Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Apr 2024

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

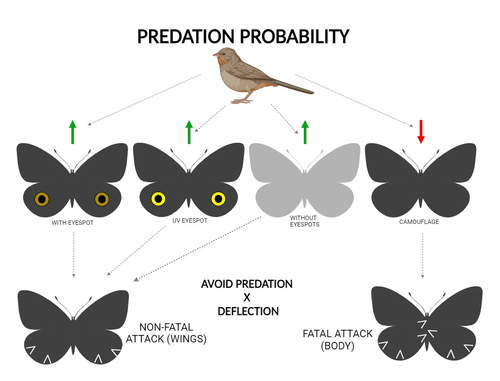

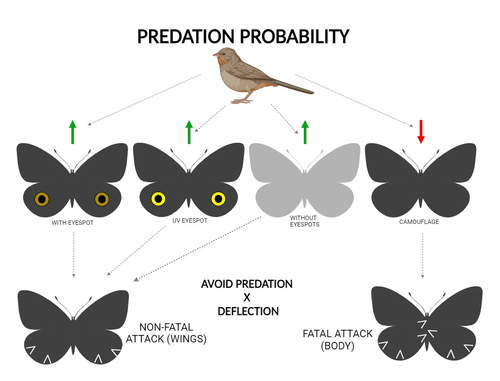

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

01 Mar 2023

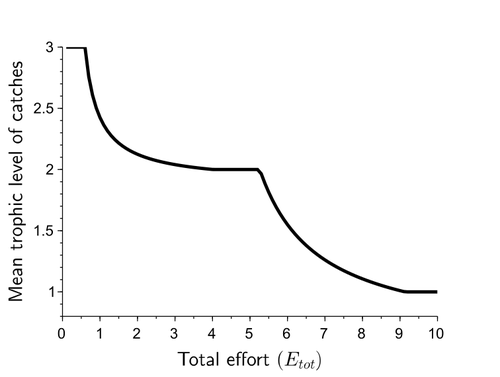

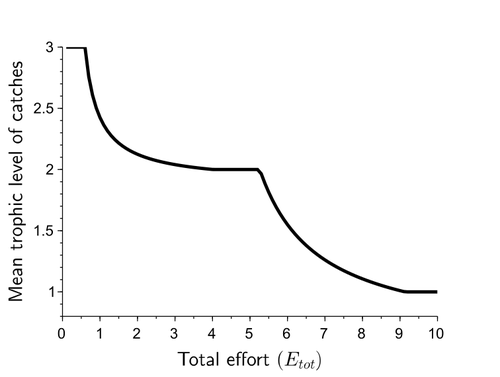

Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systemsEric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/290460Adaptive harvesting, “fishing down the food web”, and regime shiftsRecommended by Amanda Lynn Caskenette based on reviews by Pierre-Yves HERNVANN and 1 anonymous reviewerThe mean trophic level of catches in world fisheries has generally declined over the 20th century, a phenomenon called "fishing down the food web" (Pauly et al. 1998). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this decline including the collapse of, or decline in, higher trophic level stocks leading to the inclusion of lower trophic level stocks in the fishery. Fishing down the food web may lead to a reduction in the resilience, i.e., the capacity to rebound from change, of the fished community, which is concerning given the necessity of resilience in the face of climate change. The practice of adaptive harvesting, which involves fishing stocks based on their availability, can also result in a reduction in the average trophic level of a fishery (Branch et al. 2010). Adaptive harvesting, similar to adaptive foraging, can affect the resilience of fisheries. Generally, adaptive foraging acts as a stabilizing force in communities (Valdovinos et al. 2010), however it is not clear how including harvesters as the adaptive foragers will affect the resilience of the system. Tromeur and Loeuille (2023) analyze the effects of adaptively harvesting a trophic community. Using a system of ordinary differential equations representing a predator-prey model where both species are harvested, the researchers mathematically analyze the impact of increasing fishing effort and adaptive harvesting on the mean trophic level and resilience of the fished community. This is achieved by computing the equilibrium densities and equilibrium allocation of harvest effort. In addition, the researchers numerically evaluate adaptive harvesting in a tri-trophic system (predator, prey, and resource). The study focuses on the effect of adaptively distributing harvest across trophic levels on the mean trophic level of catches, the propensity for regime shifts to occur, the ability to return to equilibrium after a disturbance, and the speed of this return. The results indicate that adaptive harvesting leads to a decline in the mean trophic level of catches, resulting in “fishing down the food web”. Furthermore, the study shows that adaptive harvesting may harm the overall resilience of the system. Similar results were observed numerically in a tri-trophic community. While adaptive foraging is generally a stabilizing force on communities, the researchers found that adaptive harvesting can destabilize the harvested community. One of the key differences between adaptive foraging models and the model presented here, is that the harvesters do not exhibit population dynamics. This lack of a numerical response by the harvesters to decreasing population sizes of their stocks leads to regime shifts. The realism of a fishery that does not respond numerically to declining stock is debatable, however it is very likely that there will a least be significant delays due to social and economic barriers to leaving the fishery, that will lead to similar results. This study is not unique in demonstrating the ability of adaptive harvesting to result in “fishing down the food web”. As pointed out by the researchers, the same results have been shown with several different model formulations (e.g., age and size structured models). Similarly, this study is not unique to showing that increasing adaptation speeds decreases the resilience of non-linear predator-prey systems by inducing oscillatory behaviours. Much of this can be explained by the destabilising effect of increasing interaction strengths on food webs (McCann et al. 1998). By employing a straightforward model, the researchers were able to demonstrate that adaptive harvesting, a common strategy employed by fishermen, can result in a decline in the average trophic level of catches, regime shifts, and reduced resilience in the fished community. While previous studies have observed some of these effects, the fact that the current study was able to capture them all with a simple model is notable. This modeling approach can offer insight into the role of human behavior on the complex dynamics observed in fisheries worldwide. References Branch, T. A., R. Watson, E. A. Fulton, S. Jennings, C. R. McGilliard, G. T. Pablico, D. Ricard, et al. 2010. The trophic fingerprint of marine fisheries. Nature 468:431–435. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09528 Tromeur, E., and N. Loeuille. 2023. Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems. bioRxiv 290460, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/290460 McCann, K., A. Hastings, and G.R. Huxel. 1998. Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature 395: 794-798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427 Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Froese, and F. Torres Jr. 1998. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–86. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860 Valdovinos, F.S., R. Ramos-Jiliberto, L. Garay-Naravez, P. Urbani, and J.A. Dunne. 2010. Consequences of adaptive behaviour for the structure and dynamics of food webs. Ecology Letters 13: 1546-1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01535.x | Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems | Eric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Many world fisheries display a declining mean trophic level of catches. This "fishing down the food web" is often attributed to reduced densities of high-trophic-level species. We show here that the fishing down pattern can actually emerge from... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Amanda Lynn Caskenette | 2022-05-03 21:09:35 | View | |

27 Jan 2023

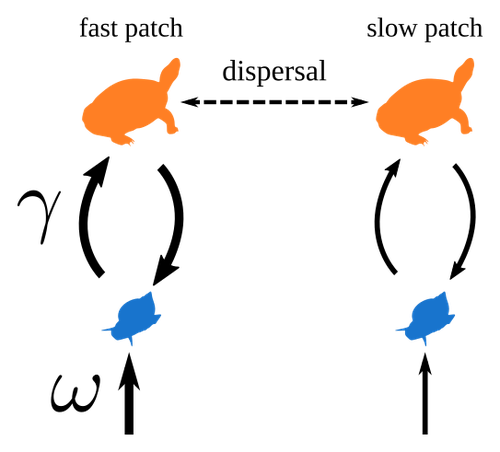

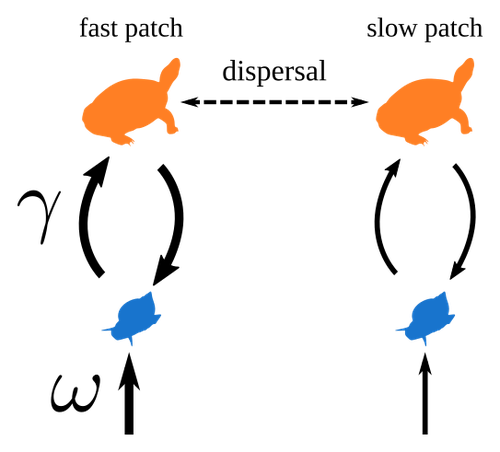

Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunitiesPierre Quévreux, Bart Haegeman and Michel Loreau https://hal.science/hal-03829838How does spatial heterogeneity affect stability of trophic metacommunities?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko, Ludek Berec and Diogo Provete based on reviews by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko, Ludek Berec and Diogo Provete

The temporal or spatial variability in species population sizes and interaction strength of animal and plant communities has a strong impact on aggregate community properties (for instance biomass), community composition, and species richness (Kokkoris et al. 2002). Early work on spatial and temporal variability strongly indicated that asynchronous population and environmental fluctuations tend to stabilise community structures and diversity (e.g. Holt 1984, Tilman and Pacala 1993, McCann et al. 1998, Amarasekare and Nisbet 2001). Similarly, trophic networks might be stabilised by spatial heterogeneity (Hastings 1977) and an asymmetry of energy flows along food chains (Rooney et al. 2006). The interplay between temporal, spatial, and trophic heterogeneity within the meta-community concept has got much less interest. In the recent preprint in PCI Ecology, Quévreux et al. (2023) report that Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. These authors rightly notice that the interplay between trophic and spatial heterogeneity might induce contrasting effects depending on the internal dynamics of the system. Their contribution builds on prior work (Quévreux et al. 2021a, b) on perturbed trophic cascades. I found this paper particularly interesting because it is in the, now century-old, tradition to show that ecological things are not so easy. Since the 1930th, when Nicholson and Baily and others demonstrated that simple deterministic population models might generate stability and (pseudo-)chaos ecologists have realised that systems triggered by two or more independent processes might be intrinsically unpredictable and generate different outputs depending on the initial parameter settings. This resembles the three-body problem in physics. The present contribution of Quévreux et al. (2023) extends this knowledge to an example of a spatially explicit trophic model. Their main take-home message is that asymmetric energy flows in predator–prey relationships might have contrasting effects on the stability of metacommunities receiving localised perturbations. Stability is context dependent. Of course, the work is merely a theoretical exercise using a simplistic trophic model. It demands verification with field data. Nevertheless, we might expect even stronger unpredictability in more realistic multitrophic situations. Therefore, it should be seen as a proof of concept. Remember that increasing trophic connectance tends to destabilise food webs (May 1972). In this respect, I found the final outlook to bioconservation ambitious but substantiated. Biodiversity management needs a holistic approach focusing on all aspects of ecological functioning. I would add the need to see stability and biodiversity within an evolutionary perspective. References Amarasekare P, Nisbet RM (2001) Spatial Heterogeneity, Source‐Sink Dynamics, and the Local Coexistence of Competing Species. The American Naturalist, 158, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1086/323586 Hastings A (1977) Spatial heterogeneity and the stability of predator-prey systems. Theoretical Population Biology, 12, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(77)90034-X Holt RD (1984) Spatial Heterogeneity, Indirect Interactions, and the Coexistence of Prey Species. The American Naturalist, 124, 377–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/284280 Kokkoris GD, Jansen VAA, Loreau M, Troumbis AY (2002) Variability in interaction strength and implications for biodiversity. Journal of Animal Ecology, 71, 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00604.x May RM (1972) Will a Large Complex System be Stable? Nature, 238, 413–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/238413a0 McCann K, Hastings A, Huxel GR (1998) Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature, 395, 794–798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427 Quévreux P, Barbier M, Loreau M (2021) Synchrony and Perturbation Transmission in Trophic Metacommunities. The American Naturalist, 197, E188–E203. https://doi.org/10.1086/714131 Quévreux P, Pigeault R, Loreau M (2021) Predator avoidance and foraging for food shape synchrony and response to perturbations in trophic metacommunities. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 528, 110836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110836 Quévreux P, Haegeman B, Loreau M (2023) Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. hal-03829838, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.science/hal-03829838 Rooney N, McCann K, Gellner G, Moore JC (2006) Structural asymmetry and the stability of diverse food webs. Nature, 442, 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04887 Tilman D, Pacala S (1993) The maintenance of species richness in plant communities. In: Ricklefs, R.E., Schluter, D. (eds) Species Diversity in Ecological Communities: Historical and Geographical Perspectives. University of Chicago Press, pp. 13–25. | Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities | Pierre Quévreux, Bart Haegeman and Michel Loreau | <p> Spatial heterogeneity is a fundamental feature of ecosystems, and ecologists have identified it as a factor promoting the stability of population dynamics. In particular, differences in interaction strengths and resource supply between pa... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Food webs, Interaction networks, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Werner Ulrich | 2022-10-26 13:38:34 | View | |

06 Mar 2020

Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food websPierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault https://doi.org/10.1101/276592New insights into the role of nutrient cycling in food web dynamicsRecommended by Samraat Pawar based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the factors that govern the relationship between structure, stability and functioning of food webs has been a central problem in ecology for many decades. Historically, apart from microbial and soil food webs, the role of nutrient cycling has largely been ignored in theoretical and empirical food web studies. A prime example of this is the widespread use of Lotka-Volterra type models in theoretical studies; these models per se are not designed to capture the effect of nutrients being released back into the system by interacting populations. Thus overall, we still lack a general understanding of how nutrient cycling affects food web dynamics. References [1] Quévreux, P., Barot, S. and E. Thébault (2020) Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs. bioRxiv, 276592, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/276592 | Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs | Pierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault | <p>Nutrient cycling is fundamental to ecosystem functioning. Despite recent major advances in the understanding of complex food web dynamics, food web models have so far generally ignored nutrient cycling. However, nutrient cycling is expected to ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Samraat Pawar | 2018-11-03 21:47:37 | View | ||

10 Oct 2018

Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence dataSamuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea https://doi.org/10.1101/256586Combining epidemiological models with statistical inference can detect parasite interactionsRecommended by Dustin Brisson based on reviews by Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne and 1 anonymous reviewerThere are several important topics in the study of infectious diseases that have not been well explored due to technical difficulties. One such topic is pursued by Alizon et al. in “Modelling coinfections to detect within-host interactions from genotype combination prevalences” [1]. Both theory and several important examples have demonstrated that interactions among co-infecting strains can have outsized impacts on disease outcomes, transmission dynamics, and epidemiology. Unfortunately, empirical data on pathogen interactions and their outcomes is often correlational making results difficult to decipher. References [1] Alizon, S., Murall, C.L., Saulnier, E., & Sofonea, M.T. (2018). Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data. bioRxiv, 256586, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/256586 | Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data | Samuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea | <p>Parasite genetic diversity can provide information on disease transmission dynamics but most methods ignore the exact combinations of genotypes in infections. We introduce and validate a new method that combines explicit epidemiological modelli... |  | Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Statistical ecology | Dustin Brisson | Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne | 2018-02-01 09:23:26 | View |

13 Jul 2023

Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predatorsLoïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552Indirect effects of parasitism include increased profitability of prey to optimal foragersRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Thierry DE MEEUS and Eglantine Mathieu-BégnéEven though all living organisms are, at the same time, involved in host-parasite interactions and embedded in complex food webs, the indirect effects of parasitism are only beginning to be unveiled. Prosnier et al. investigated the direct and indirect effects of parasitism making use of a very interesting biological system comprising the freshwater zooplankton Daphnia magna and its highly specific parasite, the iridovirus DIV-1 (Daphnia-iridescent virus 1). Daphnia are typically semitransparent, but once infected develop a white phenotype with a characteristic iridescent shine due to the enlargement of white fat cells. In a combination of infection trials and comparison of white and non-white phenotypes collected in natural ponds, the authors demonstrated increased mortality and reduced lifetime fitness in infected Daphnia. Furthermore, white phenotypes had lower mobility, increased reflectance, larger body sizes and higher protein content than non-white phenotypes. As a consequence, total energy content was effectively doubled in white Daphnia when compared to non-white broodless Daphnia. Next the authors conducted foraging trials with Daphnia predators Notonecta (the backswimmer) and Phoxinus (the European minnow). Focusing on Notonecta, unchanged search time and increased handling time were more than compensated by the increased energy content of white Daphnia. White Daphnia were 24% more profitable and consistently preferred by Notonecta, as the optimal foraging theory would predict. The authors argue that menu decisions of optimal foragers in the field might be different, however, as the prevalence – and therefore availability - of white phenotypes in natural populations is very low. The study therefore contributes to our understanding of the trophic context of parasitism. One shortcoming of the study is that the authors rely exclusively on phenotypic signs for determining infection. On their side, DIV-1 is currently known to be highly specific to Daphnia, their study site is well within DIV-1 distributional range, and the symptoms of infection are very conspicuous. Furthermore, the infection trial – in which non-white Daphnia were exposed to white Daphnia homogenates - effectively caused several lethal and sublethal effects associated with DIV-1 infection, including iridescence. However, the infection trial also demonstrated that part of the exposed individuals developed intermediate traits while still keeping the non-white, non-iridescent phenotype. Thus, there may be more subtleties to the association of DIV-1 infection of Daphnia with ecological and evolutionary consequences, such as costs to resistance or covert infection, that the authors acknowledge, and that would be benefitted by coupling experimental and observational studies with the determination of actual infection and viral loads. References Prosnier L., N. Loeuille, F.D. Hulot, D. Renault, C. Piscart, B. Bicocchi, M, Deparis, M. Lam, & V. Médoc. (2023). Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552 | Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators | Loïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc | <p>Parasites are omnipresent, and their eco-evolutionary significance has aroused much interest from scientists. Parasites may affect their hosts in many ways by altering host density, vulnerability to predation, and energy content, thus modifying... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Epidemiology, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Life history, Parasitology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2022-05-20 10:15:41 | View | |

30 Mar 2020

Environmental variables determining the distribution of an avian parasite: the case of the Philornis torquans complex (Diptera: Muscidae) in South AmericaPablo F. Cuervo, Alejandro Percara, Lucas Monje, Pablo M. Beldomenico, Martín A. Quiroga https://doi.org/10.1101/839589Catching the fly in dystopian timesRecommended by Rodrigo Medel based on reviews by 4 anonymous reviewersHost-parasite interactions are ubiquitous on Earth. They are present in almost every conceivable ecosystem and often result from a long history of antagonist coevolution [1,2]. Recent studies on climate change have revealed, however, that modification of abiotic variables are often accompanied by shifts in the distributional range of parasites to habitats far beyond their original geographical distribution, creating new interactions in novel habitats with unpredictable consequences for host community structure and organization [3,4]. This situation may be especially critical for endangered host species having small population abundance and restricted distribution range. The infestation of bird species with larvae of the muscid fly genus Philornis is a case in point. At least 250 bird species inhabiting mostly Central and South America are infected by Philornis flies [5,6]. Fly larval development occurs in bird faeces, nesting material, or inside nestlings, affecting the development and nestling survival. References [1] Thompson JN (1994) The Coevolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press. | Environmental variables determining the distribution of an avian parasite: the case of the Philornis torquans complex (Diptera: Muscidae) in South America | Pablo F. Cuervo, Alejandro Percara, Lucas Monje, Pablo M. Beldomenico, Martín A. Quiroga | <p>*Philornis* flies are the major cause of myasis in altricial nestlings of neotropical birds. Its impact ranges from subtle to lethal, being of major concern in endangered bird species with geographically-restricted, fragmented and small-sized p... |  | Biogeography, Macroecology, Parasitology, Species distributions | Rodrigo Medel | 2019-11-26 21:31:33 | View | |

11 May 2020

Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa)Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier https://doi.org/10.1101/557066Urban past predicts contemporary genetic structure in city ratsRecommended by Michelle DiLeo based on reviews by Torsti Schulz, ? and 1 anonymous reviewerUrban areas are expanding worldwide, and have become a dominant part of the landscape for many species. Urbanization can fragment pre-existing populations of vulnerable species leading to population declines and the loss of connectivity. On the other hand, expansion of urban areas can also facilitate the spread of human commensals including pests. Knowledge of the features of cityscapes that facilitate gene flow and maintain diversity of pests is thus key to their management and eradication. References [1] Rivkin, L. R., Santangelo, J. S., Alberti, M. et al. (2019). A roadmap for urban evolutionary ecology. Evolutionary Applications, 12(3), 384-398. doi: 10.1111/eva.12734 | Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa) | Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier | <p>Population genetic approaches may be used to investigate dispersal patterns of species living in highly urbanized environment in order to improve management strategies for biodiversity conservation or pest control. However, in such environment,... |  | Biological invasions, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology | Michelle DiLeo | 2019-02-22 08:36:13 | View | |

15 Feb 2024

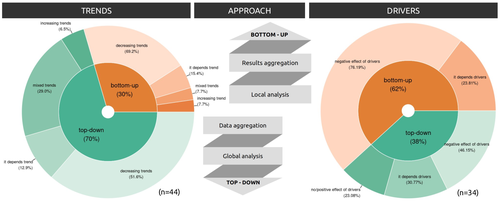

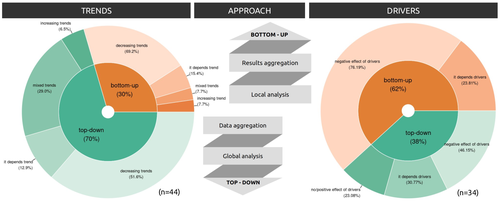

Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trendsMaelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3HUnraveling the Complexity of Global Biodiversity Dynamics: Insights and ImperativesRecommended by Paulo Borges based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer

Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across terrestrial and marine ecosystems, driven by various processes that degrade habitats and threaten species with extinction. Despite the urgency of this issue, empirical studies present a mixed picture, with some indicating declining trends while others show more complex patterns. In a recent effort to better understand global biodiversity dynamics, Boennec et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive literature review examining temporal trends in biodiversity. Their analysis reveals that reviews and meta-analyses, coupled with the use of global indicators, tend to report declining trends more frequently. Additionally, the study underscores a critical gap in research: the scarcity of investigations into the combined impact of multiple pressures on biodiversity at a global scale. This lack of understanding complicates efforts to identify the root causes of biodiversity changes and develop effective conservation strategies. This study serves as a crucial reminder of the pressing need for long-term biodiversity monitoring and large-scale conservation studies. By filling these gaps in knowledge, researchers can provide policymakers and conservation practitioners with the insights necessary to mitigate biodiversity loss and safeguard ecosystems for future generations. References Boennec, M., Dakos, V. & Devictor, V. (2023). Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trend. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3H

| Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trends | Maelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor | <p>Populations and ecological communities are changing worldwide, and empirical studies exhibit a mixture of either declining or mixed trends. Confusion in global biodiversity trends thus remains while assessing such changes is of major social, po... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Meta-analyses | Paulo Borges | 2023-09-20 11:10:25 | View | |

03 Apr 2020

A macro-ecological approach to predators' functional responseMatthieu Barbier, Laurie Wojcik, Michel Loreau https://doi.org/10.1101/832220A meta-analysis to infer generic predator functional responseRecommended by Samir Simon Suweis based on reviews by Ludek Berec and gyorgy barabasSpecies interactions are classically derived from the law of mass action: the probability that, for example, a predation event occurs is proportional to the product of the density of the prey and predator species. In order to describe how predator and prey species populations grow, is then necessary to introduce functional response, describing the intake rate of a consumer as a function of food (e.g. prey) density. References [1] Volterra, V. (1928). Variations and Fluctuations of the Number of Individuals in Animal Species living together. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 3(1), 3–51. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/3.1.3 | A macro-ecological approach to predators' functional response | Matthieu Barbier, Laurie Wojcik, Michel Loreau | <p>Predation often deviates from the law of mass action: many micro- and meso-scale experiments have shown that consumption saturates with resource abundance, and decreases due to interference between consumers. But does this observation hold at m... |  | Community ecology, Food webs, Meta-analyses, Theoretical ecology | Samir Simon Suweis | 2019-11-08 15:42:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle