Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id▲ | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Mar 2024

Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammalAmin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920Stress and stress hormones’ transmission from mothers to offspringRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Individuals can respond to environmental changes that they undergo directly (within-generation plasticity) but also through transgenerational plasticity, providing lasting effects that are transmitted to the next generations (Donelson et al. 2012; Munday et al. 2013; Kuijper & Hoyle 2015; Auge et al. 2017, Tariel et al. 2020). These parental effects can affect offspring via various mechanisms, notably via maternal transmission of hormones to the eggs or growing embryos (Mousseau & Fox 1998). While the effects of environmental quality may simply carry-over to the next generation (e.g., females in stressful environments give birth to offspring in poorer condition), parental effects may also be a mechanism that adjusts offspring phenotype in response to environmental variation and predictability, and thereby match offspring's phenotype to future environmental conditions (Gluckman et al. 2005; Marshall & Uller 2007; Dey et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2019), for example by preparing their offspring to an expected stressful environment. When females experience stress during gestation or egg formation, elevations in glucocorticoids (GC) are expected to affect offspring phenotype in many ways, from the offspring's own GC levels, to their growth and survival (Sheriff et al. 2017). This is a well established idea, but how strong is the evidence for this? A meta-analysis on birds found no clear effect of corticosterone manipulation on offspring traits (38 studies on 9 bird species for corticosterone manipulation; Podmokła et al. 2018). Another meta-analysis including 14 vertebrate species found no clear effect of prenatal stress on offspring GC (Thayer et al. 2018). Finally, a meta-analysis on wild vertebrates (23 species) found no clear effect of GC-mediated maternal effects on offspring traits (MacLeod et al. 2021). As often when facing such inconclusive results, context dependence has been suggested as one potential reason for such inconsistencies, for exemple sex specific effects (Groothuis et al. 2019, 2020). However, sex specific measures on offspring are scarce (Podmokła et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature available is still limited to a few, mostly “model” species. With their study, Amin et al. (2024) show the way to improve our understanding on GC transmission from mother to offspring and its effects in several aspects. First they used innovative non-invasive methods (which could broaden the range of species available to study) by quantifying cortisol metabolites from faecal samples collected from pregnant females, as proxy for maternal GC level, and relating it to GC levels from hairs of their neonate offspring. Second they used a free ranging large mammal (taxa from which literature is missing): the fallow deer (Dama dama). Third, they provide sex specific measures of GC levels. And finally but importantly, they are exemplary in their transparency regarding 1) the exploratory nature of their study, 2) their statistical thinking and procedure, and 3) the study limitations (e.g., low sample size and high within individual variation of measurements). I hope this study will motivate more research (on the fallow deer, and on other species) to broaden and strengthen our understanding of sex specific effects of maternal stress and CG levels on offspring phenotype and fitness. References Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., & Ciuti, S. (2024). Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and foetal glucocorticoids in a free-ranging large mammal. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920 Auge, G.A., Leverett, L.D., Edwards, B.R. & Donohue, K. (2017). Adjusting phenotypes via within-and across-generational plasticity. New Phytologist, 216, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14495 Dey, S., Proulx, S.R. & Teotonio, H. (2016). Adaptation to temporally fluctuating environments by the evolution of maternal effects. PLoS biology, 14, e1002388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002388 Donelson, J.M., Munday, P.L., McCormick, M.I. & Pitcher, C.R. (2012). Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1323 Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A. & Spencer, H.G. (2005). Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001 Groothuis, Ton GG, Bin-Yan Hsu, Neeraj Kumar, and Barbara Tschirren. "Revisiting mechanisms and functions of prenatal hormone-mediated maternal effects using avian species as a model." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374, no. 1770 (2019): 20180115. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0115 Groothuis, Ton GG, Neeraj Kumar, and Bin-Yan Hsu. "Explaining discrepancies in the study of maternal effects: the role of context and embryo." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36 (2020): 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.10.006 Kuijper, B. & Hoyle, R.B. (2015). When to rely on maternal effects and when on phenotypic plasticity? Evolution, 69, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12635 MacLeod, Kirsty J., Geoffrey M. While, and Tobias Uller. "Viviparous mothers impose stronger glucocorticoid‐mediated maternal stress effects on their offspring than oviparous mothers." Ecology and Evolution 11, no. 23 (2021): 17238-17259. Marshall, D.J. & Uller, T. (2007). When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos, 116, 1957–1963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x Mousseau, T.A. & Fox, C.W. (1998). Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press. Munday, P.L., Warner, R.R., Monro, K., Pandolfi, J.M. & Marshall, D.J. (2013). Predicting evolutionary responses to climate change in the sea. Ecology Letters, 16, 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12185 Podmokła, Edyta, Szymon M. Drobniak, and Joanna Rutkowska. "Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method–a meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 93, no. 3 (2018): 1499-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12406 Sheriff, M. J., Bell, A., Boonstra, R., Dantzer, B., Lavergne, S. G., McGhee, K. E., MacLeod, K. J., Winandy, L., Zimmer, C., & Love, O. P. (2017). Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105 Tariel, Juliette, Sandrine Plénet, and Émilien Luquet. "Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (2020): 548660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.548660 Thayer, Zaneta M., Meredith A. Wilson, Andrew W. Kim, and Adrian V. Jaeggi. "Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: A phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species." Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 4942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23169-w Yin, J., Zhou, M., Lin, Z., Li, Q.Q. & Zhang, Y.-Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects benefit offspring across diverse environments: a meta-analysis in plants and animals. Ecology letters, 22, 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13373 | Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammal | Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Maternal phenotypes can have long-term effects on offspring phenotypes. These maternal effects may begin during gestation, when maternal glucocorticoid (GC) levels may affect foetal GC levels, thereby having an orga... | Evolutionary ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Physiology, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-06-05 09:06:56 | View | ||

03 Jan 2024

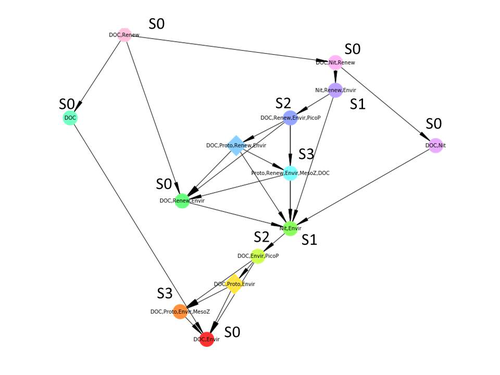

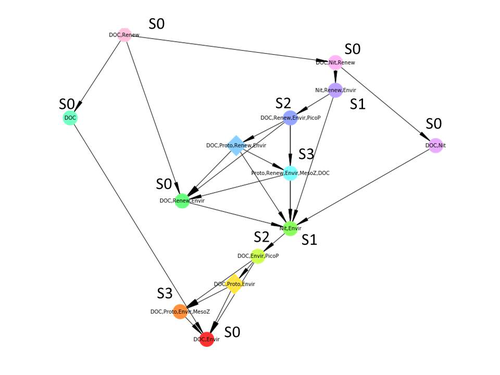

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changesCedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networksRecommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewerModelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks. Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model. The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed. The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics. Reference Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055 | Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes | Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy | <p>Trophic interaction networks are notoriously difficult to understand and to diagnose (i.e., to identify contrasted network functioning regimes). Such ecological networks have many direct and indirect connections between species, and these conne... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Interaction networks, Microbial ecology & microbiology | Francis Raoul | Tim Coulson | 2023-07-03 10:42:34 | View |

19 Mar 2024

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

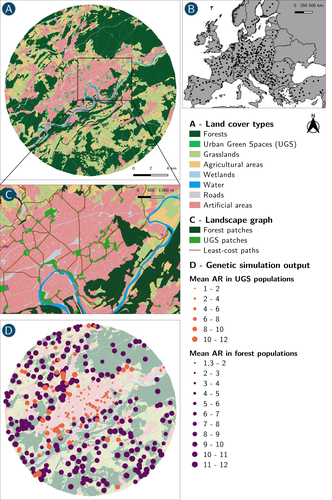

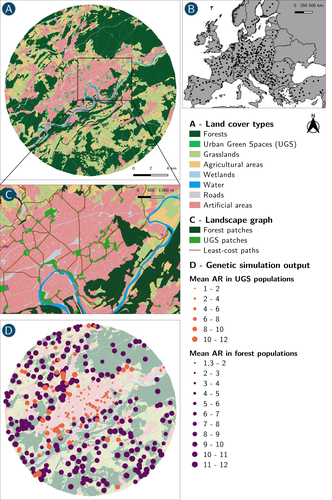

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View | |

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

23 Oct 2023

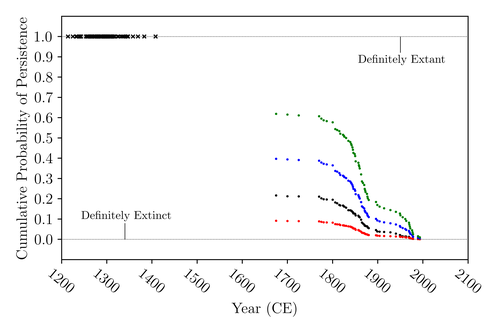

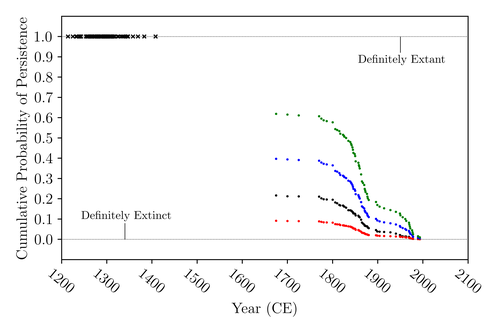

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

02 Jan 2024

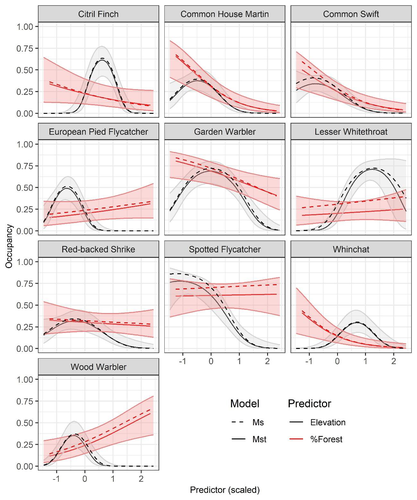

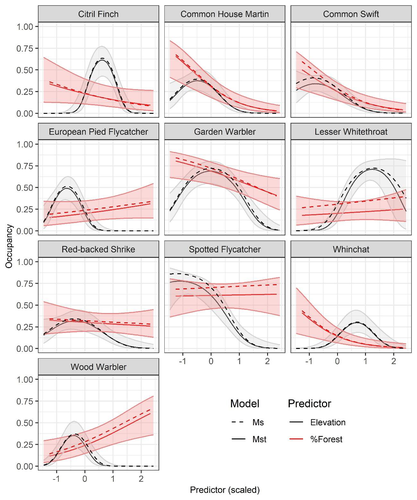

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

12 Jan 2024

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonisAlexius Folk, Adele Mennerat https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695Marking invertebrates using RFID tagsRecommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer

Guiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically. The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it. References Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013 Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008. Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695 Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082 Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900 | Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse *Lepeophtheirus salmonis* | Alexius Folk, Adele Mennerat | <p style="text-align: justify;">Monitoring individuals within populations is a cornerstone in evolutionary ecology, yet individual tracking of invertebrates and particularly parasitic organisms remains rare. To address this gap, we describe here a... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Marine ecology, Parasitology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-09-04 15:25:08 | View | |

30 May 2024

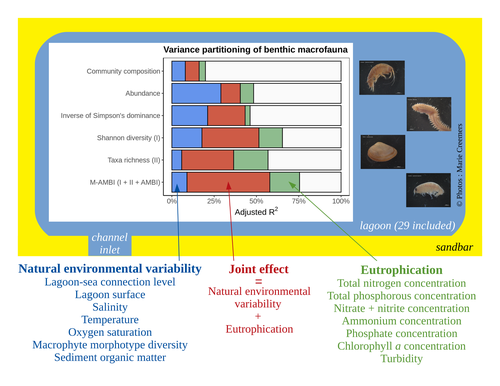

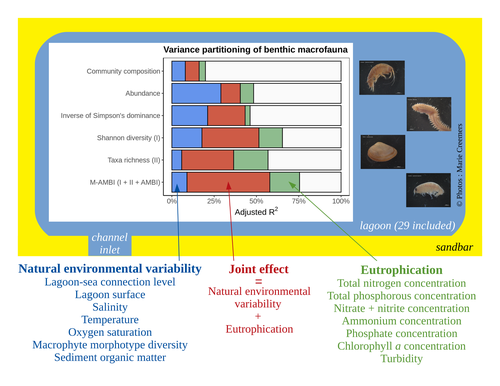

Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoonsAuriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.18.504439Untangling Eutrophication Effects on Coastal Lagoon EcosystemsRecommended by Nathalie Niquil based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright

Disentangling the effects on ecosystem structure and functioning of natural and human-induced impacts in transitional waters is a great challenge in coast ecology. This is due to the observation that the ecosystems of transitional waters are naturally dynamic systems with characteristics of stressed systems. For example, the benthic communities present low species richness and high abundance of species with a high tolerance to variations, e.g., salinity. This general observation is known as the paradigm of the “Transitional Waters Quality Paradox” (Zaldívar et al., 2008) derived from the previously described “Estuarine Quality Paradox” (Elliott and Quintino, 2007). In Jones et al. (2024) “Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons”, a great diversity of lagoons is analyzed to disentangle the effects of eutrophication from those of natural environmental variability on benthic macroinvertebrates and understanding the links between environmental variables affecting benthic macroinvertebrates. These authors use a very elegant set of numerical approaches, including correlograms, linear models and variance partitioning. They apply this suite to a dataset of macrobenthic invertebrate abundances and environmental variables from 29 Mediterranean coastal lagoons in France. Through this suite of analyses, they demonstrate the strong complexity of the mechanisms interplaying in a situation of eutrophication on lagoon macrobenthos. The mechanisms involved are direct, like toxicity, or indirect, for example, through modifications of the sediment's biogeochemistry. Such a result on the different interactions involved is very important in the context of the search for indicators to define ecosystem status. Improving the definition of metrics is essential in environmental management decisions. References Elliott, M. and Quintino, V. (2007) The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.02.003 Zaldívar, J. (2008). Eutrophication in transitional waters: an overview. https://doi.org/10.1285/I18252273V2N1P1 | Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons | Auriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are transitional ecosystems that host a unique diversity of species and support many ecosystem services. Owing to their position at the interface between land and sea, they are also subject to increa... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Marine ecology | Nathalie Niquil | Matthew J. Pruden | 2023-09-08 11:26:01 | View |

01 Mar 2024

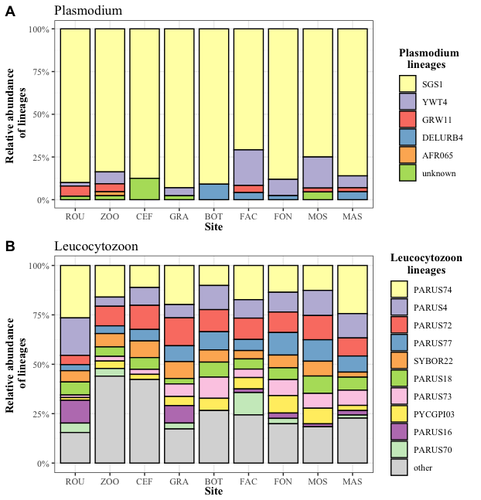

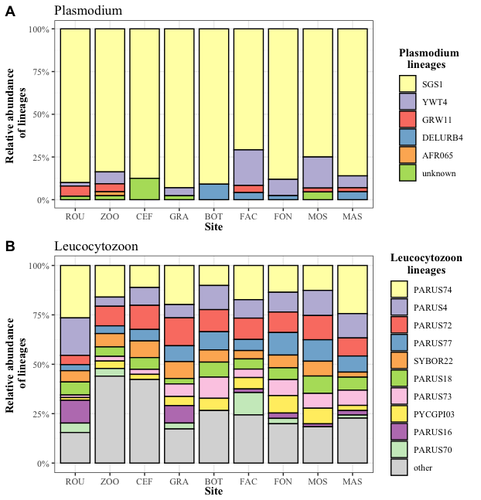

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

15 Feb 2024

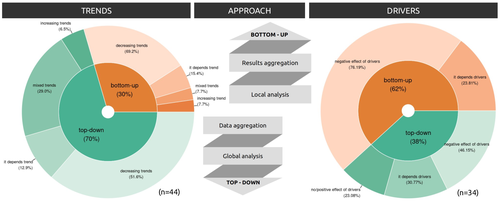

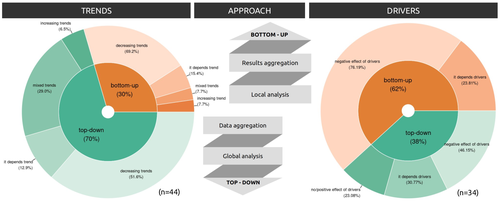

Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trendsMaelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3HUnraveling the Complexity of Global Biodiversity Dynamics: Insights and ImperativesRecommended by Paulo Borges based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer

Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across terrestrial and marine ecosystems, driven by various processes that degrade habitats and threaten species with extinction. Despite the urgency of this issue, empirical studies present a mixed picture, with some indicating declining trends while others show more complex patterns. In a recent effort to better understand global biodiversity dynamics, Boennec et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive literature review examining temporal trends in biodiversity. Their analysis reveals that reviews and meta-analyses, coupled with the use of global indicators, tend to report declining trends more frequently. Additionally, the study underscores a critical gap in research: the scarcity of investigations into the combined impact of multiple pressures on biodiversity at a global scale. This lack of understanding complicates efforts to identify the root causes of biodiversity changes and develop effective conservation strategies. This study serves as a crucial reminder of the pressing need for long-term biodiversity monitoring and large-scale conservation studies. By filling these gaps in knowledge, researchers can provide policymakers and conservation practitioners with the insights necessary to mitigate biodiversity loss and safeguard ecosystems for future generations. References Boennec, M., Dakos, V. & Devictor, V. (2023). Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trend. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3H

| Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trends | Maelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor | <p>Populations and ecological communities are changing worldwide, and empirical studies exhibit a mixture of either declining or mixed trends. Confusion in global biodiversity trends thus remains while assessing such changes is of major social, po... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Meta-analyses | Paulo Borges | 2023-09-20 11:10:25 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle