ARROYO Juan

- Plant Biology and Ecology, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

- Biodiversity, Biogeography, Botany, Conservation biology, Evolutionary ecology, Phylogeny & Phylogeography, Pollination, Species distributions

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Review: 1

Recommendation: 1

Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora

Pollination-herbivory by weevils claiming for recognition: the Cinderella among pollinators

Recommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Susan Kirmse, Carlos Eduardo Nunes and 2 anonymous reviewersSince Charles Darwin times, and probably earlier, naturalists have been eager to report the rarest pollinators being discovered, and this still happens even in recent times; e.g., increased evidence of lizards, cockroaches, crickets or earwigs as pollinators (Suetsugu 2018, Komamura et al. 2021, de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023), shifts to invasive animals as pollinators, including passerine birds and rats (Pattemore & Wilcove 2012), new amazing cases of mimicry in pollination, such as “bleeding” flowers that mimic wounded insects (Heiduk et al., 2023) or even the possibility that a tree frog is reported for the first time as a pollinator (de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023). This is in part due to a natural curiosity of humans about rarity, which pervades into scientific insight (Gaston 1994). Among pollinators, the apparent rarity of some interaction types is sometimes a symptom of a lack of enough inquiry. This seems to be the case of weevil pollination, given that these insects are widely recognized as herbivores, particularly those that use plant parts to nurse their breed and never were thought they could act also as mutualists, pollinating the species they infest. This is known as a case of brood site pollination mutualism (BSPM), which also involves an antagonistic counterpart (herbivory) to which plants should face. This is the focus of the manuscript (Haran et al. 2023) we are recommending here. There is wide treatment of this kind of pollination in textbooks, albeit focused on yucca-yucca moth and fig-fig wasp interactions due to their extreme specialization (Pellmyr 2003, Kjellberg et al. 2005), and more recently accompanied by Caryophyllaceae-moth relationship (Kephart et al. 2006).

Here we find a detailed review that shows that the most diverse BSPM, in terms of number of plant and pollinator species involved, is that of weevils in the tropics. The mechanism of BSPM does not involve a unique morphological syndrome, as it is mostly functional and thus highly dependent on insect biology (Fenster & al. 2004), whereas the flower phenotypes are highly divergent among species. Probably, the inconspicuous nature of the interaction, and the overwhelming role of weevils as seed predators, even as pests, are among the causes of the neglection of weevils as pollinators, as it could be in part the case of ants as pollinators (de Vega et al. 2014). The paper by Haran et al (2023) comes to break this point.

Thus, the rarity of weevil pollination in former reports is not a consequence of an anecdotical nature of this interaction, even for the BSPM, according to the number of cases the authors are reporting, both in terms of plant and pollinator species involved. This review has a classical narrative format which involves a long text describing the natural history behind the cases. It is timely and fills the gap for this important pollination interaction for biodiversity and also for economic implications for fruit production of some crops. Former reviews have addressed related topics on BSPM but focused on other pollinators, such as those mentioned above. Besides, the review put much effort into the animal side of the interaction, which is not common in the pollination literature. Admittedly, the authors focus on the detailed description of some paradigmatic cases, and thereafter suggest that these can be more frequently reported in the future, based on varied evidence from morphology, natural history, ecology, and distribution of alleged partners. This procedure was common during the development of anthecology, an almost missing term for floral ecology (Baker 1983), relying on accumulative evidence based on detailed observations and experiments on flowers and pollinators. Currently, a quantitative approach based on the tools of macroecological/macroevolutionary analyses is more frequent in reviews. However, this approach requires a high amount of information on the natural history of the partnership, which allows for sound hypothesis testing. By accumulating this information, this approach allows the authors to pose specific questions and hypotheses which can be tested, particularly on the efficiency of the systems and their specialization degree for both the plants and the weevils, apparently higher for the latter. This will guarantee that this paper will be frequently cited by floral ecologists and evolutionary biologists and be included among the plethora of floral syndromes already described, currently based on more explicit functional grounds (Fenster et al. 2004). In part, this is one of the reasons why the sections focused on future prospects is so large in the review.

I foresee that this mutualistic/antagonistic relationship will provide excellent study cases for the relative weight of these contrary interactions among the same partners and its relationship with pollination specialization-generalization and patterns of diversification in the plants and/or the weevils. As new studies are coming, it is possible that BSPM by weevils appears more common in non-tropical biogeographical regions. In fact, other BSPM are not so uncommon in other regions (Prieto-Benítez et al. 2017). In the future, it would be desirable an appropriate testing of the actual effect of phylogenetic niche conservatism, using well known and appropriately selected BSPM cases and robust phylogenies of both partners in the mutualism. Phylogenetic niche conservatism is a central assumption by the authors to report as many cases as possible in their review, and for that they used taxonomic relatedness. As sequence data and derived phylogenies for large numbers of vascular plant species are becoming more frequent (Jin & Quian 2022), I would recommend the authors to perform a comparative analysis using this phylogenetic information. At least, they have included information on phylogenetic relatedness of weevils involved in BSPM which allow some inferences on the multiple origins of this interaction. This is a good start to explore the drivers of these multiple origins through the lens of comparative biology.

References

Baker HG (1983) An Outline of the History of Anthecology, or Pollination Biology. In: L Real (ed). Pollination Biology. Academic Press.

de-Oliveira-Nogueira CH, Souza UF, Machado TM, Figueiredo-de-Andrade CA, Mónico AT, Sazima I, Sazima M, Toledo LF (2023). Between fruits, flowers and nectar: The extraordinary diet of the frog Xenohyla truncate. Food Webs 35: e00281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2023.e00281

Fenster CB W, Armbruster S, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD (2004). Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35: 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347

Gaston KJ (1994). What is rarity? In KJ Gaston (ed): Rarity. Population and Community Biology Series, vol 13. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0701-3_1

Haran J, Kergoat GJ, Bruno, de Medeiros AS (2023) Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora. hal. 03780127, version 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127

Heiduk A, Brake I, Shuttleworth A, Johnson SD (2023) ‘Bleeding’ flowers of Ceropegia gerrardii (Apocynaceae-Asclepiadoideae) mimic wounded insects to attract kleptoparasitic fly pollinators. New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18888

Jin, Y., & Qian, H. (2022). V. PhyloMaker2: An updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity, 44(4), 335-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.05.005

Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Hossaert-Mckey M, Rasplus JY (2005). Biology, ecology, and evolution of fig-pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). In: A. Raman et al (eds) Biology, ecology and evolution of gall-inducing arthropods 2, 539-572. Science Publishers, Enfield.

Komamura R, Koyama K, Yamauchi T, Konno Y, Gu L (2021). Pollination contribution differs among insects visiting Cardiocrinum cordatum flowers. Forests 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040452

Pattemore DE, Wilcove DS (2012) Invasive rats and recent colonist birds partially compensate for the loss of endemic New Zealand pollinators. Proc. R. Soc. B 279: 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.2036

Pellmyr O (2003) Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 90: 35-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524

Prieto-Benítez S, Yela JL, Giménez-Benavides L (2017) Ten years of progress in the study of Hadena-Caryophyllaceae nursery pollination. A review in light of new Mediterranean data. Flora, 232, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2017.02.004

Suetsugu K (2019) Social wasps, crickets and cockroaches contribute to pollination of the holoparasitic plant Mitrastemon yamamotoi (Mitrastemonaceae) in southern Japan. Plant Biology 21 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12889

Review: 1

Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala

Water primerose (Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala) auto- and allogamy: an ecological perspective

Recommended by Antoine Vernay based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewerInvasive plant species are widely studied by the ecologist community, especially in wetlands. Indeed, alien plants are considered one of the major threats to wetland biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019). Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G.L.Nesom & Kartesz, 2000 (Lgh) is one of them and has received particular attention for a long time (Hieda et al., 2020; Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiebaut, 2013). The ecology of this invasive species and its effect on its biotic and abiotic environment has been studied in previous works. Different processes were demonstrated to explain their invasibility such as allelopathic interference (Dandelot et al., 2008), resource competition (Gérard et al., 2014), and high phenotypic plasticity (Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiébaut, 2013), to cite a few of them. However, although vegetative reproduction is a well-known invasive process for alien plants like Lgh (Glover et al., 2015), the sexual reproduction of this species is still unclear and may help to understand the Lgh population dynamics.

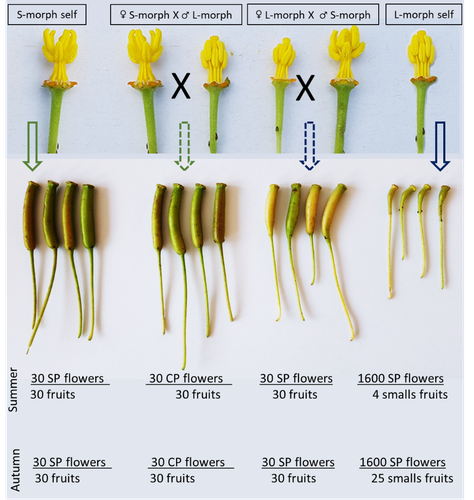

Portillo Lemus et al. (2021) showed that two floral morphs of Lgh co-exist in natura, involving self-compatibility for short-styled phenotype and self-incompatibility for long-styled phenotype processes. This new article (Portillo Lemus et al., 2022) goes further and details the underlying mechanisms of the sexual reproduction of the two floral morphs.

Complementing their previous study, the authors have described a late self-incompatible process associated with the long-styled morph, which authorized a small proportion of autogamy. Although this represents a small fraction of the L-morph reproduction, it may have a considerable impact on the L-morph population dynamics. Indeed, authors report that “floral morphs are mostly found in allopatric monomorphic populations (i.e., exclusively S-morph or exclusively L-morph populations)” with a large proportion of L-morph populations compared to S-morph populations in the field. It may seem counterintuitive as L-morph mainly relies on cross-fecundation.

Results show that L-morph autogamy mainly occurs in the fall, late in the reproduction season. Therefore, the reproduction may be ensured if no exogenous pollen reaches the stigma of L-morph individuals. It partly explains the large proportion of L-morph populations in the field.

Beyond the description of late-acting self-incompatibility, which makes the Onagraceae a third family of Myrtales with this reproductive adaptation, the study raises several ecological questions linked to the results presented in the article. First, it seems that even if autogamy is possible, Lgh would favour allogamy, even in S-morph, through the faster development of pollen tubes from other individuals. This may confer an adaptative and evolutive advantage for the Lgh, increasing its invasive potential. The article shows this faster pollen tube development in S-morph but does not test the evolutive consequences. It is an interesting perspective for future research. It would also be interesting to describe cellular processes which recognize and then influence the speed of the pollen tube. Second, the importance of sexual reproduction vs vegetative reproduction would also provide information on the benefits of sexual dimorphism within populations. For instance, how fruit production increases the dispersal potential of Lgh would help to understand Lgh population dynamics and to propose adapted management practices (Delbart et al., 2013; Meisler, 2009).

To conclude, the study proposes a morphological, reproductive and physiological description of the Lgh sexual reproduction process. However, underlying ecological questions are well included in the article and the ecophysiological results enlighten some questions about the role of sexual reproduction in the invasiveness of Lgh. I advise the reader to pay attention to the reviewers’ comments; the debates were very constructive and, thanks to the great collaboration with the authorship, lead to an interesting paper about Lgh reproduction and with promising perspectives in ecology and invasion ecology.

References

Dandelot S, Robles C, Pech N, Cazaubon A, Verlaque R (2008) Allelopathic potential of two invasive alien Ludwigia spp. Aquatic Botany, 88, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.004

Delbart E, Mahy G, Monty A (2013) Efficacité des méthodes de lutte contre le développement de cinq espèces de plantes invasives amphibies : Crassula helmsii, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Ludwigia grandiflora, Ludwigia peploides et Myriophyllum aquaticum (synthèse bibliographique). BASE, 17, 87–102. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=9586

Gérard J, Brion N, Triest L (2014) Effect of water column phosphorus reduction on competitive outcome and traits of Ludwigia grandiflora and L. peploides, invasive species in Europe. Aquatic Invasions, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.04

Glover R, Drenovsky RE, Futrell CJ, Grewell BJ (2015) Clonal integration in Ludwigia hexapetala under different light regimes. Aquatic Botany, 122, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.01.004

Hieda S, Kaneko Y, Nakagawa M, Noma N (2020) Ludwigia grandiflora (Michx.) Greuter & Burdet subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G. L. Nesom & Kartesz, an Invasive Aquatic Plant in Lake Biwa, the Largest Lake in Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica, 71, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.201911

Meisler J (2009) Controlling Ludwigia hexaplata in Northern California. Wetland Science and Practice, 26, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1672/055.026.0404

Portillo Lemus LO, Harang M, Bozec M, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2022) Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heteromorphic invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala. bioRxiv, 2021.07.15.452457, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457

Portillo Lemus LO, Bozec M, Harang M, Coudreuse J, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2021) Self-incompatibility limits sexual reproduction rather than environmental conditions in an invasive water primrose. Plant-Environment Interactions, 2, 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10042

Reid AJ, Carlson AK, Creed IF, Eliason EJ, Gell PA, Johnson PTJ, Kidd KA, MacCormack TJ, Olden JD, Ormerod SJ, Smol JP, Taylor WW, Tockner K, Vermaire JC, Dudgeon D, Cooke SJ (2019) Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews, 94, 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12480

Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G (2013) A success story: water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 23, 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387

Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiébaut G (2013) Seasonal plasticity of Ludwigia grandiflora under light and water depth gradients: An outdoor mesocosm experiment. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 208, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.004