Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Aug 2021

A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm callSamantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5Does the active vocabulary in Great-tailed Grackles supports their range expansion? New study will find outRecommended by Jan Oliver Engler based on reviews by Guillermo Fandos and 2 anonymous reviewersAlarm calls are an important acoustic signal that can decide the life or death of an individual. Many birds are able to vary their alarm calls to provide more accurate information on e.g. urgency or even the type of a threatening predator. According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis, the habitat plays an important role too in how acoustic patterns get transmitted. This is of particular interest for range-expanding species that will face new environmental conditions along the leading edge. One could hypothesize that the alarm call repertoire of a species could increase in newly founded ranges to incorporate new habitats and threats individuals might face. Hence selection for a larger active vocabulary might be beneficial for new colonizers. Using the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a model species, Samantha Bowser from Arizona State University and Maggie MacPherson from Louisiana State University want to find out exactly that. The Great-Tailed Grackle is an appropriate species given its high vocal diversity. Also, the species consists of different subspecies that show range expansions along the northern range edge yet to a varying degree. Using vocal experiments and field recordings the researchers have a high potential to understand more about the acoustic adaptation hypothesis within a range dynamic process. Over the course of this assessment, the authors incorporated the comments made by two reviewers into a strong revision of their research plans. With that being said, the few additional comments made by one of the initial reviewers round up the current stage this interesting research project is in. To this end, I can only fully recommend the revised research plan and am much looking forward to the outcomes from the author’s experiments, modeling, and field data. With the suggestions being made at such an early stage I firmly believe that the final outcome will be highly interesting not only to an ornithological readership but to every ecologist and biogeographer interested in drivers of range dynamic processes. References Bowser, S., MacPherson, M. (2021). A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call. In principle recommendation by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5. Version 3 | A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call | Samantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson | <p>The acoustic adaptation hypothesis posits that animal sounds are influenced by the habitat properties that shape acoustic constraints (Ey and Fischer 2009, Morton 2015, Sueur and Farina 2015).Alarm calls are expected to signal important habitat... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Coexistence, Dispersal & Migration, Habitat selection, Landscape ecology | Jan Oliver Engler | Darius Stiels, Anonymous | 2020-12-01 18:11:02 | View |

22 Nov 2021

When more competitors means less harvested resourceRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Francois Massol, Jeremy Van Cleve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois Massol, Jeremy Van Cleve and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper, Alan R. Rogers (2021) examines the dynamics of foraging strategies for a resource that gains value over time (e.g., ripening fruits), while there is a fixed cost of attempting to forage the resource, and once the resource is harvested nothing is left for other harvesters. For this model, not any pure foraging strategy is evolutionary stable. A mixed equilibrium exists, i.e., with a mixture of foraging strategies within the population, which is still evolutionarily unstable. Nonetheless, Alan R. Rogers shows that for a large number of competitors and/or high harvesting cost, the mixture of strategies remains close to the mixed equilibrium when simulating the dynamics. Surprisingly, in a large population individuals will less often attempt to forage the resource and will instead “go fishing”. The paper also exposes an experiment of the game with students, which resulted in a strategy distribution somehow close to the theoretical mixture of strategies. The economist John F. Nash Jr. (1950) gained the Nobel Prize of economy in 1994 for his game theoretical contributions. He gave his name to the “Nash equilibrium”, which represents a set of individual strategies that is reached whenever all the players have nothing to gain by changing their strategy while the strategies of others are unchanged. Alan R. Rogers shows that the mixed equilibrium in the foraging game is such a Nash equilibrium. Yet it is evolutionarily unstable insofar as a distribution close to the equilibrium can invade. The insights of the study are twofold. First, it sheds light on the significance of Nash equilibrium in an ecological context of foraging strategies. Second, it shows that an evolutionarily unstable state can rule the composition of the ecological system. Therefore, the contribution made by the paper should be most significant to better understand the dynamics of competitive communities and their eco-evolutionary trajectories. References Nash JF (1950) Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 36, 48–49. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.36.1.48 Rogers AR (2021) Beating your Neighbor to the Berry Patch. bioRxiv, 2020.11.12.380311, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.12.380311

| Beating your neighbor to the berry patch | Alan R. Rogers | <p style="text-align: justify;">Foragers often compete for resources that ripen (or otherwise improve) gradually. What strategy is optimal in this situation? It turns out that there is no optimal strategy. There is no evolutionarily stable strateg... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Foraging | François Munoz | Erol Akçay, Jorge Peña, Sébastien Lion, François Rousset, Ulf Dieckmann , Troy Day , Corina Tarnita , Florence Debarre , Daniel Friedman , Vlastimil Krivan , Ulf Dieckmann | 2020-12-10 18:38:49 | View |

15 May 2023

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new contextLogan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xsAn experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativenessRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer

Whether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014). Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027 Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019) Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs | Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context | Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. Howev... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-01-13 19:08:52 | View | ||

07 Aug 2023

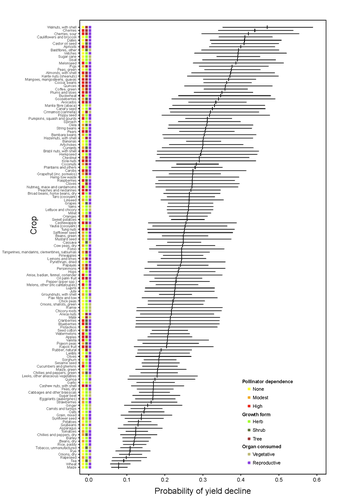

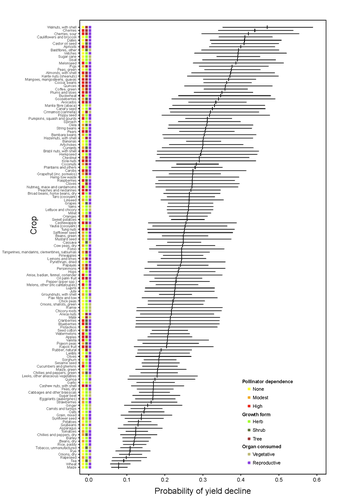

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

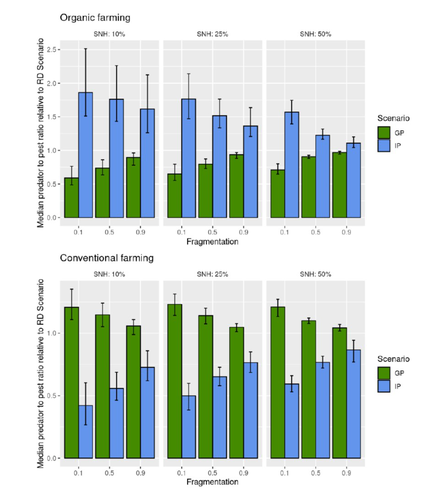

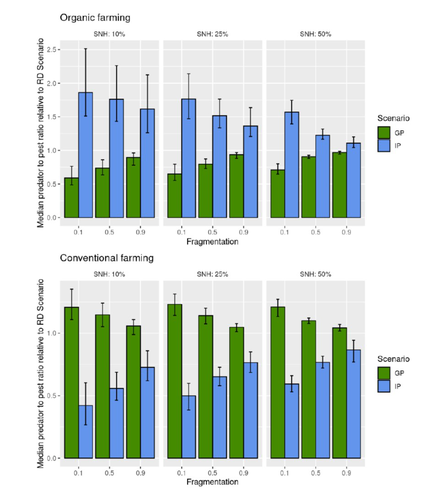

20 Feb 2023

Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approachThomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006Towards model-guided organic farming expansion for crop pest managementRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart

Reduce the impact the intensification of human activities has on the environmental is the challenge the humanity faces today, a major challenge that could be compared to climbing Everest without an oxygen supply. Indeed, over-population, pollution, burning fossil fuels, and deforestation are all evils which have had hugely detrimental effects on the environment such as climate change, soil erosion, poor air quality, and scarcity of drinking water to name but a few. In response to the ever-growing consumer demand, agriculture has intensified massively along with a drastic increase in the use of chemicals to ensure an adequate food supply while controlling crop pests. In this context, to address the disastrous effects of the intensive usage of pesticides on both human health and biodiversity, organic farming (OF) revealed as a miracle remedy with multiple benefits. Delattre et al. (2023) present a powerful modelling approach to decipher the crossed effects of the landscape structure and the OF expansion scenario on the pest abundance, both in organic and conventional (CF) crop fields. To this end, the authors ingeniously combined a grid-based landscape model with a spatially explicit predator-pest model. Based on an extensive in silico simulation process, they explore a diversity of landscape structures differing in their amount of semi-natural habitats (SHN) and in their fragmentation, to finally propose a ranking of various expansion scenarios according to the pest control methods in organic farming as well as to the pest and predators’ dissemination capacities. In total, 9 landscape structures (3 proportions of SHN x 3 fragmentation levels) were crossed with 3 expansion scenarios (RD = a random distribution of OF and CF in the grid; IP = isolated CF are converted; GP = CF within aggregates are converted), 4 pest management practices, 3 initial densities and 36 biological parameter combinations driving the predator’ and pest’s population dynamics. This exhaustive exploration of possible combinations of landscape and farming practices highlighted the main drivers of the various OF expansion scenarios, such as increased spillover of predators in isolated OF/CF fields, increased pest management efficiency in large patches of CF and the importance of the distance between OF and CF. In the end, this study brings to light the crucial role that landscape planning plays when OF practices have limited efficiency on pests. It also provides convincing arguments to the fact that converting to organic isolated CF as a priority seems to be the most promising scenario to limit pest densities in CF crops while improving predator to pest ratios (considered as a proxy of conservation biological control) in OF ones without increasing pest densities. Once further completed with model calibration validation based on observed life history traits data for both predators and pests, this work should be very helpful in sustaining policy makers to convince farmers of engaging in organic farming. REFERENCES Delattre T, Memah M-M, Franck P, Valsesia P, Lavigne C (2023) Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach. bioRxiv, 2022.05.31.494006, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006 | Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach | Thomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organic Farming (OF) has been expanding recently around the world in response to growing consumer demand and as a response to environmental concerns. Its share of agricultural landscapes is expected to increase in t... |  | Agroecology, Biological control, Landscape ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-06-03 11:41:14 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

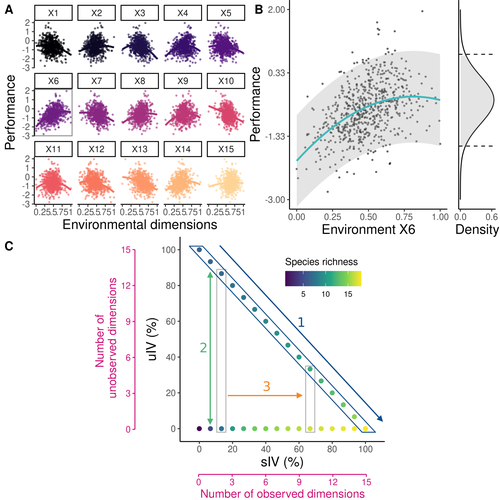

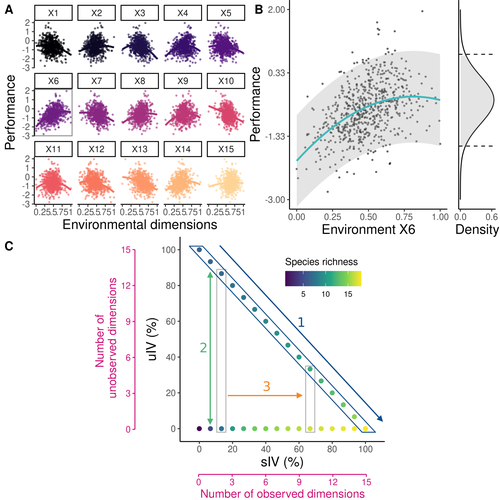

Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structureCamille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032Two paradigms for intraspecific variabilityRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman

Community ecology usually concerns itself with understanding the causes and consequences of diversity at a given taxonomic resolution, most classically at the species level. Yet there is no doubt that diversity exists at all scales, and phenotypic variability within a taxon can be comparable to differences between taxa, as observed from bacteria to fish and trees. The question that motivates an active and growing body of work (e.g. Raffard et al 2019) is not so much whether intraspecific variability matters, but what we get wrong by ignoring it and how to incorporate it into our understanding of communities. There is no established way to think about diversity at multiple nested taxonomic levels, and it is tempting to summarize intraspecific variability simply by measuring species mean and variance in any trait and metric. In this study, Girard-Tercieux et al (2023a) propose that, to understand its impact on community-level outcomes and in particular on species coexistence, we should carefully distinguish between two ways of thinking about intraspecific variability: -"unstructured" variation, where every individual's features are like an independent random draw from a species-specific distribution, for instance, due to genetic lottery and developmental accidents -"structured" variation that is due to each individual encountering a different but enduring microenvironment. The latter type of variability may still appear complex and random-like when the environment is high-dimensional (i.e. multifaceted, with many different factors contributing to each individual's performance and development). Thus, it is not necessarily "structured" in the sense of being easily understood -- we may need to measure more aspects of the environment than is practical if we want to fully predict these variations. What distinguishes this "structured" variability is that it is, in a loose sense, inheritable: individuals from the same species that grow in the same microenvironment will have the same performance, in a repeatable fashion. Thus, if each species is best at exploiting at least a fraction of environmental conditions, it is likely to avoid extinction by competition, except in the unlucky case of no propagule reaching any of the favorable sites. The core intuition, that the complex spatial structure and high-dimensional nature of the environment plays a key explanatory role in species coexistence, is a running thread through several of the authors' work (e.g. Clark et al 2010), clearly inspired by their focus on tropical forests. This study, by tackling the question of intraspecific determinants of interspecific outcomes, makes a compelling addition to this line of investigation, coming as a theoretical companion to a more data-oriented study (Girard-Tercieux et al 2023b). But I believe it raises a question that is even broader in scope. This kind of intraspecific variability, due to different individuals growing in different microenvironments, is perhaps most relevant for trees and other sessile organisms, but the distinction made here between "unstructured" and "structured" variability can likely be extended to many other ecological settings. In my understanding, what matters most in "structured" variability is not so much it stemming from a fixed environment, but rather it being maintained across generations, rather than possibly lost by drift. This difference between variability in the form of "frozen" randomness and in the form of stochastic drift over time is highly relevant in other theoretical fields (e.g. in physics, where it is the difference between a disordered solid and a liquid), and thus, I expect that it is a meaningful distinction to make throughout community ecology. References James S. Clark, David Bell, Chengjin Chu, Benoit Courbaud, Michael Dietze, Michelle Hersh, Janneke HilleRisLambers et al. (2010) "High‐dimensional coexistence based on individual variation: a synthesis of evidence." Ecological Monographs 80, no. 4 : 569-608. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1541.1 Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux (2023a) "Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure." bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032 Camille Girard‐Tercieux, Isabelle Maréchaux, Adam T. Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Joannès Guillemot et al. (2023b) "Rethinking the nature of intraspecific variability and its consequences on species coexistence." Ecology and Evolution 13, no. 3 : e9860. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9860 Allan Raffard, Frédéric Santoul, Julien Cucherousset, and Simon Blanchet. (2019) "The community and ecosystem consequences of intraspecific diversity: A meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 94, no. 2: 648-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12472 | Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure | Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux | <p>The role of intraspecific variability (IV) in shaping community dynamics and species coexistence has been intensively discussed over the past decade and modelling studies have played an important role in that respect. However, these studies oft... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2022-08-07 12:51:30 | View | |

16 Sep 2019

Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA samplingMarie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/385120Words matter: extensive misapplication of "non-invasive" in describing DNA sampling methods, and proposed clarifying termsRecommended by Thomas Wilson Sappington based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe ability to successfully sequence trace quantities of environmental DNA (eDNA) has provided unprecedented opportunities to use genetic analyses to elucidate animal ecology, behavior, and population structure without affecting the behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal sampled. Hair associated with an animal track in the snow, the shed exoskeleton of an insect, or a swab of animal scat are all examples of non-invasive methods to collect eDNA. Despite the seemingly uncomplicated definition of "non-invasive" as proposed by Taberlet et al. [1], Lefort et al. [2] highlight that its appropriate application to sampling methods in practice is not so straightforward. For example, collecting scat left behind on the forest floor by a mammal could be invasive if feces is used by that species to mark territorial boundaries. Other collection strategies such as baited DNA traps to collect hair, capturing and handling an individual to swab or stimulate emission of a body fluid, or removal of a presumed non essential body part like a feather, fish scale, or even a leg from an insect are often described as "non-invasive" sampling methods. However, such methods cannot be considered truly non-invasive. At a minimum, attracting or capturing and handling an animal to obtain a DNA sample interrupts its normal behavioral routine, but additionally can cause both acute and long-lasting physiological and behavioral stress responses and other effects. Even invertebrates exhibit long-term hypersensitization after an injury, which manifests as heightened vigilance and enhanced escape responses [3-5]. References [1] Taberlet P., Waits L. P. and Luikart G. 1999. Noninvasive genetic sampling: look before you leap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 323-327. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01637-7 | Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling | Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer | <p>The use of DNA data is ubiquitous across animal sciences. DNA may be obtained from an organism for a myriad of reasons including identification and distinction between cryptic species, sex identification, comparisons of different morphocryptic ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Molecular ecology, Zoology | Thomas Wilson Sappington | 2018-11-30 13:33:31 | View | |

03 Apr 2020

Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)Frank Knight, Cristin Connor, Ramji Venkataramanan, Robert J. Asher https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.50971Is vertebral count in mammals influenced by developmental temperature? A study with Dasypus novemcinctusRecommended by Mar Sobral based on reviews by Darin Croft and ?Mammals show a very low level of variation in vertebral count, both among and within species, in comparison to other vertebrates [1]. Jordan’s rule for fishes states that the vertebral number among species increases with latitude, due to ambient temperatures during development [2]. Temperature has also been shown to influence vertebral count within species in fish [3], amphibians [4], and birds [5]. However, in mammals the count appears to be constrained, on the one hand, by a possible relationship between the development of the skeleton and the proliferations of cell lines with associated costs (neural malformations, cancer etc., [6]), and on the other by the cervical origin of the diaphragm [7]. References [1] Hautier L, Weisbecker V, Sánchez-Villagra MR, Goswami A, Asher RJ (2010) Skeletal development in sloths and the evolution of mammalian vertebral patterning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 18903–18908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010335107 | Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) | Frank Knight, Cristin Connor, Ramji Venkataramanan, Robert J. Asher | <p>The nine banded armadillo (*Dasypus novemcinctus*) is the only xenarthran mammal to have naturally expanded its range into the middle latitudes of the USA. It is not known to hibernate, but has been associated with unusually labile core body te... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Physiology, Zoology | Mar Sobral | 2019-11-22 22:57:31 | View | |

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View | |

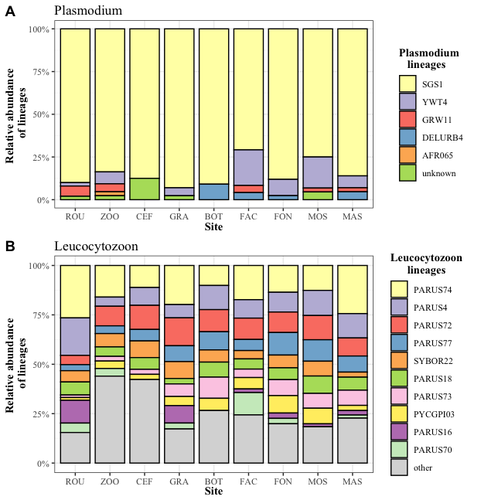

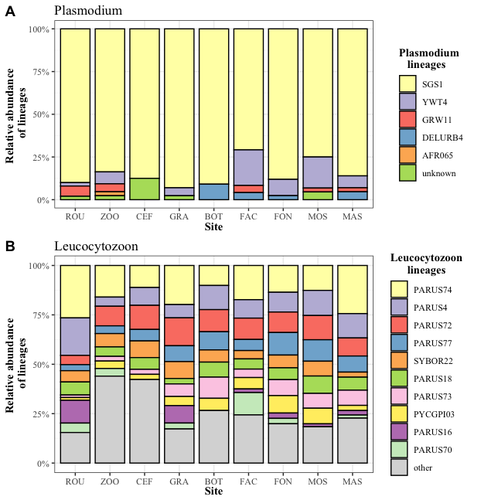

01 Mar 2024

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle