities and combinatorics that may, in time, be given a definite answer. 3) One may ask: why the Negative Binomial as a Species Abundance Distribution? References [1] Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S., & Williams, C. B. (1943). The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 42-58. doi: 10.2307/1411 | Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences | Anna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan | <p>Biodiversity provides support for life, vital provisions, regulating services and has positive cultural impacts. It is therefore important to have accurate methods to measure biodiversity, in order to safeguard it when we discover it to be thre... |  | Macroecology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2018-08-09 16:44:09 | View | |

07 Oct 2019

Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities?Antoine Gardarin and Muriel Valantin-Morison https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3468920On the importance of experimental design: pitfall traps and arthropod communitiesRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cécile ALBERT and Matthias Foellmer based on reviews by Cécile ALBERT and Matthias Foellmer

Despite the increasing refinement of statistical methods, a robust experimental design is still one of the most important cornerstones to answer ecological and evolutionary questions. However, there is a strong trade-off between a perfect design and its feasibility. A common mantra is that more data is always better, but how much is enough is complex to answer, specially when we want to capture the spatial and temporal variability of a given process. Gardarin and Valantin-Morison [1] make an effort to answer these questions for a practical case: How many pitfalls traps, of which type, and over which extent, do we need to detect shifts in arthropod community composition in agricultural landscapes. There is extense literature on how to approach these challenges using preliminary data in combination with simulation methods [e.g. 2], but practical cases are always welcomed to illustrate the complexity of the decisions to be made. A key challenge in this situation is the nature of simplified and patchy agricultural arthropod communities. In this context, small effect sizes are expected, but those small effects are relevant from an ecological point of view because small increases at low biodiversity may produce large gains in ecosystem functioning [3]. References [1] Gardarin, A. and Valantin-Morison, M. (2019). Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities? Zenodo, 3468920, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3468920 | Which pitfall traps and sampling efforts should be used to evaluate the effects of cropping systems on the taxonomic and functional composition of arthropod communities? | Antoine Gardarin and Muriel Valantin-Morison | <p>1. Ground dwelling arthropods are affected by agricultural practices, and analyses of their responses to different crop management are required. The sampling efficiency of pitfall traps has been widely studied in natural ecosystems. In arable a... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Biological control, Community ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2019-01-08 09:40:14 | View | |

29 Jan 2020

Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stabilityArnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya https://doi.org/10.1101/589895On the importance of stoichiometric constraints for understanding global change effects on food web dynamicsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe constraints associated with the mass balance of chemical elements (i.e. stoichiometric constraints) are critical to our understanding of ecological interactions, as outlined by the ecological stoichiometry theory [1]. Species in ecosystems differ in their elemental composition as well as in their level of elemental homeostasis [2], which can determine the outcome of interactions such as herbivory or decomposition on species coexistence and ecosystem functioning [3, 4]. References [1] Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J. (2017). Ecological Stoichiometry, The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. doi: 10.1515/9781400885695 | Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability | Arnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya | <p>Temperature and nutrients are two of the most important drivers of global change. Both can modify the elemental composition (i.e. stoichiometry) of primary producers and consumers. Yet their combined effect on the stoichiometry, dynamics, and s... |  | Climate change, Community ecology, Food webs, Theoretical ecology, Thermal ecology | Elisa Thebault | 2019-08-08 12:20:08 | View | |

23 Mar 2020

Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascadesArnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne https://doi.org/10.1101/722140Tell me what you’ve eaten, I’ll tell you how much you’ll eat (and be eaten)Recommended by Sara Magalhães and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 1 anonymous reviewerTritrophic interactions have a central role in ecological theory and applications [1-3]. Particularly, systems comprised of plants, herbivores and predators have historically received wide attention given their ubiquity and economic importance [4]. Although ecologists have long aimed to understand the forces that govern alternating ecological effects at successive trophic levels [5], several key open questions remain (at least partially) unanswered [6]. In particular, the analysis of complex food webs has questioned whether ecosystems can be viewed as a series of trophic chains [7,8]. Moreover, whether systems are mostly controlled by top-down (trophic cascades) or bottom-up processes remains an open question [6]. References [1] Price, P. W., Bouton, C. E., Gross, P., McPheron, B. A., Thompson, J. N., & Weis, A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 11(1), 41-65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353 | Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades | Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne | <p>Trophic cascades, the indirect effect of predators on non-adjacent lower trophic levels, are important drivers of the structure and dynamics of ecological communities. However, the influence of intraspecific trait variation on the strength of t... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Food webs, Population ecology | Sara Magalhães | 2019-08-02 09:11:03 | View | |

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

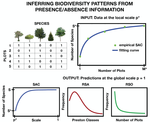

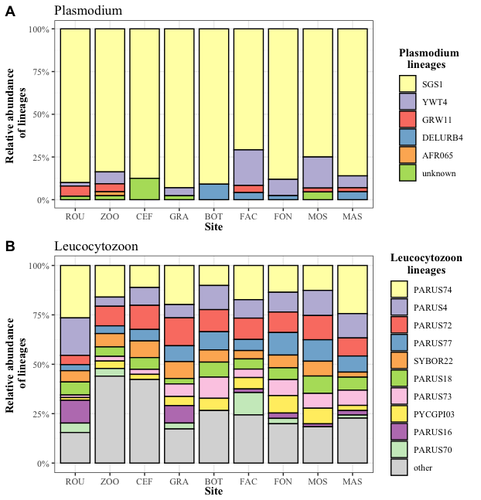

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle