Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Jan 2024

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonisAlexius Folk, Adele Mennerat https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695Marking invertebrates using RFID tagsRecommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer

Guiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically. The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it. References Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013 Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008. Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695 Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082 Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900 | Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse *Lepeophtheirus salmonis* | Alexius Folk, Adele Mennerat | <p style="text-align: justify;">Monitoring individuals within populations is a cornerstone in evolutionary ecology, yet individual tracking of invertebrates and particularly parasitic organisms remains rare. To address this gap, we describe here a... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Marine ecology, Parasitology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-09-04 15:25:08 | View | |

27 Nov 2023

Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted TreesWilliam Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443Gradient Boosted Trees can deliver more than accurate ecological predictionsRecommended by Timothée Poisot based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne diseases are an important burden on public health all over the globe, making accurate forecasts of tick population a key ingredient in a successful public health strategy. Over long time scales, tick populations can undergo complex dynamics, as they are sensitive to many non-linear effects due to the complex relationships between ticks and the relevant (numerical) features of their environment. But luckily, capturing complex non-linear responses is a task that machine learning thrives on. In this contribution, Manley et al. (2023) explore the use of Gradient Boosted Trees to predict the distribution (presence/absence) and abundance of ticks across New York state. This is an interesting modelling challenge in and of itself, as it looks at the same ecological question as an instance of a classification problem (presence/absence) or of a regression problem (abundance). In using the same family of algorithm for both, Manley et al. (2023) provide an interesting showcase of the versatility of these techniques. But their article goes one step further, by setting up a multi-class categorical model that estimates jointly the presence and abundance of a population. I found this part of the article particularly elegant, as it provides an intermediate modelling strategy, in between having two disconnected models for distribution and abundance, and having nested models where abundance is only predicted for the present class (see e.g. Boulangeat et al., 2012, for a great description of the later). One thing that Manley et al. (2023) should be commended for is their focus on opening up the black box of machine learning techniques. I have never believed that ML models are more inherently opaque than other families of models, but the focus in this article on explainable machine learning shows how these models might, in fact, bring us closer to a phenomenological understanding of the mechanisms underpinning our observations. There is also an interesting discussion in this article, on the rate of false negatives in the different models that are being benchmarked. Although model selection often comes down to optimizing the overall quality of the confusion matrix (for distribution models, anyway), depending on the type of information we seek to extract from the model, not all types of errors are created equal. If the purpose of the model is to guide actions to control vectors of human pathogens, a false negative (predicting that the vector is absent at a site where it is actually present) is a potentially more damaging outcome, as it can lead to the vector population (and therefore, potentially, transmission) increasing unchecked. References

Boulangeat I, Gravel D, Thuiller W. Accounting for dispersal and biotic interactions to disentangle the drivers of species distributions and their abundances: The role of dispersal and biotic interactions in explaining species distributions and abundances. Ecol Lett. 2012;15: 584-593. Manley W, Tran T, Prusinski M, Brisson D. (2023) Modeling tick populations: An ecological test case for gradient boosted trees. bioRxiv, 2023.03.13.532443, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.13.532443 | Modeling Tick Populations: An Ecological Test Case for Gradient Boosted Trees | William Manley, Tam Tran, Melissa Prusinski, Dustin Brisson | <p style="text-align: justify;">General linear models have been the foundational statistical framework used to discover the ecological processes that explain the distribution and abundance of natural populations. Analyses of the rapidly expanding ... | Parasitology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Timothée Poisot | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2023-03-23 23:41:17 | View | |

28 Apr 2023

Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical floraJulien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127Pollination-herbivory by weevils claiming for recognition: the Cinderella among pollinatorsRecommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Susan Kirmse, Carlos Eduardo Nunes and 2 anonymous reviewersSince Charles Darwin times, and probably earlier, naturalists have been eager to report the rarest pollinators being discovered, and this still happens even in recent times; e.g., increased evidence of lizards, cockroaches, crickets or earwigs as pollinators (Suetsugu 2018, Komamura et al. 2021, de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023), shifts to invasive animals as pollinators, including passerine birds and rats (Pattemore & Wilcove 2012), new amazing cases of mimicry in pollination, such as “bleeding” flowers that mimic wounded insects (Heiduk et al., 2023) or even the possibility that a tree frog is reported for the first time as a pollinator (de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023). This is in part due to a natural curiosity of humans about rarity, which pervades into scientific insight (Gaston 1994). Among pollinators, the apparent rarity of some interaction types is sometimes a symptom of a lack of enough inquiry. This seems to be the case of weevil pollination, given that these insects are widely recognized as herbivores, particularly those that use plant parts to nurse their breed and never were thought they could act also as mutualists, pollinating the species they infest. This is known as a case of brood site pollination mutualism (BSPM), which also involves an antagonistic counterpart (herbivory) to which plants should face. This is the focus of the manuscript (Haran et al. 2023) we are recommending here. There is wide treatment of this kind of pollination in textbooks, albeit focused on yucca-yucca moth and fig-fig wasp interactions due to their extreme specialization (Pellmyr 2003, Kjellberg et al. 2005), and more recently accompanied by Caryophyllaceae-moth relationship (Kephart et al. 2006). Here we find a detailed review that shows that the most diverse BSPM, in terms of number of plant and pollinator species involved, is that of weevils in the tropics. The mechanism of BSPM does not involve a unique morphological syndrome, as it is mostly functional and thus highly dependent on insect biology (Fenster & al. 2004), whereas the flower phenotypes are highly divergent among species. Probably, the inconspicuous nature of the interaction, and the overwhelming role of weevils as seed predators, even as pests, are among the causes of the neglection of weevils as pollinators, as it could be in part the case of ants as pollinators (de Vega et al. 2014). The paper by Haran et al (2023) comes to break this point. Thus, the rarity of weevil pollination in former reports is not a consequence of an anecdotical nature of this interaction, even for the BSPM, according to the number of cases the authors are reporting, both in terms of plant and pollinator species involved. This review has a classical narrative format which involves a long text describing the natural history behind the cases. It is timely and fills the gap for this important pollination interaction for biodiversity and also for economic implications for fruit production of some crops. Former reviews have addressed related topics on BSPM but focused on other pollinators, such as those mentioned above. Besides, the review put much effort into the animal side of the interaction, which is not common in the pollination literature. Admittedly, the authors focus on the detailed description of some paradigmatic cases, and thereafter suggest that these can be more frequently reported in the future, based on varied evidence from morphology, natural history, ecology, and distribution of alleged partners. This procedure was common during the development of anthecology, an almost missing term for floral ecology (Baker 1983), relying on accumulative evidence based on detailed observations and experiments on flowers and pollinators. Currently, a quantitative approach based on the tools of macroecological/macroevolutionary analyses is more frequent in reviews. However, this approach requires a high amount of information on the natural history of the partnership, which allows for sound hypothesis testing. By accumulating this information, this approach allows the authors to pose specific questions and hypotheses which can be tested, particularly on the efficiency of the systems and their specialization degree for both the plants and the weevils, apparently higher for the latter. This will guarantee that this paper will be frequently cited by floral ecologists and evolutionary biologists and be included among the plethora of floral syndromes already described, currently based on more explicit functional grounds (Fenster et al. 2004). In part, this is one of the reasons why the sections focused on future prospects is so large in the review. I foresee that this mutualistic/antagonistic relationship will provide excellent study cases for the relative weight of these contrary interactions among the same partners and its relationship with pollination specialization-generalization and patterns of diversification in the plants and/or the weevils. As new studies are coming, it is possible that BSPM by weevils appears more common in non-tropical biogeographical regions. In fact, other BSPM are not so uncommon in other regions (Prieto-Benítez et al. 2017). In the future, it would be desirable an appropriate testing of the actual effect of phylogenetic niche conservatism, using well known and appropriately selected BSPM cases and robust phylogenies of both partners in the mutualism. Phylogenetic niche conservatism is a central assumption by the authors to report as many cases as possible in their review, and for that they used taxonomic relatedness. As sequence data and derived phylogenies for large numbers of vascular plant species are becoming more frequent (Jin & Quian 2022), I would recommend the authors to perform a comparative analysis using this phylogenetic information. At least, they have included information on phylogenetic relatedness of weevils involved in BSPM which allow some inferences on the multiple origins of this interaction. This is a good start to explore the drivers of these multiple origins through the lens of comparative biology. References Baker HG (1983) An Outline of the History of Anthecology, or Pollination Biology. In: L Real (ed). Pollination Biology. Academic Press. de-Oliveira-Nogueira CH, Souza UF, Machado TM, Figueiredo-de-Andrade CA, Mónico AT, Sazima I, Sazima M, Toledo LF (2023). Between fruits, flowers and nectar: The extraordinary diet of the frog Xenohyla truncate. Food Webs 35: e00281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2023.e00281 Fenster CB W, Armbruster S, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD (2004). Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35: 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347 Gaston KJ (1994). What is rarity? In KJ Gaston (ed): Rarity. Population and Community Biology Series, vol 13. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0701-3_1 Haran J, Kergoat GJ, Bruno, de Medeiros AS (2023) Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora. hal. 03780127, version 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127 Heiduk A, Brake I, Shuttleworth A, Johnson SD (2023) ‘Bleeding’ flowers of Ceropegia gerrardii (Apocynaceae-Asclepiadoideae) mimic wounded insects to attract kleptoparasitic fly pollinators. New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18888 Jin, Y., & Qian, H. (2022). V. PhyloMaker2: An updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity, 44(4), 335-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.05.005 Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Hossaert-Mckey M, Rasplus JY (2005). Biology, ecology, and evolution of fig-pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). In: A. Raman et al (eds) Biology, ecology and evolution of gall-inducing arthropods 2, 539-572. Science Publishers, Enfield. Komamura R, Koyama K, Yamauchi T, Konno Y, Gu L (2021). Pollination contribution differs among insects visiting Cardiocrinum cordatum flowers. Forests 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040452 Pattemore DE, Wilcove DS (2012) Invasive rats and recent colonist birds partially compensate for the loss of endemic New Zealand pollinators. Proc. R. Soc. B 279: 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.2036 Pellmyr O (2003) Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 90: 35-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524 Prieto-Benítez S, Yela JL, Giménez-Benavides L (2017) Ten years of progress in the study of Hadena-Caryophyllaceae nursery pollination. A review in light of new Mediterranean data. Flora, 232, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2017.02.004 Suetsugu K (2019) Social wasps, crickets and cockroaches contribute to pollination of the holoparasitic plant Mitrastemon yamamotoi (Mitrastemonaceae) in southern Japan. Plant Biology 21 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12889 | Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora | Julien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros | <p style="text-align: justify;">In tropical environments, and especially tropical rainforests, a major part of pollination services is provided by diverse insect lineages. Unbeknownst to most, beetles, and more specifically hyperdiverse weevils (C... | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Pollination, Tropical ecology | Juan Arroyo | 2022-09-28 11:54:37 | View | ||

29 Sep 2023

MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modellingOndřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.05.531080A deep learning model to unlock secrets of animal movement and behaviourRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

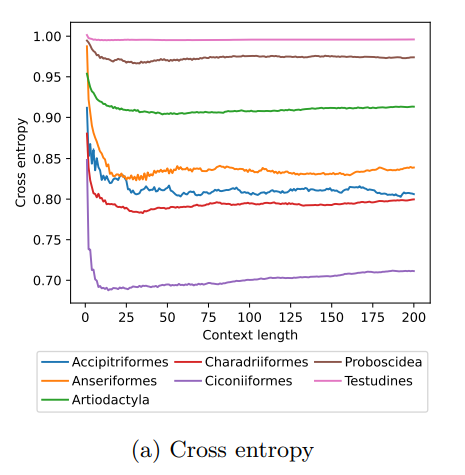

The study of animal movement is essential for understanding their behaviour and how ecological or global changes impact their routines [1]. Recent technological advancements have improved the collection of movement data [2], but limited statistical tools have hindered the analysis of such data [3–5]. Animal movement is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by internal knowledge and memory, which are challenging to observe directly [6,7]. Routine movement behaviours and the incorporation of memory into models remain understudied. Researchers have developed ‘MoveFormer’ [8], a deep learning-based model that predicts future movements based on past context, addressing these challenges and offering insights into the importance of different context lengths and information types. The model has been applied to a dataset of over 1,550 trajectories from various species, and the authors have made the MoveFormer source code available for further research. Inspired by the step-selection framework and efforts to quantify uncertainty in movement predictions, MoveFormer leverages deep learning, specifically the Transformer architecture, to encode trajectories and understand how past movements influence current and future ones – a critical question in movement ecology. The results indicate that integrating information from a few days to two or three weeks before the movement enhances predictions. The model also accounts for environmental predictors and offers insights into the factors influencing animal movements. Its potential impact extends to conservation, comparative analyses, and the generalisation of uncertainty-handling methods beyond ecology, with open-source code fostering collaboration and innovation in various scientific domains. Indeed, this method could be applied to analyse other kinds of movements, such as arm movements during tool use [9], pen movements, or eye movements during drawing [10], to better understand anticipation in actions and their intentionality. References 1. Méndez, V.; Campos, D.; Bartumeus, F. Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous Diffusion, Front Propagation and Random Searches; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-39009-8. | MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modelling | Ondřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus | <p style="text-align: justify;">The movement of animals is a central component of their behavioural strategies. Statistical tools for movement data analysis, however, have long been limited, and in particular, unable to account for past movement i... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Habitat selection | Cédric Sueur | 2023-03-22 16:32:14 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

09 Dec 2019

Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive successAinhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus https://doi.org/10.1101/629931Improving our knowledge of species interaction networksRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers

Ecosystems shelter a huge number of species, continuously interacting. Each species interact in various ways, with trophic interactions, but also non-trophic interactions, not mentioning the abiotic and anthropogenic interactions. In particular, pollination, competition, facilitation, parasitism and many other interaction types are simultaneously present at the same place in terrestrial ecosystems [1-2]. For this reason, we need today to improve our understanding of such complex interaction networks to later anticipate their responses. This program is a huge challenge facing ecologists and they today join their forces among experimentalists, theoreticians and modelers. While some of us struggle in theoretical and modeling dimensions [3-4], some others perform brilliant works to observe and/or experiment on the same ecological objects [5-6]. References [1] Campbell, C., Yang, S., Albert, R., and Shea, K. (2011). A network model for plant–pollinator community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(1), 197-202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008204108 | Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive success | Ainhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus | <p>Declines in pollinator diversity and abundance have been reported across different regions, with implications for the reproductive success of plant species. However, research has focused primarily on pairwise plant-pollinator interactions, larg... |  | Ecosystem functioning, Interaction networks, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | Nicolas Deguines | 2019-05-07 17:03:23 | View |

12 Jan 2022

No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria MosquitoesSerge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542The search for sex pheromones in malaria mosquitoesRecommended by Niels Verhulst based on reviews by Marcelo Lorenzo and 1 anonymous reviewerPheromones are used by many insects to find the opposite sex for mating. Especially for nocturnal mosquitoes it seems logical that such pheromones exist as they can only partly rely on visual cues when flying at night. The males of many mosquito species form swarms and conspecific females fly into these swarms to mate. The two sibling species of malaria mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii coexist and both form swarms consisting of only one species. Although hybrids can be produced, these hybrids are rarely found in nature. In the study presented by Poda and colleagues (2022) it was tested if long-range sex pheromones exist in these two mosquito sibling species. In a previous study by Mozūraites et al. (2020), five compounds (acetoin, sulcatone, octanal, nonanal and decanal) were identified that induced male swarming and increase mating success. Interestingly these compounds are frequently found in nature and have been shown to play a role in sugar feeding or host finding of An. gambiae. In the recommended study performed by Poda et al. (2022) no evidence of long-range sex pheromones in A. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii was found. The discrepancy between the two studies is difficult to explain but some of the methods varied between studies. Mozūraites et al. (2020) for example, collected odours from mosquitoes in small 1l glass bottles, where swarming is questionable, while in the study of Poda et al. (2022) 50 x 40 x 40 cm cages were used and swarming observed, although most swarms are normally larger. On the other hand, some of the analytical techniques used in the Mozūraites et al. (2020) study were more sensitive while others were more sensitive in the Poda et al. (2022) study. Because it is difficult to prove that something does not exist, the authors nicely indicate that “an absence of evidence is not an evidence of absence” (Poda et al., 2022). Nevertheless, recently colonized species were tested in large cage setups where swarming was observed and various methods were used to try to detect sex pheromones. No attraction to the volatile blend from male swarms was detected in an olfactometer, no antenna-electrophysiological response of females to male swarm volatile compounds was detected and no specific male swarm volatile was identified. This study will open the discussion again if (sex) pheromones play a role in swarming and mating of malaria mosquitoes. Future studies should focus on sensitive real-time volatile analysis in mating swarms in large cages or field settings. In comparison to moths for example that are very sensitive to very specific pheromones and attract from a large distance, such a long-range specific pheromone does not seem to exist in these mosquito species. Acoustic and visual cues have been shown to be involved in mating (Diabate et al., 2003; Gibson and Russell, 2006) and especially at long distances, visual cues are probably important for the detection of these swarms. References Diabate A, Baldet T, Brengues C, Kengne P, Dabire KR, Simard F, Chandre F, Hougard JM, Hemingway J, Ouedraogo JB, Fontenille D (2003) Natural swarming behaviour of the molecular M form of Anopheles gambiae. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97, 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80110-4 Gibson G, Russell I (2006) Flying in Tune: Sexual Recognition in Mosquitoes. Current Biology, 16, 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.053 Mozūraitis, R., Hajkazemian, M., Zawada, J.W., Szymczak, J., Pålsson, K., Sekar, V., Biryukova, I., Friedländer, M.R., Koekemoer, L.L., Baird, J.K., Borg-Karlson, A.-K., Emami, S.N. (2020) Male swarming aggregation pheromones increase female attraction and mating success among multiple African malaria vector mosquito species. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1264-9 Poda, S.B., Buatois, B., Lapeyre, B., Dormont, L., Diabate, A., Gnankine, O., Dabire, R.K., Roux, O. (2022) No evidence for long-range male sex pheromones in two malaria mosquitoes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.05.187542, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542 | No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria Mosquitoes | Serge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Cues involved in mate seeking and recognition prevent hybridization and can be involved in speciation processes. In malaria mosquitoes, females of the two sibling species <em>Anopheles gambiae</em> s.s. and <em>An. ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Chemical ecology | Niels Verhulst | 2021-04-26 12:28:36 | View | |

18 Dec 2020

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islandsManuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamicsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey

Polar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). References Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043 | Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands | Manuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault | <p>Aim Here, we aim to: (i) investigate the local effect of environmental and human-related factors on alien plant invasion in sub-Antarctic islands; (ii) explore the relationship between alien species features and their dependence on anthropogeni... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2020-07-21 21:13:08 | View | |

12 May 2020

On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendationsDavid Murray-Stoker https://doi.org/10.1101/611939A stronger statistical test of stream restoration experimentsRecommended by Karl Cottenie based on reviews by Eric Harvey and Mariana Perez RochaThe metacommunity framework acknowledges that local sites are connected to other sites through dispersal, and that these connectivity patterns can influence local dynamics [1]. This framework is slowly moving from a framework that guides fundamental research to being actively applied in for instance a conservation context (e.g. [2]). Swan and Brown [3,4] analyzed the results of a suite of experimental manipulations in headwater and mainstem streams on invertebrate community structure in the context of the metacommunity concept. This was an important contribution to conservation ecology. References [1] Leibold, M. A., Holyoak, M., Mouquet, N. et al. (2004). The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi‐scale community ecology. Ecology letters, 7(7), 601-613. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x | On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendations | David Murray-Stoker | <p>Swan and Brown (2017) recently addressed the effects of restoration on stream communities under the meta-community framework. Using a combination of headwater and mainstem streams, Swan and Brown (2017) evaluated how position within a stream ne... |  | Community ecology, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Karl Cottenie | 2019-09-21 22:12:57 | View | |

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle