Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

17 May 2023

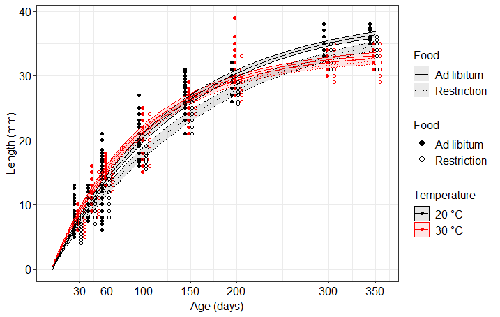

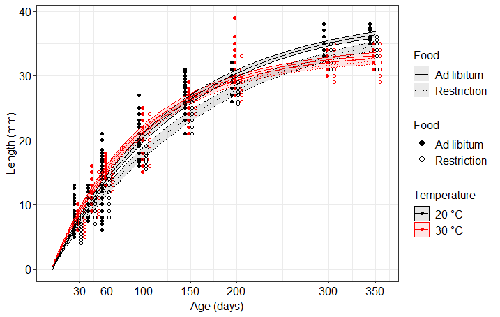

Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectothermsSimon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3Effect of food conditions on the Temperature-Size RuleRecommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Wilco VerberkTemperature-size rule (TSR) is a phenomenon of plastic changes in body size in response to temperature, originally observed in more than 80% of ectothermic organisms representing various groups (Atkinson 1994). In particular, ectotherms were observed to grow faster and reach smaller size at higher temperature and grow slower and achieve larger size at lower temperature. This response has fired the imagination of researchers since its invention, due to its counterintuitive pattern from an evolutionary perspective (Berrigan and Charnov 1994). The main question to be resolved is: why do organisms grow fast and achieve smaller sizes under more favourable conditions (= relatively higher temperature), while they grow longer and achieve larger sizes under less favourable conditions (relatively lower temperature), if larger size means higher fitness, while longer development may be risky? This evolutionary conundrum still awaits an ultimate explanation (Angilletta Jr et al. 2004; Angilletta and Dunham 2003; Verberk et al. 2021). Although theoretical modelling has shown that such a growth pattern can be achieved as a response to temperature alone, with a specific combination of energetic parameters and external mortality (Kozłowski et al. 2004), it has been suggested that other temperature-dependent environmental variables may be the actual drivers of this pattern. One of the most frequently invoked variable is the relative oxygen availability in the environment (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2006; Audzijonyte et al. 2019; Verberk et al. 2021; Woods 1999), which decreases with temperature increase. Importantly, this effect is more pronounced in aquatic systems (Forster et al. 2012). However, other temperature-dependent parameters are also being examined in the context of their possible effect on TSR induction and strength. Food availability is among the interfering factors in this regard. In aquatic systems, nutritional conditions are generally better at higher temperature, while a range of relatively mild thermal conditions is considered. However, there are no conclusive results so far on how nutritional conditions affect the plastic body size response to acute temperature changes. A study by Bazin et al. (2023) examined this particular issue, the effects of food and temperature on TSR, in medaka fish. An important value of the study was to relate the patterns found to fitness. This is a rare and highly desirable approach since evolutionary significance of any results cannot be reliably interpreted unless shown as expressed in light of fitness. The authors compared the body size of fish kept at 20°C and 30°C under conditions of food abundance or food restriction. The results showed that the TSR (smaller body size at 30°C compared to 20°C) was observed in both food treatments, but the effect was delayed during fish development under food restriction. Regarding the relevance to fitness, increased temperature resulted in more eggs laid but higher mortality, while food restriction increased survival but decreased the number of eggs laid in both thermal treatments. Overall, food restriction seemed to have a more severe effect on development at 20°C than at 30°C, contrary to the authors’ expectations. I found this result particularly interesting. One possible interpretation, also suggested by the authors, is that the relative oxygen availability, which was not controlled for in this study, could have affected this pattern. According to theoretical predictions confirmed in quite many empirical studies so far, oxygen restriction is more severe at higher temperatures. Perhaps for these particular two thermal treatments and in the case of the particular species studied, this restriction was more severe for organismal performance than the food restriction. This result is an example that all three variables, temperature, food and oxygen, should be taken into account in future studies if the interrelationship between them is to be understood in the context of TSR. It also shows that the reasons for growing smaller in warm may be different from those for growing larger in cold, as suggested, directly or indirectly, in some previous studies (Hessen et al. 2010; Leiva et al. 2019). Since medaka fish represent predatory vertebrates, the results of the study contribute to the issue of global warming effect on food webs, as the authors rightly point out. This is an important issue because the general decrease in the size or organisms in the aquatic environment with global warming is a fact (e.g., Daufresne et al. 2009), while the question of how this might affect entire communities is not trivial to resolve (Ohlberger 2013). REFERENCES Angilletta Jr, M. J., T. D. Steury & M. W. Sears, 2004. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life–history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44:498-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498 Angilletta, M. J. & A. E. Dunham, 2003. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: Simple evolutionary explanations may not be general. American Naturalist 162(3):332-342. https://doi.org/10.1086/377187 Atkinson, D., 1994. Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms. Advances in Ecological Research 25:1-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3 Atkinson, D., S. A. Morley & R. N. Hughes, 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply? Evolution & Development 8(2):202-214 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x Audzijonyte, A., D. R. Barneche, A. R. Baudron, J. Belmaker, T. D. Clark, C. T. Marshall, J. R. Morrongiello & I. van Rijn, 2019. Is oxygen limitation in warming waters a valid mechanism to explain decreased body sizes in aquatic ectotherms? Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(2):64-77 https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12847 Bazin, S., Hemmer-Brepson, C., Logez, M., Sentis, A. & Daufresne, M. 2023. Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms. HAL, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3 Berrigan, D. & E. L. Charnov, 1994. Reaction norms for age and size at maturity in response to temperature – a puzzle for life historians. Oikos 70:474-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545787 Daufresne, M., K. Lengfellner & U. Sommer, 2009. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106(31):12788-93 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902080106 Forster, J., A. G. Hirst & D. Atkinson, 2012. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(47):19310-19314. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210460109 Hessen, D. O., P. D. Jeyasingh, M. Neiman & L. J. Weider, 2010. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004 Kozłowski, J., M. Czarnoleski & M. Dańko, 2004. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold? Integrative and Comparative Biology 44(6):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.480 Leiva, F. P., P. Calosi & W. C. E. P. Verberk, 2019. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374:20190035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0035 Ohlberger, J., 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body szie - from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12098 Verberk, W. C. E. P., D. Atkinson, K. N. Hoefnagel, A. G. Hirst, C. R. Horne & H. Siepel, 2021. Shrinking body sizes in response to warming: explanations for the temperature-size rule with special emphasis on the role of oxygen. Biological Reviews 96:247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12653 Woods, H. A., 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. American Zoologist 39:244-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.2.244 | Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms | Simon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne | <p>The reduction of body size with warming has been proposed as the third universal response to global warming, besides geographical and phenological shifts. Observed body size shifts in ectotherms are mostly attributed to the temperature size rul... |  | Climate change, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2022-07-27 09:28:29 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora coralsK. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza https://doi.org/10.1101/398602Transcriptomics of thermal stress response in coralsRecommended by Staffan Jacob based on reviews by Mar SobralClimate change presents a challenge to many life forms and the resulting loss of biodiversity will critically depend on the ability of organisms to timely respond to a changing environment. Shifts in ecological parameters have repeatedly been attributed to global warming, with the effectiveness of these responses varying among species [1, 2]. Organisms do not only have to face a global increase in mean temperatures, but a complex interplay with another crucial but largely understudied aspect of climate change: thermal fluctuations. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adaptation to thermal fluctuations is thus a timely and critical challenge. References [1] Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286 | Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora corals | K. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza | <p>Ecosystems worldwide are suffering from climate change. Coral reef ecosystems are globally threatened by increasing sea surface temperatures. However, gene expression plasticity provides the potential for organisms to respond rapidly and effect... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Symbiosis | Staffan Jacob | 2018-08-29 10:46:55 | View | |

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View | |

05 Nov 2019

Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population.Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. https://doi.org/10.1101/474874Defoliation induces a trade-off between reproduction and growth in a southern population of BeechRecommended by Georges Kunstler based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIndividuals ability to withstand abiotic and biotic stresses is crucial to the maintenance of populations at climate edge of tree species distribution. We start to have a detailed understanding of tree growth response and to a lesser extent mortality response in these populations. In contrast, our understanding of the response of tree fecundity and recruitment remains limited because of the difficulty to monitor it at the individual tree level in the field. Tree recruitment limitation is, however, crucial for tree population dynamics [1-2]. References [1] Clark, J. S. et al. (1999). Interpreting recruitment limitation in forests. American Journal of Botany, 86(1), 1-16. doi: 10.2307/2656950 | Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population. | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. | <p>1. Although droughts and heatwaves have been associated to increased crown defoliation, decreased growth and a higher risk of mortality in many forest tree species, their impact on tree reproduction and forest regeneration still remains underst... |  | Climate change, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Molecular ecology, Physiology, Population ecology | Georges Kunstler | 2018-11-20 13:29:42 | View | |

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

02 Jun 2021

Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populationsOlivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.28.428563Blue tits surviving in an ever-changing worldRecommended by Dieter Lukas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas

How long individuals live has a large influence on a number of biological processes, both for the individuals themselves as well as for the populations they live in. For a given species, survival is often summarized in curves showing the probability to survive from one age to the next. However, these curves often hide a large amount of variation in survival. Variation can occur from chance, or if individuals have different genotypes or phenotypes that can influence how long they might live, or if environmental conditions are not the same across time or space. Such spatiotemporal variations in the conditions that individuals experience can lead to complex patterns of evolution (Kokko et al. 2017) but because of the difficulties to obtain the relevant data they have not been studied much in natural populations. Charmantier A, Doutrelant C, Dubuc-Messier G, Fargevieille A, Szulkin M (2016) Mediterranean blue tits as a case study of local adaptation. Evolutionary Applications, 9, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12282 Dubuc-Messier G, Réale D, Perret P, Charmantier A (2017) Environmental heterogeneity and population differences in blue tits personality traits. Behavioral Ecology, 28, 448–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arw148 Kokko H, Chaturvedi A, Croll D, Fischer MC, Guillaume F, Karrenberg S, Kerr B, Rolshausen G, Stapley J (2017) Can Evolution Supply What Ecology Demands? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.12.005 Lewontin RC, Cohen D (1969) On Population Growth in a Randomly Varying Environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 62, 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.62.4.1056 | Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populations | Olivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">In a context of rapid climate change, the influence of large-scale and local climate on population demography is increasingly scrutinized, yet studies are usually focused on one population. Demographic parameters, i... |  | Climate change, Demography, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Population ecology | Dieter Lukas | 2021-01-29 15:24:23 | View | |

29 Jan 2020

Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stabilityArnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya https://doi.org/10.1101/589895On the importance of stoichiometric constraints for understanding global change effects on food web dynamicsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe constraints associated with the mass balance of chemical elements (i.e. stoichiometric constraints) are critical to our understanding of ecological interactions, as outlined by the ecological stoichiometry theory [1]. Species in ecosystems differ in their elemental composition as well as in their level of elemental homeostasis [2], which can determine the outcome of interactions such as herbivory or decomposition on species coexistence and ecosystem functioning [3, 4]. References [1] Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J. (2017). Ecological Stoichiometry, The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. doi: 10.1515/9781400885695 | Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability | Arnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya | <p>Temperature and nutrients are two of the most important drivers of global change. Both can modify the elemental composition (i.e. stoichiometry) of primary producers and consumers. Yet their combined effect on the stoichiometry, dynamics, and s... |  | Climate change, Community ecology, Food webs, Theoretical ecology, Thermal ecology | Elisa Thebault | 2019-08-08 12:20:08 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snailKatja Leicht, Otto Seppälä https://doi.org/10.1101/449777Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snailsRecommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentisAmongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor. References [1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704 | Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail | Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä | <p>Global climate change imposes a serious threat to natural populations of many species. Estimates of the effects of climate change‐mediated environmental stresses are, however, often based only on their direct effects on organisms, and neglect t... |  | Climate change | vincent calcagno | 2018-10-22 22:19:22 | View | |

14 Dec 2018

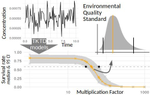

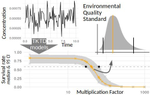

Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics modelsVirgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles https://doi.org/10.1101/356469Addressing uncertainty in Environmental Risk Assessment using mechanistic toxicological models coupled with Bayesian inferenceRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Andreas Focks and 2 anonymous reviewersEnvironmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a strategic conceptual framework to characterize the nature and magnitude of risks, to humans and biodiversity, of the release of chemical contaminants in the environment. Several measures have been suggested to enhance the science and application of ERA, including the identification and acknowledgment of uncertainties that potentially influence the outcome of risk assessments, and the appropriate consideration of temporal scale and its linkage to assessment endpoints [1]. References [1] Dale, V. H., Biddinger, G. R., Newman, M. C., Oris, J. T., Suter, G. W., Thompson, T., ... & Chapman, P. M. (2008). Enhancing the ecological risk assessment process. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 4(3), 306-313. doi: 10.1897/IEAM_2007-066.1 | Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models | Virgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles | <p>Providing reliable environmental quality standards (EQS) is a challenging issue for environmental risk assessment (ERA). These EQS are derived from toxicity endpoints estimated from dose-response models to identify and characterize the environm... |  | Chemical ecology, Ecotoxicology, Experimental ecology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2018-06-27 21:33:30 | View | |

11 Mar 2022

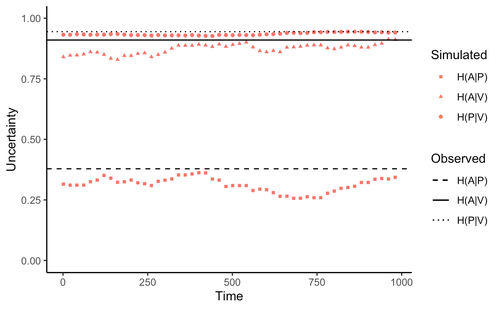

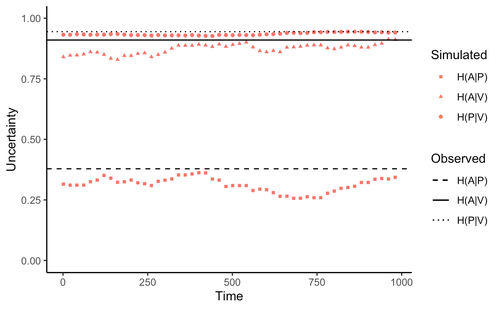

Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities”Ethan Bass, André Kessler https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/xsbtmDoes information theory inform chemical arms race communication?Recommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by Claudio Ramirez and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the long-standing questions in evolutionary ecology is on the mechanisms involved in arms race coevolution. One way to address this question is to understand the conditions under which one species evolves traits in response to the presence of a second species and so on. However, specialized pairwise interactions are by far less common in nature than interactions involving a higher number of interacting species (Bascompte, Jordano 2013). While interactions between large sets of species are the norm rather than the exception in mutualistic (pollination, seed dispersal), and antagonist (herbivory, parasitism) relationships, few is known on the way species identify, process, and respond to information provided by other interacting species under field conditions (Schaefer, Ruxton 2011). Zu et al. (2020) addressed this general question by developing an interesting information theory-based approach that hypothesized conditional entropy in chemical communication plays a role as proxy of fitness in plant-herbivore communities. More specifically, plant fitness was assumed to be related to the efficiency to code signals by plant species, and herbivore fitness to the capacity to decode plant signals. In this way, from the plant perspective, the elaboration of plant signals that elude decoding by herbivores is expected to be favored, as herbivores are expected to attack plants with simple chemical signals. The empirical observation upon which the model was tested was the redundancy in volatile organic compounds (VOC) found across plant species in a plant-herbivore community. Interestingly, Zu et al.’s model predicted successfully that VOC redundancy in the plant community associates with increased conditional entropy, which conveys herbivore confusion and plant protection against herbivory. In this way, plant species that evolve VOCs already present in the community might be benefitted, ultimately leading to the patterns of VOC redundancy commonly observed in nature. Bass & Kessler performed a series of interesting observations on Zu et al. (2020), that can be organized along three lines of reasoning. First, from an evolutionary perspective, Bass & Kessler note the important point that accepting that conditional information entropy, estimated from the contribution of every plant species to volatile redundancy implies that average plant fitness seems to depend on community-level properties (i.e., what the other species in the community are doing) rather than on population-level characteristics (I.e., what the individuals belonging a population are doing). While the level at which selection acts upon is a longstanding debate (e.g., Goodnight, 1990; Williams, 1992), the model seems to contradict one of the basic tenets of Darwinian evolution. The extent to which this important observation invalidates the contribution of Zu et al. (2020) is open to scrutiny. However, one can indulge the evolutionary criticism by arguing that every theoretical model performs a number of assumptions to preserve the simplicity of analyses. Furthermore, even accepting the criticism, the overall information-based framework is valuable as it provides a fresh perspective to the way coding and decoding chemical information in plant-herbivore interactions may result in arm race coevolution. The question to be assessed by members of the scientific community is how strong the evolutionary assumptions are to be acceptable. A second line of reasoning involves consideration of additional routes of chemical information transfer. If chemical volatiles are involved in another ecological function unrelated to arm race (as they are) such as toxicity, crypsis, aposematism, etc., the conditional information indices considered as proxy to plant and herbivore fitness may be only secondarily related to arms race. This is an interesting observation, which suggests that VOC production may have more than one ecological function, as it often happens in “pleiotropic” traits (Strauss, Irwin 2004). This is an exciting avenue for future research. Finally, a third category of comments involves the relationship between conditional information entropy and plant and herbivore fitness. Bass & Kessler developed a Bayesian treatment of the community-level information developed by Zu et al. (2020) that permitted to estimate fitness on a species rather than community level. Their results revealed that community conditional entropies fail to align with species-level indices, suggesting that conclusions of Strauss & Irwin (2004) are not commensurate with fitness at the species level, where the analysis seems to be pertinent. In general, I strongly recommend Bass & Kessler’s contribution as it provides a series of observations and new perspectives to Zu et al. (2020). Rather than restricting their manuscript to blind criticisms, Bass & Kessler provides new interesting perspectives, which is always welcome as it improves the value and scope of the original work. References Bascompte J, Jordano P (2013) Mutualistic Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691131269.001.0001 Bass E, Kessler A (2022) Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities.” EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/xsbtm Goodnight CJ (1990) Experimental Studies of Community Evolution I: The Response to Selection at the Community Level. Evolution, 44, 1614–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03850.x Schaefer HM, Ruxton GD (2011) Plant-Animal Communication. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199563609.001.0001 Strauss SY, Irwin RE (2004) Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Multispecies Plant-Animal Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 435–466. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130215 Williams GC (1992) Natural Selection: Domains, Levels, and Challenges. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. Zu P, Boege K, del-Val E, Schuman MC, Stevenson PC, Zaldivar-Riverón A, Saavedra S (2020) Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities. Science, 368, 1377–1381. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba2965 | Comment on “Information arms race explains plant-herbivore chemical communication in ecological communities” | Ethan Bass, André Kessler | <p style="text-align: justify;">Zu et al (Science, 19 Jun 2020, p. 1377) propose that an ‘information arms-race’ between plants and herbivores explains plant-herbivore communication at the community level. However, the analysis presented here show... |  | Chemical ecology, Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Rodrigo Medel | 2021-10-02 06:06:07 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle