Latest recommendations

| Id▼ | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Nov 2023

The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabirdKarine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439On the road to adulthood: exploring progressive changes in foraging behaviour during post-fledging immaturity using remote trackingRecommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Juliet Lamb and 1 anonymous reviewerIn most vertebrate species, the period of life spanning from departure from the growing site until reaching a more advanced life stage (immature or adult) is critical. During this period, juveniles are often highly vulnerable because they have not reached the morphological, physiological and behavioural maturity levels of adults yet and are therefore at high risk of mortality, e.g. through starvation, depredation or competition (e.g. Marchetti & Price 1989, Wunderle 1991, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016). In line with this, juvenile survival is most often far lower than adult survival (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992). In species with parental care, juveniles have to acquire behavioural independence from their parents and possibly establish their own territory during this period of life. Very often, this is also the period that is least well-known in the life cycle (Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016) because of reduced accessibility to individuals and/or adoption of low conspicuous behaviours. Therefore, our understanding of how juveniles acquire typical adult behaviours and how this progressively increases their survival prospects is still very limited (Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), and questions such as the length of this transition period or the cognitive (e.g. learning, memorization) mechanisms involved remain largely unresolved. This is particularly true regarding the acquisition of independent foraging behaviour (Marchetti & Price 1989). Because direct observations of juvenile behaviours are usually very difficult except in specific situations or at the cost of an enormous effort, the use of remote tracking devices can be particularly appealing in this context (e.g. Ponchon et al. 2013, Kays et al. 2015). Over the past decades, technical advances have allowed the monitoring of not only individuals’ movements at both large and small spatial scales but also their activities and behaviours based on different parameters recording e.g. speed of movement or diving depth (Whitford & Klimley 2019). Device miniaturization has in particular allowed smaller species to be equipped and/or longer periods of time to be monitored (e.g. Naef-Daenzer et al. 2005). This has opened up whole fields of research, and has been particularly used on marine seabirds. In these species, individuals are most often inaccessible when at sea, representing most of the time outside (and even within) the breeding season, and the life cycle of these long-lived species can include an extended immature period (up to many years) during which most of them will remain unseen, until they come back as breeders or pre-breeders (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992, Oro & Martínez-Abraín 2009). Survival has been found to increase gradually with age in these species before reaching high values characteristic of the adult stage. However, the mechanisms underlying this increase are still to be deciphered. The study by Delord et al. (2023) builds upon the hypothesis that juveniles gradually learn foraging techniques and movement strategies, improving their foraging efficiency, as previous data on flight parameters seemed to show in different long-lived bird species. Yet, these previous studies obtained data over a limited period of time, i.e. a few months at best. Whether these data could capture the whole dynamics of the progressive acquisition of foraging and movement skills can only be assessed by measuring behaviour over a longer time period and comparing it to similar data in adults, to account for seasonal variation in relation to both resource availability and energetic demands, e.g. due to molt. The present study (Delord et al. 2023) addresses these questions by taking advantage of longer-lasting recordings of the location and activity of juvenile, immature and adult birds obtained simultaneously to investigate changes over time in juvenile behaviour and thereby provide hints about how young progressively acquire foraging skills. This study is performed on Amsterdam albatrosses, a highly endangered long-lived sea bird, with obvious conservation issues (Thiebot et al. 2015). The results show progressive changes in foraging effort over the first two months after departure from the birth colony, but large differences remain between life stages over a much longer time frame. They also reveal strong variations between sexes and over time in the year. Overall, this study, therefore, confirms the need for very long-term data to be collected in order to address the question of progressive behavioural maturation and associated survival consequences in such species with strongly deferred maturity. Ideally, the same individuals should be monitored over different life stages, from the juvenile period up to adulthood, but this would require further technical development to release the issue of powering duration limitation. As reviewers emphasized in the first review round, one main challenge now remains to ascertain the outcome of the observed behavioural changes in foraging behaviour: we expect them to reflect improvement in foraging skills and thus performance of juveniles over time, but this would need to be tested. Collecting data on foraging efficiency is yet another challenge, that future technical developments may also help overcome. Importantly also, data were available only for individuals that could be caught again because the tracking device had to be retrieved from the bird. Here, a substantial fraction of the loggers (one-fifth) could not be found again (Delord et al. 2023). To what extent the birds for which no data could be obtained are a random sample of the equipped birds would also need to be assessed. The further development of remote tracking techniques allowing data to be downloaded from a long distance should help further exploration of behavioural ontogeny of juveniles while maturing and its survival consequences. Because the maturation process explored here is likely to show very different characteristics (e.g. timing and speed) in smaller / shorter-lived species (see Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), the development of miniaturization is also expected to allow further investigation of post-fledging behavioural maturation in a wider range of bird species. Our understanding of this crucial life phase in different types of species should thus continue to progress in the coming years. References Cox W. A., Thompson F. R. III, Cox A. S. & Faaborg J. 2014. Post-fledging survival in passerine birds and the value of post-fledging studies to conservation. Journal of Wildlife Management, 78: 183-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.670 Delord K., Weimerskirch H. & Barbraud C. 2023. The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird. bioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439 Kays R., Crofoot M. C., Jetz W. & Wikelski M. 2015. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science, 348 (6240). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2478 Marchetti K: & Price T. 1989. Differences in the foraging of juvenile and adult birds: the importance of developmental constraints. Biological Reviews, 64: 51-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1989.tb00638.x Naef-Daenzer B., Fruh D., Stalder M., Wetli P. & Weise E. 2005. Miniaturization (0.2 g) and evaluation of attachment techniques of telemetry transmitters. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 208: 4063–4068. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01870 Naef-Daenzer B. & Grüebler M. U. 2016. Post-fledging survival of altricial birds: ecological determinants and adaptation. Journal of Field Ornithology, 87: 227-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofo.12157 Oro D. & Martínez-Abraín A. 2009. Ecology and behavior of seabirds. Marine Ecology, pp.364-389. Ponchon A., Grémillet D., Doligez B., Chambert T., Tveera T., Gonzàles-Solìs J & Boulinier T. 2013. Tracking prospecting movements involved in breeding habitat selection: insights, pitfalls and perspectives. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00259.x Thiebot J.-B., Delord K., Barbraud C., Marteau C. & Weimerskirch H. 2015. 167 individuals versus millions of hooks: bycatch mitigation in longline fisheries underlies conservation of Amsterdam albatrosses. Aquatic Conservation 26: 674-688. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2578 Whitford M & Klimley A. P. An overview of behavioral, physiological, and environmental sensors used in animal biotelemetry and biologging studies. Animal Biotelemetry, 7: 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0189-z Wooller R.D., Bradley J. S. & Croxall J. P. 1992. Long-term population studies of seabirds. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 111-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(92)90143-y Wunderle J. M. 1991. Age-specific foraging proficiency in birds. Current Ornithology, 8: 273-324. | The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird | Karine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The transition to independent foraging represents an important developmental stage in the life cycle of most vertebrate animals. Juveniles differ from adults in various life history traits and tend to survive less w... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Foraging, Ontogeny | Blandine Doligez | 2021-10-26 07:51:49 | View | |

31 Oct 2022

Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing dataAdam L. Mahood, Maxwell Benjamin Joseph, Anna Spiers, Michael J. Koontz, Nayani Ilangakoon, Kylen Solvik, Nathan Quarderer, Joe McGlinchy, Victoria Scholl, Lise St. Denis, Chelsea Nagy, Anna Braswell, Matthew W. Rossi, Lauren Herwehe, Leah wasser, Megan Elizabeth Cattau, Virginia Iglesias, Fangfang Yao, Stefan Leyk, Jennifer Balch https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/kehqzPreventing misuse of high-resolution remote sensing dataRecommended by Eric Goberville based on reviews by Jane Wyngaard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jane Wyngaard and 1 anonymous reviewer

To observe, characterise, identify, understand, predict... This is the approach that researchers follow every day. This sequence is tirelessly repeated as the biological model, the targeted ecosystem and/or the experimental, environmental or modelling conditions change. This way of proceeding is essential in a world of rapid change in response to the frenetic pace of intensifying pressures and forcings that impact ecosystems. To better understand our Earth and the dynamics of its components, to map ecosystems and diversity patterns, and to identify changes, humanity had to demonstrate inventiveness and defy gravity. Gustave Hermite and Georges Besançon were the first to launch aloft balloons equipped with radio transmitters, making possible the transmission of meteorological data to observers in real time [1]. The development of aviation in the middle of the 20th century constituted a real leap forward for the frequent acquisition of aerial observations, leading to a significant improvement in weather forecasting models. The need for systematic collection of data as holistic as possible – an essential component for the observation of complex biological systems - has resulted in pushing the limits of technological prowess. The conquest of space and the concurrent development of satellite observations has largely contributed to the collection of a considerable mass of data, placing our Earth under the "macroscope" - a concept introduced to ecology in the early 1970s by Howard T. Odum (see [2]), and therefore allowing researchers to move towards a better understanding of ecological systems, deterministic and stochastic patterns … with the ultimate goal of improving management actions [2,3]. Satellite observations have been carried out for nearly five decades now [3] and have greatly contributed to a better qualitative and quantitative understanding of the functioning of our planet, its diversity, its climate... and to a better anticipation of possible future changes (e.g., [4-7]). This access to rich and complex sources of information, for which both spatial and temporal resolutions are increasingly fine, results in the implementation of increasingly complex computation-based analyses, in order to meet the need for a better understanding of ecological mechanisms and processes, and their possible changes. Steven Levitt stated that "Data is one of the most powerful mechanisms for telling stories". This is so true … Data should not be used as a guide to thinking and a critical judgment at each stage of the data exploitation process should not be neglected. This is what Mahood et al. [8] rightly remind us in their article "Ten simple rules for working with high-resolution remote sensing data" in which they provide the fundamentals to consider when working with data of this nature, a still underutilized resource in several topics, such as conservation biology [3]. In this unconventional article, presented in a pedagogical way, the authors remind different generations of readers how satellite data should be handled and processed. The authors aim to make the readers aware of the most frequent pitfalls encouraging them to use data adapted to their original question, the most suitable tools/methods/procedures, to avoid methodological overkill, and to ensure both ethical use of data and transparency in the research process. While access to high-resolution data is increasingly easy thanks to the implementation of dedicated platforms [4], and because of the development of easy-to-use processing software and pipelines, it is important to take the time to recall some of the essential rules and guidelines for managing them, from new users with little or no experience who will find in this article the recommendations, resources and advice necessary to start exploiting remote sensing data, to more experienced researchers. References [1] Jeannet P, Philipona R, and Richner H (2016). 8 Swiss upper-air balloon soundings since 1902. In: Willemse S, Furger M (2016) From weather observations to atmospheric and climate sciences in Switzerland: Celebrating 100 years of the Swiss Society for Meteorology. vdf Hochschulverlag AG. [2] Odum HT (2007) Environment, Power, and Society for the Twenty-First Century: The Hierarchy of Energy. Columbia University Press. [3] Boyle SA, Kennedy CM, Torres J, Colman K, Pérez-Estigarribia PE, Sancha NU de la (2014) High-Resolution Satellite Imagery Is an Important yet Underutilized Resource in Conservation Biology. PLOS ONE, 9, e86908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086908 [4] Le Traon P-Y, Antoine D, Bentamy A, Bonekamp H, Breivik LA, Chapron B, Corlett G, Dibarboure G, DiGiacomo P, Donlon C, Faugère Y, Font J, Girard-Ardhuin F, Gohin F, Johannessen JA, Kamachi M, Lagerloef G, Lambin J, Larnicol G, Le Borgne P, Leuliette E, Lindstrom E, Martin MJ, Maturi E, Miller L, Mingsen L, Morrow R, Reul N, Rio MH, Roquet H, Santoleri R, Wilkin J (2015) Use of satellite observations for operational oceanography: recent achievements and future prospects. Journal of Operational Oceanography, 8, s12–s27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2015.1022050 [5] Turner W, Rondinini C, Pettorelli N, Mora B, Leidner AK, Szantoi Z, Buchanan G, Dech S, Dwyer J, Herold M, Koh LP, Leimgruber P, Taubenboeck H, Wegmann M, Wikelski M, Woodcock C (2015) Free and open-access satellite data are key to biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 182, 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.048 [6] Melet A, Teatini P, Le Cozannet G, Jamet C, Conversi A, Benveniste J, Almar R (2020) Earth Observations for Monitoring Marine Coastal Hazards and Their Drivers. Surveys in Geophysics, 41, 1489–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-020-09594-5 [7] Zhao Q, Yu L, Du Z, Peng D, Hao P, Zhang Y, Gong P (2022) An Overview of the Applications of Earth Observation Satellite Data: Impacts and Future Trends. Remote Sensing, 14, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14081863 [8] Mahood AL, Joseph MB, Spiers A, Koontz MJ, Ilangakoon N, Solvik K, Quarderer N, McGlinchy J, Scholl V, Denis LS, Nagy C, Braswell A, Rossi MW, Herwehe L, Wasser L, Cattau ME, Iglesias V, Yao F, Leyk S, Balch J (2021) Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing data. OSFpreprints, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/kehqz | Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing data | Adam L. Mahood, Maxwell Benjamin Joseph, Anna Spiers, Michael J. Koontz, Nayani Ilangakoon, Kylen Solvik, Nathan Quarderer, Joe McGlinchy, Victoria Scholl, Lise St. Denis, Chelsea Nagy, Anna Braswell, Matthew W. Rossi, Lauren Herwehe, Leah wasser,... | <p>Researchers in Earth and environmental science can extract incredible value from high-resolution (sub-meter, sub-hourly or hyper-spectral) remote sensing data, but these data can be difficult to use. Correct, appropriate and competent use of su... |  | Biogeography, Landscape ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Eric Goberville | 2021-10-19 21:41:22 | View | |

12 Sep 2023

Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patternsYuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913The impact of process at different scales on diversity and ecosystem functioning: a huge challengeRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer

Scale is a big topic in ecology [1]. Environmental variation happens at particular scales. The typical scale at which organisms disperse is species-specific, but, as a first approximation, an ensemble of similar species, for instance, trees, could be considered to share a typical dispersal scale. Finally, characteristic spatial scales of species interactions are, in general, different from the typical scales of dispersal and environmental variation. Therefore, conceptually, we can distinguish these three characteristic spatial scales associated with three different processes: species selection for a given environment (E), dispersal (D), and species interactions (I), respectively. From the famous species-area relation to the spatial distribution of biomass and species richness, the different macro-ecological patterns we usually study emerge from an interplay between dispersal and local interactions in a physical environment that constrains species establishment and persistence in every location. To make things even more complicated, local environments are often modified by the species that thrive in them, which establishes feedback loops. It is usually assumed that local interactions are short-range in comparison with species dispersal, and dispersal scales are typically smaller than the scales at which the environment varies (I < D < E, see [2]), but this should not always be the case. The authors of this paper [2] relax this typical assumption and develop a theoretical framework to study how diversity and ecosystem functioning are affected by different relations between the typical scales governing interactions, dispersal, and environmental variation. This is a huge challenge. First, diversity and ecosystem functioning across space and time have been empirically characterized through a wide variety of macro-ecological patterns. Second, accommodating local interactions, dispersal and environmental variation and species environmental preferences to model spatiotemporal dynamics of full ecological communities can be done also in a lot of different ways. One can ask if the particular approach suggested by the authors is the best choice in the sense of producing robust results, this is, results that would be predicted by alternative modeling approaches and mathematical analyses [3]. The recommendation here is to read through and judge by yourself. The main unusual assumption underlying the model suggested by the authors is non-local species interactions. They introduce interaction kernels to weigh the strength of the ecological interaction with distance, which gives rise to a system of coupled integro-differential equations. This kernel is the key component that allows for control and varies the scale of ecological interactions. Although this is not new in ecology [4], and certainly has a long tradition in physics ---think about the electric or the gravity field, this approach has been widely overlooked in the development of the set of theoretical frameworks we have been using over and over again in community ecology, such as the Lotka-Volterra equations or, more recently, the metacommunity concept [5]. In Physics, classic fields have been revised to account for the fact that information cannot travel faster than light. In an analogous way, a focal individual cannot feel the presence of distant neighbors instantaneously. Therefore, non-local interactions do not exist in ecological communities. As the authors of this paper point out, they emerge in an effective way as a result of non-random movements, for instance, when individuals go regularly back and forth between environments (see [6], for an application to infectious diseases), or even migrate between regions. And, on top of this type of movement, species also tend to disperse and colonize close (or far) environments. Individual mobility and dispersal are then two types of movements, characterized by different spatial-temporal scales in general. Species dispersal, on the one hand, and individual directed movements underlying species interactions, on the other, are themselves diverse across species, but it is clear that they exist and belong to two distinct categories. In spite of the long and rich exchange between the authors' team and the reviewers, it was not finally clear (at least, to me and to one of the reviewers) whether the model for the spatio-temporal dynamics of the ecological community (see Eq (1) in [2]) is only presented as a coupled system of integro-differential equations on a continuous landscape for pedagogical reasons, but then modeled on a discrete regular grid for computational convenience. In the latter case, the system represents a regular network of local communities, becomes a system of coupled ODEs, and can be numerically integrated through the use of standard algorithms. By contrast, in the former case, the system is meant to truly represent a community that develops on continuous time and space, as in reaction-diffusion systems. In that case, one should keep in mind that numerical instabilities can arise as an artifact when integrating both local and non-local spatio-temporal systems. Spatial patterns could be then transient or simply result from these instabilities. Therefore, when analyzing spatiotemporal integro-differential equations, special attention should be paid to the use of the right numerical algorithms. The authors share all their code at https://zenodo.org/record/5543191, and all this can be checked out. In any case, the whole discussion between the authors and the reviewers has inherent value in itself, because it touches on several limitations and/or strengths of the author's approach, and I highly recommend checking it out and reading it through. Beyond these methodological issues, extensive model explorations for the different parameter combinations are presented. Several results are reported, but, in practice, what is then the main conclusion we could highlight here among all of them? The authors suggest that "it will be difficult to manage landscapes to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functioning simultaneously, despite their causative relationship", because, first, "increasing dispersal and interaction scales had opposing References [1] Levin, S. A. 1992. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941447 [2] Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain. 2023. Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913 [3] Baron, J. W. and Galla, T. 2020. Dispersal-induced instability in complex ecosystems. Nature Communications 11, 6032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19824-4 [4] Cushing, J. M. 1977. Integrodifferential equations and delay models in population dynamics [5] M. A. Leibold, M. Holyoak, N. Mouquet, P. Amarasekare, J. M. Chase, M. F. Hoopes, R. D. Holt, J. B. Shurin, R. Law, D. Tilman, M. Loreau, A. Gonzalez. 2004. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters, 7(7): 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x [6] M. Pardo-Araujo, D. García-García, D. Alonso, and F. Bartumeus. 2023. Epidemic thresholds and human mobility. Scientific reports 13 (1), 11409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38395-0 | Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns | Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain | <p style="text-align: justify;">Ecology is a science of scale, which guides our description of both ecological processes and patterns, but we lack a systematic understanding of how process scale and pattern scale are connected. Recent calls for a ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Ecosystem functioning, Landscape ecology, Theoretical ecology | David Alonso | 2021-10-13 23:24:45 | View | ||

02 Aug 2022

The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8naWhen do dominant females have higher breeding success than subordinates? A meta-analysis across social mammals.Recommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this meta-analysis, Shivani et al. [1] investigate 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals and 2) whether this relationship varies according to a) life history traits (e.g., stronger for species with large litter size), b) ecological conditions (e.g., stronger when resources are limited) and c) the social environment (e.g., stronger for cooperative breeders than for plural breeders). Generally, the results are consistent with their predictions, except there was no clear support for this relationship to be conditional on the ecological conditions. considered As I have previously recommended the preregistration of this study [2,3], I do not have much to add here, as such recommendation should not depend on the outcome of the study. What I would like to recommend is the whole scientific process performed by the authors, from preregistration sent for peer review, to preprint submission and post-study peer review. It is particularly recommendable to notice that this project was a Masters student project, which shows that it is possible and worthy to preregister studies, even for such rather short-term projects. I strongly congratulate the authors for choosing this process even for an early career short-term project. I think it should be made possible for short-term students to conduct a preregistration study as a research project, without having to present post-study results. I hope this study can encourage a shift in the way we sometimes evaluate students’ projects. I also recommend the readers to look into the whole pre- and post- study reviewing history of this manuscript and the associated preregistration, as it provides a better understanding of the process and a good example of the associated challenges and benefits [4]. It was a really enriching experience and I encourage others to submit and review preregistrations and registered reports!

References [1] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2022). The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals. EcoEvoRxiv, rc8na, ver. 10 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8na [2] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2020). Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version 1.2 on 07 July 2020. https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.html [3] Paquet, M. (2020) Why are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammals. Peer Community in Ecology, 100056. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100056 [4] Parker, T., Fraser, H., & Nakagawa, S. (2019). Making conservation science more reliable with preregistration and registered reports. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 747-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13342 | The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses | Matthieu Paquet | 2021-10-13 18:26:42 | View | |

03 Mar 2022

Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than its age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea)sylvain blouet, Katell Guizien, lorenzo Bramanti https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.08.463669A longer-term view on benthic communities on artificial reefs: it’s all about locationRecommended by James Davis Reimer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this study by Blouet, Bramanti, and Guizen (2022), the authors aim to tackle a long-standing data gap regarding research on marine benthic communities found on artificial reefs. The study is well thought out, and should serve as an important reference on this topic going forward. Blouet S, Bramanti L, Guizien K (2022) Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than shape, age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea). bioRxiv, 2021.10.08.463669, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.08.463669 | Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than its age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea) | sylvain blouet, Katell Guizien, lorenzo Bramanti | <p>Artificial reefs (ARs) have been used to support fishing activities. Sessile invertebrates are essential components of trophic networks within ARs, supporting fish productivity. However, colonization by sessile invertebrates is possible only af... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Colonization, Ecological successions, Life history, Marine ecology | James Davis Reimer | 2021-10-11 10:21:36 | View | |

11 Mar 2022

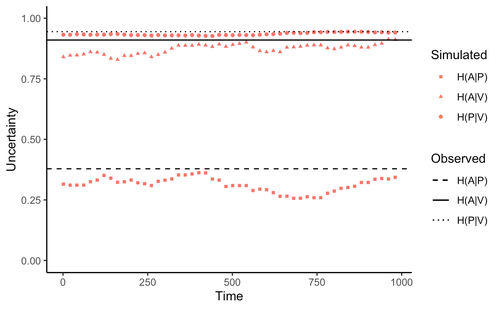

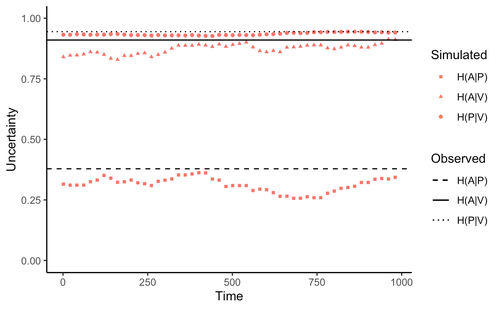

Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities”Ethan Bass, André Kessler https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/xsbtmDoes information theory inform chemical arms race communication?Recommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Claudio Ramirez and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the long-standing questions in evolutionary ecology is on the mechanisms involved in arms race coevolution. One way to address this question is to understand the conditions under which one species evolves traits in response to the presence of a second species and so on. However, specialized pairwise interactions are by far less common in nature than interactions involving a higher number of interacting species (Bascompte, Jordano 2013). While interactions between large sets of species are the norm rather than the exception in mutualistic (pollination, seed dispersal), and antagonist (herbivory, parasitism) relationships, few is known on the way species identify, process, and respond to information provided by other interacting species under field conditions (Schaefer, Ruxton 2011). Zu et al. (2020) addressed this general question by developing an interesting information theory-based approach that hypothesized conditional entropy in chemical communication plays a role as proxy of fitness in plant-herbivore communities. More specifically, plant fitness was assumed to be related to the efficiency to code signals by plant species, and herbivore fitness to the capacity to decode plant signals. In this way, from the plant perspective, the elaboration of plant signals that elude decoding by herbivores is expected to be favored, as herbivores are expected to attack plants with simple chemical signals. The empirical observation upon which the model was tested was the redundancy in volatile organic compounds (VOC) found across plant species in a plant-herbivore community. Interestingly, Zu et al.’s model predicted successfully that VOC redundancy in the plant community associates with increased conditional entropy, which conveys herbivore confusion and plant protection against herbivory. In this way, plant species that evolve VOCs already present in the community might be benefitted, ultimately leading to the patterns of VOC redundancy commonly observed in nature. Bass & Kessler performed a series of interesting observations on Zu et al. (2020), that can be organized along three lines of reasoning. First, from an evolutionary perspective, Bass & Kessler note the important point that accepting that conditional information entropy, estimated from the contribution of every plant species to volatile redundancy implies that average plant fitness seems to depend on community-level properties (i.e., what the other species in the community are doing) rather than on population-level characteristics (I.e., what the individuals belonging a population are doing). While the level at which selection acts upon is a longstanding debate (e.g., Goodnight, 1990; Williams, 1992), the model seems to contradict one of the basic tenets of Darwinian evolution. The extent to which this important observation invalidates the contribution of Zu et al. (2020) is open to scrutiny. However, one can indulge the evolutionary criticism by arguing that every theoretical model performs a number of assumptions to preserve the simplicity of analyses. Furthermore, even accepting the criticism, the overall information-based framework is valuable as it provides a fresh perspective to the way coding and decoding chemical information in plant-herbivore interactions may result in arm race coevolution. The question to be assessed by members of the scientific community is how strong the evolutionary assumptions are to be acceptable. A second line of reasoning involves consideration of additional routes of chemical information transfer. If chemical volatiles are involved in another ecological function unrelated to arm race (as they are) such as toxicity, crypsis, aposematism, etc., the conditional information indices considered as proxy to plant and herbivore fitness may be only secondarily related to arms race. This is an interesting observation, which suggests that VOC production may have more than one ecological function, as it often happens in “pleiotropic” traits (Strauss, Irwin 2004). This is an exciting avenue for future research. Finally, a third category of comments involves the relationship between conditional information entropy and plant and herbivore fitness. Bass & Kessler developed a Bayesian treatment of the community-level information developed by Zu et al. (2020) that permitted to estimate fitness on a species rather than community level. Their results revealed that community conditional entropies fail to align with species-level indices, suggesting that conclusions of Strauss & Irwin (2004) are not commensurate with fitness at the species level, where the analysis seems to be pertinent. In general, I strongly recommend Bass & Kessler’s contribution as it provides a series of observations and new perspectives to Zu et al. (2020). Rather than restricting their manuscript to blind criticisms, Bass & Kessler provides new interesting perspectives, which is always welcome as it improves the value and scope of the original work. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691131269.001.0001 Bass E, Kessler A (2022) Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities.” EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/xsbtm Goodnight CJ (1990) Experimental Studies of Community Evolution I: The Response to Selection at the Community Level. Evolution, 44, 1614–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03850.x Schaefer HM, Ruxton GD (2011) Plant-Animal Communication. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199563609.001.0001 Strauss SY, Irwin RE (2004) Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Multispecies Plant-Animal Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 435–466. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130215 Williams GC (1992) Natural Selection: Domains, Levels, and Challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. Zu P, Boege K, del-Val E, Schuman MC, Stevenson PC, Zaldivar-Riverón A, Saavedra S (2020) Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities. Science, 368, 1377–1381. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba2965 | Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities” | Ethan Bass, André Kessler | <p style="text-align: justify;">Zu et al (Science, 19 Jun 2020, p. 1377) propose that an ‘information arms-race’ between plants and herbivores explains plant-herbivore communication at the community level. However, the analysis presented here show... |  | Chemical ecology, Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Rodrigo Medel | 2021-10-02 06:06:07 | View | |

12 May 2022

Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapesYasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fujaco, Mariangela Garcia Praca Leite, Joice Paiva Vidigal Martins, Graziella Franca Monteiro, Rodolfo Dirzo https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375Complex but positive diversity - ecosystem functioning relationships in Riparian tropical forestsRecommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many ecological drivers can impact ecosystem functionality and multifunctionality, with the latter describing the joint impact of different functions on ecosystem performance and services. It is now generally accepted that taxonomically richer ecosystems are better able to sustain high aggregate functionality measures, like energy transfer, productivity or carbon storage (Buzhdygan 2020, Naeem et al. 2009), and different ecosystem services (Marselle et al. 2021) than those that are less rich. Antonini et al. (2022) analysed an impressive dataset on animal and plant richness of tropical riparian forests and abundances, together with data on key soil parameters. Their work highlights the importance of biodiversity on functioning, while accounting for a manifold of potentially covarying drivers. Although the key result might not come as a surprise, it is a useful contribution to the diversity - ecosystem functioning topic, because it is underpinned with data from tropical habitats. To date, most analyses have focused on temperate habitats, using data often obtained from controlled experiments. The paper also highlights that diversity–functioning relationships are complicated. Drivers of functionality vary from site to site and each measure of functioning, including parameters as demonstrated here, can be influenced by very different sets of predictors, often associated with taxonomic and trait diversity. Single correlative comparisons of certain aspects of diversity and functionality might therefore return very different results. Antonini et al. (2022) show that, in general, using 22 predictors of functional diversity, varying predictor subsets were positively associated with soil functioning. Correlational analyses alone cannot resolve the question of causal link. Future studies should therefore focus on inferring precise mechanisms behind the observed relationships, and the environmental constraints on predictor subset composition and strength. References Antonini Y, Beirão MV, Costa FV, Azevedo CS, Wojakowski MM, Kozovits AR, Pires MRS, Sousa HC de, Messias MCTB, Fujaco MA, Leite MGP, Vidigal JP, Monteiro GF, Dirzo R (2022) Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2021.09.08.459375, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375 Buzhdygan OY, Meyer ST, Weisser WW, Eisenhauer N, Ebeling A, Borrett SR, Buchmann N, Cortois R, De Deyn GB, de Kroon H, Gleixner G, Hertzog LR, Hines J, Lange M, Mommer L, Ravenek J, Scherber C, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Scheu S, Schmid B, Steinauer K, Strecker T, Tietjen B, Vogel A, Weigelt A, Petermann JS (2020) Biodiversity increases multitrophic energy use efficiency, flow and storage in grasslands. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1123-8 Marselle MR, Hartig T, Cox DTC, de Bell S, Knapp S, Lindley S, Triguero-Mas M, Böhning-Gaese K, Braubach M, Cook PA, de Vries S, Heintz-Buschart A, Hofmann M, Irvine KN, Kabisch N, Kolek F, Kraemer R, Markevych I, Martens D, Müller R, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Potts JM, Stadler J, Walton S, Warber SL, Bonn A (2021) Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International, 150, 106420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106420 Naeem S, Bunker DE, Hector A, Loreau M, Perrings C (Eds.) (2009) Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning, and Human Wellbeing: An Ecological and Economic Perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199547951.001.0001 | Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes | Yasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fuja... | <ol> <li style="text-align: justify;">Restoration of tropical riparian forests is challenging, since these ecosystems are the most diverse, dynamic, and complex physical and biological terrestrial habitats. This study tested whether biodiversity ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecological successions, Ecosystem functioning, Terrestrial ecology | Werner Ulrich | 2021-09-10 10:51:23 | View | |

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

01 Mar 2022

Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiringTimothée Poisot https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2How to evaluate and interpret the contribution of species turnover and interaction rewiring when comparing ecological networks?Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer

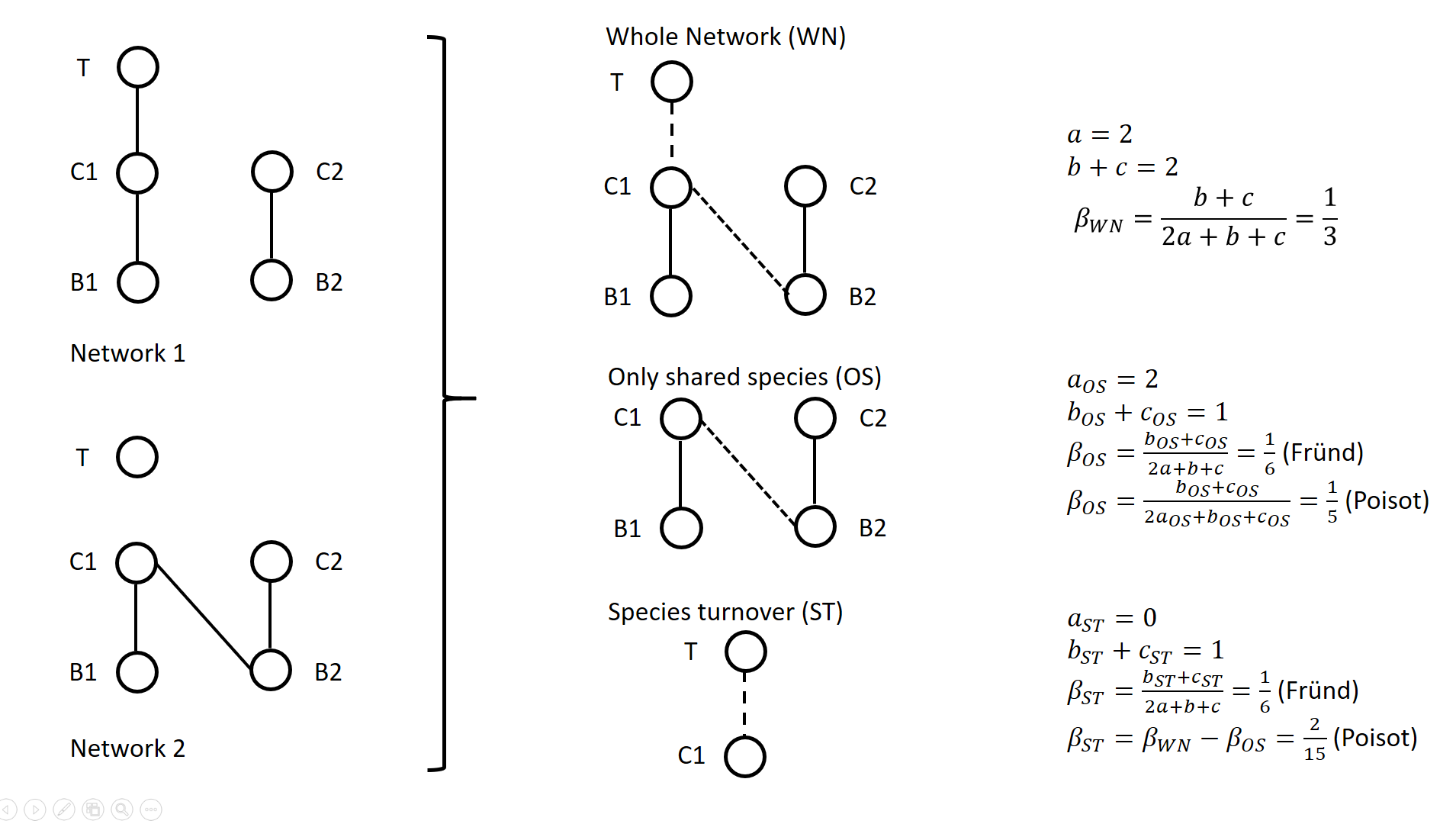

A network includes a set of vertices or nodes (e.g., species in an interaction network), and a set of edges or links (e.g., interactions between species). Whether and how networks vary in space and/or time are questions often addressed in ecological research. Two ecological networks can differ in several extents: in that species are different in the two networks and establish new interactions (species turnover), or in that species that are present in both networks establish different interactions in the two networks (rewiring). The ecological meaning of changes in network structure is quite different according to whether species turnover or interaction rewiring plays a greater role. Therefore, much attention has been devoted in recent years on quantifying and interpreting the relative changes in network structure due to species turnover and/or rewiring. Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to partition the global variation in structure between networks, \( \beta_{WN} \) (WN = Whole Network) into two terms: \( \beta_{OS} \) (OS = Only Shared species) and \( \beta_{ST} \) (ST = Species Turnover), such as \( \beta_{WN} = \beta_{OS} + \beta_{ST} \). The calculation lays on enumerating the interactions between species that are common or not to two networks, as illustrated on Figure 1 for a simple case. Specifically, Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to use a Sorensen type measure of network dissimilarity, i.e., \( \beta_{WN} = \frac{a+b+c}{(2a+b+c)/2} -1=\frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} \) , where \( a \) is the number of interactions shared between the networks, while \( b \) and \( c \) are interaction numbers unique to one and the other network, respectively. \( \beta_{OS} \) is calculated based on the same formula, but only for the subnetworks including the species common to the two networks, in the form \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a_{OS}+b_{OS}+c_{OS}} \) (e.g., Fig. 1). \( \beta_{ST} \) is deduced by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and represents in essence a "dissimilarity in interaction structure introduced by dissimilarity in species composition" (Poisot et al. 2012).

Figure 1. Ecological networks exemplified in Fründ (2021) and discussed in Poisot (2022). a is the number of shared links (continuous lines in right figures), while b+c is the number of edges unique to one or the other network (dashed lines in right figures). Alternatively, Fründ (2021) proposed to define \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a+b+c} \) and \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} \), where \( b_{ST}=b-b_{OS} \) and \( c_{ST}=c-c_{OS} \) , so that the components \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) have the same denominator. In this way, Fründ (2021) partitioned the count of unique \( b+c=b_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST} \) interactions, so that \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) sums to \( \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} = \frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} = \beta_{WN} \). Fründ (2021) advocated that this partition allows a more sensible comparison of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \), in terms of the number of links that contribute to each component. For instance, let us consider the networks 1 and 2 in Figure 1 (left panel) such as \( a_{OS}=2 \) (continuous lines in right panel), \( b_{ST} + c_{ST} = 1 \) and \( b_{OS} + c_{OS} = 1 \) (dashed lines in right panel), and thereby \( a = 2 \), \( b+c=2 \), \( \beta_{WN} = 1/3 \). Fründ (2021) measured \( \beta_{OS}=\beta_{ST}=1/6 \) and argued that it is appropriate insofar as it reflects that the number of unique links in the OS and ST components contributing to network dissimilarity (dashed lines) are actually equal. Conversely, the formula of Poisot et al. (2012) yields \( \beta_{OS}=1/5 \), hence \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{5}=\frac{2}{15}<\beta_{OS} \). Fründ (2021) thus argued that the method of Poisot tends to underestimate the contribution of species turnover. To clarify and avoid misinterpretation of the calculation of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) in Poisot et al. (2012), Poisot (2022) provides a new, in-depth mathematical analysis of the decomposition of \( \beta_{WN} \). Poisot et al. (2012) quantify in \( \beta_{OS} \) the actual contribution of rewiring in network structure for the subweb of common species. Poisot (2022) thus argues that \( \beta_{OS} \) relates only to the probability of rewiring in the subweb, while the definition of \( \beta_{OS} \) by Fründ (2021) is relative to the count of interactions in the global network (considered in denominator), and is thereby dependent on both rewiring probability and species turnover. Poisot (2022) further clarifies the interpretation of \( \beta_{ST} \). \( \beta_{ST} \) is obtained by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and thus represents the influence of species turnover in terms of the relative architectures of the global networks and of the subwebs of shared species. Coming back to the example of Fig.1., the Poisot et al. (2012) formula posits that \( \frac{\beta_{ST}}{\beta_{WN}}=\frac{2/15}{1/3}=2/5 \), meaning that species turnover contributes two-fifths of change in network structure, while rewiring in the subweb of common species contributed three fifths. Conversely, the approach of Fründ (2021) does not compare the architectures of global networks and of the subwebs of shared species, but considers the relative contribution of unique links to network dissimilarity in terms of species turnover and rewiring. Poisot (2022) concludes that the partition proposed in Fründ (2021) does not allow unambiguous ecological interpretation of rewiring. He provides guidelines for proper interpretation of the decomposition proposed in Poisot et al. (2012). References Fründ J (2021) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: how to partition rewiring and species turnover components. Ecosphere, 12, e03653. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3653 Poisot T, Canard E, Mouillot D, Mouquet N, Gravel D (2012) The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecology Letters, 15, 1353–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12002 Poisot T (2022) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring. EcoEvoRxiv Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2 | Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring | Timothée Poisot | <p style="text-align: justify;">Despite having established its usefulness in the last ten years, the decomposition of ecological networks in components allowing to measure their β-diversity retains some methodological ambiguities. Notably, how to ... |  | Biodiversity, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2021-07-31 00:18:41 | View | |

05 Apr 2022

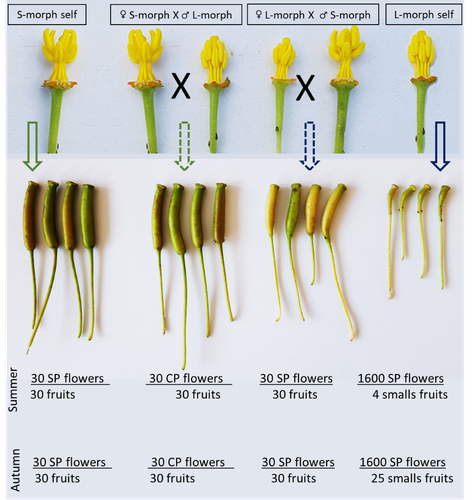

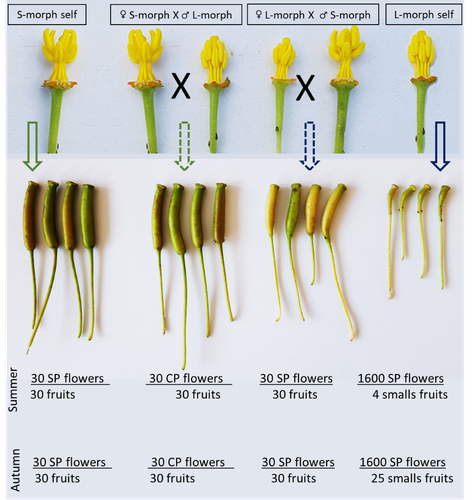

Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetalaLuis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457Water primerose (Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala) auto- and allogamy: an ecological perspectiveRecommended by Antoine Vernay based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer

Invasive plant species are widely studied by the ecologist community, especially in wetlands. Indeed, alien plants are considered one of the major threats to wetland biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019). Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G.L.Nesom & Kartesz, 2000 (Lgh) is one of them and has received particular attention for a long time (Hieda et al., 2020; Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiebaut, 2013). The ecology of this invasive species and its effect on its biotic and abiotic environment has been studied in previous works. Different processes were demonstrated to explain their invasibility such as allelopathic interference (Dandelot et al., 2008), resource competition (Gérard et al., 2014), and high phenotypic plasticity (Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiébaut, 2013), to cite a few of them. However, although vegetative reproduction is a well-known invasive process for alien plants like Lgh (Glover et al., 2015), the sexual reproduction of this species is still unclear and may help to understand the Lgh population dynamics. Portillo Lemus et al. (2021) showed that two floral morphs of Lgh co-exist in natura, involving self-compatibility for short-styled phenotype and self-incompatibility for long-styled phenotype processes. This new article (Portillo Lemus et al., 2022) goes further and details the underlying mechanisms of the sexual reproduction of the two floral morphs. Complementing their previous study, the authors have described a late self-incompatible process associated with the long-styled morph, which authorized a small proportion of autogamy. Although this represents a small fraction of the L-morph reproduction, it may have a considerable impact on the L-morph population dynamics. Indeed, authors report that “floral morphs are mostly found in allopatric monomorphic populations (i.e., exclusively S-morph or exclusively L-morph populations)” with a large proportion of L-morph populations compared to S-morph populations in the field. It may seem counterintuitive as L-morph mainly relies on cross-fecundation. Results show that L-morph autogamy mainly occurs in the fall, late in the reproduction season. Therefore, the reproduction may be ensured if no exogenous pollen reaches the stigma of L-morph individuals. It partly explains the large proportion of L-morph populations in the field. Beyond the description of late-acting self-incompatibility, which makes the Onagraceae a third family of Myrtales with this reproductive adaptation, the study raises several ecological questions linked to the results presented in the article. First, it seems that even if autogamy is possible, Lgh would favour allogamy, even in S-morph, through the faster development of pollen tubes from other individuals. This may confer an adaptative and evolutive advantage for the Lgh, increasing its invasive potential. The article shows this faster pollen tube development in S-morph but does not test the evolutive consequences. It is an interesting perspective for future research. It would also be interesting to describe cellular processes which recognize and then influence the speed of the pollen tube. Second, the importance of sexual reproduction vs vegetative reproduction would also provide information on the benefits of sexual dimorphism within populations. For instance, how fruit production increases the dispersal potential of Lgh would help to understand Lgh population dynamics and to propose adapted management practices (Delbart et al., 2013; Meisler, 2009). To conclude, the study proposes a morphological, reproductive and physiological description of the Lgh sexual reproduction process. However, underlying ecological questions are well included in the article and the ecophysiological results enlighten some questions about the role of sexual reproduction in the invasiveness of Lgh. I advise the reader to pay attention to the reviewers’ comments; the debates were very constructive and, thanks to the great collaboration with the authorship, lead to an interesting paper about Lgh reproduction and with promising perspectives in ecology and invasion ecology. References Dandelot S, Robles C, Pech N, Cazaubon A, Verlaque R (2008) Allelopathic potential of two invasive alien Ludwigia spp. Aquatic Botany, 88, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.004 Delbart E, Mahy G, Monty A (2013) Efficacité des méthodes de lutte contre le développement de cinq espèces de plantes invasives amphibies : Crassula helmsii, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Ludwigia grandiflora, Ludwigia peploides et Myriophyllum aquaticum (synthèse bibliographique). BASE, 17, 87–102. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=9586 Gérard J, Brion N, Triest L (2014) Effect of water column phosphorus reduction on competitive outcome and traits of Ludwigia grandiflora and L. peploides, invasive species in Europe. Aquatic Invasions, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.04 Glover R, Drenovsky RE, Futrell CJ, Grewell BJ (2015) Clonal integration in Ludwigia hexapetala under different light regimes. Aquatic Botany, 122, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.01.004 Hieda S, Kaneko Y, Nakagawa M, Noma N (2020) Ludwigia grandiflora (Michx.) Greuter & Burdet subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G. L. Nesom & Kartesz, an Invasive Aquatic Plant in Lake Biwa, the Largest Lake in Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica, 71, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.201911 Meisler J (2009) Controlling Ludwigia hexaplata in Northern California. Wetland Science and Practice, 26, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1672/055.026.0404 Portillo Lemus LO, Harang M, Bozec M, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2022) Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heteromorphic invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala. bioRxiv, 2021.07.15.452457, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457 Portillo Lemus LO, Bozec M, Harang M, Coudreuse J, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2021) Self-incompatibility limits sexual reproduction rather than environmental conditions in an invasive water primrose. Plant-Environment Interactions, 2, 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10042 Reid AJ, Carlson AK, Creed IF, Eliason EJ, Gell PA, Johnson PTJ, Kidd KA, MacCormack TJ, Olden JD, Ormerod SJ, Smol JP, Taylor WW, Tockner K, Vermaire JC, Dudgeon D, Cooke SJ (2019) Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews, 94, 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12480 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G (2013) A success story: water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 23, 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiébaut G (2013) Seasonal plasticity of Ludwigia grandiflora under light and water depth gradients: An outdoor mesocosm experiment. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 208, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.004 | Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala | Luis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding system influences local population genetic structure, effective size, offspring fitness and functional variation. Determining the respective importance of self- and cross-fertilization in hermaphroditic flo... |  | Biological invasions, Botany, Freshwater ecology, Pollination | Antoine Vernay | 2021-07-16 09:53:50 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle