Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Jan 2023

Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic driversOmar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739Alpine ecology and their dynamics under climate changeRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewerResearch about the effects of climate change on ecological communities has been abundant in the last decades. In particular, studies about the effects of climate change on mountain ecosystems have been key for understanding and communicating the consequences of this global phenomenon. Alpine regions show higher increases in warming in comparison to low-altitude ecosystems and this trend is likely to continue. This warming has caused reduced snowfall and/or changes in the duration of snow cover. For example, Notarnicola (2020) reported that 78% of the world’s mountain areas have experienced a snow cover decline since 2000. In the same vein, snow cover has decreased by 10% compared with snow coverage in the late 1960s (Walther et al., 2002) and snow cover duration has decreased at a rate of 5 days/decade (Choi et al., 2010). These changes have impacted the dynamics of high-altitude plant and animal populations. Some impacts are changes in the hibernation of animals, the length of the growing season for plants and the soil microbial composition (Chávez et al. 2021). Lenzi et al. (2023), give us an excellent study using long-term data on alpine amphibian populations. Authors show how climate change has impacted the reproductive phenology of Bufo bufo, especially the breeding season starts 30 days earlier than ~40 years ago. This earlier breeding is associated with the increasing temperatures and reduced snow cover in these alpine ecosystems. However, these changes did not occur in a linear trend but a marked acceleration was observed until mid-1990s with a later stabilization. Authors associated these nonlinear changes with complex interactions between the global trend of seasonal temperatures and site-specific conditions. Beyond the earlier breeding season, changes in phenology can have important impacts on the long-term viability of alpine populations. Complex interactions could involve positive and negative effects like harder environmental conditions for propagules, faster development of juveniles, or changes in predation pressure. This study opens new research opportunities and questions like the urgent assessment of the global impact of climate change on animal fitness. This study provides key information for the conservation of these populations. References Chávez RO, Briceño VF, Lastra JA, Harris-Pascal D, Estay SA (2021) Snow Cover and Snow Persistence Changes in the Mocho-Choshuenco Volcano (Southern Chile) Derived From 35 Years of Landsat Satellite Images. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.643850 Choi G, Robinson DA, Kang S (2010) Changing Northern Hemisphere Snow Seasons. Journal of Climate, 23, 5305–5310. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3644.1 Lenzi O, Grossenbacher K, Zumbach S, Lüscher B, Althaus S, Schmocker D, Recher H, Thoma M, Ozgul A, Schmidt BR (2022) Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers.bioRxiv, 2022.08.16.503739, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739 Notarnicola C (2020) Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sensing of Environment, 243, 111781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111781 | Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers | Omar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt | <p style="text-align: justify;">Strong phenological shifts in response to changes in climatic conditions have been reported for many species, including amphibians, which are expected to breed earlier. Phenological shifts in breeding are observed i... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Zoology | Sergio Estay | Anonymous, Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-18 08:25:21 | View |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

27 Apr 2021

Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit fliesBenoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326Understanding the interplay between host-specificity, environmental conditions and competition through the sound application of Joint Species Distribution ModelsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann

Understanding why and how species coexist in local communities is one of the central questions in ecology. There is general agreement that species distribution and coexistence are determined by a number of key mechanisms, including the environmental requirements of species, dispersal, evolutionary constraints, resource availability and selection, metapopulation dynamics, and biotic interactions (e.g. Soberón & Nakamura 2009; Colwell & Rangel 2009; Ricklefs 2015). These factors are however intricately intertwined in a scale-structured fashion (Hortal et al. 2010; D’Amen et al. 2017), making it particularly difficult to tease apart the effects of each one of them. This could be addressed by the novel field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling (JSDM; Okasvainen & Abrego 2020), as it allows assessing the effects of several sets of factors and the co-occurrence and/or covariation in abundances of potentially interacting species at the same time (Pollock et al. 2014; Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Dormann et al. 2018). However, the development of JSDM has been hampered by the general lack of good-quality detailed data on species co-occurrences and abundances (see Hortal et al. 2015). Facon et al. (2021) use a particularly large compilation of field surveys to study the abundance and co-occurrence of Tephritidae fruit flies in c. 400 orchards, gardens and natural areas throughout the island of Réunion. Further, they combine such information with lab data on their host-selection fundamental niche (i.e. in the absence of competitors), codifying traits of female choice and larval performances in 21 host species. They use Poisson Log-Normal models, a type of mixed model that allows one to jointly model the random effects associated with all species, and retrieve the covariations in abundance that are not explained by environmental conditions or differences in sampling effort. Then, they use a series of models to evaluate the effects on these matrices of ecological covariates (date, elevation, habitat, climate and host plant), species interactions (by comparing with a constrained residual variance-covariance matrix) and the species’ host-selection fundamental niches (through separate models for each fly species). The eight Tephritidae species inhabiting Réunion include both generalists and specialists in Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae with a known history of interspecific competition. Facon et al. (2021) use a comprehensive JSDM approach to assess the effects of different factors separately and altogether. This allows them to identify large effects of plant hosts and the fundamental host-selection niche on species co-occurrence, but also to show that ecological covariates and weak –though not negligible– species interactions are necessary to account for all residual variance in the matrix of joint species abundances per site. Further, they also find evidence that the fitness per host measured in the lab has a strong influence on the abundances in each host plant in the field for specialist species, but not for generalists. Indeed, the stronger effects of competitive exclusion were found in pairs of Cucurbitaceae specialist species. However, these analyses fail to provide solid grounds to assess why generalists are rarely found in Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae. Although they argue that this may be due to Connell’s (1980) ghost of competition past (past competition that led to current niche differentiation), further data on the evolutionary history of these fruit flies is needed to assess this hypothesis. Finding evidence for the effects of competitive interactions on species’ occurrences and spatial distributions is often difficult, perhaps because these effects occur over longer time scales than the ones usually studied by ecologists (Yackulic 2017). The work by Facon and colleagues shows that weak effects of competition can be detected also at the short ecological timescales that determine coexistence in local communities, under the virtuous combination of good-quality data and sound analytical designs that account for several aspects of species’ niches, their biotopes and their joint population responses. This adds a new dimension to the application of Hutchinson’s (1978) niche framework to understand the spatial dynamics of species and communities (see also Colwell & Rangel 2009), although further advances to incorporate dispersal-driven metacommunity dynamics (see, e.g., Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Leibold et al. 2017) are certainly needed. Nonetheless, this work shows the potential value of in-depth analyses of species coexistence based on combining good-quality field data with well-thought out JSDM applications. If many studies like this are conducted, it is likely that the uprising field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling will improve our understanding of the hierarchical relationships between the different factors affecting species coexistence in ecological communities in the near future.

References Colwell RK, Rangel TF (2009) Hutchinson’s duality: The once and future niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19651–19658. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901650106 Connell JH (1980) Diversity and the Coevolution of Competitors, or the Ghost of Competition Past. Oikos, 35, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 D’Amen M, Rahbek C, Zimmermann NE, Guisan A (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Dormann CF, Bobrowski M, Dehling DM, Harris DJ, Hartig F, Lischke H, Moretti MD, Pagel J, Pinkert S, Schleuning M, Schmidt SI, Sheppard CS, Steinbauer MJ, Zeuss D, Kraan C (2018) Biotic interactions in species distribution modelling: 10 questions to guide interpretation and avoid false conclusions. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27, 1004–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759 Facon B, Hafsi A, Masselière MC de la, Robin S, Massol F, Dubart M, Chiquet J, Frago E, Chiroleu F, Duyck P-F, Ravigné V (2021) Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of community structure in fruit flies. bioRxiv, 2020.12.07.414326. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326 Hortal J, de Bello F, Diniz-Filho JAF, Lewinsohn TM, Lobo JM, Ladle RJ (2015) Seven Shortfalls that Beset Large-Scale Knowledge of Biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46, 523–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054400 Hortal J, Roura‐Pascual N, Sanders NJ, Rahbek C (2010) Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 33, 51–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06428.x Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Leibold MA, Chase JM, Ernest SKM (2017) Community assembly and the functioning of ecosystems: how metacommunity processes alter ecosystems attributes. Ecology, 98, 909–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1697 Ovaskainen O, Abrego N (2020) Joint Species Distribution Modelling: With Applications in R. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108591720 Ovaskainen O, Roy DB, Fox R, Anderson BJ (2016) Uncovering hidden spatial structure in species communities with spatially explicit joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12502 Pollock LJ, Tingley R, Morris WK, Golding N, O’Hara RB, Parris KM, Vesk PA, McCarthy MA (2014) Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180 Ricklefs RE (2015) Intrinsic dynamics of the regional community. Ecology Letters, 18, 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12431 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Yackulic CB (2017) Competitive exclusion over broad spatial extents is a slow process: evidence and implications for species distribution modeling. Ecography, 40, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02836 | Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit flies | Benoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné | <p style="text-align: justify;">The relative importance of ecological factors and species interactions for phytophagous insect species distributions has long been a controversial issue. Using field abundances of eight sympatric Tephritid fruit fli... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | Carsten Dormann, Joaquín Calatayud | 2020-12-08 06:44:25 | View |

02 Jan 2024

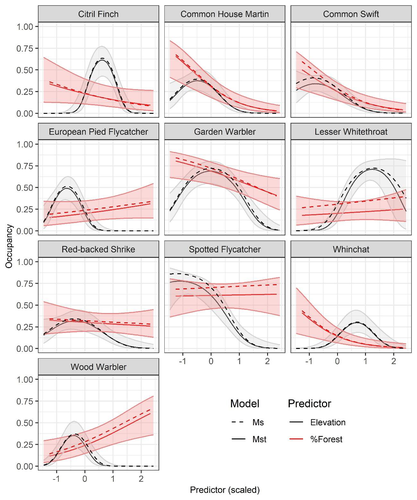

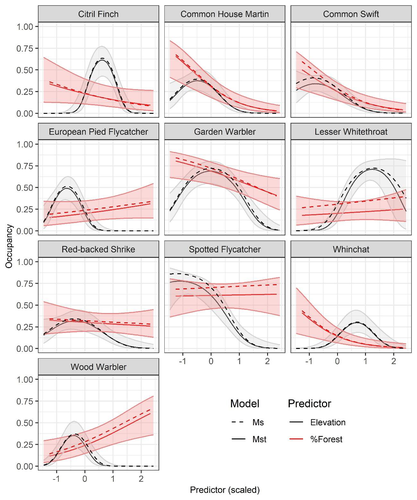

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

12 Aug 2021

A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm callSamantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5Does the active vocabulary in Great-tailed Grackles supports their range expansion? New study will find outRecommended by Jan Oliver Engler based on reviews by Guillermo Fandos and 2 anonymous reviewersAlarm calls are an important acoustic signal that can decide the life or death of an individual. Many birds are able to vary their alarm calls to provide more accurate information on e.g. urgency or even the type of a threatening predator. According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis, the habitat plays an important role too in how acoustic patterns get transmitted. This is of particular interest for range-expanding species that will face new environmental conditions along the leading edge. One could hypothesize that the alarm call repertoire of a species could increase in newly founded ranges to incorporate new habitats and threats individuals might face. Hence selection for a larger active vocabulary might be beneficial for new colonizers. Using the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a model species, Samantha Bowser from Arizona State University and Maggie MacPherson from Louisiana State University want to find out exactly that. The Great-Tailed Grackle is an appropriate species given its high vocal diversity. Also, the species consists of different subspecies that show range expansions along the northern range edge yet to a varying degree. Using vocal experiments and field recordings the researchers have a high potential to understand more about the acoustic adaptation hypothesis within a range dynamic process. Over the course of this assessment, the authors incorporated the comments made by two reviewers into a strong revision of their research plans. With that being said, the few additional comments made by one of the initial reviewers round up the current stage this interesting research project is in. To this end, I can only fully recommend the revised research plan and am much looking forward to the outcomes from the author’s experiments, modeling, and field data. With the suggestions being made at such an early stage I firmly believe that the final outcome will be highly interesting not only to an ornithological readership but to every ecologist and biogeographer interested in drivers of range dynamic processes. References Bowser, S., MacPherson, M. (2021). A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call. In principle recommendation by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5. Version 3 | A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call | Samantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson | <p>The acoustic adaptation hypothesis posits that animal sounds are influenced by the habitat properties that shape acoustic constraints (Ey and Fischer 2009, Morton 2015, Sueur and Farina 2015).Alarm calls are expected to signal important habitat... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Coexistence, Dispersal & Migration, Habitat selection, Landscape ecology | Jan Oliver Engler | Darius Stiels, Anonymous | 2020-12-01 18:11:02 | View |

12 Mar 2023

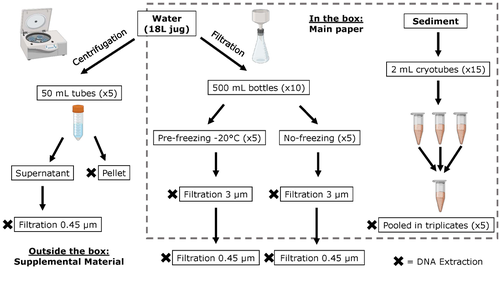

Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities.Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388Processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters from coastal lagoonsRecommended by Claudia Piccini based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Rutger De WitCoastal lagoons are among the most productive natural ecosystems on Earth. These relatively closed basins are important habitats and nursery for endemic and endangered species and are extremely vulnerable to nutrient input from the surrounding catchment; therefore, they are highly susceptible to anthropogenic influence, pollution and invasion (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). In general, coastal lagoons exhibit great spatial and temporal variability in their physicochemical water characteristics due to the sporadic mixing of freshwater with marine influx. One of the alternatives for monitoring communities or target species in aquatic ecosystems is the environmental DNA (eDNA), since overcomes some limitations from traditional methods and enables the investigation of multiple species from a single sample (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). In coastal lagoons, where the water turbidity is highly variable, there is a major challenge for monitoring the eDNA because filtering turbid water to obtain the eDNA is problematic (filters get rapidly clogged, there is organic and inorganic matter accumulation, etc.). The study by Turba et al. (2023) analyzes different ways of dealing with eDNA sampling and processing in turbid waters and sediments of coastal lagoons, and offers guidelines to obtain unbiased results from the subsequent sequencing using 12S (fish) and 16S (Bacteria and Archaea) universal primers. They analyzed the effect on taxa detection of: i) freezing or not prior to filtering; ii) freezing prior to centrifugation to obtain a sample pellet; and iii) using frozen sediment samples as a proxy of what happens in the water. The authors propose these different alternatives (freeze, do not freeze, sediment sampling) because they consider that they are the easiest to carry out. They found that freezing before filtering using a 3 µm pore size filter had no effects on community composition for either primer, and therefore it is a worthwhile approach for comparison of fish, bacteria and archaea in this kind of system. However, significantly different bacterial community composition was found for sediment compared to water samples. Also, in sediment samples the replicates showed to be more heterogeneous, so the authors suggest increasing the number of replicates when using sediment samples. Something that could be a concern with the study is that the rarefaction curves based on sequencing effort for each protocol did not saturate in any case, this being especially evident in sediment samples. The authors were aware of this, used the slopes obtained from each curve as a measure of comparison between samples and considering that the sequencing depth did not meet their expectations, they managed to achieve their goal and to determine which protocol is the most promising for eDNA monitoring in coastal lagoons. Although there are details that could be adjusted in relation to this item, I consider that the approach is promising for this type of turbid system. References Pérez-Ruzafa A, Campillo S, Fernández-Palacios JM, García-Lacunza A, García-Oliva M, Ibañez H, Navarro-Martínez PC, Pérez-Marcos M, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Quispe-Becerra JI, Sala-Mirete A, Sánchez O, Marcos C (2019) Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00026 Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 Turba R, Thai GH, Jacobs DK (2023) Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.495388, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388 | Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. | Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are an important habitat for endemic and threatened species in California that have suffered impacts from urbanization and increased drought. Environmental DNA has been promoted as a way to aid in th... |  | Biodiversity, Community genetics, Conservation biology, Freshwater ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Claudia Piccini | David Murray-Stoker | 2022-06-20 20:31:51 | View |

20 Jun 2019

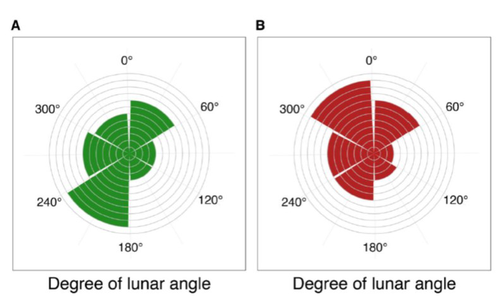

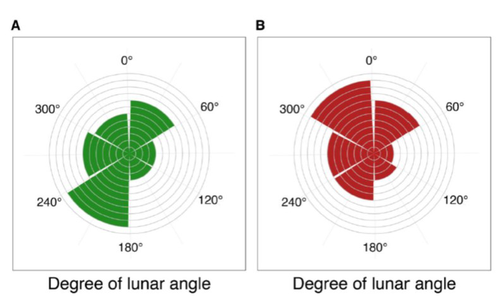

Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predatorChristophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel https://doi.org/10.1101/472431Sexual segregation in a sexually dimorphic seabird: a matter of spatial scaleRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by Dries Bonte and 1 anonymous reviewerSexual segregation appears in many taxa and can have important ecological, evolutionary and conservation implications. Sexual segregation can take two forms: either the two sexes specialise in different habitats but share the same area (habitat segregation), or they occupy the same habitat but form separate, unisex groups (social segregation) [1,2]. Segregation would have evolved as a way to avoid, or at least, reduce intersexual competition. References [1] Conradt, L. (2005). Definitions, hypotheses, models and measures in the study of animal segregation. In Sexual segregation in vertebrates: ecology of the two sexes (Ruckstuhl K.E. and Neuhaus, P. eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Pp:11–34. | Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predator | Christophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel | <p>Sexual segregation is common in many species and has been attributed to intra-specific competition, sex-specific differences in foraging efficiency or in activity budgets and habitat choice. However, very few studies have simultaneously quantif... |  | Foraging, Marine ecology | Denis Réale | Dries Bonte, Anonymous | 2018-11-19 13:40:59 | View |

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

22 Nov 2021

When more competitors means less harvested resourceRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Francois Massol, Jeremy Van Cleve and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois Massol, Jeremy Van Cleve and 1 anonymous reviewer

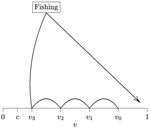

In this paper, Alan R. Rogers (2021) examines the dynamics of foraging strategies for a resource that gains value over time (e.g., ripening fruits), while there is a fixed cost of attempting to forage the resource, and once the resource is harvested nothing is left for other harvesters. For this model, not any pure foraging strategy is evolutionary stable. A mixed equilibrium exists, i.e., with a mixture of foraging strategies within the population, which is still evolutionarily unstable. Nonetheless, Alan R. Rogers shows that for a large number of competitors and/or high harvesting cost, the mixture of strategies remains close to the mixed equilibrium when simulating the dynamics. Surprisingly, in a large population individuals will less often attempt to forage the resource and will instead “go fishing”. The paper also exposes an experiment of the game with students, which resulted in a strategy distribution somehow close to the theoretical mixture of strategies. The economist John F. Nash Jr. (1950) gained the Nobel Prize of economy in 1994 for his game theoretical contributions. He gave his name to the “Nash equilibrium”, which represents a set of individual strategies that is reached whenever all the players have nothing to gain by changing their strategy while the strategies of others are unchanged. Alan R. Rogers shows that the mixed equilibrium in the foraging game is such a Nash equilibrium. Yet it is evolutionarily unstable insofar as a distribution close to the equilibrium can invade. The insights of the study are twofold. First, it sheds light on the significance of Nash equilibrium in an ecological context of foraging strategies. Second, it shows that an evolutionarily unstable state can rule the composition of the ecological system. Therefore, the contribution made by the paper should be most significant to better understand the dynamics of competitive communities and their eco-evolutionary trajectories. References Nash JF (1950) Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 36, 48–49. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.36.1.48 Rogers AR (2021) Beating your Neighbor to the Berry Patch. bioRxiv, 2020.11.12.380311, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.12.380311

| Beating your neighbor to the berry patch | Alan R. Rogers | <p style="text-align: justify;">Foragers often compete for resources that ripen (or otherwise improve) gradually. What strategy is optimal in this situation? It turns out that there is no optimal strategy. There is no evolutionarily stable strateg... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Foraging | François Munoz | Erol Akçay, Jorge Peña, Sébastien Lion, François Rousset, Ulf Dieckmann , Troy Day , Corina Tarnita , Florence Debarre , Daniel Friedman , Vlastimil Krivan , Ulf Dieckmann | 2020-12-10 18:38:49 | View |

31 Aug 2023

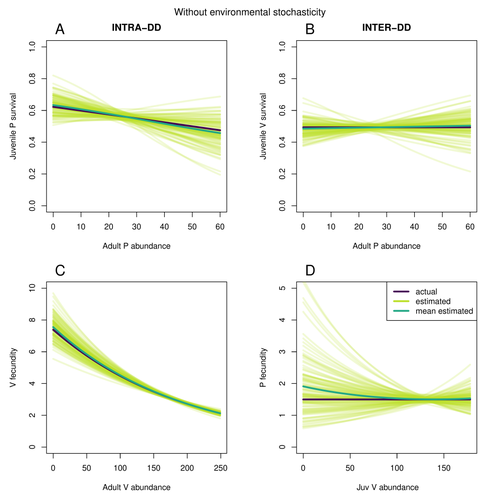

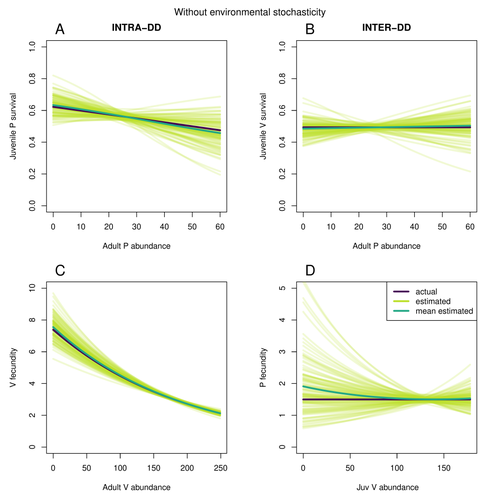

Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey modelsMatthieu Paquet, Frederic Barraquand https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7WAddressing the daunting challenge of estimating species interactions from count dataRecommended by Tim Coulson and David Alonso and David Alonso based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Trophic interactions are at the heart of community ecology. Herbivores consume plants, predators consume herbivores, and pathogens and parasites infect, and sometimes kill, individuals of all species in a food web. Given the ubiquity of trophic interactions, it is no surprise that ecologists and evolutionary biologists strive to accurately characterize them. The outcome of an interaction between individuals of different species depends upon numerous factors such as the age, sex, and even phenotype of the individuals involved and the environment in which they are in. Despite this complexity, biologists often simplify an interaction down to a single number, an interaction coefficient that describes the average outcome of interactions between members of the populations of the species. Models of interacting species tend to be very simple, and interaction coefficients are often estimated from time series of population sizes of interacting species. Although biologists have long known that this approach is often approximate and sometimes unsatisfactory, work on estimating interaction strengths in more complex scenarios, and using ecological data beyond estimates of abundance, is still in its infancy. In their paper, Matthieu Paquet and Frederic Barraquand (2023) develop a demographic model of a predator and its prey. They then simulate demographic datasets that are typical of those collected by ecologists and use integrated population modelling to explore whether they can accurately retrieve the values interaction coefficients included in their model. They show that they can with good precision and accuracy. The work takes an important step in showing that accurate interaction coefficients can be estimated from the types of individual-based data that field biologists routinely collect, and it paves for future work in this area. As if often the case with exciting papers such as this, the work opens up a number of other avenues for future research. What happens as we move from demographic models of two species interacting such as those used by Paquet and Barraquand to more realistic scenarios including multiple species? How robust is the approach to incorrectly specified process or observation models, core components of integrated population modelling that require detailed knowledge of the system under study? Integrated population models have become a powerful and widely used tool in single-species population ecology. It is high time the techniques are extended to community ecology, and this work takes an important step in showing that this should and can be done. I would hope the paper is widely read and cited. References Paquet, M., & Barraquand, F. (2023). Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7W | Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models | Matthieu Paquet, Frederic Barraquand | <p style="text-align: justify;">Inferring the strength of species interactions from demographic data is a challenging task. The Integrated Population Modelling (IPM) approach, bringing together population counts, capture-recapture, and individual-... |  | Community ecology, Demography, Euring Conference, Food webs, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Tim Coulson | Ilhan Özgen-Xian | 2023-01-05 17:02:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle