Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

20 Feb 2024

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practicesIsis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persistRecommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich

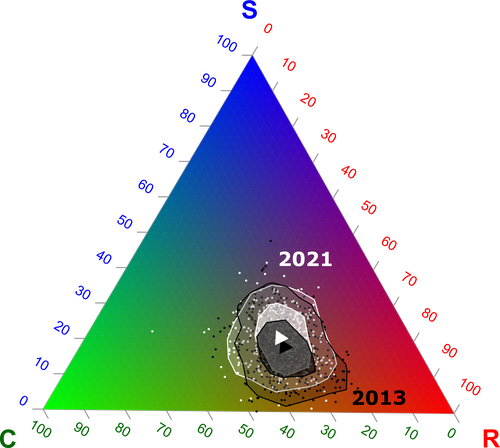

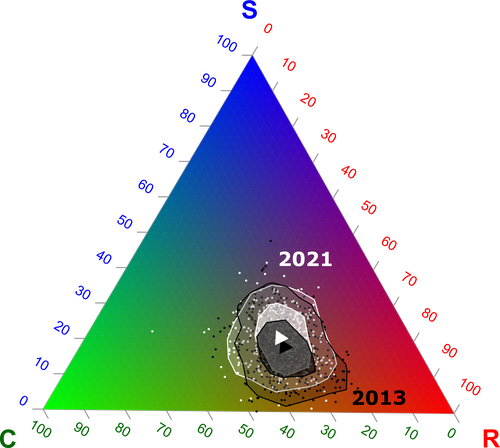

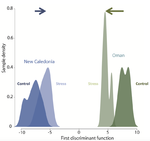

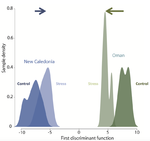

Agricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ. References Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013 Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2 Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005 Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244 Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14 Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain. Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003 Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956 Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715 | Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices | Isis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried | <p style="text-align: justify;">Over the past decades, agricultural intensification and climate change have led to vegetation shifts. However, functional trade-offs linking traits responding to climate and farming practices are rarely analyzed, es... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Climate change, Community ecology | Julia Astegiano | 2023-03-04 15:40:35 | View | |

04 Sep 2019

Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora coralsK. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza https://doi.org/10.1101/398602Transcriptomics of thermal stress response in coralsRecommended by Staffan Jacob based on reviews by Mar SobralClimate change presents a challenge to many life forms and the resulting loss of biodiversity will critically depend on the ability of organisms to timely respond to a changing environment. Shifts in ecological parameters have repeatedly been attributed to global warming, with the effectiveness of these responses varying among species [1, 2]. Organisms do not only have to face a global increase in mean temperatures, but a complex interplay with another crucial but largely understudied aspect of climate change: thermal fluctuations. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adaptation to thermal fluctuations is thus a timely and critical challenge. References [1] Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286 | Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora corals | K. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza | <p>Ecosystems worldwide are suffering from climate change. Coral reef ecosystems are globally threatened by increasing sea surface temperatures. However, gene expression plasticity provides the potential for organisms to respond rapidly and effect... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Symbiosis | Staffan Jacob | 2018-08-29 10:46:55 | View | |

13 May 2024

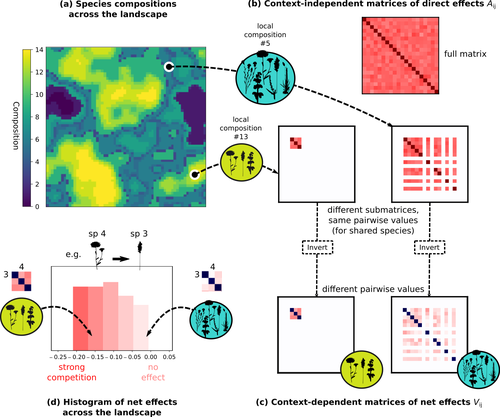

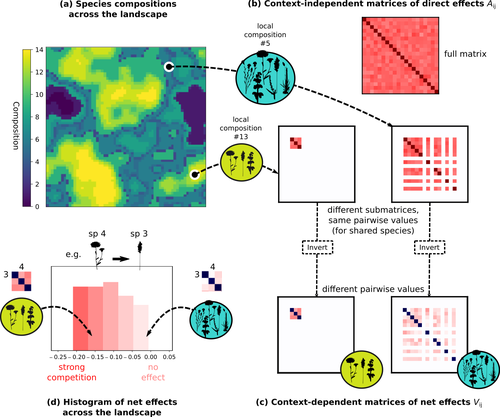

Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in MetacommunitiesMatthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.04.543606Beyond pairwise species interactions: coarser inference of their joined effects is more relevantRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler

Barbier et al. (2024) investigated the dynamics of species abundances depending on their ecological niche (abiotic component) and on (numerous) competitive interactions. In line with previous evidence and expectations (Barbier et al. 2018), the authors show that it is possible to robustly infer the mean and variance of interaction coefficients from species co-distributions, while it is not possible to infer the individual coefficient values. The authors devised a simulation framework representing multispecies dynamics in an heterogeneous environmental context (2D grid landscape). They used a Lotka-Volterra framework involving pairwise interaction coefficients and species-specific carrying capacities. These capacities depend on how well the species niche matches the local environmental conditions, through a Gaussian function of the distance of the species niche centers to the local environmental values. They considered two contrasted scenarios denoted as « Environmental tracking » and « Dispersal limited ». In the latter case, species are initially seeded over the environmental grid and cannot disperse to other cells, while in the former case they can disperse and possibly be more performant in other cells. The direct effects of species on one another are encoded in an interaction matrix A, and the authors further considered net interactions depending on the inverse of the matrix of direct interactions (Zelnik et al., 2024). The net effects are context-dependent, i.e., it involves the environment-dependent biotic capacities, even through the interaction terms can be defined between species as independent from local environment. The results presented here underline that the outcome of many individual competitive interactions can only be understood in terms of macroscopic properties. In essence, the results here echoe the mean field theories that investigate the dynamics of average ecological properties instead of the microscopic components (e.g., McKane et al. 2000). In a philosophical perspective, community ecology has long struggled with analyzing and inferring local determinants of species coexistence from species co-occurrence patterns, so that it was claimed that no universal laws can be derived in the discipline (Lawton 1999). Using different and complementary methods and perspectives, recent research has also shown that species assembly parameter values cannot be unambiguously inferred from species co-occurrences only, even in simple designs where an equilibrium can be reached (Poggiato et al. 2021). Although the roles of high-order competitive interactions and intransivity can lead to species coexistence, the simple view of a single loop of competitive interactions is easily challenged when further interactions and complexity is added (Gallien et al. 2024). But should we put so much emphasis on inferring individual interaction coefficients? In a quest to understand the emerging properties of elementary processes, ecological theory could go forward with a more macroscopic analysis and understanding of species coexistence in many communities. The authors referred several times to an interesting paper from Schaffer (1981), entitled « Ecological abstraction: the consequences of reduced dimensionality in ecological models ». It proposes that estimating individual species competition coefficients is not possible, but that competition can be assessed at the coarser level of organisation, i.e., between ecological guilds. This idea implies that the dimensionality of the competition equations should be greatly reduced to become tractable in practice. Taking together this claim with the results of the present Barbier et al. (2024) paper, it becomes clearer that the nature of competitive interactions can be addressed through « abstracted » quantities, as those of guilds or the moments of the individual competition coefficients (here the average and the standard deviation). Therefore the scope of Barbier et al. (2024) framework goes beyond statistical issues in parameter inference, but question the way we must think and represent the numerous competitive interactions in a simplified and robust way. References Barbier, Matthieu, Jean-François Arnoldi, Guy Bunin, et Michel Loreau. 2018. « Generic assembly patterns in complex ecological communities ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9): 2156‑61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710352115 | Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in Metacommunities | Matthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold | <p>AbstractOne of the more difficult challenges in community ecology is inferring species interactions on the basis of patterns in the spatial distribution of organisms. At its core, the problem is that distributional patterns reflect the ‘realize... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Competition, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2023-10-21 14:14:16 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

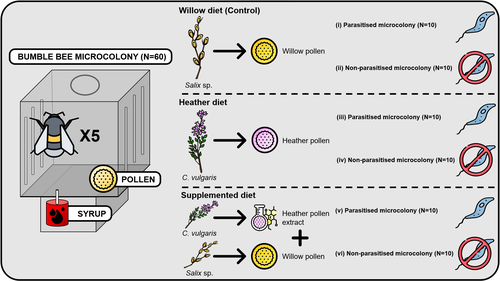

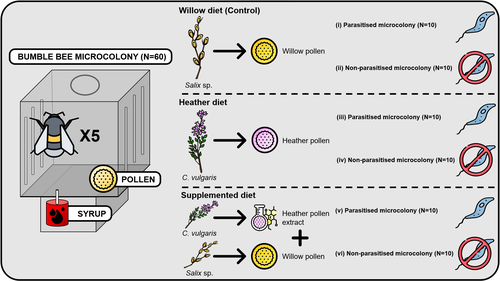

Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble beesClément Tourbez, Irène Semay, Apolline Michel, Denis Michez, Pascal Gerbaux, Antoine Gekière, Maryse Vanderplanck https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8192036The importance of understanding bee nutritionRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Cristina Botías and 1 anonymous reviewer

Contrasting with the great alarm on bee declines, it is astonishing how little basic biology we know about bees, including on abundant and widespread species that are becoming model species. Plant-pollinator relationships are one of the cornerstones of bee ecology, and researchers are increasingly documenting bees' diets. However, we rarely know which effects feeding on different flowers has on bees' health. This paper (Tourbez et al. 2023) uses an elegant experimental setting to test the effect of heather pollen on bumblebees' (Bombus terrestris) reproductive success. This is a timely question as heather is frequently used by bumblebees, and its nectar has been reported to reduce parasite infections. In fact, it has been suggested that bumblebees can medicate themselves when infected (Richardson et al. 2014), and the pollen of some Asteraceae has been shown to help them fight parasites (Gekière et al. 2022). The starting hypothesis is that heather pollen contains flavonoids that might have a similar effect. Unfortunately, Tourbez and collaborators do not support this hypothesis, showing a negative effect of heather pollen, in particular its flavonoids, in bumblebees offspring, and an increase in parasite loads when fed on flavonoids. This is important because it challenges the idea that many pollen and nectar chemical compounds might have a medicinal use, and force us to critically analyze the effect of chemical compounds in each particular case. The results open several questions, such as why bumblebees collect heather pollen, or in which concentrations or pollen mixes it is deleterious. A limitation of the study is that it uses micro-colonies, and extrapolating this to real-world conditions is always complex. Understanding bee declines require a holistic approach starting with bee physiology and scaling up to multispecies population dynamics. References Gekière, A., Semay, I., Gérard, M., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., & Vanderplanck, M. 2022. Poison or Potion: Effects of Sunflower Phenolamides on Bumble Bees and Their Gut Parasite. Biology, 11(4), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040545 Richardson, L.L., Adler, L.S., Leonard, A.S., Andicoechea, J., Regan, K.H., Anthony, W.E., Manson, J.S., & Irwin, R.E. 2015. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 282 (1803), 20142471. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2471 Tourbez, C., Semay, I., Michel, A., Michez, D., Gerbaux, P., Gekière A. & Vanderplanck, M. 2023. Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees. Zenodo, ver 3, reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8192036 | Heather pollen is not necessarily a healthy diet for bumble bees | Clément Tourbez, Irène Semay, Apolline Michel, Denis Michez, Pascal Gerbaux, Antoine Gekière, Maryse Vanderplanck | <p>There is evidence that specialised metabolites of flowering plants occur in both vegetative parts and floral resources (i.e., pollen and nectar), exposing pollinators to their biological activities. While such metabolites may be toxic to bees, ... |  | Botany, Chemical ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Pollination, Zoology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-04-10 21:22:34 | View | |

14 Jun 2024

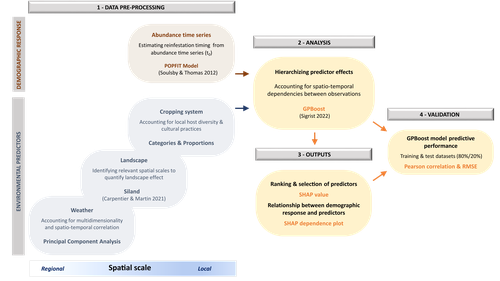

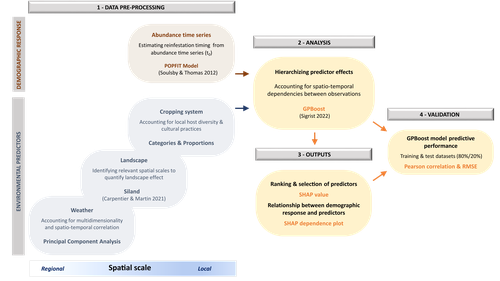

Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of Bactrocera dorsalis population growth in Senegalese orchardsCécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.10.566583Uncovering the ecology in big-data by hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effectsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Jianqiang SunAlong with the generalization of open-access practices, large, heterogeneous datasets are becoming increasingly available to ecologists (Farley et al. 2018). While such data offer exciting opportunities for unveiling original patterns and trends, they also raise new challenges regarding how to extract relevant information and actually improve our knowledge of complex ecological systems, beyond purely descriptive correlations (Dietze 2017, Farley et al. 2018). In this work, Caumette et al. (2024) develop an original ecoinformatics approach to relate multi-scale environmental factors to the temporal dynamics of a major pest in mango orchards. Their method relies on the recent tree-boosting method GPBoost (Sigrist 2022) to hierarchize the influence of environmental factors of heterogeneous nature (e.g., orchard composition and management; landscape structure; climate) on the emergence date of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. As boosting methods allows the analysis of high-dimensional data, they are particularly adapted to the exploration of such datasets, to uncover unexpected, potentially complex dependencies between ecological dynamics and multiple environmental factors (Farley et al. 2018). In this article, Caumette et al. (2024) make a special effort to guide the reader step by step through their complex analysis pipeline to make it broadly understandable to the average ecologist, which is no small feat. I particularly welcome this commitment, as making new, cutting-edge analytical methods accessible to a large community of science practitioners with varying degrees of statistical or programming expertise is a major challenge for the future of quantitative ecology. The main result of Caumette et al. (2024) is that temperature and humidity conditions both at the local and regional scales are the main predictors of B. dorsalis emergence date, while orchard management practices seem to have relatively little influence. This suggests that favourable climatic conditions may allow the persistence of small populations of B. dorsalis over the dry season, which may then act as a propagule source for early re-infestations. However, as the authors explain, the resulting regression model is not designed for predictive purposes and should not at this stage be used for decision-making in pest management. Its main interest rather resides in identifying potential key factors favoring early infestations of B. dorsalis, and help focusing future experimental field studies on the most relevant levers for integrated pest management in mango orchards. In a wider perspective, this work also provides a convincing proof-of-concept for the use of boosting methods to identify the most influential factors in large, multivariate datasets in a variety of ecological systems. It is also crucial to keep in mind that the current exponential growth in high-throughput environmental data (Lucivero 2020) could quickly come into conflict with the need to reduce the environmental footprint of research (Mariette et al. 2022). In this context, robust and accessible methods for extracting and exploiting all the information available in already existing datasets might prove essential to a sustainable pursuit of science. References Dietze MC. 2017. Ecological Forecasting. Princeton University Press Mariette J, Blanchard O, Berné O, Aumont O, Carrey J, Ligozat A-L, Lellouch E, Roche P-E, Guennebaud G, Thanwerdas J, Bardou P, Salin G, Maigne E, Servan S, Ben-Ari T 2022. An open-source tool to assess the carbon footprint of research. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ac84a4 | Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of *Bactrocera dorsalis* population growth in Senegalese orchards | Cécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier | <p>Implementing integrated pest management programs to limit agricultural pest damage requires an understanding of the interactions between the environmental variability and population demographic processes. However, identifying key environmental ... |  | Demography, Landscape ecology, Statistical ecology | Elodie Vercken | 2023-12-11 17:02:08 | View | |

07 Jun 2023

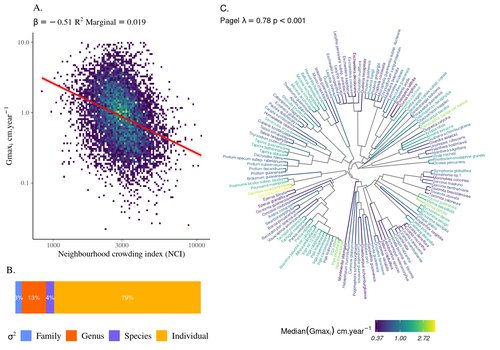

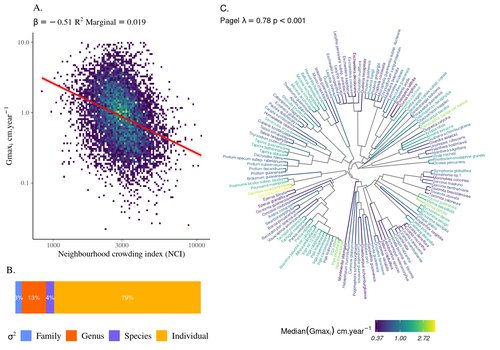

High intraspecific growth variability despite strong evolutionary heritage in a neotropical forestSylvain Schmitt, Bruno Hérault, Géraldine Derroire https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.27.501745Environmental and functional determinants of tree performance in a neotropical forest: the imprint of evolutionary legacy on growth strategiesRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Camille Girard and Jelena Pantel based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Camille Girard and Jelena Pantel

The hyperdiverse tropical forests have long fascinated ecologists because the fact that so many species persist at a low density at a local scale remains hard to explain. Both niche-based and neutral hypotheses have been tested, primarily based on analyzing the taxonomic composition of tropical forest plots (Janzen 1970; Hubbell 2001). Studies of the functional and phylogenetic structure of tropical tree communities have further aimed to better assess the importance of niche-based processes. For instance, Baraloto et al. (2012) found that co-occurring species were functionally and phylogenetically more similar in a neotropical forest, suggesting a role of environmental filtering. Likewise, Schmitt et al. (2021) found the influence of environmental filtering on the functional composition of an Indian rainforest. Yet these studies evidenced non-random trait-environment association based on the composition of assemblages only (in terms of occurrences and abundances). A major challenge remains to further address whether and how tree performance varies among species and individuals in tropical forests. Functional traits are related to components of individual fitness (Violle et al. 2007). Recently, more and more emphasis has been put on examining the relationship between functional trait values and demographic parameters (Salguero-Gómez et al. 2018), in order to better understand how functional trait values determine species population dynamics and abundances in assemblages. Fortunel et al. (2018) found an influence of functional traits on species growth variation related to topography, and less clearly to neighborhood density (crowding). Poorter et al. (2018) observed 44% of trait variation within species in a neotropical forest. Although individual trait values would be expected to be better predictors of performance than average values measured at the species level, Poorter et al still found a poor relationship. Schmitt et al. (2023) examined how abiotic conditions and biotic interactions (considering neighborhood density) influenced the variation of individual potential tree growth, in a tropical forest plot located in French Guiana. They also considered the link between species-averaged values of growth potential and functional traits. Schmitt et al. (2023) found substantial variation in growth potential within species, that functional traits explained 40% of the variation of species-averaged growth and, noticeably, that the taxonomic structure (used as random effect in their model) explained a third of the variation in individual growth. Although functional traits of roots, wood and leaves could predict a significant part of species growth potential, much variability of tree growth occurred within species. Intraspecific trait variation can thus be huge in response to changing abiotic and biotic contexts across individuals. The information on phylogenetic relationships can still provide a proxy of the integrated phenotypic variation that is under selection across the phylogeny, and determine a variation in growth strategies among individuals. The similarity of the phylogenetic structure suggests a joint selection of these growth strategies and related functional traits during events of convergent evolution. Baraloto et al. (2012) already noted that phylogenetic distance can be a proxy of niche overlap in tropical tree communities. Here, Schmitt et al. further demonstrate that evolutionary heritage is significantly related to individual growth variation, and plead for better acknowledging this role in future studies. While the role of fitness differences in tropical tree community dynamics remained to be assessed, the present study provides new evidence that individual growth does vary depending on evolutionary relationships, which can reflect the roles of selection and adaptation on growth strategies. Therefore, investigating both the influence of functional traits and phylogenetic relationships on individual performance remains a promising avenue of research, for functional and community ecology in general. REFERENCES Baraloto, Christopher, Olivier J. Hardy, C. E. Timothy Paine, Kyle G. Dexter, Corinne Cruaud, Luke T. Dunning, Mailyn-Adriana Gonzalez, et al. 2012. « Using functional traits and phylogenetic trees to examine the assembly of tropical tree communities ». Journal of Ecology, 100: 690‑701. | High intraspecific growth variability despite strong evolutionary heritage in a neotropical forest | Sylvain Schmitt, Bruno Hérault, Géraldine Derroire | <p style="text-align: justify;">Individual tree growth is a key determinant of species performance and a driver of forest dynamics and composition. Previous studies on tree growth unravelled the variation in species growth as a function of demogra... |  | Community ecology, Demography, Population ecology | François Munoz | Jelena Pantel, David Murray-Stoker | 2022-08-01 14:29:04 | View |

22 Mar 2021

Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore speciesBastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544Plants preserve the ghost of competition past for herbivores, but mothers don’t careRecommended by Sara Magalhães based on reviews by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-PereiraSome biological hypotheses are widely popular, so much so that we tend to forget their original lack of success. This is particularly true for hypotheses with catchy names. The ‘Ghost of competition past’ is part of the title of a paper by the great ecologist, JH Connell, one of the many losses of 2020 (Connell 1980). The hypothesis states that, even though we may not detect competition in current populations, their traits and distributions may be shaped by past competition events. Although this hypothesis has known a great success in the ecological literature, the original paper actually ends with “I will no longer be persuaded by such invoking of "the Ghost of Competition Past"”. Similarly, the hypothesis that mothers of herbivores choose host plants where their offspring will have a higher fitness was proposed by John Jaenike in 1978 (Jaenike 1978), and later coined the ‘mother knows best’ hypothesis. The hypothesis was readily questioned or dismissed: “Mother doesn't know best” (Courtney and Kibota 1990), or “Does mother know best?” (Valladares and Lawton 1991), but remains widely popular. It thus seems that catchy names (and the intuitive ideas behind them) have a heuristic value that is independent from the original persuasion in these ideas and the accumulation of evidence that followed it. The paper by Castagneryol et al. (2021) analyses the preference-performance relationship in the box tree moth (BTM) Cydalima perspectalis, after defoliation of their host plant, the box tree, by conspecifics. It thus has bearings on the two previously mentioned hypotheses. Specifically, they created an artificial population of potted box trees in a greenhouse, in which 60 trees were infested with BTM third instar larvae, whereas 61 were left uninfested. One week later, these larvae were removed and another three weeks later, they released adult BTM females and recorded their host choice by counting egg clutches laid by these females on the plants. Finally, they evaluated the effect of previously infested vs uninfested plants on BTM performance by measuring the weight of third instar larvae that had emerged from those eggs. This experimental design was adopted because BTM is a multivoltine species. When the second generation of BTM arrives, plants have been defoliated by the first generation and did not fully recover. Indeed, Castagneryol et al. (2021) found that larvae that developed on previously infested plants were much smaller than those developing on uninfested plants, and the same was true for the chrysalis that emerged from those larvae. This provides unequivocal evidence for the existence of a ghost of competition past in this system. However, the existence of this ghost still does not result in a change in the distribution of BTM, precisely because mothers do not know best: they lay as many eggs on plants previously infested than on uninfested plants. The demonstration that the previous presence of a competitor affects the performance of this herbivore species confirms that ghosts exist. However, whether this entails that previous (interspecific) competition shapes species distributions, as originally meant, remains an open question. Species phenology may play an important role in exposing organisms to the ghost, as this time-lagged competition may have been often overlooked. It is also relevant to try to understand why mothers don’t care in this, and other systems. One possibility is that they will have few opportunities to effectively choose in the real world, due to limited dispersal or to all plants being previously infested. References Castagneyrol, B., Halder, I. van, Kadiri, Y., Schillé, L. and Jactel, H. (2021) Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.228544, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544 Connell, J. H. (1980). Diversity and the coevolution of competitors, or the ghost of competition past. Oikos, 131-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 Courtney, S. P. and Kibota, T. T. (1990) in Insect-plant interactions (ed. Bernays, E.A.) 285-330. Jaenike, J. (1978). On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects. Theoretical population biology, 14(3), 350-356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6 Valladares, G., and Lawton, J. H. (1991). Host-plant selection in the holly leaf-miner: does mother know best?. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 227-240. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/5456

| Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species | Bastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel | <p>Conspecific insect herbivores co-occurring on the same host plant interact both directly through interference competition and indirectly through exploitative competition, plant-mediated interactions and enemy-mediated interactions. However, the... |  | Competition, Herbivory, Zoology | Sara Magalhães | 2020-08-03 15:50:23 | View | |

19 Dec 2020

Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.)Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.986984A new member of the morphometrics jungle to better monitor vulnerable lagoonsRecommended by Vincent Bonhomme based on reviews by Julien Claude and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the recent years, morphometrics, the quantitative description of shape and its covariation [1] gained considerable momentum in evolutionary ecology. Using the form of organisms to describe, classify and try to understand their diversity can be traced back at least to Aristotle. More recently, two successive revolutions rejuvenated this idea [1–3]: first, a proper mathematical refoundation of the theory of shape, then a technical revolution in the apparatus able to acquire raw data. By using a feature extraction method and planning its massive use on data acquired by aerial drones, the study by Lacaux and colleagues [4] retraces this curse of events. The sample sizes studied here were too low to allow finer-grained ecophysiological investigations. That being said, the proof-of-concept is convincing and this paper paths the way for an operational and innovative approach to the ecological monitoring of sensible aquatic ecosystems. References [1] Kendall, D. G. (1989). A survey of the statistical theory of shape. Statistical Science, 87-99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177012589 | Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) | Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry | <p>Variations of the animal body plan morphology and morphometry can be used as prognostic tools of their habitat quality. The potential of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) as a new model organism has been poorly tested. However, as a tetramerous... |  | Morphometrics | Vincent Bonhomme | 2020-03-18 17:40:51 | View | |

30 Sep 2020

How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessmentFlorence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.02.129536Citizen science contributes to SDM validationRecommended by Francisco Lloret based on reviews by Maria Angeles Perez-Navarro and 1 anonymous reviewerCitizen science is becoming an important piece for the acquisition of scientific knowledge in the fields of natural sciences, and particularly in the inventory and monitoring of biodiversity (McKinley et al. 2017). The information generated with the collaboration of citizens has an evident importance in conservation, by providing information on the state of populations and habitats, helping in mitigation and restoration actions, and very importantly contributing to involve society in conservation (Brown and Williams 2019).

An obvious advantage of these initiatives is the ability to mobilize human resources on a large territorial scale and in the medium term, which would otherwise be difficult to finance. The resulting increasing information then can be processed with advanced computational techniques (Hochachka et al 2012; Kelling et al. 2015), thus improving our interpretation of the distribution of species. Specifically, the ability to obtain information on a large territorial scale can be integrated into studies based on Species Distribution Models SDMs. One of the common problems with SDMs is that they often work from species occurrences that have been opportunistically recorded, either by professionals or amateurs. A great challenge for data obtained from non-professional citizens, however, remains to ensure its standardization and quality (Kosmala et al. 2016). This requires a clear and effective design, solid volunteer training, and a high level of coordination that turns out to be complex (Brown and Williams 2019). Finally, it is essential to perform a quality validation following scientifically recognized standards, since they are often conditioned by errors and biases in obtaining information (Bird et al. 2014). There are two basic approaches to obtain the necessary data for this validation: getting it from an external source (external validation), or allocating a part of the database itself (internal validation or cross-validation) to this function. References [1] Bird TJ et al. (2014) Statistical solutions for error and bias in global citizen science datasets. Biological Conservation 173: 144-154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.07.037 | How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessment | Florence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon | <p>Species distribution models (SDM) have been increasingly developed in recent years but their validity is questioned. Their assessment can be improved by the use of independent data but this can be difficult to obtain and prohibitive to collect.... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Francisco Lloret | 2020-06-03 09:36:34 | View | ||

19 Mar 2024

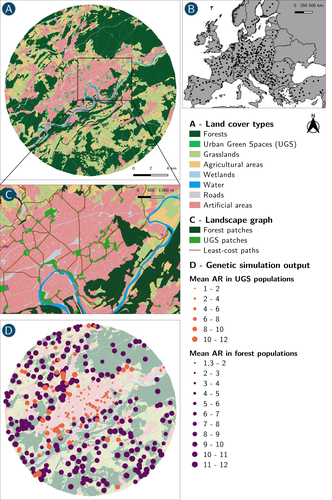

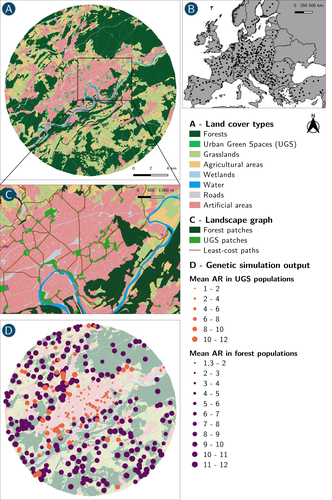

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle