Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 May 2021

Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at behavioral inhibition?Logan CJ, McCune KB, MacPherson M, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Rowney C, Seitz B, Blaisdell AP, Deffner D, Wascher CAF https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vpc39Great-tailed grackle research reveals need for researchers to consider their own flexibility and test limitations in cognitive test batteries.Recommended by Aliza le Roux based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Alex DeCasianIn the article, "Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at behavioral inhibition?", Logan and colleagues (2021) are setting an excellent standard for cognitive research on wild-caught animals. Using a decent sample (N=18) of wild-caught birds, they set out to test the ambiguous link between behavioral flexibility and behavioral inhibition, which is supported by some studies but rejected by others. Where this study is more thorough and therefore also more revealing than most extant research, the authors ran a battery of tests, examining both flexibility (reversal learning and solution switching) and inhibition (go/no go task; detour task; delay of gratification) through multiple different test series. They also -- somewhat accidentally -- performed their experiments and analyses with and without different criteria for correctness (85%, 100%). Their mistakes, assumptions and amendments of plans made during preregistration are clearly stated and this demonstrates the thought-process of the researchers very clearly. Logan et al. (2021) show that inhibition in great-tailed grackles is a multi-faceted construct, and demonstrate that the traditional go/no go task likely tests a very different aspect of inhibition than the detour task, which was never linked to any of their flexibility measures. Their comprehensive Bayesian analyses held up the results of some of the frequentist statistics, indicating a consistent relationship between flexibility and inhibition, with more flexible individuals also showing better inhibition (in the go/no go task). This same model, combined with inconsistencies in the GLM analyses (depending on the inclusion or exclusion of an outlier), led them to recommend caution in the creation of arbitrary thresholds for "success" in any cognitive tasks. Their accidental longer-term data collection also hinted at patterns of behaviour that shorter-term data collection did not. Of course, researchers have to decide on success criteria in order to conduct experiments, but in the same way that frequentist statistics are acknowledged to have flaws, the setting of success criteria must be acknowledged as inherently arbitrary. Where possible, researchers could reveal novel, biologically salient patterns by continuing beyond the point where a convenient success criterion has been reached. This research also underscores that tests may not be examining the features we expected them to measure, and are highly sensitive to biological and ecological variation between species as well as individual variation within populations. To me, this study is an excellent argument for pre-registration of research (registered as Logan et al. 2019 and accepted by Vogel 2019), as the authors did not end up cherry-picking only those results or methods that worked. The fact that some of the tests did not "work", but was still examined, added much value to the study. The current paper is a bit densely written because of the comprehensiveness of the research. Some editorial polishing would likely make for more elegant writing. However, the arguments are clear, the results novel, and the questions thoroughly examined. The results are important not only for cognitive research on birds, but are potentially valuable to any cognitive scientist. I recommend this article as excellent food for thought. References Logan CJ, McCune K, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell AP, Wascher CAF. (2019) Are the more flexible individuals also better at inhibition? http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_inhibition.html In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version on 6 Mar 2019 Logan CJ, McCune KB, MacPherson M, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Rowney C, Seitz B, Blaisdell AP, Deffner D, Wascher CAF (2021) Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at behavioral inhibition? PsyArXiv, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vpc39 Vogel E (2019) Adapting to a changing environment: advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility. Peer Community in Ecology, 100016. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100016 | Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at behavioral inhibition? | Logan CJ, McCune KB, MacPherson M, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Rowney C, Seitz B, Blaisdell AP, Deffner D, Wascher CAF | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility (hereafter, flexibility) should theoretically be positively related to behavioral inhibition (hereafter, inhibition) because one should need to inhibit a previously learned behavior to change ... | Preregistrations | Aliza le Roux | 2020-12-04 13:57:07 | View | ||

13 Jul 2023

Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predatorsLoïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552Indirect effects of parasitism include increased profitability of prey to optimal foragersRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Thierry DE MEEUS and Eglantine Mathieu-BégnéEven though all living organisms are, at the same time, involved in host-parasite interactions and embedded in complex food webs, the indirect effects of parasitism are only beginning to be unveiled. Prosnier et al. investigated the direct and indirect effects of parasitism making use of a very interesting biological system comprising the freshwater zooplankton Daphnia magna and its highly specific parasite, the iridovirus DIV-1 (Daphnia-iridescent virus 1). Daphnia are typically semitransparent, but once infected develop a white phenotype with a characteristic iridescent shine due to the enlargement of white fat cells. In a combination of infection trials and comparison of white and non-white phenotypes collected in natural ponds, the authors demonstrated increased mortality and reduced lifetime fitness in infected Daphnia. Furthermore, white phenotypes had lower mobility, increased reflectance, larger body sizes and higher protein content than non-white phenotypes. As a consequence, total energy content was effectively doubled in white Daphnia when compared to non-white broodless Daphnia. Next the authors conducted foraging trials with Daphnia predators Notonecta (the backswimmer) and Phoxinus (the European minnow). Focusing on Notonecta, unchanged search time and increased handling time were more than compensated by the increased energy content of white Daphnia. White Daphnia were 24% more profitable and consistently preferred by Notonecta, as the optimal foraging theory would predict. The authors argue that menu decisions of optimal foragers in the field might be different, however, as the prevalence – and therefore availability - of white phenotypes in natural populations is very low. The study therefore contributes to our understanding of the trophic context of parasitism. One shortcoming of the study is that the authors rely exclusively on phenotypic signs for determining infection. On their side, DIV-1 is currently known to be highly specific to Daphnia, their study site is well within DIV-1 distributional range, and the symptoms of infection are very conspicuous. Furthermore, the infection trial – in which non-white Daphnia were exposed to white Daphnia homogenates - effectively caused several lethal and sublethal effects associated with DIV-1 infection, including iridescence. However, the infection trial also demonstrated that part of the exposed individuals developed intermediate traits while still keeping the non-white, non-iridescent phenotype. Thus, there may be more subtleties to the association of DIV-1 infection of Daphnia with ecological and evolutionary consequences, such as costs to resistance or covert infection, that the authors acknowledge, and that would be benefitted by coupling experimental and observational studies with the determination of actual infection and viral loads. References Prosnier L., N. Loeuille, F.D. Hulot, D. Renault, C. Piscart, B. Bicocchi, M, Deparis, M. Lam, & V. Médoc. (2023). Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552 | Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators | Loïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc | <p>Parasites are omnipresent, and their eco-evolutionary significance has aroused much interest from scientists. Parasites may affect their hosts in many ways by altering host density, vulnerability to predation, and energy content, thus modifying... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Epidemiology, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Life history, Parasitology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2022-05-20 10:15:41 | View | |

24 May 2023

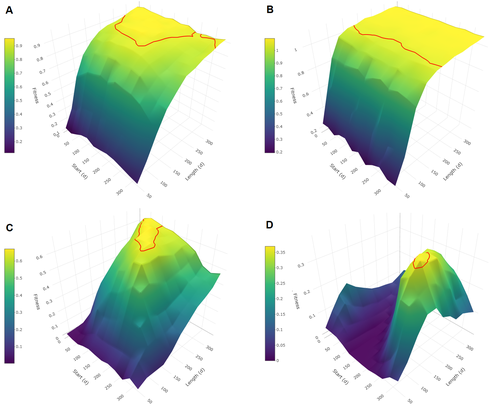

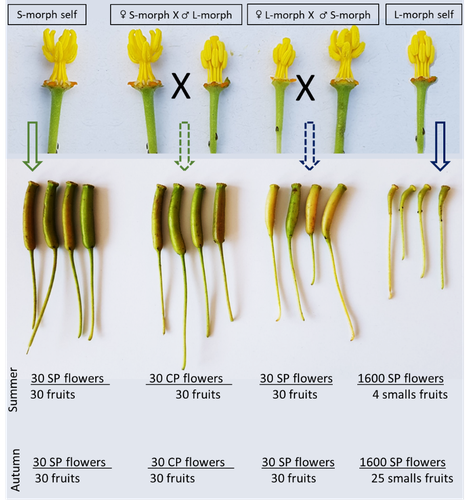

Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approachLugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761When does seasonal reproduction evolve?Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer

Have you ever wondered why some species breed seasonally while others do not? You might think it is all down to lattitude and the harshness of winters but it turns out it is quite a bit more complicated than that. A consequence of this is that climate change may result in the evolution of the degree of seasonal reproduction, with some species perhaps becoming less seasonal and others more so even in the same habitat. Burtschell et al. (2023) investigated how various factors influence seasonal breeding by building an individual-based model of a baboon population from which they calculated the degree of seasonality for the fittest reproductive strategy. They then altered key aspects of their model to examine how these changes impacted the degree of seasonality in the reproductive strategy. What they found is fascinating. The degree of seasonality in reproductive strategy is expected to increase with increased seasonality in the environment, decreased food availability, increased energy expenditure, and how predictable resource availability is. Interestingly, neither female cycle length nor extrinsic infant mortality influenced the degree of seasonality in reproduction. What this means in reality for seasonal species is more challenging to understand. Some environments appear to be becoming more seasonal yet less predictable, and some species appear to be altering their daily energy budgets in response to changing climate in quite complex ways. As with pretty much everything in biology, Burtschell et al.'s work reveals much nuance and complexity, and that predicting how species might alter their reproductive timing is fraught with challenges. The paper is very well written. With a simpler model it may have proven possible to achieve analytical solutions, but this is a very minor gripe. The reviewers were positive about the paper, and I have little doubt it will be well-cited. REFERENCES Burtschell L, Dezeure J, Huchard E, Godelle B (2023) Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, 2022.08.22.504761, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761 | Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach | Lugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle | <p style="text-align: justify;">Reproductive seasonality is a major adaptation to seasonal cycles and varies substantially among organisms. This variation, which was long thought to reflect a simple latitudinal gradient, remains poorly understood ... |  | Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Theoretical ecology | Tim Coulson | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-23 21:37:28 | View |

05 Apr 2022

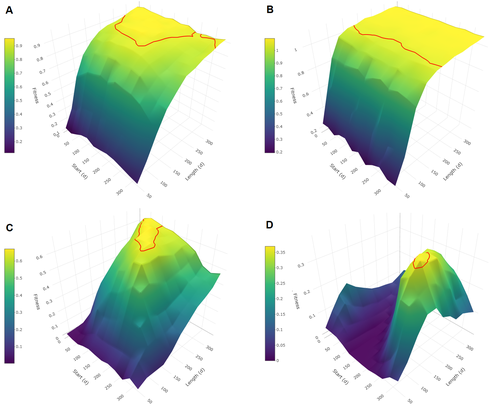

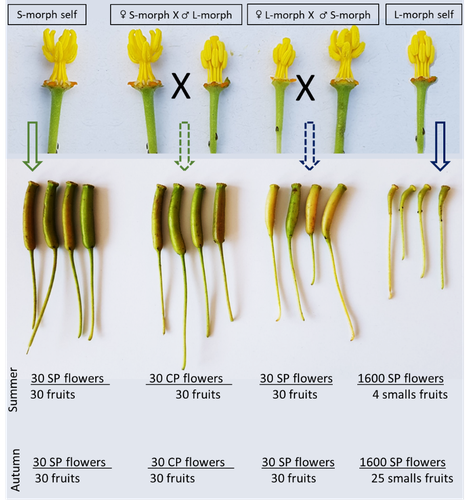

Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetalaLuis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457Water primerose (Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala) auto- and allogamy: an ecological perspectiveRecommended by Antoine Vernay based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer

Invasive plant species are widely studied by the ecologist community, especially in wetlands. Indeed, alien plants are considered one of the major threats to wetland biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019). Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G.L.Nesom & Kartesz, 2000 (Lgh) is one of them and has received particular attention for a long time (Hieda et al., 2020; Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiebaut, 2013). The ecology of this invasive species and its effect on its biotic and abiotic environment has been studied in previous works. Different processes were demonstrated to explain their invasibility such as allelopathic interference (Dandelot et al., 2008), resource competition (Gérard et al., 2014), and high phenotypic plasticity (Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiébaut, 2013), to cite a few of them. However, although vegetative reproduction is a well-known invasive process for alien plants like Lgh (Glover et al., 2015), the sexual reproduction of this species is still unclear and may help to understand the Lgh population dynamics. Portillo Lemus et al. (2021) showed that two floral morphs of Lgh co-exist in natura, involving self-compatibility for short-styled phenotype and self-incompatibility for long-styled phenotype processes. This new article (Portillo Lemus et al., 2022) goes further and details the underlying mechanisms of the sexual reproduction of the two floral morphs. Complementing their previous study, the authors have described a late self-incompatible process associated with the long-styled morph, which authorized a small proportion of autogamy. Although this represents a small fraction of the L-morph reproduction, it may have a considerable impact on the L-morph population dynamics. Indeed, authors report that “floral morphs are mostly found in allopatric monomorphic populations (i.e., exclusively S-morph or exclusively L-morph populations)” with a large proportion of L-morph populations compared to S-morph populations in the field. It may seem counterintuitive as L-morph mainly relies on cross-fecundation. Results show that L-morph autogamy mainly occurs in the fall, late in the reproduction season. Therefore, the reproduction may be ensured if no exogenous pollen reaches the stigma of L-morph individuals. It partly explains the large proportion of L-morph populations in the field. Beyond the description of late-acting self-incompatibility, which makes the Onagraceae a third family of Myrtales with this reproductive adaptation, the study raises several ecological questions linked to the results presented in the article. First, it seems that even if autogamy is possible, Lgh would favour allogamy, even in S-morph, through the faster development of pollen tubes from other individuals. This may confer an adaptative and evolutive advantage for the Lgh, increasing its invasive potential. The article shows this faster pollen tube development in S-morph but does not test the evolutive consequences. It is an interesting perspective for future research. It would also be interesting to describe cellular processes which recognize and then influence the speed of the pollen tube. Second, the importance of sexual reproduction vs vegetative reproduction would also provide information on the benefits of sexual dimorphism within populations. For instance, how fruit production increases the dispersal potential of Lgh would help to understand Lgh population dynamics and to propose adapted management practices (Delbart et al., 2013; Meisler, 2009). To conclude, the study proposes a morphological, reproductive and physiological description of the Lgh sexual reproduction process. However, underlying ecological questions are well included in the article and the ecophysiological results enlighten some questions about the role of sexual reproduction in the invasiveness of Lgh. I advise the reader to pay attention to the reviewers’ comments; the debates were very constructive and, thanks to the great collaboration with the authorship, lead to an interesting paper about Lgh reproduction and with promising perspectives in ecology and invasion ecology. References Dandelot S, Robles C, Pech N, Cazaubon A, Verlaque R (2008) Allelopathic potential of two invasive alien Ludwigia spp. Aquatic Botany, 88, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.004 Delbart E, Mahy G, Monty A (2013) Efficacité des méthodes de lutte contre le développement de cinq espèces de plantes invasives amphibies : Crassula helmsii, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Ludwigia grandiflora, Ludwigia peploides et Myriophyllum aquaticum (synthèse bibliographique). BASE, 17, 87–102. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=9586 Gérard J, Brion N, Triest L (2014) Effect of water column phosphorus reduction on competitive outcome and traits of Ludwigia grandiflora and L. peploides, invasive species in Europe. Aquatic Invasions, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.04 Glover R, Drenovsky RE, Futrell CJ, Grewell BJ (2015) Clonal integration in Ludwigia hexapetala under different light regimes. Aquatic Botany, 122, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.01.004 Hieda S, Kaneko Y, Nakagawa M, Noma N (2020) Ludwigia grandiflora (Michx.) Greuter & Burdet subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G. L. Nesom & Kartesz, an Invasive Aquatic Plant in Lake Biwa, the Largest Lake in Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica, 71, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.201911 Meisler J (2009) Controlling Ludwigia hexaplata in Northern California. Wetland Science and Practice, 26, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1672/055.026.0404 Portillo Lemus LO, Harang M, Bozec M, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2022) Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heteromorphic invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala. bioRxiv, 2021.07.15.452457, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457 Portillo Lemus LO, Bozec M, Harang M, Coudreuse J, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2021) Self-incompatibility limits sexual reproduction rather than environmental conditions in an invasive water primrose. Plant-Environment Interactions, 2, 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10042 Reid AJ, Carlson AK, Creed IF, Eliason EJ, Gell PA, Johnson PTJ, Kidd KA, MacCormack TJ, Olden JD, Ormerod SJ, Smol JP, Taylor WW, Tockner K, Vermaire JC, Dudgeon D, Cooke SJ (2019) Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews, 94, 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12480 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G (2013) A success story: water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 23, 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiébaut G (2013) Seasonal plasticity of Ludwigia grandiflora under light and water depth gradients: An outdoor mesocosm experiment. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 208, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.004 | Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala | Luis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding system influences local population genetic structure, effective size, offspring fitness and functional variation. Determining the respective importance of self- and cross-fertilization in hermaphroditic flo... |  | Biological invasions, Botany, Freshwater ecology, Pollination | Antoine Vernay | 2021-07-16 09:53:50 | View | |

15 Feb 2024

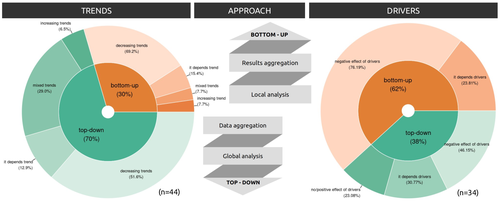

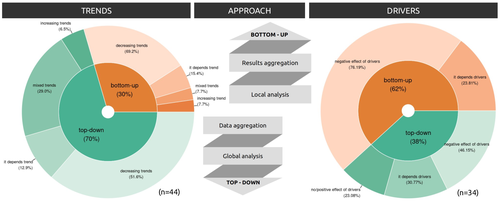

Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trendsMaelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3HUnraveling the Complexity of Global Biodiversity Dynamics: Insights and ImperativesRecommended by Paulo Borges based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer

Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across terrestrial and marine ecosystems, driven by various processes that degrade habitats and threaten species with extinction. Despite the urgency of this issue, empirical studies present a mixed picture, with some indicating declining trends while others show more complex patterns. In a recent effort to better understand global biodiversity dynamics, Boennec et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive literature review examining temporal trends in biodiversity. Their analysis reveals that reviews and meta-analyses, coupled with the use of global indicators, tend to report declining trends more frequently. Additionally, the study underscores a critical gap in research: the scarcity of investigations into the combined impact of multiple pressures on biodiversity at a global scale. This lack of understanding complicates efforts to identify the root causes of biodiversity changes and develop effective conservation strategies. This study serves as a crucial reminder of the pressing need for long-term biodiversity monitoring and large-scale conservation studies. By filling these gaps in knowledge, researchers can provide policymakers and conservation practitioners with the insights necessary to mitigate biodiversity loss and safeguard ecosystems for future generations. References Boennec, M., Dakos, V. & Devictor, V. (2023). Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trend. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3H

| Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trends | Maelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor | <p>Populations and ecological communities are changing worldwide, and empirical studies exhibit a mixture of either declining or mixed trends. Confusion in global biodiversity trends thus remains while assessing such changes is of major social, po... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Meta-analyses | Paulo Borges | 2023-09-20 11:10:25 | View | |

14 Jul 2023

Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlandsMallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780Searching for conservation opportunities at the marginsRecommended by Ana S. L. Rodrigues based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D Concepción

In a progressively human-dominated planet (Venter et al., 2016), the fate of many species will depend on the extent to which they can persist in anthropogenic landscapes. In Western Europe, where only small areas of primary habitat remain (e.g. Sabatini et al., 2018), semi-natural areas are crucial habitats to many native species, yet they are threatened by the expansion of human activities, including agricultural expansion and intensification (Rigal et al., 2023). A new study by Mallet and colleagues (Mallet et al., 2023) investigates the extent to which bird species in the Camargue region are able to use the margins of agricultural fields as substitutes for their preferred semi-natural habitats. Located in the delta of the Rhône River in Southern France, the Camargue is internationally recognized for its biodiversity value, classified as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO and as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention (IUCN & UN-WCMC, 2023). Mallet and colleagues tested three specific hypotheses: that grass strips (grassy field boundaries, including grassy tracks or dirt roads used for moving agricultural machinery) can function as substitute habitats for grassland species; that reed strips along drainage ditches (common in the rice paddy landscapes of the Camargue) can function as substitute habitats to wetland species; and that hedgerows can function as substitute habitats to species that favour woodland edges. They did so by measuring how the local abundances of 14 bird species (nine typical of forest edges, 3 of grasslands, and two of reedbeds) respond to increasing coverage of either the three types of field margins or of the three types of semi-natural habitat. This is an elegant study design, yet – as is often the case with real field data – results are not as simple as expected. Indeed, for most species (11 out of 14) local abundances did not increase significantly with the area of their supposed primary habitat, undermining the assumption that they are strongly associated with (or dependent on) those habitats. Among the three species that did respond positively to the area of their primary habitat, one (a forest edge species) responded positively but not significantly to the area of field margins (hedgerows), providing weak evidence to the habitat compensation hypothesis. For the other two (grassland and a wetland species), abundance responded even more strongly to the area of field margins (grass and reed strips, respectively) than to the primary habitat, suggesting that the field margins are not so much a substitute but valuable habitats in their own right. It would have been good conservation news if field margins were found to be suitable habitat substitutes to semi-natural habitats, or at least reasonable approximations, to most species. Given that these margins have functional roles in agricultural landscapes (marking boundaries, access areas, water drainage), they could constitute good win-win solutions for reconciling biodiversity conservation with agricultural production. Alas, the results are more complicated than that, with wide variation in species responses that could not have been predicted from presumed habitat affinities. These results illustrate the challenges of conservation practice in complex landscapes formed by mosaics of variable land use types. With species not necessarily falling neatly into habitat guilds, it becomes even more challenging to plan strategically how to manage landscapes to optimize their conservation. The results presented here suggest that species’ abundances may be responding to landscape variables not taken into account in the analyses, such as connectivity between habitat patches, or maybe positive and negative edge effects between land use types. That such uncertainties remain even in a well-studied region as the Camargue, and for such a well-studied taxon such as birds, only demonstrates the continued importance of rigorous field studies testing explicit hypotheses such as this one by Mallet and colleagues. References IUCN, & UN-WCMC (2023). Protected Planet. Protected Planet. https://www.protectedplanet.net/en Mallet, P., Béchet, A., Sirami, C., Mesléard, F., Blanchon, T., Calatayud, F., Dagonet, T., Gaget, E., Leray, C., & Galewski, T. (2023). Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490780, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780 Rigal, S., Dakos, V., Alonso, H., Auniņš, A., Benkő, Z., Brotons, L., Chodkiewicz, T., Chylarecki, P., de Carli, E., del Moral, J. C. et al. (2023). Farmland practices are driving bird population decline across Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120, e2216573120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216573120 Sabatini, F. M., Burrascano, S., Keeton, W. S., Levers, C., Lindner, M., Pötzschner, F., Verkerk, P. J., Bauhus, J., Buchwald, E., Chaskovsky, O., Debaive, N. et al. (2018). Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Diversity and Distributions, 24, 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12778 Venter, O., Sanderson, E. W., Magrach, A., Allan, J. R., Beher, J., Jones, K. R., Possingham, H. P., Laurance, W. F., Wood, P., Fekete, B. M., Levy, M. A., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nature Communications, 7, 12558. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12558 | Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands | Mallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding birds in agricultural landscapes have declined considerably since the 1950s and the beginning of agricultural intensification in Europe. Given the increasing pressure on agricultural land, it is necessary t... | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Landscape ecology | Ana S. L. Rodrigues | 2022-05-09 10:48:49 | View | ||

18 Dec 2020

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islandsManuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamicsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey

Polar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). References Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043 | Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands | Manuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault | <p>Aim Here, we aim to: (i) investigate the local effect of environmental and human-related factors on alien plant invasion in sub-Antarctic islands; (ii) explore the relationship between alien species features and their dependence on anthropogeni... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2020-07-21 21:13:08 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

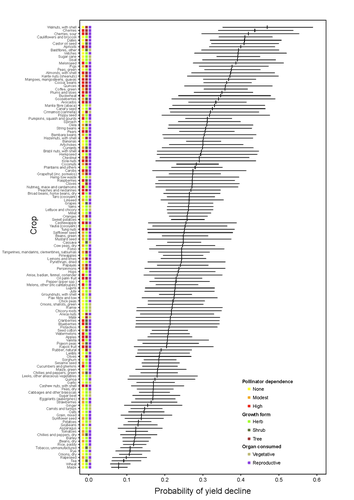

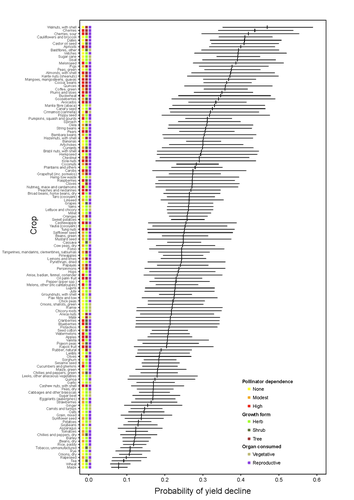

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

16 Sep 2019

Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA samplingMarie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/385120Words matter: extensive misapplication of "non-invasive" in describing DNA sampling methods, and proposed clarifying termsRecommended by Thomas Wilson Sappington based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe ability to successfully sequence trace quantities of environmental DNA (eDNA) has provided unprecedented opportunities to use genetic analyses to elucidate animal ecology, behavior, and population structure without affecting the behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal sampled. Hair associated with an animal track in the snow, the shed exoskeleton of an insect, or a swab of animal scat are all examples of non-invasive methods to collect eDNA. Despite the seemingly uncomplicated definition of "non-invasive" as proposed by Taberlet et al. [1], Lefort et al. [2] highlight that its appropriate application to sampling methods in practice is not so straightforward. For example, collecting scat left behind on the forest floor by a mammal could be invasive if feces is used by that species to mark territorial boundaries. Other collection strategies such as baited DNA traps to collect hair, capturing and handling an individual to swab or stimulate emission of a body fluid, or removal of a presumed non essential body part like a feather, fish scale, or even a leg from an insect are often described as "non-invasive" sampling methods. However, such methods cannot be considered truly non-invasive. At a minimum, attracting or capturing and handling an animal to obtain a DNA sample interrupts its normal behavioral routine, but additionally can cause both acute and long-lasting physiological and behavioral stress responses and other effects. Even invertebrates exhibit long-term hypersensitization after an injury, which manifests as heightened vigilance and enhanced escape responses [3-5]. References [1] Taberlet P., Waits L. P. and Luikart G. 1999. Noninvasive genetic sampling: look before you leap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 323-327. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01637-7 | Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling | Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer | <p>The use of DNA data is ubiquitous across animal sciences. DNA may be obtained from an organism for a myriad of reasons including identification and distinction between cryptic species, sex identification, comparisons of different morphocryptic ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Molecular ecology, Zoology | Thomas Wilson Sappington | 2018-11-30 13:33:31 | View | |

14 May 2019

Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imagingMarie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches https://doi.org/10.1101/425561OB-GYN for salmon parrsRecommended by Jean-Olivier Irisson based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population dynamics and stock assessment models are only as good as the data used to parameterise them. For Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations, a critical parameter may be frequency of precocious maturation. Indeed, the young males (parrs) that mature early, before leaving the river to reach the ocean, can contribute to reproduction but have much lower survival rates afterwards. The authors cite evidence of the potentially major consequences of this alternate reproductive strategy. So, to be parameterised correctly, it needs to be assessed correctly. Cue the ultrasound machine. Through a thorough analysis of data collected on 850 individuals [1], over three years, the authors clearly show that the non-invasive examination of the internal cavity of young fishes to look for gonads, using a portable ultrasound machine, provides reliable and replicable evidence of precocious maturation. They turned into OB-GYN for salmons (albeit for male salmons!) and it worked. While using ultrasounds to detect fish gonads is not a new idea (early attempts for salmonids date back to the 80s [2]), the value here is in the comparison with the classic visual inspection technique (which turns out to be less reliable) and the fact that ultrasounds can now easily be carried out in the field. Beyond the potentially important consequences of this new technique for the correct assessment of salmon population dynamics, the authors also make the case for the acquisition of more reliable individual-level data in ecological studies, which I applaud. References. [1] Nevoux M, Marchand F, Forget G, Huteau D, Tremblay J, and Destouches J-P. (2019). Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging. bioRxiv 425561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/425561 | Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging | Marie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches | <p>Salmonids are characterized by a large diversity of life histories, but their study is often limited by the imperfect observation of the true state of an individual in the wild. Challenged by the need to reduce uncertainty of empirical data, re... | Conservation biology, Demography, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Jean-Olivier Irisson | 2018-09-25 17:24:59 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle