Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Sep 2020

The dynamics of spawning acts by a semelparous fish and its associated energetic costsCédric Tentelier, Colin Bouchard, Anaïs Bernardin, Amandine Tauzin, Jean-Christophe Aymes, Frédéric Lange, Charlotte Recapet, Jacques Rives https://doi.org/10.1101/436295Extreme weight loss: when accelerometer could reveal reproductive investment in a semelparous fish speciesRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison, Loïc Teulier and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Aidan Jonathan Mark Hewison, Loïc Teulier and 1 anonymous reviewer

Continuous observation of animal behaviour could be quite a challenge in the field, and the situation becomes even more complicated with aquatic species mostly active at night. In such cases, biologging techniques are real game changers in ecology, behavioural ecology or eco-physiology. An accelerating number of methodological applications of these tools in natural condition are thus published each year [1]. Biologging is not limited to movement ecology. For instance, fine grain information about energy expenditure can be inferred from body acceleration [2], and accelerometers has already proven useful in monitoring reproductive costs in some fish species [3,4]. The first part of the study by Tentelier et al. [5] is in line with this growing literature. It describes measurements of energy expenditure during reproduction in a fish species, Allis shad (Alosa Alosa), based on tail beat frequency and occurrence of spawning acts. The study has been convincingly conducted, and the results are important for fish biologists. But this is not the whole story: the authors added to this otherwise classical study a very original and insightful analysis which deserves closer interest. References [1] Börger L, Bijleveld AI, Fayet AL, Machovsky‐Capuska GE, Patrick SC, Street GM and Vander Wal E. (2020) Biologging special feature. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 6–15. 10.1111/1365-2656.13163 | The dynamics of spawning acts by a semelparous fish and its associated energetic costs | Cédric Tentelier, Colin Bouchard, Anaïs Bernardin, Amandine Tauzin, Jean-Christophe Aymes, Frédéric Lange, Charlotte Recapet, Jacques Rives | <p>1. During the reproductive season, animals have to manage both their energetic budget and gamete stock. In particular, for semelparous capital breeders with determinate fecundity and no parental care other than gametic investment, the depletion... | Behaviour & Ethology, Freshwater ecology, Life history | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2020-06-04 15:18:56 | View | ||

29 Sep 2023

MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modellingOndřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.05.531080A deep learning model to unlock secrets of animal movement and behaviourRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

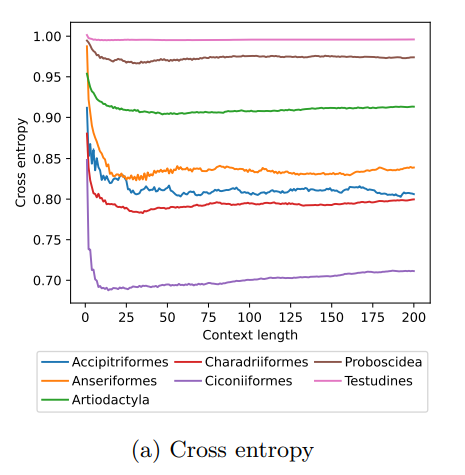

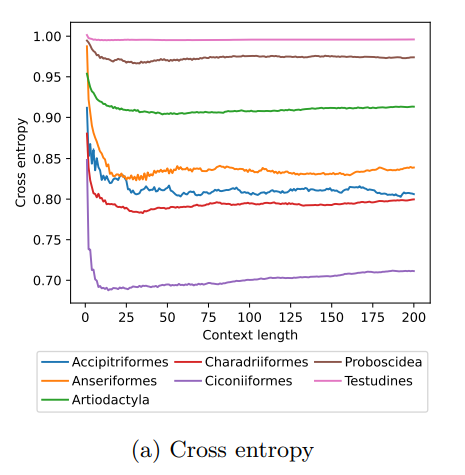

The study of animal movement is essential for understanding their behaviour and how ecological or global changes impact their routines [1]. Recent technological advancements have improved the collection of movement data [2], but limited statistical tools have hindered the analysis of such data [3–5]. Animal movement is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by internal knowledge and memory, which are challenging to observe directly [6,7]. Routine movement behaviours and the incorporation of memory into models remain understudied. Researchers have developed ‘MoveFormer’ [8], a deep learning-based model that predicts future movements based on past context, addressing these challenges and offering insights into the importance of different context lengths and information types. The model has been applied to a dataset of over 1,550 trajectories from various species, and the authors have made the MoveFormer source code available for further research. Inspired by the step-selection framework and efforts to quantify uncertainty in movement predictions, MoveFormer leverages deep learning, specifically the Transformer architecture, to encode trajectories and understand how past movements influence current and future ones – a critical question in movement ecology. The results indicate that integrating information from a few days to two or three weeks before the movement enhances predictions. The model also accounts for environmental predictors and offers insights into the factors influencing animal movements. Its potential impact extends to conservation, comparative analyses, and the generalisation of uncertainty-handling methods beyond ecology, with open-source code fostering collaboration and innovation in various scientific domains. Indeed, this method could be applied to analyse other kinds of movements, such as arm movements during tool use [9], pen movements, or eye movements during drawing [10], to better understand anticipation in actions and their intentionality. References 1. Méndez, V.; Campos, D.; Bartumeus, F. Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous Diffusion, Front Propagation and Random Searches; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-39009-8. | MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modelling | Ondřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus | <p style="text-align: justify;">The movement of animals is a central component of their behavioural strategies. Statistical tools for movement data analysis, however, have long been limited, and in particular, unable to account for past movement i... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Habitat selection | Cédric Sueur | 2023-03-22 16:32:14 | View | |

29 Nov 2019

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalAugust Sevchik, Corina Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Aaron Blackwell, Carolyn Rowney, Dieter Lukas http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gdispersal.htmlInvestigate fine scale sex dispersal with spatial and genetic analysesRecommended by Sophie Beltran-Bech based on reviews by Sylvine Durand and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Sylvine Durand and 1 anonymous reviewer

The preregistration "Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal" [1] presents the analysis plan that will be used to genetically and spatially investigate sex-biased dispersal in great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). References [1] Sevchik A., Logan C. J., Folsom M., Bergeron L., Blackwell A., Rowney C., and Lukas D. (2019). Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gdispersal.html | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | August Sevchik, Corina Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Aaron Blackwell, Carolyn Rowney, Dieter Lukas | In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain close to the place they were hatched for their entire lives (Greenwood and Harvey (1982)). Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have f... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Life history, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Sophie Beltran-Bech | 2019-07-24 12:47:07 | View | |

02 Aug 2022

The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8naWhen do dominant females have higher breeding success than subordinates? A meta-analysis across social mammals.Recommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this meta-analysis, Shivani et al. [1] investigate 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals and 2) whether this relationship varies according to a) life history traits (e.g., stronger for species with large litter size), b) ecological conditions (e.g., stronger when resources are limited) and c) the social environment (e.g., stronger for cooperative breeders than for plural breeders). Generally, the results are consistent with their predictions, except there was no clear support for this relationship to be conditional on the ecological conditions. considered As I have previously recommended the preregistration of this study [2,3], I do not have much to add here, as such recommendation should not depend on the outcome of the study. What I would like to recommend is the whole scientific process performed by the authors, from preregistration sent for peer review, to preprint submission and post-study peer review. It is particularly recommendable to notice that this project was a Masters student project, which shows that it is possible and worthy to preregister studies, even for such rather short-term projects. I strongly congratulate the authors for choosing this process even for an early career short-term project. I think it should be made possible for short-term students to conduct a preregistration study as a research project, without having to present post-study results. I hope this study can encourage a shift in the way we sometimes evaluate students’ projects. I also recommend the readers to look into the whole pre- and post- study reviewing history of this manuscript and the associated preregistration, as it provides a better understanding of the process and a good example of the associated challenges and benefits [4]. It was a really enriching experience and I encourage others to submit and review preregistrations and registered reports!

References [1] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2022). The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals. EcoEvoRxiv, rc8na, ver. 10 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8na [2] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2020). Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version 1.2 on 07 July 2020. https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.html [3] Paquet, M. (2020) Why are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammals. Peer Community in Ecology, 100056. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100056 [4] Parker, T., Fraser, H., & Nakagawa, S. (2019). Making conservation science more reliable with preregistration and registered reports. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 747-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13342 | The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses | Matthieu Paquet | 2021-10-13 18:26:42 | View | |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

26 Mar 2019

Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context?Corina Logan, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Kelsey McCune http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.htmlCan context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changesRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Andrea Griffin based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Andrea Griffin

Behavioral flexibility is a key for species adaptation to new environments. Predicting species responses to new contexts hence requires knowledge on the amount to and conditions in which behavior can be flexible. This is what Logan and collaborators propose to assess in a series of experiments on the great-tailed grackles, in a context of rapid range expansion. This pre-registration is integrated into this large research project and concerns more specifically the manipulability of the cognitive aspects of behavioral flexibility. Logan and collaborators will use reversal learning tests to test whether (i) behavioral flexibility is manipulatable, (ii) manipulating flexibility improves flexibility and problem solving in a new context, (iii) flexibility is repeatable within individuals, (iv) individuals are faster at problem solving as they progress through serial reversals. The pre-registration carefully details the hypotheses, their associated predictions and alternatives, and the plan of statistical analyses, including power tests. The ambitious program presented in this pre-registration has the potential to provide important pieces to better understand the mechanisms of species adaptability to new environments. | Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context? | Corina Logan, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Kelsey McCune | This is one of the first studies planned for our long-term research on the role of behavioral flexibility in rapid geographic range expansions. Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an impor... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2018-07-03 13:23:10 | View | ||

31 Jan 2019

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesAaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_causal.htmlFrom cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroecological patternsRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the distribution of species on earth is one of the fundamental challenges in ecology and evolution. For a long time, this challenge has mainly been addressed from a correlative point of view with a focus on abiotic factors determining a species abiotic niche (classical bioenvelope models; [1]). It is only recently that researchers have realized that behaviour and especially plasticity in behaviour may play a central role in determining species ranges and their dynamics [e.g., 2-5]. Blaisdell et al. propose to take this even one step further and to analyse how behavioural flexibility and possibly associated causal cognition impacts range dynamics. References | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan | This PREREGISTRATION has undergone one round of peer reviews. We have now revised the preregistration and addressed reviewer comments. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2018-08-20 11:09:48 | View | ||

26 Mar 2019

Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity?Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_exploration.htmlProbing behaviors correlated with behavioral flexibilityRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Behavioral plasticity, which is a subset of phenotypic plasticity, is an important component of foraging, defense against predators, mating, and many other behaviors. More specifically, behavioral flexibility, in this study, captures how quickly individuals adapt to new circumstances. In cases where individuals disperse to new environments, which often occurs in range expansions, behavioral flexibility is likely crucial to the chance that individuals can establish in these environments. Thus, it is important to understand how best to measure behavioral flexibility and how measures of such flexibility might vary across individuals and behavioral contexts and with other measures of learning and problem solving. | Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity? | Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | This is a PREREGISTRATION. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific file we are submitting is g_exploration.Rmd, which is easily accessible at GitHub at https://github.com/cor... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2018-09-27 03:35:12 | View | ||

05 Mar 2019

Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at inhibition?Corina Logan, Kelsey McCune, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Claudia Wascher http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_inhibition.htmlAdapting to a changing environment: advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibilityRecommended by Erin Vogel based on reviews by Simon Gingins and 2 anonymous reviewersBehavioral flexibility is essential for organisms to adapt to an ever-changing environment. However, the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility and understanding what traits makes a species better able to adapt behavior to new environments has been understudied. Logan and colleagues have proposed to use a series of experiments, using great-tailed grackles as a study species, to test four main hypotheses. These hypotheses are centered around exploring the relationship between behavioral flexibility and inhibition in grackles. This current preregistration is a part of a larger integrative research plan examining behavioral flexibility when faced with environmental change. In this part of the project they will examine specifically if individuals that are more flexible are also better at inhibiting: in other words: they will test the assumption that inhibition is required for flexibility. | Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at inhibition? | Corina Logan, Kelsey McCune, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Claudia Wascher | This is a PREREGISTRATION. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific file we are submitting is g_inhibition.Rmd, which is easily accessible at GitHub at https://github.com/cori... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Erin Vogel | 2018-10-12 18:36:00 | View | ||

07 Aug 2019

Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species?Corina Logan, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Kelsey McCune, Dieter Lukas http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexforaging.htmlUnderstanding geographic range expansions in human-dominated landscapes: does behavioral flexibility modulate flexibility in foraging and social behavior?Recommended by Julia Astegiano and Esther Sebastián González and Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Esther Sebastián González

Which biological traits modulate species distribution has historically been and still is one of the core questions of the macroecology and biogeography agenda [1, 2]. As most of the Earth surface has been modified by human activities [3] understanding the strategies that allow species to inhabit human-dominated landscapes will be key to explain species geographic distribution in the Anthropocene. In this vein, Logan et al. [4] are working on a long-term and integrative project aimed to investigate how great-tailed grackles rapidly expanded their geographic range into North America [4]. Particularly, they want to determine which is the role of behavioral flexibility, i.e. an individual’s ability to modify its behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience [5], in rapid geographic range expansions. The authors are already working in a set of complementary questions described in pre-registrations that have already been recommended at PCI Ecology: (1) Do individuals with greater behavioral flexibility rely more on causal cognition [6]? (2) Which are the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility [7]? (3) Does the manipulation of behavioral flexibility affect exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity [8]? (4) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility [9]? References [1] Gaston K. J. (2003) The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. | Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? | Corina Logan, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Kelsey McCune, Dieter Lukas | This is one of the first studies planned for our long-term research on the role of behavioral flexibility in rapid geographic range expansions. Project background: Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change ba... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Julia Astegiano | 2018-10-23 00:47:03 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle