When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation

Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques

https://doi.org/10.1101/307322

When the dispersal of the many outruns the dispersal of the few

Recommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

Are biological invasions driven by a few pioneers, running ahead of their conspecifics? Or are these pioneers constantly being caught up by, and folded into, the larger flux of propagules from the established populations behind them?

In ecology and beyond, these two scenarios are known as "pulled" and "pushed" fronts, and they come with different expectations. In a pushed front, invasion speed is not just a matter of how good individuals are at dispersing and settling new locations. It becomes a collective, density-dependent property of population fluxes. And in particular, it can depend on the equilibrium abundance of the established populations inside the range, i.e. the species’ carrying capacity K, factoring in its abiotic environment and biotic interactions.

This realization is especially important because it can flip around our expectations about which species expand fast, and how to manage them. We tend to think of initial colonization and long-term abundance as two independent axes of variation among species or indeed as two ends of a spectrum, in the classic competition-colonization tradeoff [1]. When both play into invasion speed, good dispersers might not outrun good competitors. This is useful knowledge, whether we want to contain an invasion or secure a reintroduction.

In their study "When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation", Haond et al [2] combine mathematical analysis, Individual-Based simulations and experiments to show that various mechanisms can cause pushed fronts, whose speed increases with the carrying capacity K of the species. Rather than focus on one particular angle, the authors endeavor to demonstrate that this qualitative effect appears again and again in a variety of settings.

It is perhaps surprising that this notable and general connection between K and invasion speed has managed to garner so little fame in ecology. A large fraction of the literature employs the venerable Fisher-KPP reaction-diffusion model, which combines local logistic growth with linear diffusion in space. This model has prompted both considerable mathematical developments [3] and many applications to modelling real invasions [4]. But it only allows pulled fronts, driven by the small populations at the edge of a species range, with a speed that depends only on their initial growth rate r.

This classic setup is, however, singular in many ways. Haond et al [2] use it as a null model, and introduce three mechanisms or factors that each ensure a role of K in invasion speed, while giving less importance to the pioneers at the border.

Two factors, the Allee effect and demographic stochasticity, make small edge populations slower to grow or less likely to survive. These two factors are studied theoretically, and to make their claims stronger, the authors stack the deck against K. When generalizing equations or simulations beyond the null case, it is easy to obtain functional forms where the parameter K does not only play the role of equilibrium carrying capacity, but also affects dynamical properties such as the maximum or mean growth rate. In that case, it can trivially change the propagation speed, without it meaning anything about the role of established populations behind the front. Haond et al [2] avoid this pitfall by disentangling these effects, at the cost of slightly more peculiar expressions, and show that varying essentially nothing but the carrying capacity can still impact the speed of the invasion front.

The third factor, density-dependent dispersal, makes small populations less prone to disperse. It is well established empirically and theoretically that various biological mechanisms, from collective organization to behavioral switches, can prompt organisms in denser populations to disperse more, e.g. in such a way as to escape competition [5]. The authors demonstrate how this effect induces a link between carrying capacity and invasion speed, both theoretically and in a dispersal experiment on the parasitoid wasp, Trichogramma chilonis.

Overall, this study carries a simple and clear message, supported by valuable contributions from different angles. Although some sections are clearly written for the theoretical ecology crowd, this article has something for everyone, from the stray physicist to the open-minded manager. The collaboration between theoreticians and experimentalists, while not central, is worthy of note. Because the narrative of this study is the variety of mechanisms that can lead to the same qualitative effect, the inclusion of various approaches is not a gimmick, but helps drive home its main message. The work is fairly self-contained, although one could always wish for further developments, especially in the direction of more quantitative testing of these mechanisms.

In conclusion, Haond et al [2] effectively convey the widely relevant message that, for some species, invading is not just about the destination, it is about the many offspring one makes along the way.

References

[1] Levins, R., & Culver, D. (1971). Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68(6), 1246–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246

[2] Haond, M., Morel-Journel, T., Lombaert, E., Vercken, E., Mailleret, L., & Roques, L. (2018). When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation. BioRxiv, 307322. doi: 10.1101/307322

[3] Crooks, E. C. M., Dancer, E. N., Hilhorst, D., Mimura, M., & Ninomiya, H. (2004). Spatial segregation limit of a competition-diffusion system with Dirichlet boundary conditions. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications, 5(4), 645–665. doi: 10.1016/j.nonrwa.2004.01.004

[4] Shigesada, N., & Kawasaki, K. (1997). Biological Invasions: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press, UK.

[5] Matthysen, E. (2005). Density-dependent dispersal in birds and mammals. Ecography, 28(3), 403–416. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2005.04073.x

| When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation | Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100004). Finding general patterns in the expansion of natural populations is a major challenge in ecology and invasion biology... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | Yuval Zelnik | 2018-04-25 10:18:48 | View |

Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal

Nathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat

https://doi.org/10.1101/442160

Are all the roads leading to Rome?

Recommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth and 1 anonymous reviewer

Identifying the factors which favour the establishment and spread of non-native species in novel environments is one of the keys to predict - and hence prevent or control - biological invasions. This includes biological factors (i.e. factors associated with the invasive species themselves), and one of the prevailing hypotheses is that some species traits may explain their impressive success to establish and spread in novel environments [1]. In animals, most research studies have focused on traits associated with fecundity, age at maturity, level of affiliation to humans or dispersal ability for instance. The “composite picture” of the perfect (i.e. successful) invader that has gradually emerged is a small-bodied animal strongly affiliated to human activities with high fecundity, high dispersal ability and a super high level of plasticity. Of course, the story is not that simple, and actually a perfect invader sometimes – if not often- takes another form… Carrying on to identify what makes a species a successful invader or not is hence still an important research axis with major implications.

In this manuscript, Charbonnel and collaborators [2] provide an interesting opportunity to gain novel insights into our understanding of (the) traits underlying invasion success. They nicely combine the power of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) with a clever comparative approach of two closely-related invasive rodents (the house mouse Mus musculus and the black rat Rattus rattus) in a common environment. They use this experimental design to test the appealing hypothesis that pathogens may be actors of the story, and may indirectly explain why some non-native species are so successful in invading novel habitats.

It is generally assumed that the community of pathogens encountered by non-native species in novel environments is different from that of their native area. On the one hand (the enemy-release hypothesis), it can be hypothesized that non-native species, when they arrive into a novel environment, will be relaxed from the pressure imposed by their native pathogens because local pathogens are not adapted (and hence do not infect) to this novel host. Because immune defence against pathogens is highly costly, non-native species establishing into a novel environment could hence reallocate these costs to other functions such as fecundity or dispersal apparatus. This scenario has been termed the “evolution of increased competitive ability” (EICA) hypothesis [3]. On the other hand (the EICA-refined hypothesis [4]), one can assume that invaders will encounter new pathogens in newly established areas, and will allocate energy toward cost-effective immune pathways to permit allocating a non-negligible amount of energy toward other functions. Finally, a last hypothesis (the “immune protection” hypothesis) assumes major changes in pathogen composition between native and invaded areas, which should lead to an overall increase in immune investment by the native species to successfully invade novel environments [4]. This last hypothesis suggests that only non-native species being able to take up the associated costs of immunity will be successful invaders.

The role of immunity in invasion success has yet been poorly investigated, mainly because of the difficulty to simultaneously analyse multiple immune pathways [4]. Charbonnel and collaborators [2] overpass this difficulty by screening all genes expressed (using a whole RNA sequencing approach) in an immune tissue: the spleen. They do so along the invasion routes of two sympatric invasive rodents in Africa and compare anciently and newly invaded areas (respectively). For one of the two species (the house mouse), they found a high number of immune-related genes to be up-regulated in newly invaded areas compared to anciently invaded areas. All categories of immune pathways (costly and cost-effective) were up-regulated, suggesting an overall increase in immune investment in the mouse, which corroborates the “immune protection” hypothesis. For the black rat, patterns of gene expression were somewhat different, with much less pronounced differentiation in gene expression between newly and anciently invaded areas. Among the few differentiated genes, a few were associated to immune responses and some of theses genes were even down-regulated in the newly invaded areas. This pattern may actually corroborate the EICA hypothesis, although it could alternatively suggest that stochastic processes (drift) associated to recent decrease in population size (which is expected during a colonisation event) are more important than selection imposed by pathogens in shaping patterns of immune gene expression.

Overall, this study [2] suggests (i) that immune-related traits are important in predicting invasion success and (ii) that two successful species with a similar invasion history and living in similar environments can use different life-history strategies to reach the same success. This later finding is particularly relevant and intriguing as it suggests that the traits and strategies deployed by species to colonise new habitats might actually be idiosyncratic, and that, if general trends actually emerge in regards of traits predicting the success of invaders, the devil might actually be into the details. Comparative studies are extremely important to identify the general rules and the specificities sustaining actual patterns, but these approaches are yet poorly used in biological invasions (at least empirically). The work presented by Charbonnel and colleagues [2] calls for future comparative studies performed at multiple spatial scales (native vs. non-native areas, anciently vs. recently invaded areas), multiple taxonomic resolutions and across multiple traits (to search for trade-offs), so that the success of invasive species can be properly understood and predicted.

References

[1] Jeschke, J. M., & Strayer, D. L. (2006). Determinants of vertebrate invasion success in Europe and North America. Global Change Biology, 12(9), 1608-1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01213.x

[2] Blossey, B., & Notzold, R. (1995). Evolution of increased competitive ability in invasive nonindigenous plants: a hypothesis. Journal of Ecology, 83(5), 887-889. doi: 10.2307/2261425

[3] Charbonnel, N., Galan, M., Tatard, C., Loiseau, A., Diagne, C. A., Dalecky, A., Parrinello, H., Rialle, S., Severac, D., & Brouat, C. (2019). Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal. bioRxiv, 442160, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/442160

[4] Lee, K. A., & Klasing, K. C. (2004). A role for immunology in invasion biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19(10), 523-529. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.012

| Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal | Nathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat | <p>Background: Biological invasions are major anthropogenic changes associated with threats to biodiversity and health. What determines the successful establishment of introduced populations still remains unsolved. Here we explore the appealing as... |  | Biological invasions, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Population ecology | Simon Blanchet | | 2018-10-14 12:21:52 | View |

Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa)

Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier

https://doi.org/10.1101/557066

Urban past predicts contemporary genetic structure in city rats

Recommended by Michelle DiLeo based on reviews by Torsti Schulz, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer

Urban areas are expanding worldwide, and have become a dominant part of the landscape for many species. Urbanization can fragment pre-existing populations of vulnerable species leading to population declines and the loss of connectivity. On the other hand, expansion of urban areas can also facilitate the spread of human commensals including pests. Knowledge of the features of cityscapes that facilitate gene flow and maintain diversity of pests is thus key to their management and eradication.

Cities are complex mosaics of natural and manmade surfaces, and habitat quality is not only influenced by physical aspects of the cityscape but also by socioeconomic factors and human behaviour. Constant development means that cities also change rapidly in time; contemporary urban life reflects only a snapshot of the environmental conditions faced by populations. It thus remains a challenge to identify the features that actually drive ecology and evolution of populations in cities [1]. While several studies have highlighted strong urban clines in genetic structure and adaption [2], few have considered the influence of factors beyond physical aspects of the cityscape or historical processes.

In this paper, Stragier et al. [3] sought to identify the current and past features of the cityscape and socioeconomic factors that shape genetic structure and diversity of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar, Senegal. The authors painstakingly digitized historical maps of Dakar from the time of European settlement in 1862 to present. The authors found that the main spatial genetic cline was best explained by historical cityscape features, with higher apparent gene flow and genetic diversity in areas that were connected earlier to initial European settlements. Beyond the main trend of spatial genetic structure, they found further evidence that current features of the cityscape were important. Specifically, areas with low vegetation and poor housing conditions were found to support large, genetically diverse populations. The authors demonstrate that their results are reproducible using several statistical approaches, including modeling that explicitly accounts for spatial autocorrelation.

The work of Stragier et al. [3] thus highlights that populations of city-dwelling species are the product of both past and present cityscapes. Going forward, urban evolutionary ecologists should consider that despite the potential for rapid evolution in urban landscapes, the signal of a species’ colonization can remain for generations.

References

[1] Rivkin, L. R., Santangelo, J. S., Alberti, M. et al. (2019). A roadmap for urban evolutionary ecology. Evolutionary Applications, 12(3), 384-398. doi: 10.1111/eva.12734

[2] Miles, L. S., Rivkin, L. R., Johnson, M. T., Munshi‐South, J. and Verrelli, B. C. (2019). Gene flow and genetic drift in urban environments. Molecular ecology, 28(18), 4138-4151. doi: 10.1111/mec.15221

[3] Stragier, C., Piry, S., Loiseau, A., Kane, M., Sow, A., Niang, Y., Diallo, M., Ndiaye, A., Gauthier, P., Borderon, M., Granjon, L., Brouat, C. and Berthier, K. (2020). Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa). bioRxiv, 557066, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/557066

| Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa) | Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier | <p>Population genetic approaches may be used to investigate dispersal patterns of species living in highly urbanized environment in order to improve management strategies for biodiversity conservation or pest control. However, in such environment,... |  | Biological invasions, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology | Michelle DiLeo | | 2019-02-22 08:36:13 | View |

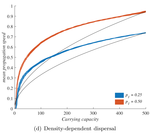

Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees

Clément Tourbez, Irène Semay, Apolline Michel, Denis Michez, Pascal Gerbaux, Antoine Gekière, Maryse Vanderplanck

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8192036

The importance of understanding bee nutrition

Recommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer

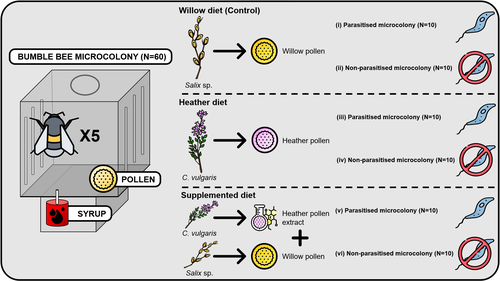

Contrasting with the great alarm on bee declines, it is astonishing how little basic biology we know about bees, including on abundant and widespread species that are becoming model species. Plant-pollinator relationships are one of the cornerstones of bee ecology, and researchers are increasingly documenting bees' diets. However, we rarely know which effects feeding on different flowers has on bees' health. This paper (Tourbez et al. 2023) uses an elegant experimental setting to test the effect of heather pollen on bumblebees' (Bombus terrestris) reproductive success. This is a timely question as heather is frequently used by bumblebees, and its nectar has been reported to reduce parasite infections. In fact, it has been suggested that bumblebees can medicate themselves when infected (Richardson et al. 2014), and the pollen of some Asteraceae has been shown to help them fight parasites (Gekière et al. 2022). The starting hypothesis is that heather pollen contains flavonoids that might have a similar effect. Unfortunately, Tourbez and collaborators do not support this hypothesis, showing a negative effect of heather pollen, in particular its flavonoids, in bumblebees offspring, and an increase in parasite loads when fed on flavonoids. This is important because it challenges the idea that many pollen and nectar chemical compounds might have a medicinal use, and force us to critically analyze the effect of chemical compounds in each particular case. The results open several questions, such as why bumblebees collect heather pollen, or in which concentrations or pollen mixes it is deleterious. A limitation of the study is that it uses micro-colonies, and extrapolating this to real-world conditions is always complex. Understanding bee declines require a holistic approach starting with bee physiology and scaling up to multispecies population dynamics.

References

Gekière, A., Semay, I., Gérard, M., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., & Vanderplanck, M. 2022. Poison or Potion: Effects of Sunflower Phenolamides on Bumble Bees and Their Gut Parasite. Biology, 11(4), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040545

Richardson, L.L., Adler, L.S., Leonard, A.S., Andicoechea, J., Regan, K.H., Anthony, W.E., Manson, J.S., & Irwin, R.E. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 282 (1803), 20142471. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2471

Tourbez, C., Semay, I., Michel, A., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., Gekière A. & Vanderplanck, M. 2023. Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees. Zenodo, ver 3, reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8192036

| Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees | Clément Tourbez, Irène Semay, Apolline Michel, Denis Michez, Pascal Gerbaux, Antoine Gekière, Maryse Vanderplanck | <p>There is evidence that specialised metabolites of flowering plants occur in both vegetative parts and floral resources (i.e., pollen and nectar), exposing pollinators to their biological activities. While such metabolites may be toxic to bees, ... |  | Botany, Chemical ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Pollination, Zoology | Ignasi Bartomeus | | 2023-04-10 21:22:34 | View |

Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical tree

Sébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret

https://doi.org/10.1101/351197

Growth trajectories, better than organ-level functional traits, reveal intraspecific response to environmental variation

Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz

Functional traits are “morpho-physio-phenological traits which impact fitness indirectly via their effects on growth, reproduction and survival” [1]. Most functional traits are defined at organ level, e.g. for leaves, roots and stems, and reflect key aspects of resource acquisition and resource use by organisms for their development and reproduction [2]. More rarely, some functional traits can be related to spatial development, such as vegetative height and lateral spread in plants.

Organ-level traits are especially popular because they can be measured in a standard way and easily compared over many plants. But these traits can broadly vary during the life of an organism. For instance, Roggy et al. [3] found that Leaf Mass Area can vary from 30 to 140 g.m^(-2) between seedling and adult stages for the canopy tree Dicorynia guianensis in French Guiana. Fortunel et al. [4] have also showed that developmental stages much contribute to functional trait variation within several Micropholis tree species in lowland Amazonia.

The way plants grow and invest resources into organs is variable during life and allows defining specific developmental sequences and architectural models [5,6]. There is clear ontogenic variation in leaf number, leaf properties and ramification patterns. Ontogenic variations reflect changing adaptation of an individual over its life, depending on the changing environmental conditions.

In this regard, measuring a single functional trait at organ level in adult trees should miss the variation of resource acquisition and use strategies over time. Thus we should built a more integrative approach of ecological development, also called “eco-devo” approach [7].

Although the ecological significance of ontogeny and developmental strategies is now well known, the extent to which it contributes to explain species survival and coexistence in communities is still broadly ignored in functional ecology. Levionnois et al. [8] investigated intraspecific variation of functional traits and growth trajectories in a typical, early-successional tree species in French Guiana, Amazonia. This species, Cecropia obtusa, is generalist regarding soil type and can be found on both white sand and ferralitic soil. The study examines whether there in intraspecific variation in functional traits and growth trajectories of C. obtusa in response to the contrasted soil types.

The tree communities observed on the two types of soils include species with distinctive functional trait values, that is, there are changes in species composition related to different species strategies along the classical wood and leaf economic spectra. The populations of C. obtusa found on the two soils showed some difference in functional traits, but it did not concern traits related to the main economic spectra. Conversely, the populations showed different growth strategies, in terms of spatial and temporal development.

The major lessons we can learn from the study are:

(i) Functional traits measured at organ level cannot reflect well how long-lived plants collect and invest resources during their life. The results show the potential of considering architectural and developmental traits together with organ-level functional traits, to better acknowledge the variation in ecological strategies over plant life, and thus to better understand community assembly processes.

(ii) What makes functional changes between communities differs when considering interspecific and intraspecific variation. Species turnover should encompass different corteges of soil specialists. These specialists are sorted along economic spectra, as shown in tropical rainforests and globally [2]. Conversely, a generalist species such as C. obtusa does occur on contrasted soil, which entails that it can accommodate the contrasted ecological conditions. However, the phenotypic adjustment is not related to how leaves and wood ensure photosynthesis, water and nutrient acquisition, but regards the way the resources are allocated to growth and reproduction over time.

The results of the study stress the need to better integrate growth strategies and ontogeny in the research agenda of functional ecology. We can anticipate that organ-level functional traits and growth trajectories will be more often considered together in ecological studies. The integration should help better understand the temporal niche of organisms, and how organisms can coexist in space and time with other organisms during their life. Recently, Klimešová et al. [9] have proposed standardized protocols for collecting plant modularity traits. Such effort to propose easy-to-measure traits representing plant development and ontogeny, with clear functional roles, should foster the awaited development of an “eco-devo” approach.

References

[1] Violle, C., Navas, M. L., Vile, D., Kazakou, E., Fortunel, C., Hummel, I., & Garnier, E. (2007). Let the concept of trait be functional!. Oikos, 116(5), 882-892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x

[2] Díaz, S. et al. (2016). The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature, 529(7585), 167-171. doi: 10.1038/nature16489

[3] Roggy, J. C., Nicolini, E., Imbert, P., Caraglio, Y., Bosc, A., & Heuret, P. (2005). Links between tree structure and functional leaf traits in the tropical forest tree Dicorynia guianensis Amshoff (Caesalpiniaceae). Annals of forest science, 62(6), 553-564. doi: 10.1051/forest:2005048

[4] Fortunel, C., Stahl, C., Heuret, P., Nicolini, E. & Baraloto, C. (2020). Disentangling the effects of environment and ontogeny on tree functional dimensions for congeneric species in tropical forests. New Phytologist. doi: 10.1111/nph.16393

[5] Barthélémy, D., & Caraglio, Y. (2007). Plant architecture: a dynamic, multilevel and comprehensive approach to plant form, structure and ontogeny. Annals of botany, 99(3), 375-407. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl260

[6] Hallé, F., & Oldeman, R. A. (1975). An essay on the architecture and dynamics of growth of tropical trees. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Universiti Malaya.

[7] Sultan, S. E. (2007). Development in context: the timely emergence of eco-devo. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(11), 575-582. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.06.014

[8] Levionnois, S., Tysklind, N., Nicolini, E., Ferry, B., Troispoux, V., Le Moguedec, G., Morel, H., Stahl, C., Coste, S., Caron, H. & Heuret, P. (2020). Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical tree. bioRxiv, 351197, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/351197

[9] Klimešová, J. et al. (2019). Handbook of standardized protocols for collecting plant modularity traits. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 40, 125485. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2019.125485

| Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical tree | Sébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret | <p style="text-align: justify;">1- Trait-environment relationships have been described at the community level across tree species. However, whether interspecific trait-environment relationships are consistent at the intraspecific level is yet unkn... |  | Botany, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Habitat selection, Ontogeny, Tropical ecology | François Munoz | | 2018-06-21 17:13:17 | View |

Does information theory inform chemical arms race communication?

Recommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Claudio Ramirez and 2 anonymous reviewers

One of the long-standing questions in evolutionary ecology is on the mechanisms involved in arms race coevolution. One way to address this question is to understand the conditions under which one species evolves traits in response to the presence of a second species and so on. However, specialized pairwise interactions are by far less common in nature than interactions involving a higher number of interacting species (Bascompte, Jordano 2013). While interactions between large sets of species are the norm rather than the exception in mutualistic (pollination, seed dispersal), and antagonist (herbivory, parasitism) relationships, few is known on the way species identify, process, and respond to information provided by other interacting species under field conditions (Schaefer, Ruxton 2011).

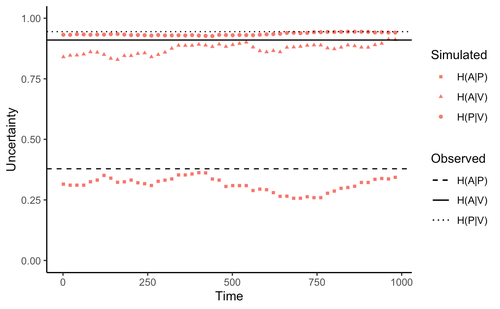

Zu et al. (2020) addressed this general question by developing an interesting information theory-based approach that hypothesized conditional entropy in chemical communication plays a role as proxy of fitness in plant-herbivore communities. More specifically, plant fitness was assumed to be related to the efficiency to code signals by plant species, and herbivore fitness to the capacity to decode plant signals. In this way, from the plant perspective, the elaboration of plant signals that elude decoding by herbivores is expected to be favored, as herbivores are expected to attack plants with simple chemical signals. The empirical observation upon which the model was tested was the redundancy in volatile organic compounds (VOC) found across plant species in a plant-herbivore community. Interestingly, Zu et al.’s model predicted successfully that VOC redundancy in the plant community associates with increased conditional entropy, which conveys herbivore confusion and plant protection against herbivory. In this way, plant species that evolve VOCs already present in the community might be benefitted, ultimately leading to the patterns of VOC redundancy commonly observed in nature.

Bass & Kessler performed a series of interesting observations on Zu et al. (2020), that can be organized along three lines of reasoning. First, from an evolutionary perspective, Bass & Kessler note the important point that accepting that conditional information entropy, estimated from the contribution of every plant species to volatile redundancy implies that average plant fitness seems to depend on community-level properties (i.e., what the other species in the community are doing) rather than on population-level characteristics (I.e., what the individuals belonging a population are doing). While the level at which selection acts upon is a longstanding debate (e.g., Goodnight, 1990; Williams, 1992), the model seems to contradict one of the basic tenets of Darwinian evolution. The extent to which this important observation invalidates the contribution of Zu et al. (2020) is open to scrutiny. However, one can indulge the evolutionary criticism by arguing that every theoretical model performs a number of assumptions to preserve the simplicity of analyses. Furthermore, even accepting the criticism, the overall information-based framework is valuable as it provides a fresh perspective to the way coding and decoding chemical information in plant-herbivore interactions may result in arm race coevolution. The question to be assessed by members of the scientific community is how strong the evolutionary assumptions are to be acceptable. A second line of reasoning involves consideration of additional routes of chemical information transfer. If chemical volatiles are involved in another ecological function unrelated to arm race (as they are) such as toxicity, crypsis, aposematism, etc., the conditional information indices considered as proxy to plant and herbivore fitness may be only secondarily related to arms race. This is an interesting observation, which suggests that VOC production may have more than one ecological function, as it often happens in “pleiotropic” traits (Strauss, Irwin 2004). This is an exciting avenue for future research. Finally, a third category of comments involves the relationship between conditional information entropy and plant and herbivore fitness. Bass & Kessler developed a Bayesian treatment of the community-level information developed by Zu et al. (2020) that permitted to estimate fitness on a species rather than community level. Their results revealed that community conditional entropies fail to align with species-level indices, suggesting that conclusions of Strauss & Irwin (2004) are not commensurate with fitness at the species level, where the analysis seems to be pertinent. In general, I strongly recommend Bass & Kessler’s contribution as it provides a series of observations and new perspectives to Zu et al. (2020). Rather than restricting their manuscript to blind criticisms, Bass & Kessler provides new interesting perspectives, which is always welcome as it improves the value and scope of the original work.

References

Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691131269.001.0001

Bass E, Kessler A (2022) Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities.” EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/xsbtm

Goodnight CJ (1990) Experimental Studies of Community Evolution I: The Response to Selection at the Community Level. Evolution, 44, 1614–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03850.x

Schaefer HM, Ruxton GD (2011) Plant-Animal Communication. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199563609.001.0001

Strauss SY, Irwin RE (2004) Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Multispecies Plant-Animal Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 435–466. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130215

Williams GC (1992) Natural Selection: Domains, Levels, and Challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York.

Zu P, Boege K, del-Val E, Schuman MC, Stevenson PC, Zaldivar-Riverón A, Saavedra S (2020) Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities. Science, 368, 1377–1381. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba2965

| Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities” | Ethan Bass, André Kessler | <p style="text-align: justify;">Zu et al (Science, 19 Jun 2020, p. 1377) propose that an ‘information arms-race’ between plants and herbivores explains plant-herbivore communication at the community level. However, the analysis presented here show... |  | Chemical ecology, Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Rodrigo Medel | | 2021-10-02 06:06:07 | View |

Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models

Virgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles

https://doi.org/10.1101/356469

Addressing uncertainty in Environmental Risk Assessment using mechanistic toxicological models coupled with Bayesian inference

Recommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Andreas Focks and 2 anonymous reviewers

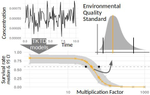

Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a strategic conceptual framework to characterize the nature and magnitude of risks, to humans and biodiversity, of the release of chemical contaminants in the environment. Several measures have been suggested to enhance the science and application of ERA, including the identification and acknowledgment of uncertainties that potentially influence the outcome of risk assessments, and the appropriate consideration of temporal scale and its linkage to assessment endpoints [1].

Baudrot & Charles [2] proposed to approach these questions by coupling toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models, which describe the time-course of processes leading to the adverse effects of a toxicant, with Bayesian inference. TKTD models separate processes influencing an organismal internal exposure (´toxicokinetics´, i.e., the uptake, bioaccumulation, distribution, biotransformation and elimination of a toxicant) from processes leading to adverse effects and ultimately its death (´toxicodynamics´) [3]. Although species and substance specific, the mechanistic nature of TKTD models facilitates the comparison of different toxicants, species, life stages, environmental conditions and endpoints [4].

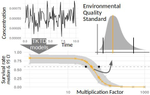

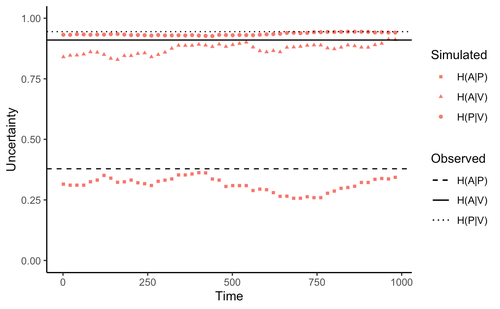

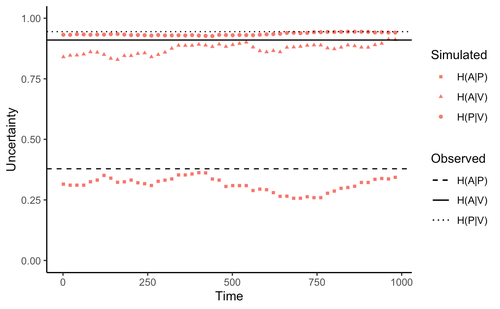

Baudrot & Charles [2] investigated the use of a Bayesian framework to assess the uncertainties surrounding the calibration of General Unified Threshold Models of Survival (a category of TKTD) with data from standard toxicity tests, and their propagation to predictions of regulatory toxicity endpoints such as LC(x,t) [the lethal concentration affecting any x% of the population at any given exposure duration of time t] and MF(x,t) [an exposure multiplication factor leading to any x% effect reduction due to the contaminant at any time t].

Once calibrated with empirical data, GUTS models were used to explore individual survival over time, and under untested exposure conditions. Lethal concentrations displayed a strong curvilinear decline with time of exposure. For a given total amount of contaminant, pulses separated by short time intervals yielded higher mortality than pulses separated by long time intervals, as did few pulses of high amplitude when compared to multiple pulses of low amplitude. The response to a pulsed contaminant exposure was strongly influenced by contaminant depuration times. These findings highlight one important contribution of TKTD modelling in ecotoxicology: they represent just a few of the hundreds of exposure scenarios that could be mathematically explored, and that would be unfeasible or even unethical to conduct experimentally.

GUTS models were also used for interpolations or extrapolations of assessment endpoints, and their marginal distributions. A case in point is the incipient lethal concentration. The responses of model organisms to contaminants in standard toxicity tests are typically assessed at fixed times of exposure (e.g. 24h or 48h in the Daphnia magna acute toxicity test). However, because lethal concentrations are strongly time-dependent, it has been suggested that a more meaningful endpoint would be the incipient (i.e. asymptotic) lethal concentration when time of exposure increases to infinity. The authors present a mathematical solution for calculating the marginal distribution of such incipient lethal concentration, thereby providing both more relevant information and a way of comparing experiments, compounds or species tested for different periods of time.

Uncertainties were found to change drastically with time of exposure, being maximal at extreme values of x for both LC(x,t) and MF(x,t). In practice this means that assessment endpoints estimated when the effects of the contaminant are weak (such as LC10, the contaminant concentration resulting in the mortality of 10% of the experimental population), a commonly used assessment value in ERA, are prone to be highly variable.

The authors end with recommendations for improved experimental design, including (i) using assessment endpoints at intermediate values of x (e.g., LC50 instead of LC10) (ii) prolonging exposure and recording mortality over the course of the experiment (iii) experimenting one or few peaks of high amplitude close to each other when assessing pulsed exposure. Whereas these recommendations are not that different from current practices, they are based on a more coherent mechanistic grounding.

Overall, this and other contributions from Charles, Baudrot and their research group contribute to turn TKTD models into a real tool for Environmental Risk Assessment. Further enhancement of ERA´s science and application could be achieved by extending the use of TKTD models to sublethal rather than lethal effects, and to chronic rather than acute exposure, as these are more controversial issues in decision-making regarding contaminated sites.

References

[1] Dale, V. H., Biddinger, G. R., Newman, M. C., Oris, J. T., Suter, G. W., Thompson, T., ... & Chapman, P. M. (2008). Enhancing the ecological risk assessment process. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 4(3), 306-313. doi: 10.1897/IEAM_2007-066.1

[2] Baudrot, V., & Charles, S. (2018). Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models. bioRxiv, 356469, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. doi: 10.1101/356469

[3] EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR), Ockleford, C., Adriaanse, P., Berny, P., Brock, T., Duquesne, S., ... & Kuhl, T. (2018). Scientific Opinion on the state of the art of Toxicokinetic/Toxicodynamic (TKTD) effect models for regulatory risk assessment of pesticides for aquatic organisms. EFSA Journal, 16(8), e05377. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5377

[4] Jager, T., Albert, C., Preuss, T. G., & Ashauer, R. (2011). General unified threshold model of survival-a toxicokinetic-toxicodynamic framework for ecotoxicology. Environmental science & technology, 45(7), 2529-2540. doi: 10.1021/es103092a

| Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models | Virgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles | <p>Providing reliable environmental quality standards (EQS) is a challenging issue for environmental risk assessment (ERA). These EQS are derived from toxicity endpoints estimated from dose-response models to identify and characterize the environm... |  | Chemical ecology, Ecotoxicology, Experimental ecology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | | 2018-06-27 21:33:30 | View |

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail

Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä

https://doi.org/10.1101/449777

Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snails

Recommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentis

Amongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor.

For all these reasons, experimental studies of the consequences of increased temperature hit some of a sweetspot and are a source of very nice research, in many different organisms. The work by Leicht and Seppala [5] complements a sequence of earlier studies by this group, using the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis as their model system [6-7].

In the present study, the authors investigate how a heat wave (a period of abnormally elevated temperature, here 25°C versus a normal 15°C) may have indirect effects on the next generation, through maternal effects. They question whether such indirect effects exist, and if they exist, how they compare, in terms of effect size, with the (more straightforward) direct effects observed in individuals that directly experience a heat wave. Transgenerational effects are well-known to occur following periods of physiological stress, and might thus have non negligible contributions to the overall effect of warming.

In this freshwater snail, heat has very strong direct effects: mortality increases at high temperature, but survivors grow much bigger, with a greater propensity to lay eggs and a (spectacular) three-fold increase in the number of eggs laid [6]. Considering that, it is easy to consider that transgenerational effects should be small game. And indeed, the present study also observes the big and obvious direct effects of elevated temperature: higher mortality, but greater propensity to oviposit. However, it was also found that the eggs were smaller if from mothers exposed to high temperature, with a correspondingly smaller size of hatchlings. This suggests that a heat wave causes the snails to lay more eggs, but smaller ones, reminiscent of a size-number trade-off. Unfortunately, clutch size could not be measured in this experiment, so this cannot be investigated any further. For this trait, the indirect effect may indeed be regarded as small game : eggs and hatchlings were about 15 % smaller, an effect size pretty small compared to the mammoth direct positive effect of temperature on shell length (see Figure 4 ; and also [6]). The same is true for developmental time (Figure 3).

However, for some traits the story was different. In particular, it was found that the (smaller) eggs produced from heated mothers were more likely to hatch by almost 10% (Figure 2). Here the indirect effect not only goes against the direct effect (hatching rate is lower at high temperature), but it also has similar effect size. As a consequence, taking into account both the indirect and direct effects, hatching success is essentially the same at 15°C and 25°C (Figure 2). Survival also had comparable effect sizes for direct and indirect effects. Indeed, survival was reduced by about 20% regardless of whom endured the heat stress (the focal individual or her mother; Figure 4). Interestingly, the direct and indirect effects were not quite cumulative: if a mother experienced a heat wave, heating up the offspring did not do much more damage, as though the offspring were ‘adapted’ to the warmer conditions (but keep in mind that, surprisingly, the authors’ stats did not find a significant interaction; Table 2).

At the end of the day, even though at first heat seems a relatively simple and understandable component of environmental change, this study shows how varied its effects can be effects on different components of individual fitness. The overall impact most likely is a mix of direct and indirect effects, of shifts along allocation trade-offs, and of maladaptive and adaptive responses, whose overall ecological significance is not so easy to grasp. That said, this study shows that direct and indirect (maternal) effects can sometimes go against one another and have similar intensities. Indirect effects should therefore not be overlooked in this kind of studies. It also gives a hint of what an interesting challenge it is to understand the adaptive or maladaptive nature of organism responses to elevated temperatures, and to evaluate their ultimate fitness consequences.

References

[1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704

[2] Adamo, S. A., & Lovett, M. M. E. (2011). Some like it hot: the effects of climate change on reproduction, immune function and disease resistance in the cricket Gryllus texensis. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 214(Pt 12), 1997–2004. doi: 10.1242/jeb.056531

[3] Deutsch, C. A., Tewksbury, J. J., Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D. S., Merrill, S. C., Huey, R. B., & Naylor, R. L. (2018). Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science (New York, N.Y.), 361(6405), 916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3466

[4] Sentis, A., Hemptinne, J.-L., & Brodeur, J. (2013). Effects of simulated heat waves on an experimental plant–herbivore–predator food chain. Global Change Biology, 19(3), 833–842. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12094

[5] Leicht, K., & Seppälä, O. (2019). Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail. BioRxiv, 449777, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/449777

[6] Leicht, K., Seppälä, K., & Seppälä, O. (2017). Potential for adaptation to climate change: family-level variation in fitness-related traits and their responses to heat waves in a snail population. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17(1), 140. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0988-x

[7] Leicht, K., Jokela, J., & Seppälä, O. (2013). An experimental heat wave changes immune defense and life history traits in a freshwater snail. Ecology and Evolution, 3(15), 4861–4871. doi: 10.1002/ece3.874

| Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail | Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä | <p>Global climate change imposes a serious threat to natural populations of many species. Estimates of the effects of climate change‐mediated environmental stresses are, however, often based only on their direct effects on organisms, and neglect t... |  | Climate change | vincent calcagno | | 2018-10-22 22:19:22 | View |

Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability

Arnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya

https://doi.org/10.1101/589895

On the importance of stoichiometric constraints for understanding global change effects on food web dynamics

Recommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The constraints associated with the mass balance of chemical elements (i.e. stoichiometric constraints) are critical to our understanding of ecological interactions, as outlined by the ecological stoichiometry theory [1]. Species in ecosystems differ in their elemental composition as well as in their level of elemental homeostasis [2], which can determine the outcome of interactions such as herbivory or decomposition on species coexistence and ecosystem functioning [3, 4].

Despite their importance, stoichiometric constraints are still often ignored in theoretical studies exploring the consequences of environmental perturbations on food web stability. Meanwhile, drivers of global change strongly alter biochemical cycles and the balance of chemical elements in ecosystems [5]. An important challenge is thus to understand how stoichiometric constraints affect food web responses to global changes.

The study of Sentis et al. [6] makes a step in that direction. This article investigates how stoichiometric constraints affect the response of consumer-resource dynamics to increasing temperature and nutrient inputs. It shows that the stoichiometric flexibility of the resource, coupled with lower consumer assimilation efficiency when stoichiometric unbalance between the resource and the consumer is higher, dampens the destabilizing effects of nutrient enrichment on species dynamics but reduces consumer persistence at extreme temperatures. Interestingly, these effects of stoichiometric constraints arise not only from changes in species assimilation efficiencies and carrying capacities but also from stoichiometric negative feedback loops on resource and consumer populations.

The results of this study are a call to further include stoichiometric constraints into food web models to better understand and predict the consequences of global changes on ecological communities. Many perspectives exist on that issue. For instance, it would be interesting to assess the effects of other stoichiometric mechanisms (e.g. changes in the element limiting growth [3]) on food web stability and its response to nutrient enrichment, as well as the effects of other global change drivers associated with altered biochemical cycles (e.g. carbon dioxide increase).

References

[1] Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J. (2017). Ecological Stoichiometry, The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. doi: 10.1515/9781400885695

[2] Elser, J. J., Sterner, R. W., Gorokhova, E., Fagan, W. F., Markow, T. A., Cotner, J. B., Harrison, J.F., Hobbie, S.E., Odell, G.M., Weider, L. W. (2000). Biological stoichiometry from genes to ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 3(6), 540–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2000.00185.x

[3] Daufresne, T., and Loreau, M. (2001). Plant–herbivore interactions and ecological stoichiometry: when do herbivores determine plant nutrient limitation? Ecology Letters, 4(3), 196–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00210.x

[4] Zou, K., Thébault, E., Lacroix, G., and Barot, S. (2016). Interactions between the green and brown food web determine ecosystem functioning. Functional Ecology, 30(8), 1454–1465. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12626

[5] Peñuelas, J., Poulter, B., Sardans, J., Ciais, P., van der Velde, M., Bopp, L., Boucher, O., Godderis, Y., Hinsinger, P., Llusia, J., Nardin, E., Vicca, S., Obersteiner, M., Janssens, I. A. (2013). Human-induced nitrogen–phosphorus imbalances alter natural and managed ecosystems across the globe. Nature Communications, 4(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3934

[6] Sentis, A., Haegeman, B. & Montoya, J.M. (2020). Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability. bioRxiv, 589895, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/589895

| Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability | Arnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya | <p>Temperature and nutrients are two of the most important drivers of global change. Both can modify the elemental composition (i.e. stoichiometry) of primary producers and consumers. Yet their combined effect on the stoichiometry, dynamics, and s... |  | Climate change, Community ecology, Food webs, Theoretical ecology, Thermal ecology | Elisa Thebault | | 2019-08-08 12:20:08 | View |

Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populations

Olivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier

https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.28.428563

Blue tits surviving in an ever-changing world

Recommended by Dieter Lukas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas

How long individuals live has a large influence on a number of biological processes, both for the individuals themselves as well as for the populations they live in. For a given species, survival is often summarized in curves showing the probability to survive from one age to the next. However, these curves often hide a large amount of variation in survival. Variation can occur from chance, or if individuals have different genotypes or phenotypes that can influence how long they might live, or if environmental conditions are not the same across time or space. Such spatiotemporal variations in the conditions that individuals experience can lead to complex patterns of evolution (Kokko et al. 2017) but because of the difficulties to obtain the relevant data they have not been studied much in natural populations.

In this manuscript, Bastianelli and colleagues (2021) identify which environmental and population conditions are associated with variation in annual survival of blue tits. The analyses are based on an impressive dataset, tracking a total of almost 5500 adults in four populations studied for at least 19 years. The authors describe two core results. First, average annual survival is lower in deciduous forests compared to evergreen forests. The differences in average annual survival between the forest types link with previously described differences, with individuals having larger clutches (Charmantier et al. 2016) and higher aggression (Dubuc-Messier et al. 2017) in the populations where adult survival is lower. Second, there are huge fluctuations from one year to the next in the percentage of individuals surviving which occur similarly in all populations. Even though survival covaried across the four populations, this variation was not associated with any of the local or global climate indices the authors investigated.

Studies like these are fundamental to our understanding of population change. They are important from an applied side as they can reveal the sustainability of populations and inform potential management options. On a basic research side, they reveal how evolution operates in populations. Theoretical studies predict that individuals are often not adapted to average conditions they experience, but either selected to balance the extremes they encounter or to make the best during harsh conditions when it really matters (Lewontin & Cohen 1969).

This study also opens the door to new research, highlighting that demographic studies should pay attention to variation in survival and other life history traits. For blue tits specifically, the study shows that in order to understand the demography of populations we need a better mechanistic understanding of the environmental and physiological pressures influencing whether individuals die or not to make predictions whether and how climate or other ecological effects shape variation in survival.

References

Bastianelli O, Robert A, Doutrelant C, Franceschi C de, Giovannini P, Charmantier A (2021) Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populations. bioRxiv, 2021.01.28.428563, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.28.428563

Charmantier A, Doutrelant C, Dubuc-Messier G, Fargevieille A, Szulkin M (2016) Mediterranean blue tits as a case study of local adaptation. Evolutionary Applications, 9, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12282

Dubuc-Messier G, Réale D, Perret P, Charmantier A (2017) Environmental heterogeneity and population differences in blue tits personality traits. Behavioral Ecology, 28, 448–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arw148

Kokko H, Chaturvedi A, Croll D, Fischer MC, Guillaume F, Karrenberg S, Kerr B, Rolshausen G, Stapley J (2017) Can Evolution Supply What Ecology Demands? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.12.005

Lewontin RC, Cohen D (1969) On Population Growth in a Randomly Varying Environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 62, 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.62.4.1056

| Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populations | Olivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">In a context of rapid climate change, the influence of large-scale and local climate on population demography is increasingly scrutinized, yet studies are usually focused on one population. Demographic parameters, i... |  | Climate change, Demography, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Population ecology | Dieter Lukas | | 2021-01-29 15:24:23 | View |

based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz

based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz

based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas

based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas