Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Dec 2021

Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289The promise and limits of DNA based approach to infer diet flexibility in endangered top predatorsRecommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond based on reviews by Francis John Burdon and Babett GüntherThere is growing evidence of worldwide decline of populations of top predators, including marine ones (Heithaus et al, 2008, Mc Cauley et al., 2015), with cascading effects expected at the ecosystem level, due to global change and human activities, including habitat loss or fragmentation, the collapse or the range shifts of their preys. On a global scale, seabirds are among the most threatened group of birds, about one-third of them being considered as threatened or endangered (Votier& Sherley, 2017). The large consequences of the decrease of the populations of preys they feed on (Cury et al, 2011) points diet flexibility as one important element to understand for effective management (McInnes et al, 2017). Nevertheless, morphological inventory of preys requires intrusive protocols, and the differential digestion rate of distinct taxa may lead to a large bias in morphological-based diet assessments. The use of DNA metabarcoding on feces (or diet DNA, dDNA) now allows non-invasive approaches facilitating the recollection of samples and the detection of multiple preys independently of their digestion rates (Deagle et al., 2019). Although no gold standard exists yet to avoid bias associated with metabarcoding (primer bias, gaps in reference databases, inability to differentiate primary from secondary predation…), the use of these recent techniques has already improved the knowledge of the foraging behaviour and diet of many animals (Ando et al., 2020). Both promise and shortcomings of this approach are illustrated in the article “Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)” by Quereteja et al. (2021). In this work, the authors assessed the nature and spatio-temporal flexibility of the foraging behaviour and consequent diet of the endangered petrel Procellaria westlandica from New-Zealand through metabarcoding of faeces samples. The results of this dDNA, non-invasive approach, identify some expected and also unexpected prey items, some of which require further investigation likely due to large gaps in the reference databases. They also reveal the temporal (before and after hatching) and spatial (across colonies only 1.5km apart) flexibility of the foraging behaviour, additionally suggesting a possible influence of fisheries activities in the surroundings of the colonies. This study thus both underlines the power of the non-invasive metabarcoding approach on faeces, and the important results such analysis can deliver for conservation, pointing a potential for diet flexibility that may be essential for the resilience of this iconic yet endangered species. References Ando H, Mukai H, Komura T, Dewi T, Ando M, Isagi Y (2020) Methodological trends and perspectives of animal dietary studies by noninvasive fecal DNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 2, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.117 Cury PM, Boyd IL, Bonhommeau S, Anker-Nilssen T, Crawford RJM, Furness RW, Mills JA, Murphy EJ, Österblom H, Paleczny M, Piatt JF, Roux J-P, Shannon L, Sydeman WJ (2011) Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion—One-Third for the Birds. Science, 334, 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212928 Deagle BE, Thomas AC, McInnes JC, Clarke LJ, Vesterinen EJ, Clare EL, Kartzinel TR, Eveson JP (2019) Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 28, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14734 Heithaus MR, Frid A, Wirsing AJ, Worm B (2008) Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.003 McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347, 1255641. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641 McInnes JC, Jarman SN, Lea M-A, Raymond B, Deagle BE, Phillips RA, Catry P, Stanworth A, Weimerskirch H, Kusch A, Gras M, Cherel Y, Maschette D, Alderman R (2017) DNA Metabarcoding as a Marine Conservation and Management Tool: A Circumpolar Examination of Fishery Discards in the Diet of Threatened Albatrosses. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00277 Querejeta M, Lefort M-C, Bretagnolle V, Boyer S (2021) Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). bioRxiv, 2020.10.30.360289, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289 Votier SC, Sherley RB (2017) Seabirds. Current Biology, 27, R448–R450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.042 | Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica) | Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer | <p style="text-align: justify;">As top predators, seabirds can be indirectly impacted by climate variability and commercial fishing activities through changes in marine communities. However, high mobility and foraging behaviour enables seabirds to... |  | Conservation biology, Food webs, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Sophie Arnaud-Haond | 2020-10-30 20:14:50 | View | |

20 Sep 2018

When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagationMarjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/307322When the dispersal of the many outruns the dispersal of the fewRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

Are biological invasions driven by a few pioneers, running ahead of their conspecifics? Or are these pioneers constantly being caught up by, and folded into, the larger flux of propagules from the established populations behind them? References [1] Levins, R., & Culver, D. (1971). Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68(6), 1246–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246 | When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation | Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100004). Finding general patterns in the expansion of natural populations is a major challenge in ecology and invasion biology... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | Yuval Zelnik | 2018-04-25 10:18:48 | View |

13 May 2024

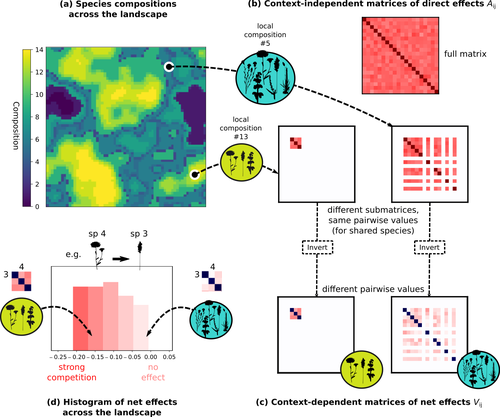

Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in MetacommunitiesMatthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.04.543606Beyond pairwise species interactions: coarser inference of their joined effects is more relevantRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler

Barbier et al. (2024) investigated the dynamics of species abundances depending on their ecological niche (abiotic component) and on (numerous) competitive interactions. In line with previous evidence and expectations (Barbier et al. 2018), the authors show that it is possible to robustly infer the mean and variance of interaction coefficients from species co-distributions, while it is not possible to infer the individual coefficient values. The authors devised a simulation framework representing multispecies dynamics in an heterogeneous environmental context (2D grid landscape). They used a Lotka-Volterra framework involving pairwise interaction coefficients and species-specific carrying capacities. These capacities depend on how well the species niche matches the local environmental conditions, through a Gaussian function of the distance of the species niche centers to the local environmental values. They considered two contrasted scenarios denoted as « Environmental tracking » and « Dispersal limited ». In the latter case, species are initially seeded over the environmental grid and cannot disperse to other cells, while in the former case they can disperse and possibly be more performant in other cells. The direct effects of species on one another are encoded in an interaction matrix A, and the authors further considered net interactions depending on the inverse of the matrix of direct interactions (Zelnik et al., 2024). The net effects are context-dependent, i.e., it involves the environment-dependent biotic capacities, even through the interaction terms can be defined between species as independent from local environment. The results presented here underline that the outcome of many individual competitive interactions can only be understood in terms of macroscopic properties. In essence, the results here echoe the mean field theories that investigate the dynamics of average ecological properties instead of the microscopic components (e.g., McKane et al. 2000). In a philosophical perspective, community ecology has long struggled with analyzing and inferring local determinants of species coexistence from species co-occurrence patterns, so that it was claimed that no universal laws can be derived in the discipline (Lawton 1999). Using different and complementary methods and perspectives, recent research has also shown that species assembly parameter values cannot be unambiguously inferred from species co-occurrences only, even in simple designs where an equilibrium can be reached (Poggiato et al. 2021). Although the roles of high-order competitive interactions and intransivity can lead to species coexistence, the simple view of a single loop of competitive interactions is easily challenged when further interactions and complexity is added (Gallien et al. 2024). But should we put so much emphasis on inferring individual interaction coefficients? In a quest to understand the emerging properties of elementary processes, ecological theory could go forward with a more macroscopic analysis and understanding of species coexistence in many communities. The authors referred several times to an interesting paper from Schaffer (1981), entitled « Ecological abstraction: the consequences of reduced dimensionality in ecological models ». It proposes that estimating individual species competition coefficients is not possible, but that competition can be assessed at the coarser level of organisation, i.e., between ecological guilds. This idea implies that the dimensionality of the competition equations should be greatly reduced to become tractable in practice. Taking together this claim with the results of the present Barbier et al. (2024) paper, it becomes clearer that the nature of competitive interactions can be addressed through « abstracted » quantities, as those of guilds or the moments of the individual competition coefficients (here the average and the standard deviation). Therefore the scope of Barbier et al. (2024) framework goes beyond statistical issues in parameter inference, but question the way we must think and represent the numerous competitive interactions in a simplified and robust way. References Barbier, Matthieu, Jean-François Arnoldi, Guy Bunin, et Michel Loreau. 2018. « Generic assembly patterns in complex ecological communities ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9): 2156‑61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710352115 | Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in Metacommunities | Matthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold | <p>AbstractOne of the more difficult challenges in community ecology is inferring species interactions on the basis of patterns in the spatial distribution of organisms. At its core, the problem is that distributional patterns reflect the ‘realize... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Competition, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2023-10-21 14:14:16 | View | |

03 Apr 2020

A macro-ecological approach to predators' functional responseMatthieu Barbier, Laurie Wojcik, Michel Loreau https://doi.org/10.1101/832220A meta-analysis to infer generic predator functional responseRecommended by Samir Simon Suweis based on reviews by Ludek Berec and gyorgy barabasSpecies interactions are classically derived from the law of mass action: the probability that, for example, a predation event occurs is proportional to the product of the density of the prey and predator species. In order to describe how predator and prey species populations grow, is then necessary to introduce functional response, describing the intake rate of a consumer as a function of food (e.g. prey) density. References [1] Volterra, V. (1928). Variations and Fluctuations of the Number of Individuals in Animal Species living together. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 3(1), 3–51. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/3.1.3 | A macro-ecological approach to predators' functional response | Matthieu Barbier, Laurie Wojcik, Michel Loreau | <p>Predation often deviates from the law of mass action: many micro- and meso-scale experiments have shown that consumption saturates with resource abundance, and decreases due to interference between consumers. But does this observation hold at m... |  | Community ecology, Food webs, Meta-analyses, Theoretical ecology | Samir Simon Suweis | 2019-11-08 15:42:16 | View | |

31 Aug 2023

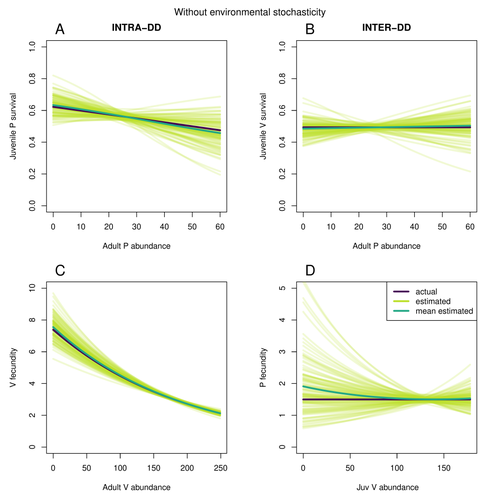

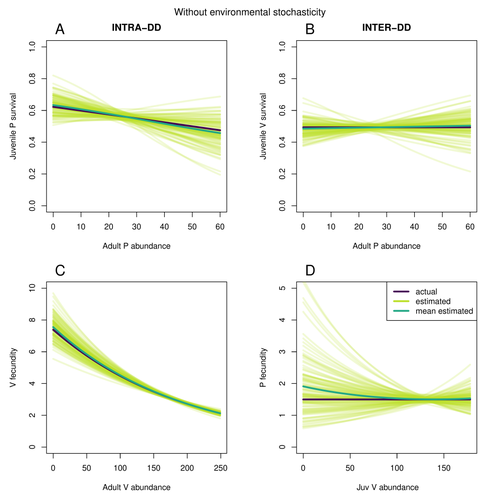

Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey modelsMatthieu Paquet, Frederic Barraquand https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7WAddressing the daunting challenge of estimating species interactions from count dataRecommended by Tim Coulson and David Alonso and David Alonso based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Trophic interactions are at the heart of community ecology. Herbivores consume plants, predators consume herbivores, and pathogens and parasites infect, and sometimes kill, individuals of all species in a food web. Given the ubiquity of trophic interactions, it is no surprise that ecologists and evolutionary biologists strive to accurately characterize them. The outcome of an interaction between individuals of different species depends upon numerous factors such as the age, sex, and even phenotype of the individuals involved and the environment in which they are in. Despite this complexity, biologists often simplify an interaction down to a single number, an interaction coefficient that describes the average outcome of interactions between members of the populations of the species. Models of interacting species tend to be very simple, and interaction coefficients are often estimated from time series of population sizes of interacting species. Although biologists have long known that this approach is often approximate and sometimes unsatisfactory, work on estimating interaction strengths in more complex scenarios, and using ecological data beyond estimates of abundance, is still in its infancy. In their paper, Matthieu Paquet and Frederic Barraquand (2023) develop a demographic model of a predator and its prey. They then simulate demographic datasets that are typical of those collected by ecologists and use integrated population modelling to explore whether they can accurately retrieve the values interaction coefficients included in their model. They show that they can with good precision and accuracy. The work takes an important step in showing that accurate interaction coefficients can be estimated from the types of individual-based data that field biologists routinely collect, and it paves for future work in this area. As if often the case with exciting papers such as this, the work opens up a number of other avenues for future research. What happens as we move from demographic models of two species interacting such as those used by Paquet and Barraquand to more realistic scenarios including multiple species? How robust is the approach to incorrectly specified process or observation models, core components of integrated population modelling that require detailed knowledge of the system under study? Integrated population models have become a powerful and widely used tool in single-species population ecology. It is high time the techniques are extended to community ecology, and this work takes an important step in showing that this should and can be done. I would hope the paper is widely read and cited. References Paquet, M., & Barraquand, F. (2023). Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2RC7W | Assessing species interactions using integrated predator-prey models | Matthieu Paquet, Frederic Barraquand | <p style="text-align: justify;">Inferring the strength of species interactions from demographic data is a challenging task. The Integrated Population Modelling (IPM) approach, bringing together population counts, capture-recapture, and individual-... |  | Community ecology, Demography, Euring Conference, Food webs, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Tim Coulson | Ilhan Özgen-Xian | 2023-01-05 17:02:22 | View |

31 May 2023

Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibiansMatutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425Amphibians under scrutiny - When human-dominated landscape mosaics are not in full compliance with their ecological requirementsRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer

Among vertebrates, amphibians are one of the most diverse groups with more than 7,000 known species. Amphibians occupy various ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, and freshwater habitats. Amphibians are known to be highly sensitive to changes in their environment, particularly to water quality and habitat degradation, so that monitoring abundance of amphibian populations can provide early warning signs of ecosystem disturbances that may also affect other organisms including humans (Bishop et al., 2012). Accordingly, efforts in habitat preservation and sustainable land and water management are necessary to safeguard amphibian populations. In this context, Matutini et al. (2023) compared ecological requirements of amphibian species with the quality of agricultural landscape mosaics. Doing so, they identified critical gaps in existing conservation tools that include protected areas, green infrastructures, and inventoried sites. Matutini et al. (2023) focused on nine amphibian species in the Pays-de-la-Loire region where the landscape has been fashioned over the years by human activities. Three of the chosen amphibian species are living in a dense hedgerow mosaic landscape, while five others are more generalists. Matutini et al. (2023) established multi-species habitat suitability maps, together with their levels of confidence, by combining single species maps with a probabilistic stacking method at 500-m resolution. From these maps, habitats were classified in five categories, from not suitable to highly suitable. Then, the circuit theory was used to map the potential connections between each highly suitable patch at the regional scale. Finally, comparing suitability maps with existing conservation tools, Matutini et al. (2023) were able to assess their coverage and efficiency. Whatever their species status (endangered or not), Matutini et al. (2023) highlighted some discrepancies between the ecological requirements of amphibians in terms of habitat quality and the conservation tools of the landscape mosaic within which they are evolving. More specifically, Matutini et al. (2023) found that protected areas and inventoried sites covered only a small proportion of highly suitable habitats, while green infrastructures covered around 50% of the potential habitat for amphibian species. Such a lack of coverage and efficiency of protected areas brings to light that geographical sites with amphibian conservation challenges are known but not protected. Regarding the landscape fragmentation, Matutini et al. (2023) found that generalist amphibian species have a more homogeneous distribution of suitable habitats at the regional scale. They also identified two bottlenecks between two areas of suitable habitats, a situation that could prove critical to amphibian movements if amphibians were forced to change habitats to global change. In conclusion, Matutini et al. (2023) bring convincing arguments in support of land-use species-conservation planning based on a better consideration of human-dominated landscape mosaics in full compliance with ecological requirements of the species that inhabit the regions concerned. ReferencesBishop, P.J., Angulo, A., Lewis, J.P., Moore, R.D., Rabb, G.B., Moreno, G., 2012. The Amphibian Extinction Crisis - what will it take to put the action into the Amphibian Conservation Action Plan? Sapiens - Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society 5, 1–16. http://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1406 Matutini, F., Baudry, J., Fortin, M.-J., Pain, G., Pithon, J., 2023. Conservation networks do not match ecological requirements of amphibians. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425 | Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibians | Matutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Amphibians are among the most threatened taxa as they are highly sensitive to habitat degradation and fragmentation. They are considered as model species to evaluate habitats quality in agricultural landscapes. I... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-09-20 14:40:03 | View | ||

06 Nov 2023

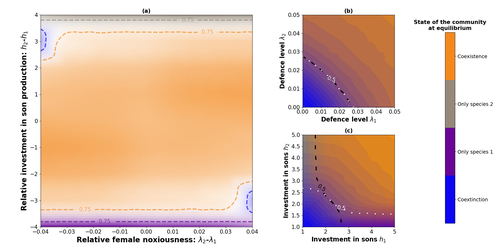

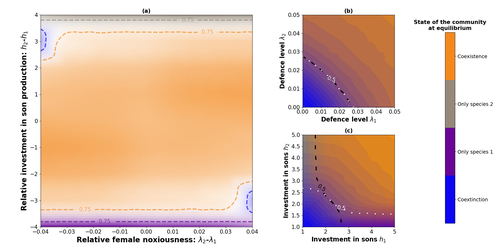

Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approachMaxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153Mullerian and Batesian mimicry can influence population and community dynamicsRecommended by Amanda Franklin based on reviews by Jesus Bellver and 1 anonymous reviewerMimicry between species has long attracted the attention of scientists. Over a century ago, Bates first proposed that palatable species should gain a benefit by resembling unpalatable species (Bates 1862). Not long after, Müller suggested that there could also be a mutual advantage for two unpalatable species to mimic one another to reduce predator error (Müller 1879). These forms of mimicry, Batesian and Müllerian, are now widely studied, providing broad insights into behaviour, ecology and evolution. Numerous taxa, including both invertebrates and vertebrates, show examples of Batesian or Müllerian mimicry. Bees and wasps provide a particularly interesting case due to the differences in defence between females and males of the same species. While both males and females may display warning colours, only females can sting and inject venom to cause pain and allow escape from predators. Therefore, males are palatable mimics and can resemble females of their own species or females of another species (dual sex-limited mimicry). This asymmetry in defence could have impacts on both population structure and community assembly, yet research into mimicry largely focuses on systems without sex differences. Here, Boutin and colleagues (2023) use a differential equations model to explore the effect of mimicry on population structure and community assembly for sex-limited defended species. Specifically, they address three questions, 1) how do female noxiousness and sex-ratio influence the extinction risk of a single species?; 2) what is the effect of mimicry on species co-existence? and 3) how does dual sex-limited mimicry influence species co-existence? Their results reveal contexts in which populations with undefended males can persist, the benefit of Müllerian mimicry for species coexistence and that dual sex-limited mimicry can have a destabilising impact on species coexistence. The results not only contribute to our understanding of how mimicry is maintained in natural systems but also demonstrate how changes in relative abundance or population structure of one species could impact another species. Further insight into the population and community dynamics of insects is particularly important given the current population declines (Goulson 2019; Seibold et al 2019). References Bates, H. W. 1862. Contributions to the insect fauna of the Amazon Valley, Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23:495- 566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x Boutin, M., Costa, M., Fontaine, C., Perrard, A., Llaurens, V. 2022 Influence of sex-limited mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153 Goulson, D. 2019. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Curr. Biol. 29: R967-R971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.069 Müller, F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia; a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Roy. Entom. Roc. 1879:20-29. Seibold, S., Gossner, M. M., Simons, N. K., Blüthgen, N., Müller, J., Ambarlı, D., ... & Weisser, W. W. 2019. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature, 574: 671-674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1684-3 | Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach | Maxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens | <p style="text-align: justify;">Positive ecological interactions, such as mutualism, can play a role in community structure and species co-existence. A well-documented case of mutualistic interaction is Mullerian mimicry, the convergence of colour... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism | Amanda Franklin | 2022-10-25 19:11:55 | View | |

26 May 2023

Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibilityMcCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59KDo reversal learning methods measure behavioral flexibility?Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh

Assessing the reliability of the methods we use in actually measuring the intended trait should be one of our first priorities when designing a study – especially when the trait in question is not directly observable and is measured through a proxy. This is the case for cognitive traits, which are often quantified through measures of behavioral performance. Behavioral flexibility is of particular interest in the context of great environmental changes that a lot of populations have to experiment. This type of behavioral performance is often measured through reversal learning experiments (Bond 2007). In these experiments, individuals first learn a preference, for example for an object of a certain type of form or color, associated with a reward such as food. The characteristics of the rewarded object then change, and the individuals hence have to learn these new characteristics (to get the reward). The time needed by the individual to make this change in preference has been considered a measure of behavioral flexibility. Although reversal learning experiments have been widely used, their construct validity to assess behavioral flexibility has not been thoroughly tested. This was the aim of McCune and collaborators' (2023) study, through the test of the repeatability of individual performance within and across contexts of reversal learning, in the great-tailed grackle. This manuscript presents a post-study of the preregistered study* (Logan et al. 2019) that was peer-reviewed and received an In Principle Recommendation for PCI Ecology (Coulon 2019; the initial preregistration was split into 3 post-studies).

The first hypothesis was tested by measuring the repeatability of the time needed by individuals to switch color preference in a color reversal learning task (colored tubes), over serial sessions of this task. The second one was tested by measuring the time needed by individuals to switch solutions, within 3 different contexts: (1) colored tubes, (2) plastic and (3) wooden multi-access boxes involving several ways to access food. Despite limited sample sizes, the results of these experiments suggest that there is both temporal and contextual repeatability of behavioral flexibility performance of great-tailed grackles, as measured by reversal learning experiments. Those results are a first indication of the construct validity of reversal learning experiments to assess behavioral flexibility. As highlighted by McCune and collaborators, it is now necessary to assess the discriminant validity of these experiments, i.e. checking that a different performance is obtained with tasks (experiments) that are supposed to measure different cognitive abilities. Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Logan, CJ, Lukas D, Bergeron L, Folsom M, & McCune, K. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In Principle Acceptance by PCI Ecology of the Version on 6 Aug 2019. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ (2023) Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59K | Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility | McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Research into animal cognitive abilities is increasing quickly and often uses methods where behavioral performance on a task is assumed to represent variation in the underlying cognitive trait. However, because thes... | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-08-15 20:56:42 | View | ||

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

29 Aug 2023

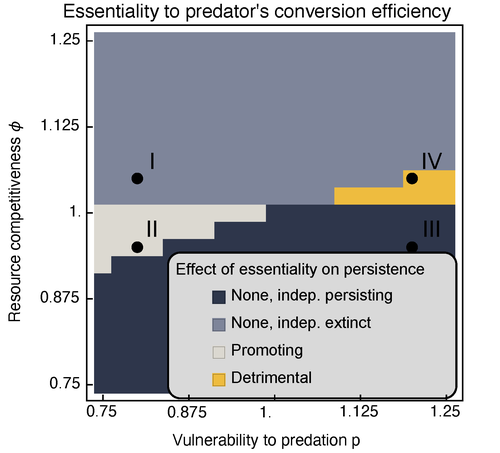

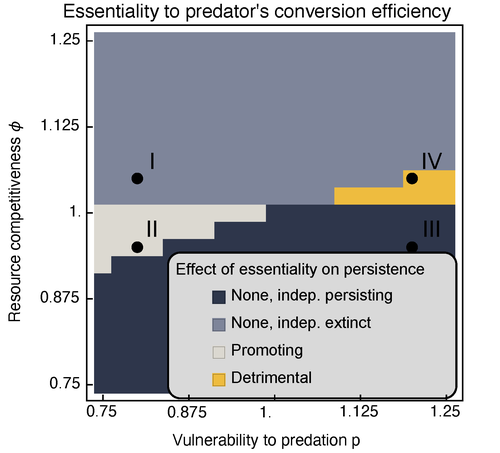

Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food websMichael Raatz https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839High-order interactions in food webs may strongly impact persistence of speciesRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer

Michael Raatz (2023) provides here a relevant exploration of higher-order interactions, i.e. interactions involving more than two related species (Terry et al. 2019), in the case of food web and competition interactions. More precisely, he shows by modeling that essential resources may significantly mediate focal species' persistence. Simultaneously, the provision of essential resources may strongly affect the resulting community structure, by driving to extinction first the predator and then, depending on the higher-order interaction, potentially also the associated competitor. Today, all ecologists should be aware of the potential effects of high-order interactions on species' (and likely on ecosystem's) fate (Golubski et al. 2016, Grilli et al. 2017). Yet, we should soon be prepared to include any high-order interaction into any interaction network (i.e. not only between species, but also between species and abiotic components, and between biotic, anthropogenic and abiotic components too). For this purpose, we will need innovative approaches such as hypergraphs (Golubski et al. 2016) and discrete-event models (Gaucherel and Pommereau 2019, Thomas et al. 2022) able to manage highly complex interactions, with numerous interacting components and variables. Such a rigorous study is a necessary and preliminary step in taking into account such a higher complexity. References Gaucherel, C. and F. Pommereau. 2019. Using discrete systems to exhaustively characterize the dynamics of an integrated ecosystem. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 00:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13242 Golubski, A. J., E. E. Westlund, J. Vandermeer, and M. Pascual. 2016. Ecological Networks over the Edge: Hypergraph Trait-Mediated Indirect Interaction (TMII) Structure trends in Ecology & Evolution 31:344-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.006 Grilli, J., G. Barabas, M. J. Michalska-Smith, and S. Allesina. 2017. Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature 548:210-213. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23273 Raatz, M. 2023. Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839 Terry, J. C. D., R. J. Morris, and M. B. Bonsall. 2019. Interaction modifications lead to greater robustness than pairwise non-trophic effects in food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 88:1732-1742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13057 Thomas, C., M. Cosme, C. Gaucherel, and F. Pommereau. 2022. Model-checking ecological state-transition graphs. PLoS Computational Biology 18:e1009657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009657 | Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs | Michael Raatz | <p style="text-align: justify;">Pairwise interactions in food webs, including those between predator and prey are often modulated by a third species. Such higher-order interactions are important structural components of natural food webs that can ... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Competition, Ecological stoichiometry, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | 2023-02-23 17:48:26 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle