Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Sep 2019

Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA samplingMarie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/385120Words matter: extensive misapplication of "non-invasive" in describing DNA sampling methods, and proposed clarifying termsRecommended by Thomas Wilson Sappington based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe ability to successfully sequence trace quantities of environmental DNA (eDNA) has provided unprecedented opportunities to use genetic analyses to elucidate animal ecology, behavior, and population structure without affecting the behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal sampled. Hair associated with an animal track in the snow, the shed exoskeleton of an insect, or a swab of animal scat are all examples of non-invasive methods to collect eDNA. Despite the seemingly uncomplicated definition of "non-invasive" as proposed by Taberlet et al. [1], Lefort et al. [2] highlight that its appropriate application to sampling methods in practice is not so straightforward. For example, collecting scat left behind on the forest floor by a mammal could be invasive if feces is used by that species to mark territorial boundaries. Other collection strategies such as baited DNA traps to collect hair, capturing and handling an individual to swab or stimulate emission of a body fluid, or removal of a presumed non essential body part like a feather, fish scale, or even a leg from an insect are often described as "non-invasive" sampling methods. However, such methods cannot be considered truly non-invasive. At a minimum, attracting or capturing and handling an animal to obtain a DNA sample interrupts its normal behavioral routine, but additionally can cause both acute and long-lasting physiological and behavioral stress responses and other effects. Even invertebrates exhibit long-term hypersensitization after an injury, which manifests as heightened vigilance and enhanced escape responses [3-5]. References [1] Taberlet P., Waits L. P. and Luikart G. 1999. Noninvasive genetic sampling: look before you leap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 323-327. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01637-7 | Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling | Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer | <p>The use of DNA data is ubiquitous across animal sciences. DNA may be obtained from an organism for a myriad of reasons including identification and distinction between cryptic species, sex identification, comparisons of different morphocryptic ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Molecular ecology, Zoology | Thomas Wilson Sappington | 2018-11-30 13:33:31 | View | |

24 Mar 2023

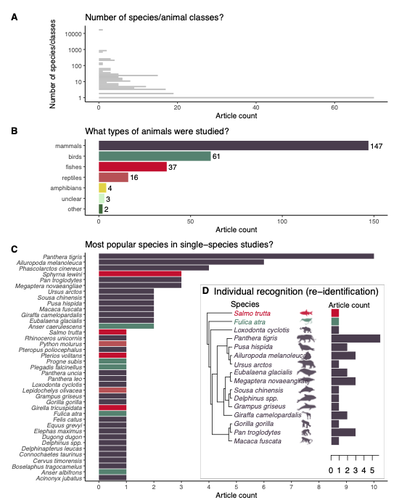

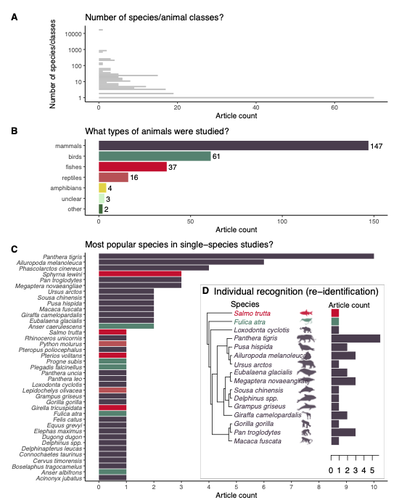

Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imageryShinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59DReview of machine learning uses for the analysis of images on wildlifeRecommended by Olivier Gimenez based on reviews by Falk Huettmann and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the field of ecology, there is a growing interest in machine (including deep) learning for processing and automatizing repetitive analyses on large amounts of images collected from camera traps, drones and smartphones, among others. These analyses include species or individual recognition and classification, counting or tracking individuals, detecting and classifying behavior. By saving countless times of manual work and tapping into massive amounts of data that keep accumulating with technological advances, machine learning is becoming an essential tool for ecologists. We refer to recent papers for more details on machine learning for ecology and evolution (Besson et al. 2022, Borowiec et al. 2022, Christin et al. 2019, Goodwin et al. 2022, Lamba et al. 2019, Nazir & Kaleem 2021, Perry et al. 2022, Picher & Hartig 2023, Tuia et al. 2022, Wäldchen & Mäder 2018). In their paper, Nakagawa et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of the literature on machine learning for wildlife imagery. Interestingly, the authors used a method unfamiliar to ecologists but well-established in medicine called rapid review, which has the advantage of being quickly completed compared to a fully comprehensive systematic review while being representative (Lagisz et al., 2022). Through a rigorous examination of more than 200 articles, the authors identified trends and gaps, and provided suggestions for future work. Listing all their findings would be counterproductive (you’d better read the paper), and I will focus on a few results that I have found striking, fully assuming a biased reading of the paper. First, Nakagawa et al. (2023) found that most articles used neural networks to analyze images, in general through collaboration with computer scientists. A challenge here is probably to think of teaching computer vision to the generations of ecologists to come (Cole et al. 2023). Second, the images were dominantly collected from camera traps, with an increase in the use of aerial images from drones/aircrafts that raise specific challenges. Third, the species concerned were mostly mammals and birds, suggesting that future applications should aim to mitigate this taxonomic bias, by including, e.g., invertebrate species. Fourth, most papers were written by authors affiliated with three countries (Australia, China, and the USA) while India and African countries provided lots of images, likely an example of scientific colonialism which should be tackled by e.g., capacity building and the involvement of local collaborators. Last, few studies shared their code and data, which obviously impedes reproducibility. Hopefully, with the journals’ policy of mandatory sharing of codes and data, this trend will be reversed. REFERENCES Besson M, Alison J, Bjerge K, Gorochowski TE, Høye TT, Jucker T, Mann HMR, Clements CF (2022) Towards the fully automated monitoring of ecological communities. Ecology Letters, 25, 2753–2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14123 Borowiec ML, Dikow RB, Frandsen PB, McKeeken A, Valentini G, White AE (2022) Deep learning as a tool for ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1640–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13901 Christin S, Hervet É, Lecomte N (2019) Applications for deep learning in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13256 Cole E, Stathatos S, Lütjens B, Sharma T, Kay J, Parham J, Kellenberger B, Beery S (2023) Teaching Computer Vision for Ecology. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.02211 Goodwin M, Halvorsen KT, Jiao L, Knausgård KM, Martin AH, Moyano M, Oomen RA, Rasmussen JH, Sørdalen TK, Thorbjørnsen SH (2022) Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: overview, applications, and outlook†. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255 Lagisz M, Vasilakopoulou K, Bridge C, Santamouris M, Nakagawa S (2022) Rapid systematic reviews for synthesizing research on built environment. Environmental Development, 43, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100730 Lamba A, Cassey P, Segaran RR, Koh LP (2019) Deep learning for environmental conservation. Current Biology, 29, R977–R982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.016 Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Francis R, Tam J, Li X, Elphinstone A, Jordan N, O’Brien J, Pitcher B, Sluys MV, Sowmya A, Kingsford R (2023) Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59D Nazir S, Kaleem M (2021) Advances in image acquisition and processing technologies transforming animal ecological studies. Ecological Informatics, 61, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101212 Perry GLW, Seidl R, Bellvé AM, Rammer W (2022) An Outlook for Deep Learning in Ecosystem Science. Ecosystems, 25, 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y Pichler M, Hartig F Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14061 Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, Risse B, Mathis A, Mathis MW, van Langevelde F, Burghardt T, Kays R, Klinck H, Wikelski M, Couzin ID, van Horn G, Crofoot MC, Stewart CV, Berger-Wolf T (2022) Perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. Nature Communications, 13, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27980-y Wäldchen J, Mäder P (2018) Machine learning for image-based species identification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13075 | Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery | Shinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford | <p>1. Machine (especially deep) learning algorithms are changing the way wildlife imagery is processed. They dramatically speed up the time to detect, count, classify animals and their behaviours. Yet, we currently have a very few systematic liter... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology | Olivier Gimenez | Anonymous | 2022-10-31 22:05:46 | View |

13 May 2024

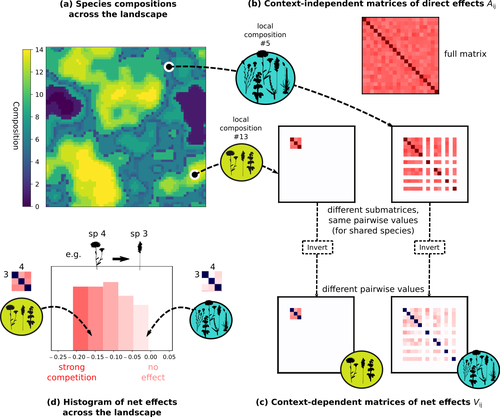

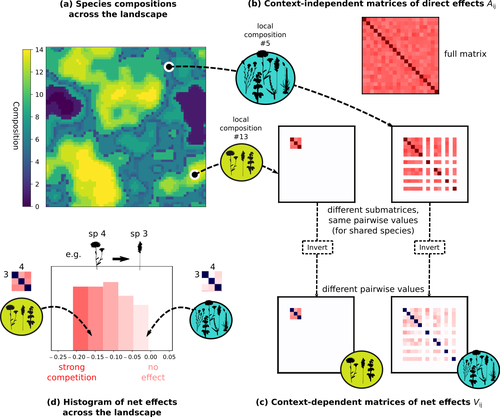

Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in MetacommunitiesMatthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.04.543606Beyond pairwise species interactions: coarser inference of their joined effects is more relevantRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler

Barbier et al. (2024) investigated the dynamics of species abundances depending on their ecological niche (abiotic component) and on (numerous) competitive interactions. In line with previous evidence and expectations (Barbier et al. 2018), the authors show that it is possible to robustly infer the mean and variance of interaction coefficients from species co-distributions, while it is not possible to infer the individual coefficient values. The authors devised a simulation framework representing multispecies dynamics in an heterogeneous environmental context (2D grid landscape). They used a Lotka-Volterra framework involving pairwise interaction coefficients and species-specific carrying capacities. These capacities depend on how well the species niche matches the local environmental conditions, through a Gaussian function of the distance of the species niche centers to the local environmental values. They considered two contrasted scenarios denoted as « Environmental tracking » and « Dispersal limited ». In the latter case, species are initially seeded over the environmental grid and cannot disperse to other cells, while in the former case they can disperse and possibly be more performant in other cells. The direct effects of species on one another are encoded in an interaction matrix A, and the authors further considered net interactions depending on the inverse of the matrix of direct interactions (Zelnik et al., 2024). The net effects are context-dependent, i.e., it involves the environment-dependent biotic capacities, even through the interaction terms can be defined between species as independent from local environment. The results presented here underline that the outcome of many individual competitive interactions can only be understood in terms of macroscopic properties. In essence, the results here echoe the mean field theories that investigate the dynamics of average ecological properties instead of the microscopic components (e.g., McKane et al. 2000). In a philosophical perspective, community ecology has long struggled with analyzing and inferring local determinants of species coexistence from species co-occurrence patterns, so that it was claimed that no universal laws can be derived in the discipline (Lawton 1999). Using different and complementary methods and perspectives, recent research has also shown that species assembly parameter values cannot be unambiguously inferred from species co-occurrences only, even in simple designs where an equilibrium can be reached (Poggiato et al. 2021). Although the roles of high-order competitive interactions and intransivity can lead to species coexistence, the simple view of a single loop of competitive interactions is easily challenged when further interactions and complexity is added (Gallien et al. 2024). But should we put so much emphasis on inferring individual interaction coefficients? In a quest to understand the emerging properties of elementary processes, ecological theory could go forward with a more macroscopic analysis and understanding of species coexistence in many communities. The authors referred several times to an interesting paper from Schaffer (1981), entitled « Ecological abstraction: the consequences of reduced dimensionality in ecological models ». It proposes that estimating individual species competition coefficients is not possible, but that competition can be assessed at the coarser level of organisation, i.e., between ecological guilds. This idea implies that the dimensionality of the competition equations should be greatly reduced to become tractable in practice. Taking together this claim with the results of the present Barbier et al. (2024) paper, it becomes clearer that the nature of competitive interactions can be addressed through « abstracted » quantities, as those of guilds or the moments of the individual competition coefficients (here the average and the standard deviation). Therefore the scope of Barbier et al. (2024) framework goes beyond statistical issues in parameter inference, but question the way we must think and represent the numerous competitive interactions in a simplified and robust way. References Barbier, Matthieu, Jean-François Arnoldi, Guy Bunin, et Michel Loreau. 2018. « Generic assembly patterns in complex ecological communities ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9): 2156‑61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710352115 | Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in Metacommunities | Matthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold | <p>AbstractOne of the more difficult challenges in community ecology is inferring species interactions on the basis of patterns in the spatial distribution of organisms. At its core, the problem is that distributional patterns reflect the ‘realize... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Competition, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2023-10-21 14:14:16 | View | |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

13 Jul 2023

Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predatorsLoïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552Indirect effects of parasitism include increased profitability of prey to optimal foragersRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Thierry DE MEEUS and Eglantine Mathieu-BégnéEven though all living organisms are, at the same time, involved in host-parasite interactions and embedded in complex food webs, the indirect effects of parasitism are only beginning to be unveiled. Prosnier et al. investigated the direct and indirect effects of parasitism making use of a very interesting biological system comprising the freshwater zooplankton Daphnia magna and its highly specific parasite, the iridovirus DIV-1 (Daphnia-iridescent virus 1). Daphnia are typically semitransparent, but once infected develop a white phenotype with a characteristic iridescent shine due to the enlargement of white fat cells. In a combination of infection trials and comparison of white and non-white phenotypes collected in natural ponds, the authors demonstrated increased mortality and reduced lifetime fitness in infected Daphnia. Furthermore, white phenotypes had lower mobility, increased reflectance, larger body sizes and higher protein content than non-white phenotypes. As a consequence, total energy content was effectively doubled in white Daphnia when compared to non-white broodless Daphnia. Next the authors conducted foraging trials with Daphnia predators Notonecta (the backswimmer) and Phoxinus (the European minnow). Focusing on Notonecta, unchanged search time and increased handling time were more than compensated by the increased energy content of white Daphnia. White Daphnia were 24% more profitable and consistently preferred by Notonecta, as the optimal foraging theory would predict. The authors argue that menu decisions of optimal foragers in the field might be different, however, as the prevalence – and therefore availability - of white phenotypes in natural populations is very low. The study therefore contributes to our understanding of the trophic context of parasitism. One shortcoming of the study is that the authors rely exclusively on phenotypic signs for determining infection. On their side, DIV-1 is currently known to be highly specific to Daphnia, their study site is well within DIV-1 distributional range, and the symptoms of infection are very conspicuous. Furthermore, the infection trial – in which non-white Daphnia were exposed to white Daphnia homogenates - effectively caused several lethal and sublethal effects associated with DIV-1 infection, including iridescence. However, the infection trial also demonstrated that part of the exposed individuals developed intermediate traits while still keeping the non-white, non-iridescent phenotype. Thus, there may be more subtleties to the association of DIV-1 infection of Daphnia with ecological and evolutionary consequences, such as costs to resistance or covert infection, that the authors acknowledge, and that would be benefitted by coupling experimental and observational studies with the determination of actual infection and viral loads. References Prosnier L., N. Loeuille, F.D. Hulot, D. Renault, C. Piscart, B. Bicocchi, M, Deparis, M. Lam, & V. Médoc. (2023). Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552 | Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators | Loïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc | <p>Parasites are omnipresent, and their eco-evolutionary significance has aroused much interest from scientists. Parasites may affect their hosts in many ways by altering host density, vulnerability to predation, and energy content, thus modifying... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Epidemiology, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Life history, Parasitology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2022-05-20 10:15:41 | View | |

30 Mar 2020

Environmental variables determining the distribution of an avian parasite: the case of the Philornis torquans complex (Diptera: Muscidae) in South AmericaPablo F. Cuervo, Alejandro Percara, Lucas Monje, Pablo M. Beldomenico, Martín A. Quiroga https://doi.org/10.1101/839589Catching the fly in dystopian timesRecommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersHost-parasite interactions are ubiquitous on Earth. They are present in almost every conceivable ecosystem and often result from a long history of antagonist coevolution [1,2]. Recent studies on climate change have revealed, however, that modification of abiotic variables are often accompanied by shifts in the distributional range of parasites to habitats far beyond their original geographical distribution, creating new interactions in novel habitats with unpredictable consequences for host community structure and organization [3,4]. This situation may be especially critical for endangered host species having small population abundance and restricted distribution range. The infestation of bird species with larvae of the muscid fly genus Philornis is a case in point. At least 250 bird species inhabiting mostly Central and South America are infected by Philornis flies [5,6]. Fly larval development occurs in bird faeces, nesting material, or inside nestlings, affecting the development and nestling survival. References [1] Thompson JN (1994) The Coevolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press. | Environmental variables determining the distribution of an avian parasite: the case of the Philornis torquans complex (Diptera: Muscidae) in South America | Pablo F. Cuervo, Alejandro Percara, Lucas Monje, Pablo M. Beldomenico, Martín A. Quiroga | <p>*Philornis* flies are the major cause of myasis in altricial nestlings of neotropical birds. Its impact ranges from subtle to lethal, being of major concern in endangered bird species with geographically-restricted, fragmented and small-sized p... |  | Biogeography, Macroecology, Parasitology, Species distributions | Rodrigo Medel | 2019-11-26 21:31:33 | View | |

28 Sep 2020

The dynamics of spawning acts by a semelparous fish and its associated energetic costsCédric Tentelier, Colin Bouchard, Anaïs Bernardin, Amandine Tauzin, Jean-Christophe Aymes, Frédéric Lange, Charlotte Recapet, Jacques Rives https://doi.org/10.1101/436295Extreme weight loss: when accelerometer could reveal reproductive investment in a semelparous fish speciesRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison, Loïc Teulier and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison, Loïc Teulier and 1 anonymous reviewer

Continuous observation of animal behaviour could be quite a challenge in the field, and the situation becomes even more complicated with aquatic species mostly active at night. In such cases, biologging techniques are real game changers in ecology, behavioural ecology or eco-physiology. An accelerating number of methodological applications of these tools in natural condition are thus published each year [1]. Biologging is not limited to movement ecology. For instance, fine grain information about energy expenditure can be inferred from body acceleration [2], and accelerometers has already proven useful in monitoring reproductive costs in some fish species [3,4]. The first part of the study by Tentelier et al. [5] is in line with this growing literature. It describes measurements of energy expenditure during reproduction in a fish species, Allis shad (Alosa Alosa), based on tail beat frequency and occurrence of spawning acts. The study has been convincingly conducted, and the results are important for fish biologists. But this is not the whole story: the authors added to this otherwise classical study a very original and insightful analysis which deserves closer interest. References [1] Börger L, Bijleveld AI, Fayet AL, Machovsky‐Capuska GE, Patrick SC, Street GM and Vander Wal E. (2020) Biologging special feature. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 6–15. 10.1111/1365-2656.13163 | The dynamics of spawning acts by a semelparous fish and its associated energetic costs | Cédric Tentelier, Colin Bouchard, Anaïs Bernardin, Amandine Tauzin, Jean-Christophe Aymes, Frédéric Lange, Charlotte Recapet, Jacques Rives | <p>1. During the reproductive season, animals have to manage both their energetic budget and gamete stock. In particular, for semelparous capital breeders with determinate fecundity and no parental care other than gametic investment, the depletion... | Behaviour & Ethology, Freshwater ecology, Life history | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2020-06-04 15:18:56 | View | ||

22 Mar 2021

Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore speciesBastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544Plants preserve the ghost of competition past for herbivores, but mothers don’t careRecommended by Sara Magalhães based on reviews by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-PereiraSome biological hypotheses are widely popular, so much so that we tend to forget their original lack of success. This is particularly true for hypotheses with catchy names. The ‘Ghost of competition past’ is part of the title of a paper by the great ecologist, JH Connell, one of the many losses of 2020 (Connell 1980). The hypothesis states that, even though we may not detect competition in current populations, their traits and distributions may be shaped by past competition events. Although this hypothesis has known a great success in the ecological literature, the original paper actually ends with “I will no longer be persuaded by such invoking of "the Ghost of Competition Past"”. Similarly, the hypothesis that mothers of herbivores choose host plants where their offspring will have a higher fitness was proposed by John Jaenike in 1978 (Jaenike 1978), and later coined the ‘mother knows best’ hypothesis. The hypothesis was readily questioned or dismissed: “Mother doesn't know best” (Courtney and Kibota 1990), or “Does mother know best?” (Valladares and Lawton 1991), but remains widely popular. It thus seems that catchy names (and the intuitive ideas behind them) have a heuristic value that is independent from the original persuasion in these ideas and the accumulation of evidence that followed it. The paper by Castagneryol et al. (2021) analyses the preference-performance relationship in the box tree moth (BTM) Cydalima perspectalis, after defoliation of their host plant, the box tree, by conspecifics. It thus has bearings on the two previously mentioned hypotheses. Specifically, they created an artificial population of potted box trees in a greenhouse, in which 60 trees were infested with BTM third instar larvae, whereas 61 were left uninfested. One week later, these larvae were removed and another three weeks later, they released adult BTM females and recorded their host choice by counting egg clutches laid by these females on the plants. Finally, they evaluated the effect of previously infested vs uninfested plants on BTM performance by measuring the weight of third instar larvae that had emerged from those eggs. This experimental design was adopted because BTM is a multivoltine species. When the second generation of BTM arrives, plants have been defoliated by the first generation and did not fully recover. Indeed, Castagneryol et al. (2021) found that larvae that developed on previously infested plants were much smaller than those developing on uninfested plants, and the same was true for the chrysalis that emerged from those larvae. This provides unequivocal evidence for the existence of a ghost of competition past in this system. However, the existence of this ghost still does not result in a change in the distribution of BTM, precisely because mothers do not know best: they lay as many eggs on plants previously infested than on uninfested plants. The demonstration that the previous presence of a competitor affects the performance of this herbivore species confirms that ghosts exist. However, whether this entails that previous (interspecific) competition shapes species distributions, as originally meant, remains an open question. Species phenology may play an important role in exposing organisms to the ghost, as this time-lagged competition may have been often overlooked. It is also relevant to try to understand why mothers don’t care in this, and other systems. One possibility is that they will have few opportunities to effectively choose in the real world, due to limited dispersal or to all plants being previously infested. References Castagneyrol, B., Halder, I. van, Kadiri, Y., Schillé, L. and Jactel, H. (2021) Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.228544, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544 Connell, J. H. (1980). Diversity and the coevolution of competitors, or the ghost of competition past. Oikos, 131-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 Courtney, S. P. and Kibota, T. T. (1990) in Insect-plant interactions (ed. Bernays, E.A.) 285-330. Jaenike, J. (1978). On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects. Theoretical population biology, 14(3), 350-356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6 Valladares, G., and Lawton, J. H. (1991). Host-plant selection in the holly leaf-miner: does mother know best?. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 227-240. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/5456

| Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species | Bastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel | <p>Conspecific insect herbivores co-occurring on the same host plant interact both directly through interference competition and indirectly through exploitative competition, plant-mediated interactions and enemy-mediated interactions. However, the... |  | Competition, Herbivory, Zoology | Sara Magalhães | 2020-08-03 15:50:23 | View | |

15 May 2023

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new contextLogan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xsAn experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativenessRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer

Whether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014). Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027 Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019) Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs | Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context | Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. Howev... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-01-13 19:08:52 | View | ||

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle