Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Mar 2020

The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategiesCharlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux https://doi.org/10.1101/790634The importance of spatio-temporal dynamics on MPA's designRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Ana S. L. Rodrigues and 1 anonymous reviewerMarine protected areas (MPA) have arisen as the main approach for conservation of marine species. Fishes, marine mammals and birds can be conservation targets that justify the implementation of these areas. However, MPAs undergo many of the problems faced by their terrestrial equivalent. One of the major concerns is that these conservation areas are spatially constrained, by logistic reasons, and many times these constraints caused that key areas for the species (reproductive sites, refugees, migration) fall outside the limits, making conservation efforts even more difficult. Lambert et al. [1] evaluate at what point the Bay of Biscay MPA contains key ecological areas for several emblematic species. The evaluation incorporated a spatio-temporal dimension. To evaluate these ideas, authors evaluate two population descriptors: aggregation and persistence of several species of cetaceans and seabirds. References [1] Lambert, C., Dorémus, G. and V. Ridoux (2020) The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies. bioRxiv, 790634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/790634 | The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies | Charlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux | <p>The main type of zonal conservation approaches corresponds to Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are spatially defined and generally static entities aiming at the protection of some target populations by the implementation of a management pla... |  | Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Species distributions | Sergio Estay | 2019-10-03 08:47:17 | View | |

24 Jan 2023

Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic driversOmar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739Alpine ecology and their dynamics under climate changeRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewerResearch about the effects of climate change on ecological communities has been abundant in the last decades. In particular, studies about the effects of climate change on mountain ecosystems have been key for understanding and communicating the consequences of this global phenomenon. Alpine regions show higher increases in warming in comparison to low-altitude ecosystems and this trend is likely to continue. This warming has caused reduced snowfall and/or changes in the duration of snow cover. For example, Notarnicola (2020) reported that 78% of the world’s mountain areas have experienced a snow cover decline since 2000. In the same vein, snow cover has decreased by 10% compared with snow coverage in the late 1960s (Walther et al., 2002) and snow cover duration has decreased at a rate of 5 days/decade (Choi et al., 2010). These changes have impacted the dynamics of high-altitude plant and animal populations. Some impacts are changes in the hibernation of animals, the length of the growing season for plants and the soil microbial composition (Chávez et al. 2021). Lenzi et al. (2023), give us an excellent study using long-term data on alpine amphibian populations. Authors show how climate change has impacted the reproductive phenology of Bufo bufo, especially the breeding season starts 30 days earlier than ~40 years ago. This earlier breeding is associated with the increasing temperatures and reduced snow cover in these alpine ecosystems. However, these changes did not occur in a linear trend but a marked acceleration was observed until mid-1990s with a later stabilization. Authors associated these nonlinear changes with complex interactions between the global trend of seasonal temperatures and site-specific conditions. Beyond the earlier breeding season, changes in phenology can have important impacts on the long-term viability of alpine populations. Complex interactions could involve positive and negative effects like harder environmental conditions for propagules, faster development of juveniles, or changes in predation pressure. This study opens new research opportunities and questions like the urgent assessment of the global impact of climate change on animal fitness. This study provides key information for the conservation of these populations. References Chávez RO, Briceño VF, Lastra JA, Harris-Pascal D, Estay SA (2021) Snow Cover and Snow Persistence Changes in the Mocho-Choshuenco Volcano (Southern Chile) Derived From 35 Years of Landsat Satellite Images. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.643850 Choi G, Robinson DA, Kang S (2010) Changing Northern Hemisphere Snow Seasons. Journal of Climate, 23, 5305–5310. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3644.1 Lenzi O, Grossenbacher K, Zumbach S, Lüscher B, Althaus S, Schmocker D, Recher H, Thoma M, Ozgul A, Schmidt BR (2022) Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers.bioRxiv, 2022.08.16.503739, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739 Notarnicola C (2020) Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sensing of Environment, 243, 111781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111781 | Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers | Omar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt | <p style="text-align: justify;">Strong phenological shifts in response to changes in climatic conditions have been reported for many species, including amphibians, which are expected to breed earlier. Phenological shifts in breeding are observed i... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Zoology | Sergio Estay | Anonymous, Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-18 08:25:21 | View |

20 Feb 2019

Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in SenegalNathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat https://doi.org/10.1101/442160Are all the roads leading to Rome?Recommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth and 1 anonymous reviewerIdentifying the factors which favour the establishment and spread of non-native species in novel environments is one of the keys to predict - and hence prevent or control - biological invasions. This includes biological factors (i.e. factors associated with the invasive species themselves), and one of the prevailing hypotheses is that some species traits may explain their impressive success to establish and spread in novel environments [1]. In animals, most research studies have focused on traits associated with fecundity, age at maturity, level of affiliation to humans or dispersal ability for instance. The “composite picture” of the perfect (i.e. successful) invader that has gradually emerged is a small-bodied animal strongly affiliated to human activities with high fecundity, high dispersal ability and a super high level of plasticity. Of course, the story is not that simple, and actually a perfect invader sometimes – if not often- takes another form… Carrying on to identify what makes a species a successful invader or not is hence still an important research axis with major implications. References [1] Jeschke, J. M., & Strayer, D. L. (2006). Determinants of vertebrate invasion success in Europe and North America. Global Change Biology, 12(9), 1608-1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01213.x | Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal | Nathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat | <p>Background: Biological invasions are major anthropogenic changes associated with threats to biodiversity and health. What determines the successful establishment of introduced populations still remains unsolved. Here we explore the appealing as... |  | Biological invasions, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Population ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2018-10-14 12:21:52 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheriesEric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905“Hidden” natural selection and the evolution of body size in harvested stocksRecommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are exploiting biological resources since thousands of years. Exploitation of biological resources has become particularly intense since the beginning of the 20th century and the steep increase in the worldwide human population size. Marine and freshwater fishes are not exception to that rule, and they have been (and continue to be) strongly harvested as a source of proteins for humans. For some species, fishery has been so intense that natural stocks have virtually collapsed in only a few decades. The worst example begin that of the Northwest Atlantic cod that has declined by more than 95% of its historical biomasses in only 20-30 years of intensive exploitation (Frank et al. 2005). These rapid and steep changes in biomasses have huge impacts on the entire ecosystems since species targeted by fisheries are often at the top of trophic chains (Frank et al. 2005). Beyond demographic impacts, fisheries also have evolutionary impacts on populations, which can also indirectly alter ecosystems (Uusi-Heikkilä et al. 2015; Palkovacs et al. 2018). Fishermen generally focus on the largest specimens, and hence exert a strong selective pressure against these largest fish (which is called “harvest selection”). There is now ample evidence that harvest selection can lead to rapid evolutionary changes in natural populations toward small individuals (Kuparinen & Festa-Bianchet 2017). These evolutionary changes are of course undesirable from a human perspective, and have attracted many scientific questions. Nonetheless, the consequence of harvest selection is not always observable in natural populations, and there are cases in which no phenotypic change (or on the contrary an increase in mean body size) has been observed after intense harvest pressures. In a conceptual Essay, Edeline and Loeuille (Edeline & Loeuille 2020) propose novel ideas to explain why the evolutionary consequences of harvest selection can be so diverse, and how a cross talk between ecological and evolutionary dynamics can explain patterns observed in natural stocks. The general and novel concept proposed by Edeline and Loeuille is actually as old as Darwin’s book; The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It is based on the simple idea that natural selection acting on harvested populations can actually be strong, and counter-balance (or on the contrary reinforce) the evolutionary consequence of harvest selection. Although simple, the idea that natural and harvest selection are jointly shaping contemporary evolution of exploited populations lead to various and sometimes complex scenarios that can (i) explain unresolved empirical patterns and (ii) refine predictions regarding the long-term viability of exploited populations. The Edeline and Loeuille’s crafty inspiration is that natural selection acting on exploited populations is itself an indirect consequence of harvest (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). They suggest that, by modifying the size structure of populations (a key parameter for ecological interactions), harvest indirectly alters interactions between populations and their biotic environment through competition and predation, which changes the ecological theatre and hence the selective pressures acting back to populations. They named this process “size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedback loops” and develop several scenarios in which these feedback loops ultimately deviate the evolutionary outcome of harvest selection from expectation. The scenarios they explore are based on strong theoretical knowledge, and range from simple ones in which a single species (the harvest species) is evolving to more complex (and realistic) ones in which multiple (e.g. the harvest species and its prey) species are co-evolving. I will not come into the details of each scenario here, and I will let the readers (re-)discovering the complex beauty of biological life and natural selection. Nonetheless, I will emphasize the importance of considering these eco-evolutionary processes altogether to fully grasp the response of exploited populations. Edeline and Loeuille convincingly demonstrate that reduced body size due to harvest selection is obviously not the only response of exploited fish populations when natural selection is jointly considered (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). On the contrary, they show that –under some realistic ecological circumstances relaxing exploitative competition due to reduced population densities- natural selection can act antagonistically, and hence favour stable body size in exploited populations. Although this seems further desirable from a human perspective than a downsizing of exploited populations, it is actually mere window dressing as Edeline and Loeuille further showed that this response is accompanied by an erosion of the evolvability –and hence a lowest probability of long-term persistence- of these exploited populations. Humans, by exploiting biological resources, are breaking the relative equilibrium of complex entities, and the response of populations to this disturbance is itself often complex and heterogeneous. In this Essay, Edeline and Loeuille provide –under simple terms- the theoretical and conceptual bases required to improve predictions regarding the evolutionary responses of natural populations to exploitation by humans (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). An important next step will be to generate data and methods allowing confronting the empirical reality to these novel concepts (e.g. (Monk et al. 2021), so as to identify the most likely evolutionary scenarios sustaining biological responses of exploited populations, and hence to set the best management plans for the long-term sustainability of these populations. References Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. John Murray, London. Edeline, E. & Loeuille, N. (2021) Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries. bioRxiv, 2020.04.03.022905, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905 Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J. S. & Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem. Science, 308, 1621–1623. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113075 Kuparinen, A. & Festa-Bianchet, M. (2017). Harvest-induced evolution: insights from aquatic and terrestrial systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 372, 20160036. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0036 Monk, C.T., Bekkevold, D., Klefoth, T., Pagel, T., Palmer, M. & Arlinghaus, R. (2021). The battle between harvest and natural selection creates small and shy fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2009451118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009451118 Palkovacs, E.P., Moritsch, M.M., Contolini, G.M. & Pelletier, F. (2018). Ecology of harvest-driven trait changes and implications for ecosystem management. Front. Ecol. Environ., 16, 20–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1743 Uusi-Heikkilä, S., Whiteley, A.R., Kuparinen, A., Matsumura, S., Venturelli, P.A., Wolter, C., et al. (2015). The evolutionary legacy of size-selective harvesting extends from genes to populations. Evol. Appl., 8, 597–620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12268 | Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries | Eric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Harvesting may drive body downsizing along with population declines and decreased harvesting yields. These changes are commonly construed as direct consequences of harvest selection, where small-bodied, early-reproducing individuals are immedia... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Competition, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Food webs, Interaction networks, Life history, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2020-04-03 16:14:05 | View | |

06 Mar 2020

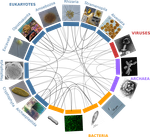

A community perspective on the concept of marine holobionts: current status, challenges, and future directionsSimon M. Dittami, Enrique Arboleda, Jean-Christophe Auguet, Arite Bigalke, Enora Briand, Paco Cárdenas, Ulisse Cardini, Johan Decelle, Aschwin Engelen, Damien Eveillard, Claire M.M. Gachon, Sarah Griffiths, Tilmann Harder, Ehsan Kayal, Elena Kazamia, Francois H. Lallier, Mónica Medina, Ezequiel M. Marzinelli, Teresa Morganti, Laura Núñez Pons, Soizic Pardo, José Pintado Valverde, Mahasweta Saha, Marc-André Selosse, Derek Skillings, Willem Stock, Shinichi Sunagawa, Eve Toulza, Alexey Vorobev, Cat... 10.5281/zenodo.3696771Marine holobiont in the high throughput sequencing eraRecommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond and Corinne Vacher based on reviews by Sophie Arnaud-Haond and Aurélie TasiemskiThe concept of holobiont dates back to more than thirty years, it was primarily coined to hypothesize the importance of symbiotic associations to generate significant evolutionary novelties. Quickly adopted to describe the now well-studied system formed by zooxanthella associated corals, this concept expanded much further after the emergence of High-Throughput Sequencing and associated progresses in metabarcoding and metagenomics. References | A community perspective on the concept of marine holobionts: current status, challenges, and future directions | Simon M. Dittami, Enrique Arboleda, Jean-Christophe Auguet, Arite Bigalke, Enora Briand, Paco Cárdenas, Ulisse Cardini, Johan Decelle, Aschwin Engelen, Damien Eveillard, Claire M.M. Gachon, Sarah Griffiths, Tilmann Harder, Ehsan Kayal, Elena Kazam... | Host-microbe interactions play crucial roles in marine ecosystems. However, we still have very little understanding of the mechanisms that govern these relationships, the evolutionary processes that shape them, and their ecological consequences. T... |  | Marine ecology, Microbial ecology & microbiology, Symbiosis | Sophie Arnaud-Haond | 2019-02-05 17:57:11 | View | |

02 Dec 2021

Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289The promise and limits of DNA based approach to infer diet flexibility in endangered top predatorsRecommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond based on reviews by Francis John Burdon and Babett GüntherThere is growing evidence of worldwide decline of populations of top predators, including marine ones (Heithaus et al, 2008, Mc Cauley et al., 2015), with cascading effects expected at the ecosystem level, due to global change and human activities, including habitat loss or fragmentation, the collapse or the range shifts of their preys. On a global scale, seabirds are among the most threatened group of birds, about one-third of them being considered as threatened or endangered (Votier& Sherley, 2017). The large consequences of the decrease of the populations of preys they feed on (Cury et al, 2011) points diet flexibility as one important element to understand for effective management (McInnes et al, 2017). Nevertheless, morphological inventory of preys requires intrusive protocols, and the differential digestion rate of distinct taxa may lead to a large bias in morphological-based diet assessments. The use of DNA metabarcoding on feces (or diet DNA, dDNA) now allows non-invasive approaches facilitating the recollection of samples and the detection of multiple preys independently of their digestion rates (Deagle et al., 2019). Although no gold standard exists yet to avoid bias associated with metabarcoding (primer bias, gaps in reference databases, inability to differentiate primary from secondary predation…), the use of these recent techniques has already improved the knowledge of the foraging behaviour and diet of many animals (Ando et al., 2020). Both promise and shortcomings of this approach are illustrated in the article “Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)” by Quereteja et al. (2021). In this work, the authors assessed the nature and spatio-temporal flexibility of the foraging behaviour and consequent diet of the endangered petrel Procellaria westlandica from New-Zealand through metabarcoding of faeces samples. The results of this dDNA, non-invasive approach, identify some expected and also unexpected prey items, some of which require further investigation likely due to large gaps in the reference databases. They also reveal the temporal (before and after hatching) and spatial (across colonies only 1.5km apart) flexibility of the foraging behaviour, additionally suggesting a possible influence of fisheries activities in the surroundings of the colonies. This study thus both underlines the power of the non-invasive metabarcoding approach on faeces, and the important results such analysis can deliver for conservation, pointing a potential for diet flexibility that may be essential for the resilience of this iconic yet endangered species. References Ando H, Mukai H, Komura T, Dewi T, Ando M, Isagi Y (2020) Methodological trends and perspectives of animal dietary studies by noninvasive fecal DNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 2, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.117 Cury PM, Boyd IL, Bonhommeau S, Anker-Nilssen T, Crawford RJM, Furness RW, Mills JA, Murphy EJ, Österblom H, Paleczny M, Piatt JF, Roux J-P, Shannon L, Sydeman WJ (2011) Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion—One-Third for the Birds. Science, 334, 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212928 Deagle BE, Thomas AC, McInnes JC, Clarke LJ, Vesterinen EJ, Clare EL, Kartzinel TR, Eveson JP (2019) Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 28, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14734 Heithaus MR, Frid A, Wirsing AJ, Worm B (2008) Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.003 McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347, 1255641. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641 McInnes JC, Jarman SN, Lea M-A, Raymond B, Deagle BE, Phillips RA, Catry P, Stanworth A, Weimerskirch H, Kusch A, Gras M, Cherel Y, Maschette D, Alderman R (2017) DNA Metabarcoding as a Marine Conservation and Management Tool: A Circumpolar Examination of Fishery Discards in the Diet of Threatened Albatrosses. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00277 Querejeta M, Lefort M-C, Bretagnolle V, Boyer S (2021) Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). bioRxiv, 2020.10.30.360289, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289 Votier SC, Sherley RB (2017) Seabirds. Current Biology, 27, R448–R450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.042 | Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica) | Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer | <p style="text-align: justify;">As top predators, seabirds can be indirectly impacted by climate variability and commercial fishing activities through changes in marine communities. However, high mobility and foraging behaviour enables seabirds to... |  | Conservation biology, Food webs, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Sophie Arnaud-Haond | 2020-10-30 20:14:50 | View | |

29 Nov 2019

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalAugust Sevchik, Corina Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Aaron Blackwell, Carolyn Rowney, Dieter Lukas http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gdispersal.htmlInvestigate fine scale sex dispersal with spatial and genetic analysesRecommended by Sophie Beltran-Bech based on reviews by Sylvine Durand and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Sylvine Durand and 1 anonymous reviewer

The preregistration "Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal" [1] presents the analysis plan that will be used to genetically and spatially investigate sex-biased dispersal in great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). References [1] Sevchik A., Logan C. J., Folsom M., Bergeron L., Blackwell A., Rowney C., and Lukas D. (2019). Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gdispersal.html | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | August Sevchik, Corina Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Aaron Blackwell, Carolyn Rowney, Dieter Lukas | In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain close to the place they were hatched for their entire lives (Greenwood and Harvey (1982)). Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have f... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Life history, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Sophie Beltran-Bech | 2019-07-24 12:47:07 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora coralsK. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza https://doi.org/10.1101/398602Transcriptomics of thermal stress response in coralsRecommended by Staffan Jacob based on reviews by Mar SobralClimate change presents a challenge to many life forms and the resulting loss of biodiversity will critically depend on the ability of organisms to timely respond to a changing environment. Shifts in ecological parameters have repeatedly been attributed to global warming, with the effectiveness of these responses varying among species [1, 2]. Organisms do not only have to face a global increase in mean temperatures, but a complex interplay with another crucial but largely understudied aspect of climate change: thermal fluctuations. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adaptation to thermal fluctuations is thus a timely and critical challenge. References [1] Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286 | Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora corals | K. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza | <p>Ecosystems worldwide are suffering from climate change. Coral reef ecosystems are globally threatened by increasing sea surface temperatures. However, gene expression plasticity provides the potential for organisms to respond rapidly and effect... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Symbiosis | Staffan Jacob | 2018-08-29 10:46:55 | View | |

05 Feb 2020

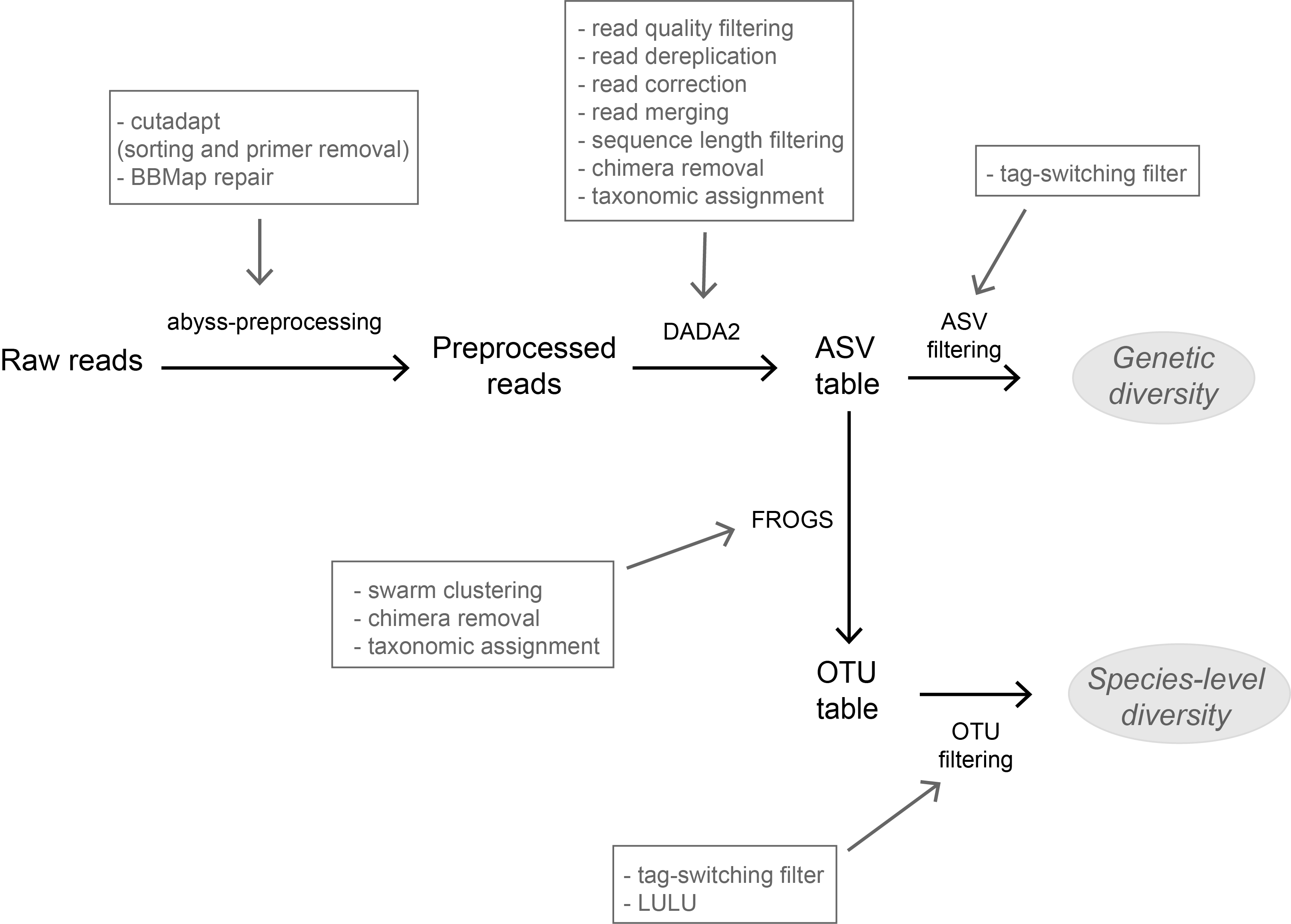

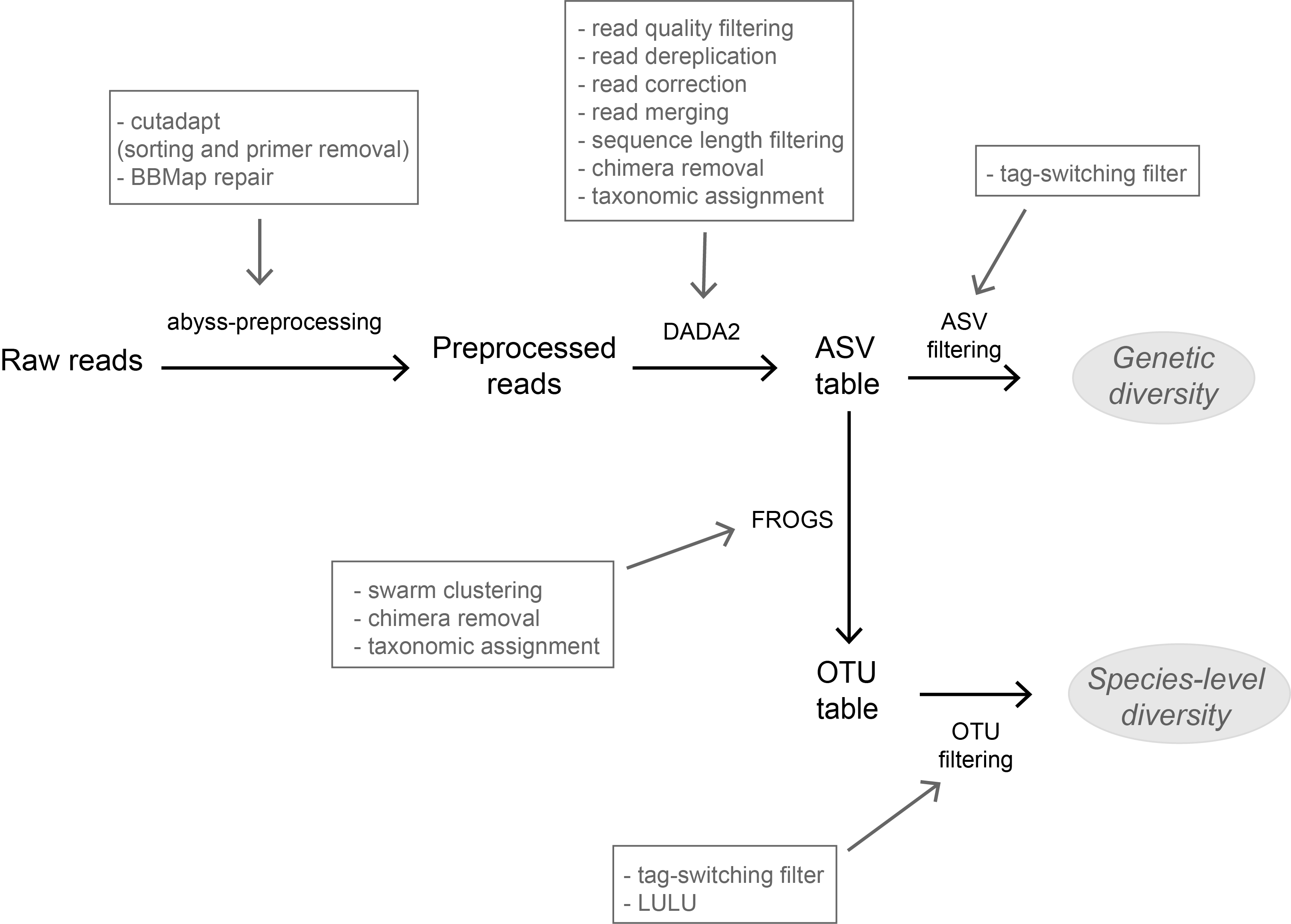

A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingMiriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://doi.org/10.1101/717355A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer

High-throughput sequencing-based techniques such as DNA metabarcoding are increasingly advocated as providing numerous benefits over morphology‐based identifications for biodiversity inventories and ecosystem biomonitoring [1]. These benefits are particularly apparent for highly-diversified and/or hardly accessible aquatic and marine environments, where simple water or sediment samples could already produce acceptably accurate biodiversity estimates based on the environmental DNA present in the samples [2,3]. However, sequence-based characterization of biodiversity comes with its own challenges. A major one resides in the capacity to disentangle true biological diversity (be it taxonomic or genetic) from artefactual diversity generated by sequence-errors accumulation during PCR and sequencing processes, or from the amplification of non-target genes (i.e. pseudo-genes). On one hand, the stringent elimination of sequence variants might lead to biodiversity underestimation through the removal of true species, or the clustering of closely-related ones. On the other hand, a more permissive sequence filtering bears the risks of biodiversity inflation. Recent studies have outlined an excellent methodological framework for addressing this issue by proposing bioinformatic tools that allow the amplicon-specific error-correction as alternative or as complement to the more arbitrary approach of clustering into Molecular Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) based on sequence dissimilarity [4,5]. But to date, the relevance of amplicon-specific error-correction tools has been demonstrated only for a limited set of taxonomic groups and gene markers. References [1] Porter, T. M., and Hajibabaei, M. (2018). Scaling up: A guide to high-throughput genomic approaches for biodiversity analysis. Molecular Ecology, 27(2), 313–338. doi: 10.1111/mec.14478 | A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcoding | Miriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Environmental metabarcoding is an increasingly popular tool for studying biodiversity in marine and terrestrial biomes. With sequencing costs decreasing, multiple-marker metabarcoding, spanning several branches of the tree of life, is becoming ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-08-02 20:52:45 | View | |

20 Oct 2021

Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population declineAvril Weinbach, Nicolas Loeuille, Rudolf P. Rohr https://doi.org/10.1101/570580Doomed by your partner: when mutualistic interactions are like an evolutionary millstone around a species’ neckRecommended by Sylvain Billiard based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Mutualistic interactions are the weird uncles of population and community ecology. They are everywhere, from the microbes aiding digestion in animals’ guts to animal-pollination services in ecosystems; They increase productivity through facilitation; They fascinate us when small birds pick the teeth of a big-mouthed crocodile. Yet, mutualistic interactions are far less studied and understood than competition or predation. Possibly because we are naively convinced that there is no mystery here: isn’t it obvious that mutualistic interactions necessarily facilitate species coexistence? Since mutualistic species benefit from one another, if one species evolves, the other should just follow, isn’t that so? It is not as simple as that, for several reasons. First, because simple mutualistic Lotka-Volterra models showed that most of the time mutualistic systems should drift to infinity and be unstable (e.g. Goh 1979). This is not what happens in natural populations, so something is missing in simple models. At a larger scale, that of communities, this is even worse, since we are still far from understanding the link between the topology of mutualistic networks and the stability of a community. Second, interactions are context-dependent: mutualistic species exchange resources, and thus from the point of view of one species the interaction is either beneficial or not, depending on the net gain of energy (e.g. Holland and DeAngelis 2010). In other words, considering interactions as mutualistic per se is too caricatural. Third, since evolution is blind, the evolutionary response of a species to an environmental change can have any effect on its mutualistic partner, and not necessarily a neutral or positive effect. This latter reason is particularly highlighted by the paper by A. Weinbach et al. (2021). Weinbach et al. considered a simple two-species mutualistic Lotka-Volterra model and analyzed the evolutionary dynamics of a trait controlling for the rate of interaction between the two species by using the classical Adaptive Dynamics framework. They showed that, depending on the form of the trade-off between this interaction trait and its effect on the intrinsic growth rate, several situations can occur at evolutionary equilibrium: species can stably coexist and maintain their interaction, or the interaction traits can evolve to zero where species can coexist without any interactions. Weinbach et al. then investigated the fate of the two-species system if a partner species is strongly affected by environmental change, for instance, a large decrease of its growth rate. Because of the supposed trade-off between the interaction trait and the growth rate, the interaction trait in the focal species tends to decrease as an evolutionary response to the decline of the partner species. If environmental change is too large, the interaction trait can evolve to zero and can lead the partner species to extinction. An “evolutionary murder”. Even though Weinbach et al. interpreted the results of their model through the lens of plant-pollinators systems, their model is not specific to this case. On the contrary, it is very general, which has advantages and caveats. By its generality, the model is informative because it is a proof of concept that the evolution of mutualistic interactions can have unexpected effects on any category of mutualistic systems. Yet, since the model lacks many specificities of plant-pollinator interactions, it is hard to evaluate how their result would apply to plant-pollinators communities. I wanted to recommend this paper as a reminder that it is certainly worth studying the evolution of mutualistic interactions, because i) some unexpected phenomenons can occur, ii) we are certainly too naive about the evolution and ecology of mutualistic interactions, and iii) one can wonder to what extent we will be able to explain the stability of mutualistic communities without accounting for the co-evolutionary dynamics of mutualistic species. References Goh BS (1979) Stability in Models of Mutualism. The American Naturalist, 113, 261–275. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2460204. Holland JN, DeAngelis DL (2010) A consumer–resource approach to the density-dependent population dynamics of mutualism. Ecology, 91, 1286–1295. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1163.1 Weinbach A, Loeuille N, Rohr RP (2021) Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population decline. bioRxiv, 570580, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/570580 | Eco-evolutionary dynamics further weakens mutualistic interaction and coexistence under population decline | Avril Weinbach, Nicolas Loeuille, Rudolf P. Rohr | <p style="text-align: justify;">With current environmental changes, evolution can rescue declining populations, but what happens to their interacting species? Mutualistic interactions can help species sustain each other when their environment wors... |  | Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Interaction networks, Pollination, Theoretical ecology | Sylvain Billiard | 2019-09-05 11:29:45 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle