Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▼ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Jan 2024

Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation : should we go fractal?Fabien Laroche https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.29.501974Spatial patterns and autocorrelation challenges in ecological conservationRecommended by Eric Goberville based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and Charles J Marsh based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and Charles J Marsh

“Pattern, like beauty, is to some extent in the eye of the beholder” (Grant 1977 in Wiens, 1989) Ecologists are immersed in unraveling the complex spatial patterns that govern species diversity, driven by both practical and theoretical imperatives (Rahbek, 2005; Wang et al., 2019). This dual focus necessitates a practical imperative for strategic biodiversity conservation, requiring a nuanced understanding of locations with peak species richness and dynamic shifts in species assemblages (Chase et al., 2020). Simultaneously, there is a theoretical interest in using diversity patterns as empirical testing grounds for theories explaining factors influencing diversity disparities and the associated increase in species turnover correlated with inter-site distance (Condit et al., 2002).

McGill (2010), in his paper "Matters of Scale", highlights the scale-dependent nature of ecology, aligning with the recognition that spatial autocorrelation is inherent in biogeographical data and often correlated with sample size (Rahbek, 2005). Spatial autocorrelation, often underestimated in ecological studies (Dormann, 2007), occurs when proximate locations exhibit similarities in ecological attributes (Tobler, 1970; Getis, 2010), introducing a latent bias that compromises the robustness of ecological findings (Dormann, 2007; Dormann et al., 2007). This phenomenon serves as both an asset, providing valuable information for inferring processes from patterns (Palma et al. 1999), and a challenge, imposing limitations on hypothesis testing and prediction (Dormann et al., 2007 and references therein). Various factors contribute to spatial autocorrelation, with three primary contributors (Dormann et al., 2007; Legendre, 1993; Legendre and Fortin, 1989; Legendre and Legendre, 2012): (i) distance-related effects in biological processes, (ii) misrepresentation of non-linear relationships between the environment and species as linear and (iii) the oversight of a crucial spatially structured environmental determinant in the statistical model, leading to spatial structuring in the response (Dormann et al., 2007).

Recognising the pivotal role of spatial heterogeneity in ecological theories (Wang et al., 2019), it becomes imperative to discern and address the limitations introduced by spatial autocorrelation (Legendre, 1993). McGill (2011) emphasises that the ultimate goal of biodiversity pattern studies should be to develop a quantitative predictive theory useful for conservation. The spatial dimension's importance in study planning, determining the system's scale, appropriate quadrat size, and spacing between sampling stations, is paramount (Fortin, 1999a,b). Responses to these considerations are intricately linked with study objectives and insights from pre-sampling campaigns, underscoring the need for a nuanced and rigorous approach (Delmelle, 2021).

Understanding statistical techniques and nested sampling designs is crucial to answering fundamental ecological questions (Dormann et al., 2007; McDonald, 2012). In addressing spatial autocorrelation challenges, ecologists must recognize the limitations of many standard statistical methods in ecological studies (Dale and Fortin, 2002; Legendre and Fortin, 1989; Steel et al., 2013). In the initial phases of description or hypothesis generation, ecologists should proactively acknowledge the spatial structure in their data and conduct tests for spatial autocorrelation (for a comprehensive description, see Legendre and Fortin, 1989): various tools, including correlograms, spectral analysis, the Mantel test, and clustering methods, facilitate the assessment and description of spatial structures. The partial Mantel test enables the study of causal models with space as an explanatory variable. Techniques for mapping ecological variables, such as interpolation, trend surface analysis, and constrained clustering, yield maps providing valuable insights into the spatial dynamics of ecological systems.

This refined consideration of spatial autocorrelation emerges as an imperative in ecological research, fostering a deeper and more precise understanding of the intricate interplay between species diversity, spatial patterns, and the inherent limitations imposed by spatial autocorrelation (Legendre et al., 2002). This not only contributes significantly to the scientific discourse in ecology but also aligns with McGill's vision of developing predictive theories for effective conservation (Bacaro et al., 2016; McGill, 2011).

In this study by Fabien Laroche (2023), titled “Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation: should we go fractal?” the primary focus was on addressing the challenges associated with estimating the autocorrelation range of species distribution across spatial scales. The study aimed to explore alternative sampling designs, with a particular focus on the application of fractal designs—self-similar designs with well-identified scales. The overarching goal was to evaluate whether fractal designs could offer a more efficient compromise compared to traditional hybrid designs, which involve mixing random sampling points with a systematic grid.

Virtual ecology provides a way to test whether sampling designs can accurately detect or quantify effects of interest before implementing them in the field. Beyond the question of assessing the power of empirical designs, a virtual ecology analysis contributes to clearly formulating the set of questions associated with a design. However, only a few virtual studies have focused on efficient designs to accurately estimate the autocorrelation range of biodiversity variables. In this study, the statistical framework of optimal design of experiments was employed—a methodology often used in building and comparing designs of temporal or spatiotemporal biodiversity surveys but rarely applied to the specific problem of quantifying spatial autocorrelation.

Key findings from the study shed light on optimal sampling strategies, with a notable dependence on the feasible grid mesh size over the study area in relation to expected autocorrelation range values. The results demonstrated that the efficiency of designs varied based on the specific effect under study. Fractal designs, however, exhibited superior performance, particularly when assessing the effect of a monotonic environmental gradient across space.

In conclusion, the study provides valuable insights into the potential benefits of incorporating fractal designs in biodiversity studies, offering a nuanced and efficient approach to estimate spatial autocorrelation. These findings contribute significantly to the ongoing scientific discourse in ecology, providing practical considerations for improving sampling designs in biodiversity assessments.

References

Bacaro, G., Altobelli, A., Cameletti, M., Ciccarelli, D., Martellos, S., Palmer, M.W., Ricotta, C., Rocchini, D., Scheiner, S.M., Tordoni, E., Chiarucci, A., 2016. Incorporating spatial autocorrelation in rarefaction methods: Implications for ecologists and conservation biologists. Ecological Indicators 69, 233-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.04.026

Chase, J.M., Jeliazkov, A., Ladouceur, E., Viana, D.S., 2020. Biodiversity conservation through the lens of metacommunity ecology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1469, 86-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14378

Condit, R., Pitman, N., Leigh, E.G., Chave, J., Terborgh, J., Foster, R.B., Núñez, P., Aguilar, S., Valencia, R., Villa, G., Muller-Landau, H.C., Losos, E., Hubbell, S.P., 2002. Beta-Diversity in Tropical Forest Trees. Science 295, 666-669. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066854

Dale, M.R.T., Fortin, M.-J., 2002. Spatial autocorrelation and statistical tests in ecology. Écoscience 9, 162-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2002.11682702

Delmelle, E.M., 2021. Spatial Sampling, in: Fischer, M.M., Nijkamp, P. (Eds.), Handbook of Regional Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1829-1844.

Dormann, C.F., 2007. Effects of incorporating spatial autocorrelation into the analysis of species distribution data. Global Ecology & Biogeography 16, 129-128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00279.x

Dormann, C.F., McPherson, J.M., Araújo, M.B., Bivand, R., Bolliger, J., Carl, G., Davies, R.G., Hirzel, A., Jetz, W., Kissling, W.D., Kühn, I., Ohlemüler, R., Peres-Neto, P.R., Reineking, B., Schröder, B., Schurr, F.M., Wilson, R., 2007. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review. Ecography 33, 609-628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05171.x

Fortin, M.-J., 1999a. Effects of quadrat size and data measurement on the detection of boundaries. Journal of Vegetation Science 10, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3237159

Fortin, M.-J., 1999b. Effects of sampling unit resolution on the estimation of spatial autocorrelation. Écoscience 6, 636-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.1999.11682547

Getis, A., 2010. Spatial Autocorrelation, in: Fischer, M.M., Getis, A. (Eds.), Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 255-278.

Laroche, F., 2023. Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation: should we go fractal? bioRxiv, 2022.07.29.501974, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.29.501974

Legendre, P., 1993. Spatial Autocorrelation: Trouble or New Paradigm? Ecology 74, 1659-1673. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939924

Legendre, P., Dale, M.R.T., Fortin, M.-J., Gurevitch, J., Hohn, M., Myers, D., 2002. The consequences of spatial structure for the design and analysis of ecological field surveys. Ecography 25, 601-615. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0587.2002.250508.x

Legendre, P., Fortin, M.J., 1989. Spatial pattern and ecological analysis. Vegetatio 80, 107-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00048036

Legendre, P., Legendre, L., 2012. Numerical Ecology, Third Edition ed. Elsevier, The Netherlands.

McDonald, T., 2012. Spatial sampling designs for long-term ecological monitoring, in: Cooper, A.B., Gitzen, R.A., Licht, D.S., Millspaugh, J.J. (Eds.), Design and Analysis of Long-term Ecological Monitoring Studies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 101-125.

McGill, B.J., 2010. Matters of Scale. Science 328, 575-576. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188528

McGill, B.J., 2011. Linking biodiversity patterns by autocorrelated random sampling. American Journal of Botany 98, 481-502. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1000509

Rahbek, C., 2005. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns. Ecology Letters 8, 224-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00701.x

Steel, E.A., Kennedy, M.C., Cunningham, P.G., Stanovick, J.S., 2013. Applied statistics in ecology: common pitfalls and simple solutions. Ecosphere 4, art115. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00160.1

Tobler, W.R., 1970. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Economic Geography 46, 234-240. https://doi.org/10.2307/143141

Wang, S., Lamy, T., Hallett, L.M., Loreau, M., 2019. Stability and synchrony across ecological hierarchies in heterogeneous metacommunities: linking theory to data. Ecography 42, 1200-1211. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04290

Wiens, J.A., 1989. The ecology of bird communities. Cambridge University Press.

| Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation : should we go fractal? | Fabien Laroche | <p>Quantifying the autocorrelation range of species distribution in space is necessary for applied ecological questions, like implementing protected area networks or monitoring programs. However, the power of spatial sampling designs to estimate t... |  | Biodiversity, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Statistical ecology | Eric Goberville | 2023-04-21 10:54:29 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

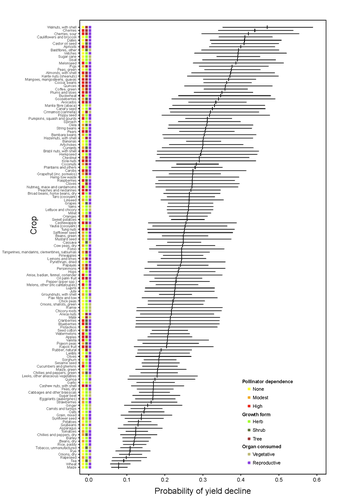

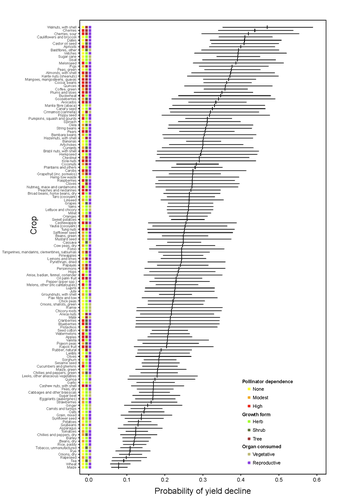

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

03 Oct 2023

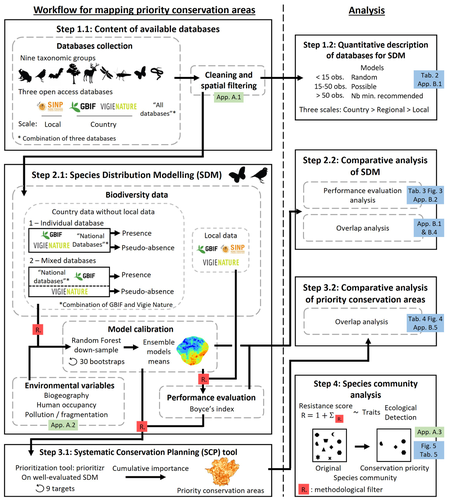

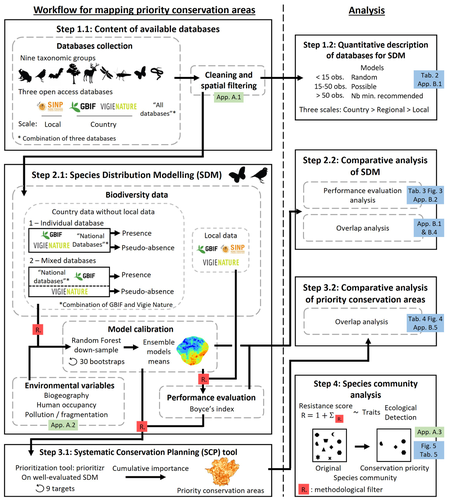

Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sourcesThibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999Biodiversity databases are ever more numerous, but can they be used reliably for Species Distribution Modelling?Recommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Proposing efficient guidelines for biodiversity conservation often requires the use of forecasting tools. Species Distribution Models (SDM) are more and more used to predict how the distribution of a species will react to environmental change, including any large-scale management actions that could be implemented. Their use is also boosted by the increase of publicly available biodiversity databases[1]. The now famous aphorism by George Box "All models are wrong but some are useful"[2] very well summarizes that the outcome of a model must be adjusted to, and will depend on, the data that are used to parameterize it. The question of the reliability of using biodiversity databases to parameterize biodiversity models such as SDM –but the question would also apply to other kinds of biodiversity models, e.g. Population Viability Analysis models[3]– is key to determine the confidence that can be placed in model predictions. This point is often overlooked by some categories of biodiversity conservation stakeholders, in particular the fact that some data were collected using controlled protocols while others are opportunistic. In this study[4], the authors use a collection of databases covering a range of species as well as of geographic scales in France and using different data collection and validation approaches as a case study to evaluate the impact of data quality when performing Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Among their conclusions, the fact that a large-scale database (what they call the “country” level) is necessary to reliably parameterize SDM. Besides this and other conclusions of their study, which are likely to be in part specific to their case study –unfortunately for its conservation, biodiversity is complex and varies a lot–, the merit of this work lies in the approach used to test the impact of data on model predictions. References 1. Feng, X. et al. A review of the heterogeneous landscape of biodiversity databases: Opportunities and challenges for a synthesized biodiversity knowledge base. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31, 1242–1260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13497 2. Box, G. E. P. Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building. in Robustness in Statistics (eds. Launer, R. L. & Wilkinson, G. N.) 201–236 (Academic Press, 1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-438150-6.50018-2. 3. Beissinger, S. R. & McCullough, D. R. Population Viability Analysis. (The University of Chicago Press, 2002). 4. Ferraille, T., Kerbiriou, C., Bigard, C., Claireau, F. & Thompson, J. D. (2023) Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999 | Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources | Thibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson | <p>Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of land-use planning is a fundamental tool to minimize environmental impacts of artificialization. In this context, Systematic Conservation Planning (SCP) tools based on Species Distribution Models (SDM)... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-05-11 09:41:05 | View | |

11 Aug 2023

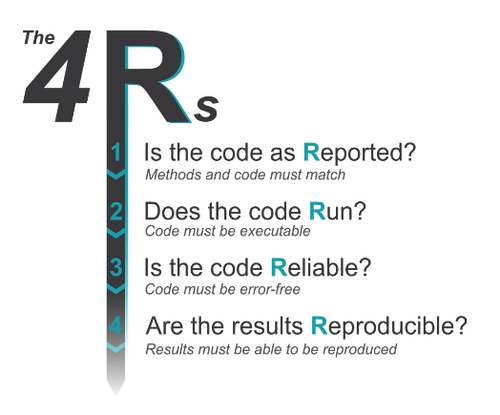

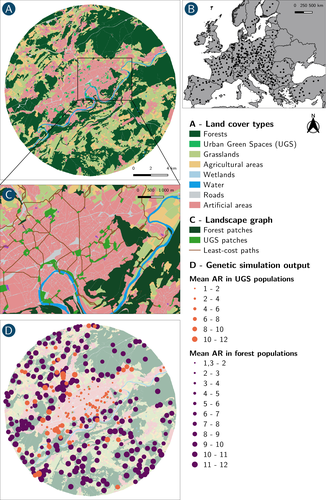

Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary BiologyEdward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64A handy “How to” review code for ecologists and evolutionary biologistsRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewerIvimey Cook et al. (2023) provide a concise and useful “How to” review code for researchers in the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology, where the systematic review of code is not yet standard practice during the peer review of articles. Consequently, this article is full of tips for authors on how to make their code easier to review. This handy article applies not only to ecology and evolutionary biology, but to many fields that are learning how to make code more reproducible and shareable. Taking this step toward transparency is key to improving research rigor (Brito et al. 2020) and is a necessary step in helping make research trustable by the public (Rosman et al. 2022). References Brito, J. J., Li, J., Moore, J. H., Greene, C. S., Nogoy, N. A., Garmire, L. X., & Mangul, S. (2020). Recommendations to enhance rigor and reproducibility in biomedical research. GigaScience, 9(6), giaa056. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa056 Ivimey-Cook, E. R., Pick, J. L., Bairos-Novak, K., Culina, A., Gould, E., Grainger, M., Marshall, B., Moreau, D., Paquet, M., Royauté, R., Sanchez-Tojar, A., Silva, I., Windecker, S. (2023). Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. EcoEvoRxiv, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64 Rosman, T., Bosnjak, M., Silber, H., Koßmann, J., & Heycke, T. (2022). Open science and public trust in science: Results from two studies. Public Understanding of Science, 31(8), 1046-1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221100686 | Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Edward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker | <p>Code review increases reliability and improves reproducibility of research. As such, code review is an inevitable step in software development and is common in fields such as computer science. However, despite its importance, code review is not... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology | Corina Logan | 2023-05-19 15:54:01 | View | |

11 Mar 2024

Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammalAmin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920Stress and stress hormones’ transmission from mothers to offspringRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Individuals can respond to environmental changes that they undergo directly (within-generation plasticity) but also through transgenerational plasticity, providing lasting effects that are transmitted to the next generations (Donelson et al. 2012; Munday et al. 2013; Kuijper & Hoyle 2015; Auge et al. 2017, Tariel et al. 2020). These parental effects can affect offspring via various mechanisms, notably via maternal transmission of hormones to the eggs or growing embryos (Mousseau & Fox 1998). While the effects of environmental quality may simply carry-over to the next generation (e.g., females in stressful environments give birth to offspring in poorer condition), parental effects may also be a mechanism that adjusts offspring phenotype in response to environmental variation and predictability, and thereby match offspring's phenotype to future environmental conditions (Gluckman et al. 2005; Marshall & Uller 2007; Dey et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2019), for example by preparing their offspring to an expected stressful environment. When females experience stress during gestation or egg formation, elevations in glucocorticoids (GC) are expected to affect offspring phenotype in many ways, from the offspring's own GC levels, to their growth and survival (Sheriff et al. 2017). This is a well established idea, but how strong is the evidence for this? A meta-analysis on birds found no clear effect of corticosterone manipulation on offspring traits (38 studies on 9 bird species for corticosterone manipulation; Podmokła et al. 2018). Another meta-analysis including 14 vertebrate species found no clear effect of prenatal stress on offspring GC (Thayer et al. 2018). Finally, a meta-analysis on wild vertebrates (23 species) found no clear effect of GC-mediated maternal effects on offspring traits (MacLeod et al. 2021). As often when facing such inconclusive results, context dependence has been suggested as one potential reason for such inconsistencies, for exemple sex specific effects (Groothuis et al. 2019, 2020). However, sex specific measures on offspring are scarce (Podmokła et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature available is still limited to a few, mostly “model” species. With their study, Amin et al. (2024) show the way to improve our understanding on GC transmission from mother to offspring and its effects in several aspects. First they used innovative non-invasive methods (which could broaden the range of species available to study) by quantifying cortisol metabolites from faecal samples collected from pregnant females, as proxy for maternal GC level, and relating it to GC levels from hairs of their neonate offspring. Second they used a free ranging large mammal (taxa from which literature is missing): the fallow deer (Dama dama). Third, they provide sex specific measures of GC levels. And finally but importantly, they are exemplary in their transparency regarding 1) the exploratory nature of their study, 2) their statistical thinking and procedure, and 3) the study limitations (e.g., low sample size and high within individual variation of measurements). I hope this study will motivate more research (on the fallow deer, and on other species) to broaden and strengthen our understanding of sex specific effects of maternal stress and CG levels on offspring phenotype and fitness. References Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., & Ciuti, S. (2024). Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and foetal glucocorticoids in a free-ranging large mammal. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920 Auge, G.A., Leverett, L.D., Edwards, B.R. & Donohue, K. (2017). Adjusting phenotypes via within-and across-generational plasticity. New Phytologist, 216, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14495 Dey, S., Proulx, S.R. & Teotonio, H. (2016). Adaptation to temporally fluctuating environments by the evolution of maternal effects. PLoS biology, 14, e1002388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002388 Donelson, J.M., Munday, P.L., McCormick, M.I. & Pitcher, C.R. (2012). Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1323 Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A. & Spencer, H.G. (2005). Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001 Groothuis, Ton GG, Bin-Yan Hsu, Neeraj Kumar, and Barbara Tschirren. "Revisiting mechanisms and functions of prenatal hormone-mediated maternal effects using avian species as a model." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374, no. 1770 (2019): 20180115. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0115 Groothuis, Ton GG, Neeraj Kumar, and Bin-Yan Hsu. "Explaining discrepancies in the study of maternal effects: the role of context and embryo." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36 (2020): 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.10.006 Kuijper, B. & Hoyle, R.B. (2015). When to rely on maternal effects and when on phenotypic plasticity? Evolution, 69, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12635 MacLeod, Kirsty J., Geoffrey M. While, and Tobias Uller. "Viviparous mothers impose stronger glucocorticoid‐mediated maternal stress effects on their offspring than oviparous mothers." Ecology and Evolution 11, no. 23 (2021): 17238-17259. Marshall, D.J. & Uller, T. (2007). When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos, 116, 1957–1963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x Mousseau, T.A. & Fox, C.W. (1998). Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press. Munday, P.L., Warner, R.R., Monro, K., Pandolfi, J.M. & Marshall, D.J. (2013). Predicting evolutionary responses to climate change in the sea. Ecology Letters, 16, 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12185 Podmokła, Edyta, Szymon M. Drobniak, and Joanna Rutkowska. "Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method–a meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 93, no. 3 (2018): 1499-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12406 Sheriff, M. J., Bell, A., Boonstra, R., Dantzer, B., Lavergne, S. G., McGhee, K. E., MacLeod, K. J., Winandy, L., Zimmer, C., & Love, O. P. (2017). Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105 Tariel, Juliette, Sandrine Plénet, and Émilien Luquet. "Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (2020): 548660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.548660 Thayer, Zaneta M., Meredith A. Wilson, Andrew W. Kim, and Adrian V. Jaeggi. "Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: A phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species." Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 4942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23169-w Yin, J., Zhou, M., Lin, Z., Li, Q.Q. & Zhang, Y.-Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects benefit offspring across diverse environments: a meta-analysis in plants and animals. Ecology letters, 22, 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13373 | Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammal | Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Maternal phenotypes can have long-term effects on offspring phenotypes. These maternal effects may begin during gestation, when maternal glucocorticoid (GC) levels may affect foetal GC levels, thereby having an orga... | Evolutionary ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Physiology, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-06-05 09:06:56 | View | ||

19 Mar 2024

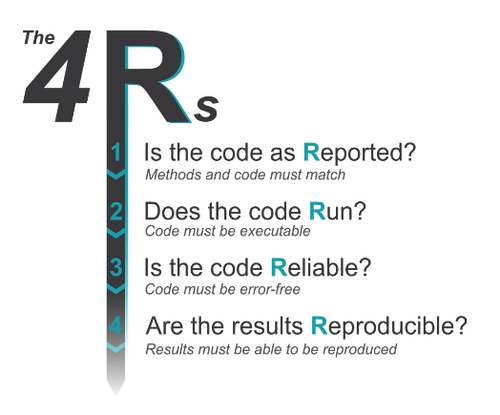

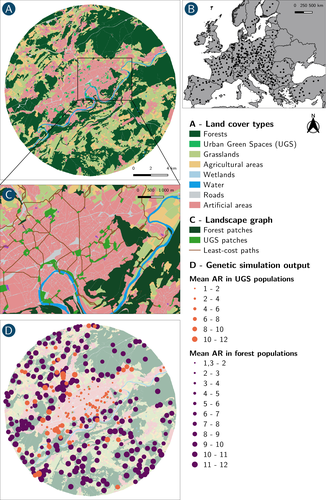

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View | |

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

12 Jan 2024

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonisAlexius Folk, Adele Mennerat https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695Marking invertebrates using RFID tagsRecommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer

Guiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically. The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it. References Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013 Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008. Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695 Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082 Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900 | Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse *Lepeophtheirus salmonis* | Alexius Folk, Adele Mennerat | <p style="text-align: justify;">Monitoring individuals within populations is a cornerstone in evolutionary ecology, yet individual tracking of invertebrates and particularly parasitic organisms remains rare. To address this gap, we describe here a... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Marine ecology, Parasitology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-09-04 15:25:08 | View | |

15 Feb 2024

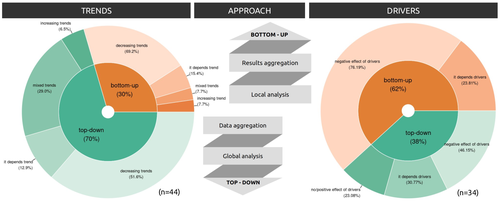

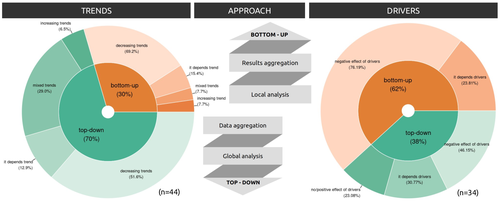

Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trendsMaelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3HUnraveling the Complexity of Global Biodiversity Dynamics: Insights and ImperativesRecommended by Paulo Borges based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer

Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across terrestrial and marine ecosystems, driven by various processes that degrade habitats and threaten species with extinction. Despite the urgency of this issue, empirical studies present a mixed picture, with some indicating declining trends while others show more complex patterns. In a recent effort to better understand global biodiversity dynamics, Boennec et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive literature review examining temporal trends in biodiversity. Their analysis reveals that reviews and meta-analyses, coupled with the use of global indicators, tend to report declining trends more frequently. Additionally, the study underscores a critical gap in research: the scarcity of investigations into the combined impact of multiple pressures on biodiversity at a global scale. This lack of understanding complicates efforts to identify the root causes of biodiversity changes and develop effective conservation strategies. This study serves as a crucial reminder of the pressing need for long-term biodiversity monitoring and large-scale conservation studies. By filling these gaps in knowledge, researchers can provide policymakers and conservation practitioners with the insights necessary to mitigate biodiversity loss and safeguard ecosystems for future generations. References Boennec, M., Dakos, V. & Devictor, V. (2023). Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trend. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3H

| Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trends | Maelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor | <p>Populations and ecological communities are changing worldwide, and empirical studies exhibit a mixture of either declining or mixed trends. Confusion in global biodiversity trends thus remains while assessing such changes is of major social, po... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Meta-analyses | Paulo Borges | 2023-09-20 11:10:25 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

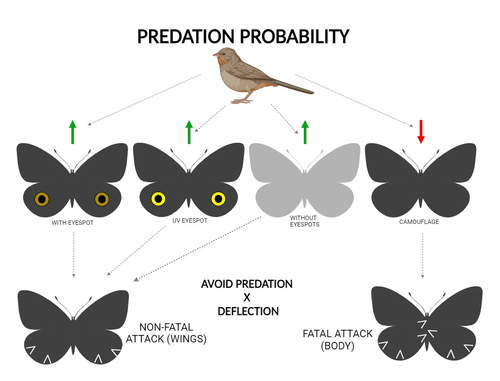

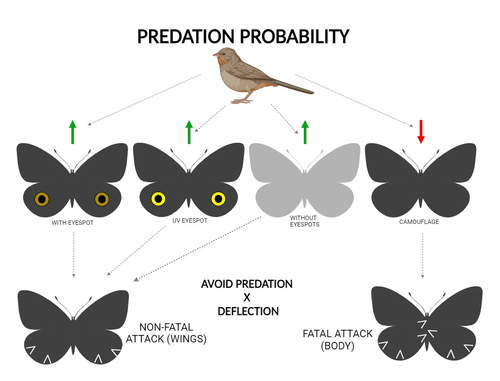

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle