Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▼ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

27 Nov 2023

Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted TreesWilliam Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443Gradient Boosted Trees can deliver more than accurate ecological predictionsRecommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne diseases are an important burden on public health all over the globe, making accurate forecasts of tick population a key ingredient in a successful public health strategy. Over long time scales, tick populations can undergo complex dynamics, as they are sensitive to many non-linear effects due to the complex relationships between ticks and the relevant (numerical) features of their environment. But luckily, capturing complex non-linear responses is a task that machine learning thrives on. In this contribution, Manley et al. (2023) explore the use of Gradient Boosted Trees to predict the distribution (presence/absence) and abundance of ticks across New York state. This is an interesting modelling challenge in and of itself, as it looks at the same ecological question as an instance of a classification problem (presence/absence) or of a regression problem (abundance). In using the same family of algorithm for both, Manley et al. (2023) provide an interesting showcase of the versatility of these techniques. But their article goes one step further, by setting up a multi-class categorical model that estimates jointly the presence and abundance of a population. I found this part of the article particularly elegant, as it provides an intermediate modelling strategy, in between having two disconnected models for distribution and abundance, and having nested models where abundance is only predicted for the present class (see e.g. Boulangeat et al., 2012, for a great description of the later). One thing that Manley et al. (2023) should be commended for is their focus on opening up the black box of machine learning techniques. I have never believed that ML models are more inherently opaque than other families of models, but the focus in this article on explainable machine learning shows how these models might, in fact, bring us closer to a phenomenological understanding of the mechanisms underpinning our observations. There is also an interesting discussion in this article, on the rate of false negatives in the different models that are being benchmarked. Although model selection often comes down to optimizing the overall quality of the confusion matrix (for distribution models, anyway), depending on the type of information we seek to extract from the model, not all types of errors are created equal. If the purpose of the model is to guide actions to control vectors of human pathogens, a false negative (predicting that the vector is absent at a site where it is actually present) is a potentially more damaging outcome, as it can lead to the vector population (and therefore, potentially, transmission) increasing unchecked. References

Boulangeat I, Gravel D, Thuiller W. Accounting for dispersal and biotic interactions to disentangle the drivers of species distributions and their abundances: The role of dispersal and biotic interactions in explaining species distributions and abundances. Ecol Lett. 2012;15: 584-593. Manley W, Tran T, Prusinski M, Brisson D. (2023) Modeling tick populations: An ecological test case for gradient boosted trees. bioRxiv, 2023.03.13.532443, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443 | Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted Trees | William Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">General linear models have been the foundational statistical framework used to discover the ecological processes that explain the distribution and abundance of natural populations. Analyses of the rapidly expanding ... | Parasitology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Timothée Poisot | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2023-03-23 23:41:17 | View | |

21 Oct 2020

Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate changeJames Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.26.117200Uncertain predictions of species responses to perturbations lead to underestimate changes at ecosystem level in diverse systemsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by Carlos Melian and 1 anonymous reviewerDifferent sources of uncertainty are known to affect our ability to predict ecological dynamics (Petchey et al. 2015). However, the consequences of uncertainty on prediction biases have been less investigated, especially when predictions are scaled up to higher levels of organisation as is commonly done in ecology for instance. The study of Orr et al. (2020) addresses this issue. It shows that, in complex systems, the uncertainty of unbiased predictions at a lower level of organisation (e.g. species level) leads to a bias towards underestimation of change at higher level of organisation (e.g. ecosystem level). This bias is strengthened by larger uncertainty and by higher dimensionality of the system. References Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, Kinzig AP, Daily GC, Loreau M, Grace JB, Larigauderie A, Srivastava DS, Naeem S (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148 | Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate change | James Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi | <p>Uncertainty is an irreducible part of predictive science, causing us to over- or underestimate the magnitude of change that a system of interest will face. In a reductionist approach, we may use predictions at the level of individual system com... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Theoretical ecology | Elisa Thebault | Anonymous | 2020-06-02 15:41:12 | View |

24 Mar 2023

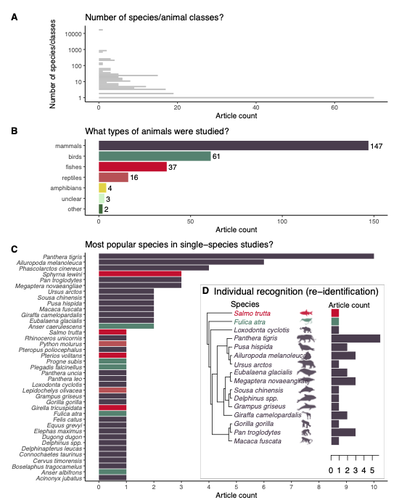

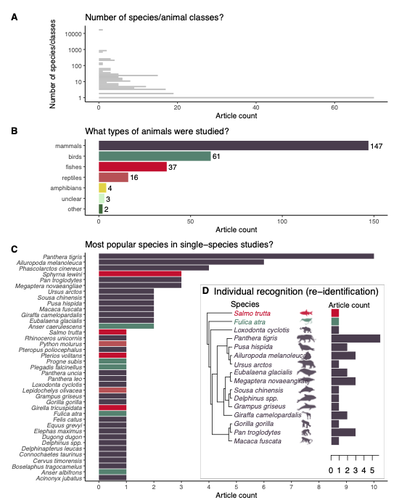

Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imageryShinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59DReview of machine learning uses for the analysis of images on wildlifeRecommended by Olivier Gimenez based on reviews by Falk Huettmann and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the field of ecology, there is a growing interest in machine (including deep) learning for processing and automatizing repetitive analyses on large amounts of images collected from camera traps, drones and smartphones, among others. These analyses include species or individual recognition and classification, counting or tracking individuals, detecting and classifying behavior. By saving countless times of manual work and tapping into massive amounts of data that keep accumulating with technological advances, machine learning is becoming an essential tool for ecologists. We refer to recent papers for more details on machine learning for ecology and evolution (Besson et al. 2022, Borowiec et al. 2022, Christin et al. 2019, Goodwin et al. 2022, Lamba et al. 2019, Nazir & Kaleem 2021, Perry et al. 2022, Picher & Hartig 2023, Tuia et al. 2022, Wäldchen & Mäder 2018). In their paper, Nakagawa et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of the literature on machine learning for wildlife imagery. Interestingly, the authors used a method unfamiliar to ecologists but well-established in medicine called rapid review, which has the advantage of being quickly completed compared to a fully comprehensive systematic review while being representative (Lagisz et al., 2022). Through a rigorous examination of more than 200 articles, the authors identified trends and gaps, and provided suggestions for future work. Listing all their findings would be counterproductive (you’d better read the paper), and I will focus on a few results that I have found striking, fully assuming a biased reading of the paper. First, Nakagawa et al. (2023) found that most articles used neural networks to analyze images, in general through collaboration with computer scientists. A challenge here is probably to think of teaching computer vision to the generations of ecologists to come (Cole et al. 2023). Second, the images were dominantly collected from camera traps, with an increase in the use of aerial images from drones/aircrafts that raise specific challenges. Third, the species concerned were mostly mammals and birds, suggesting that future applications should aim to mitigate this taxonomic bias, by including, e.g., invertebrate species. Fourth, most papers were written by authors affiliated with three countries (Australia, China, and the USA) while India and African countries provided lots of images, likely an example of scientific colonialism which should be tackled by e.g., capacity building and the involvement of local collaborators. Last, few studies shared their code and data, which obviously impedes reproducibility. Hopefully, with the journals’ policy of mandatory sharing of codes and data, this trend will be reversed. REFERENCES Besson M, Alison J, Bjerge K, Gorochowski TE, Høye TT, Jucker T, Mann HMR, Clements CF (2022) Towards the fully automated monitoring of ecological communities. Ecology Letters, 25, 2753–2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14123 Borowiec ML, Dikow RB, Frandsen PB, McKeeken A, Valentini G, White AE (2022) Deep learning as a tool for ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1640–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13901 Christin S, Hervet É, Lecomte N (2019) Applications for deep learning in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13256 Cole E, Stathatos S, Lütjens B, Sharma T, Kay J, Parham J, Kellenberger B, Beery S (2023) Teaching Computer Vision for Ecology. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.02211 Goodwin M, Halvorsen KT, Jiao L, Knausgård KM, Martin AH, Moyano M, Oomen RA, Rasmussen JH, Sørdalen TK, Thorbjørnsen SH (2022) Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: overview, applications, and outlook†. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255 Lagisz M, Vasilakopoulou K, Bridge C, Santamouris M, Nakagawa S (2022) Rapid systematic reviews for synthesizing research on built environment. Environmental Development, 43, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100730 Lamba A, Cassey P, Segaran RR, Koh LP (2019) Deep learning for environmental conservation. Current Biology, 29, R977–R982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.016 Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Francis R, Tam J, Li X, Elphinstone A, Jordan N, O’Brien J, Pitcher B, Sluys MV, Sowmya A, Kingsford R (2023) Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59D Nazir S, Kaleem M (2021) Advances in image acquisition and processing technologies transforming animal ecological studies. Ecological Informatics, 61, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101212 Perry GLW, Seidl R, Bellvé AM, Rammer W (2022) An Outlook for Deep Learning in Ecosystem Science. Ecosystems, 25, 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y Pichler M, Hartig F Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14061 Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, Risse B, Mathis A, Mathis MW, van Langevelde F, Burghardt T, Kays R, Klinck H, Wikelski M, Couzin ID, van Horn G, Crofoot MC, Stewart CV, Berger-Wolf T (2022) Perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. Nature Communications, 13, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27980-y Wäldchen J, Mäder P (2018) Machine learning for image-based species identification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13075 | Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery | Shinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford | <p>1. Machine (especially deep) learning algorithms are changing the way wildlife imagery is processed. They dramatically speed up the time to detect, count, classify animals and their behaviours. Yet, we currently have a very few systematic liter... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology | Olivier Gimenez | Anonymous | 2022-10-31 22:05:46 | View |

16 Nov 2020

Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functionsAllan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.10.144337Hidden diversity: how genetic richness affects species diversity and ecosystem processes in freshwater pondsRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Andrew Barnes and Jes HinesBiodiversity loss can have important consequences for ecosystem functions, as exemplified by a large body of literature spanning at least three decades [1–3]. While connections between species diversity and ecosystem functions are now well-defined and understood, the importance of diversity within species is more elusive. Despite a surge in theoretical work on how intraspecific diversity can affect coexistence in simple community types [4,5], not much is known about how intraspecific diversity drives ecosystem processes in more complex community types. One particular challenge is that intraspecific diversity can be expressed as observable variation of functional traits, or instead subsist as genetic variation of which the consequences for ecosystem processes are harder to grasp. References [1] Tilman D, Downing JA (1994) Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature, 367, 363–365. https://doi.org/10.1038/367363a0 | Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functions | Allan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. | <p>Loss in intraspecific diversity can alter ecosystem functions, but the underlying mechanisms are still elusive, and intraspecific biodiversity-ecosystem function relationships (iBEF) have been restrained to primary producers. Here, we manipulat... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Freshwater ecology | Frederik De Laender | Andrew Barnes | 2020-06-15 09:04:53 | View |

01 Jun 2018

Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecologyTimothée Poisot, Richard Labrie, Erin Larson, Anastasia Rahlin 10.1101/150128Some thoughts on computational ecology from people who I’m sure use different passwords for each of their accountsRecommended by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko based on reviews by Matthieu Barbier and 1 anonymous reviewerAre you an ecologist who uses a computer or know someone that does? Even if your research doesn’t rely heavily on advanced computational techniques, it likely hasn’t escaped your attention that computers are increasingly being used to analyse field data and make predictions about the consequences of environmental change. So before artificial intelligence and robots take over from scientists, now is great time to read about how experts think computers could make your life easier and lead to innovations in ecological research. In “Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology”, Poisot and colleagues [1] provide a brief history of computational ecology and offer their thoughts on how computational thinking can help to bridge different types of ecological knowledge. In this wide-ranging article, the authors share practical strategies for realising three main goals: (i) tighter integration of data and models to make predictions that motivate action by practitioners and policy-makers; (ii) closer interaction between data-collectors and data-users; and (iii) enthusiasm and aptitude for computational techniques in future generations of ecologists. The key, Poisot and colleagues argue, is for ecologists to “engage in meaningful dialogue across disciplines, and recognize the currencies of their collaborations.” Yes, this is easier said than done. However, the journey is much easier with a guide and when everyone involved serves to benefit not only from the eventual outcome, but also the process. References [1] Poisot, T., Labrie, R., Larson, E., & Rahlin, A. (2018). Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology. BioRxiv, 150128, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/150128 | Data-based, synthesis-driven: setting the agenda for computational ecology | Timothée Poisot, Richard Labrie, Erin Larson, Anastasia Rahlin | Computational ecology, defined as the application of computational thinking to ecological problems, has the potential to transform the way ecologists think about the integration of data and models. As the practice is gaining prominence as a way to... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Phillip P.A. Staniczenko | 2018-02-05 20:51:41 | View | |

02 Oct 2018

How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion.Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard 10.1101/273557Optimal foraging in a changing world: old questions, new perspectivesRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer

Marginal value theorem (MVT) is an archetypal model discussed in every behavioural ecology textbook. Its popularity is largely explained but the fact that it is possible to solve it graphically (at least in its simplest form) with the minimal amount of equations, which is a sensible strategy for an introductory course in behavioural ecology [1]. Apart from this heuristic value, one may be tempted to disregard it as a naive toy model. After a burst of interest in the 70's and the 80's, the once vivid literature about optimal foraging theory (OFT) has lost its momentum [2]. Yet, OFT and MVT have remained an active field of research in the parasitoidologists community, mostly because the sampling strategy of a parasitoid in patches of hosts and its resulting fitness gain are straightforward to evaluate, which eases both experimental and theoretical investigations [3]. References [1] Fawcett, T. W. & Higginson, A. D. 2012 Heavy use of equations impedes communication among biologists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 11735–11739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205259109 | How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion. | Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard | The Marginal Value Theorem (MVT) provides a framework to predict how habitat modifications related to the distribution of resources over patches should impact the realized fitness of individuals and their optimal rate of movement (or patch residen... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2018-03-05 10:42:11 | View | |

29 Dec 2018

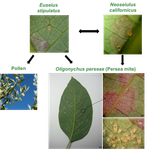

The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food webInmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat https://doi.org/10.1101/324178From deserts to avocado orchards - understanding realized trophic interactions in communitiesRecommended by Francis John Burdon based on reviews by Owen Petchey and 2 anonymous reviewersThe late eminent ecologist Gary Polis once stated that “most catalogued food-webs are oversimplified caricatures of actual communities” and are “grossly incomplete representations of communities in terms of both diversity and trophic connections.” Not content with that damning indictment, he went further by railing that “theorists are trying to explain phenomena that do not exist” [1]. The latter critique might have been push back for Robert May´s ground-breaking but ultimately flawed research on the relationship between food-web complexity and stability [2]. Polis was a brilliant ecologist, and his thinking was clearly influenced by his experiences researching desert food webs. Those food webs possess an uncommon combination of properties, such as frequent omnivory, cannibalism, and looping; high linkage density (L/S); and a nearly complete absence of apex consumers, since few species completely lack predators or parasites [3]. During my PhD studies, I was lucky enough to visit Joshua Tree National Park on the way to a conference in New England, and I could immediately see the problems posed by desert ecosystems. At the time, I was ruminating on the “harsh-benign” hypothesis [4], which predicts that the relative importance of abiotic and biotic forces should vary with changes in local environmental conditions (from harsh to benign). Specifically, in more “harsh” environments, abiotic factors should determine community composition whilst weakening the influence of biotic interactions. However, in the harsh desert environment I saw first-hand evidence that species interactions were not diminished; if anything, they were strengthened. Teddy-bear chollas possessed murderously sharp defenses to protect precious water, creosote bushes engaged in belowground “chemical warfare” (allelopathy) to deter potential competitors, and rampant cannibalism amongst scorpions drove temporal and spatial ontogenetic niche partitioning. Life in the desert was hard, but you couldn´t expect your competition to go easy on you. References [1] Polis, G. A. (1991). Complex trophic interactions in deserts: an empirical critique of food-web theory. The American Naturalist, 138(1), 123-155. doi: 10.1086/285208 | The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web | Inmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat | <p>The mathematical theory describing small assemblages of interacting species (community modules or motifs) has proved to be essential in understanding the emergent properties of ecological communities. These models use differential equations to ... |  | Community ecology, Experimental ecology | Francis John Burdon | 2018-05-16 19:34:10 | View | |

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View | |

10 Jun 2018

A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis”Charpentier MJE, Kappeler PM https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.08151v3Does elevated parasite richness in the environment affect daily path length of animals or is it the converse? An answer bringing some new elements of discussionRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In 2015, Brockmeyer et al. [1] suggested that mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) may accept additional ranging costs to avoid heavily parasitized areas. Following this paper, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] questioned this interpretation and presented other hypotheses. To summarize, whilst Brockmeyer et al. [1] proposed that elevated daily path length may be a consequence of elevated parasite richness, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] viewed it as a cause. In this current paper, Charpentier and Kappeler [3] respond to some of the criticisms by Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques and discuss the putative parsimony of the two competing scenarios. The manuscript is interesting and focuses on an important question concerning the discussion about the social organization and home range use in wild mandrills. This answer helps to move this debate forward and should stimulate more empirical studies of the role of environmentally-transmitted parasites in shaping ranging and movement patterns of wild vertebrates. Given the elements this paper brings to the topics, it should have been published in American Journal of Primatology, the journal that published the two previous articles. References [1] Brockmeyer, T., Kappeler, P. M., Willaume, E., Benoit, L., Mboumba, S., & Charpentier, M. J. E. (2015). Social organization and space use of a wild mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) group. American Journal of Primatology, 77(10), 1036–1048. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22439 | A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis” | Charpentier MJE, Kappeler PM | In a recent article, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2016] discussed the putative assumptions related to an interpretation we provided regarding an observed positive relationship between weekly averaged parasite richness of a group of mandrill... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Foraging, Host-parasite interactions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Zoology | Cédric Sueur | 2018-05-22 10:59:33 | View | |

16 Oct 2018

Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus)Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4How empirical sciences may improve livestock welfare and help their managementRecommended by Marie Charpentier based on reviews by Alecia CARTER and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding how livestock management is a source of social stress and disturbances for cattle is an important question with potential applications for animal welfare programs and sustainable development. In their article, Sosa and colleagues [1] first propose to evaluate the effects of individual characteristics on dyadic social relationships and on the social dynamics of four groups of cattle. Using network analyses, the authors provide an interesting and complete picture of dyadic interactions among groupmates. Although shown elsewhere, the authors demonstrate that individuals that are close in age and close in rank form stronger dyadic associations than other pairs. Second, the authors take advantage of some transfers of animals between groups -for management purposes- to assess how these transfers affect the social dynamics of groupmates. Their central finding is that the identity of transferred animals is a key-point. In particular, removing offspring strongly destabilizes the social relationships of mothers while adding a bull into a group also profoundly impacts female-female social relationships, as social networks before and after transfer of these key-animals are completely different. In addition, individuals, especially the young ones, that are transferred without familiar conspecifics take more time to socialize with their new group members than individuals transferred with familiar groupmates, generating a potential source of stress. Interestingly, the authors end up their article with some thoughts on the implications of their findings for animal welfare and ethics. This study provides additional evidence that empirical science has a major role to play in providing recommendations regarding societal questions such as livestock management and animal wellbeing. References [1] Sosa, S., Pelé, M., Debergue, E., Kuntz, C., Keller, B., Robic, F., Siegwalt-Baudin, F., Richer, C., Ramos, A., & Sueur C. (2018). Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus). arXiv:1805.11553v4 [q-bio.PE] peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4 | Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus) | Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur | The sociality of cattle facilitates the maintenance of herd cohesion and synchronisation, making these species the ideal choice for domestication as livestock for humans. However, livestock populations are not self-regulated, and farmers transfer ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure | Marie Charpentier | 2018-05-30 14:05:39 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle