Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

07 Jun 2023

High intraspecific growth variability despite strong evolutionary heritage in a neotropical forestSylvain Schmitt, Bruno Hérault, Géraldine Derroire https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.27.501745Environmental and functional determinants of tree performance in a neotropical forest: the imprint of evolutionary legacy on growth strategiesRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Camille Girard and Jelena Pantel based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker, Camille Girard and Jelena Pantel

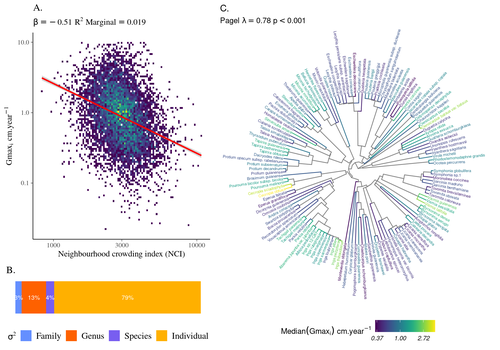

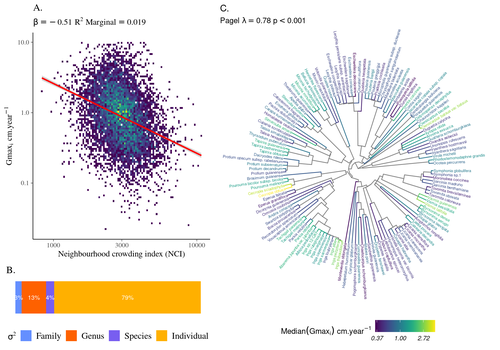

The hyperdiverse tropical forests have long fascinated ecologists because the fact that so many species persist at a low density at a local scale remains hard to explain. Both niche-based and neutral hypotheses have been tested, primarily based on analyzing the taxonomic composition of tropical forest plots (Janzen 1970; Hubbell 2001). Studies of the functional and phylogenetic structure of tropical tree communities have further aimed to better assess the importance of niche-based processes. For instance, Baraloto et al. (2012) found that co-occurring species were functionally and phylogenetically more similar in a neotropical forest, suggesting a role of environmental filtering. Likewise, Schmitt et al. (2021) found the influence of environmental filtering on the functional composition of an Indian rainforest. Yet these studies evidenced non-random trait-environment association based on the composition of assemblages only (in terms of occurrences and abundances). A major challenge remains to further address whether and how tree performance varies among species and individuals in tropical forests. Functional traits are related to components of individual fitness (Violle et al. 2007). Recently, more and more emphasis has been put on examining the relationship between functional trait values and demographic parameters (Salguero-Gómez et al. 2018), in order to better understand how functional trait values determine species population dynamics and abundances in assemblages. Fortunel et al. (2018) found an influence of functional traits on species growth variation related to topography, and less clearly to neighborhood density (crowding). Poorter et al. (2018) observed 44% of trait variation within species in a neotropical forest. Although individual trait values would be expected to be better predictors of performance than average values measured at the species level, Poorter et al still found a poor relationship. Schmitt et al. (2023) examined how abiotic conditions and biotic interactions (considering neighborhood density) influenced the variation of individual potential tree growth, in a tropical forest plot located in French Guiana. They also considered the link between species-averaged values of growth potential and functional traits. Schmitt et al. (2023) found substantial variation in growth potential within species, that functional traits explained 40% of the variation of species-averaged growth and, noticeably, that the taxonomic structure (used as random effect in their model) explained a third of the variation in individual growth. Although functional traits of roots, wood and leaves could predict a significant part of species growth potential, much variability of tree growth occurred within species. Intraspecific trait variation can thus be huge in response to changing abiotic and biotic contexts across individuals. The information on phylogenetic relationships can still provide a proxy of the integrated phenotypic variation that is under selection across the phylogeny, and determine a variation in growth strategies among individuals. The similarity of the phylogenetic structure suggests a joint selection of these growth strategies and related functional traits during events of convergent evolution. Baraloto et al. (2012) already noted that phylogenetic distance can be a proxy of niche overlap in tropical tree communities. Here, Schmitt et al. further demonstrate that evolutionary heritage is significantly related to individual growth variation, and plead for better acknowledging this role in future studies. While the role of fitness differences in tropical tree community dynamics remained to be assessed, the present study provides new evidence that individual growth does vary depending on evolutionary relationships, which can reflect the roles of selection and adaptation on growth strategies. Therefore, investigating both the influence of functional traits and phylogenetic relationships on individual performance remains a promising avenue of research, for functional and community ecology in general. REFERENCES Baraloto, Christopher, Olivier J. Hardy, C. E. Timothy Paine, Kyle G. Dexter, Corinne Cruaud, Luke T. Dunning, Mailyn-Adriana Gonzalez, et al. 2012. « Using functional traits and phylogenetic trees to examine the assembly of tropical tree communities ». Journal of Ecology, 100: 690‑701. | High intraspecific growth variability despite strong evolutionary heritage in a neotropical forest | Sylvain Schmitt, Bruno Hérault, Géraldine Derroire | <p style="text-align: justify;">Individual tree growth is a key determinant of species performance and a driver of forest dynamics and composition. Previous studies on tree growth unravelled the variation in species growth as a function of demogra... |  | Community ecology, Demography, Population ecology | François Munoz | Jelena Pantel, David Murray-Stoker | 2022-08-01 14:29:04 | View |

05 Nov 2019

Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population.Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. https://doi.org/10.1101/474874Defoliation induces a trade-off between reproduction and growth in a southern population of BeechRecommended by Georges Kunstler based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersIndividuals ability to withstand abiotic and biotic stresses is crucial to the maintenance of populations at climate edge of tree species distribution. We start to have a detailed understanding of tree growth response and to a lesser extent mortality response in these populations. In contrast, our understanding of the response of tree fecundity and recruitment remains limited because of the difficulty to monitor it at the individual tree level in the field. Tree recruitment limitation is, however, crucial for tree population dynamics [1-2]. References [1] Clark, J. S. et al. (1999). Interpreting recruitment limitation in forests. American Journal of Botany, 86(1), 1-16. doi: 10.2307/2656950 | Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population. | Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio, Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Valentin Journé, Matthieu Lingrand, Jean-André Magdalou, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Hendrik Davi, Elodie Magnanou. | <p>1. Although droughts and heatwaves have been associated to increased crown defoliation, decreased growth and a higher risk of mortality in many forest tree species, their impact on tree reproduction and forest regeneration still remains underst... |  | Climate change, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Molecular ecology, Physiology, Population ecology | Georges Kunstler | 2018-11-20 13:29:42 | View | |

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View | ||

06 May 2021

Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changesThibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021A lack of clear dietary differences between ontogenetic stages of invasive slippersnails provides important insights into resource use and potential inter- and intra-specific competitionRecommended by Matthew Bracken based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe slippersnail (Crepidula fornicata), originally from the eastern coast of North America, has invaded European coastlines from Norway to the Mediterranean Sea [1]. This species is capable of achieving incredibly high densities (up to several thousand individuals per square meter) and likely has major impacts on a variety of community- and ecosystem-level processes, including alteration of carbon and nitrogen fluxes and competition with native suspension feeders [2]. Given this potential for competition, it is important to understand the diet of C. fornicata and its potential overlap with native species. However, previous research on the diet of C. fornicata and related species suggests that the types of food consumed may change with age [3, 4]. This species has an unusual reproductive strategy. It is a sequential hermaphrodite, which begins life as a somewhat mobile male but eventually slows down to become sessile. Sessile individuals form stacks of up to 10 or more individuals, with larger individuals on the bottom of the stack, and decreasingly smaller individuals piled on top. Snails at the bottom of the stack are female, whereas snails at the top of the stack are male; when the females die, the largest males become female [5]. Thus, understanding these potential ontogenetic dietary shifts has implications for both intraspecific (juvenile vs. male vs. female) and interspecific competition associated with an abundant, invasive species. To this end, Androuin and colleagues evaluated the stable-isotope (d13C and d15N) and fatty-acid profiles of food sources and different life-history stages of C. fornicata [6]. Based on previous work highlighting the potential for life-history changes in the diet of this species [3,4], they hypothesized that C. fornicata would shift its diet as it aged and predicted that this shift would be reflected in changes in its stable-isotope and fatty-acid profiles. The authors found that potential food sources (biofilm, suspended particulate organic matter, and superficial sedimentary organic matter) differed substantially in both stable-isotope and fatty-acid signatures. However, whereas fatty-acid profiles changed substantially with age, there was no shift in the stable-isotope signatures. Because stable-isotope differences between food sources were not reflected in differences between life-history stages, the authors conservatively concluded that there was insufficient evidence for a diet shift with age. The ontogenetic shifts in fatty-acid profiles were intriguing, but the authors suggested that these reflected age-related physiological changes rather than changes in diet. The authors’ work highlights the need to consider potential changes in the roles of invasive species with age, especially when evaluating interactions with native species. In this case, C. fornicata consumed a variety of food sources, including both benthic and particulate organic matter, regardless of age. The carbon stable-isotope signature of C. fornicata overlaps with those of several native suspension- and deposit-feeding species in the region [7], suggesting the possibility of resource competition, especially given the high abundances of this invader. This contribution demonstrates the potential difficulty of characterizing the impacts of an abundant invasive species with a complex life-history strategy. Like many invasive species, C. fornicata appears to be a dietary generalist, which likely contributes to its success in establishing and thriving in a variety of locations [8].

References [1] Blanchard M (1997) Spread of the slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L. 1758) in Europe. Current state dans consequences. Scientia Marina, 61, 109–118. Open Access version : https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00423/53398/54271.pdf [2] Martin S, Thouzeau G, Chauvaud L, Jean F, Guérin L, Clavier J (2006) Respiration, calcification, and excretion of the invasive slipper limpet, Crepidula fornicata L.: Implications for carbon, carbonate, and nitrogen fluxes in affected areas. Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 1996–2007. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.1996 [3] Navarro JM, Chaparro OR (2002) Grazing–filtration as feeding mechanisms in motile specimens of Crepidula fecunda (Gastropoda: Calyptraeidae). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 270, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00013-8 [4] Yee AK, Padilla DK (2015) Allometric Scaling of the Radula in the Atlantic Slippersnail Crepidula fornicata. Journal of Shellfish Research, 34, 903–907. https://doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0320 [5] Collin R (1995) Sex, Size, and Position: A Test of Models Predicting Size at Sex Change in the Protandrous Gastropod Crepidula fornicata. The American Naturalist, 146, 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/285826 [6] Androuin T, Dubois SF, Hubas C, Lefebvre G, Grand FL, Schaal G, Carlier A (2021) Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.229021, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021 [7] Dauby P, Khomsi A, Bouquegneau J-M (1998) Trophic Relationships within Intertidal Communities of the Brittany Coasts: A Stable Carbon Isotope Analysis. Journal of Coastal Research, 14, 1202–1212. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4298880 [8] Machovsky-Capuska GE, Senior AM, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D (2016) The Multidimensional Nutritional Niche. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 31, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.009

| Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes | Thibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata is a common and widespread invasive gregarious species along the European coast. Among its life-history traits, well-documented ontogenic changes in behavior (i.e., motile male... |  | Food webs, Life history, Marine ecology | Matthew Bracken | 2020-08-01 23:55:57 | View | |

03 Oct 2023

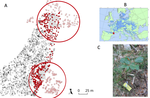

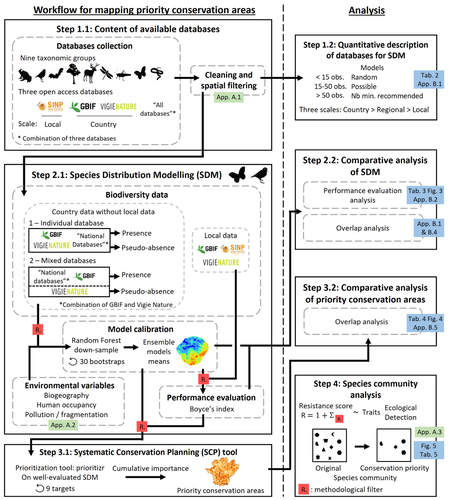

Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sourcesThibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999Biodiversity databases are ever more numerous, but can they be used reliably for Species Distribution Modelling?Recommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Proposing efficient guidelines for biodiversity conservation often requires the use of forecasting tools. Species Distribution Models (SDM) are more and more used to predict how the distribution of a species will react to environmental change, including any large-scale management actions that could be implemented. Their use is also boosted by the increase of publicly available biodiversity databases[1]. The now famous aphorism by George Box "All models are wrong but some are useful"[2] very well summarizes that the outcome of a model must be adjusted to, and will depend on, the data that are used to parameterize it. The question of the reliability of using biodiversity databases to parameterize biodiversity models such as SDM –but the question would also apply to other kinds of biodiversity models, e.g. Population Viability Analysis models[3]– is key to determine the confidence that can be placed in model predictions. This point is often overlooked by some categories of biodiversity conservation stakeholders, in particular the fact that some data were collected using controlled protocols while others are opportunistic. In this study[4], the authors use a collection of databases covering a range of species as well as of geographic scales in France and using different data collection and validation approaches as a case study to evaluate the impact of data quality when performing Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Among their conclusions, the fact that a large-scale database (what they call the “country” level) is necessary to reliably parameterize SDM. Besides this and other conclusions of their study, which are likely to be in part specific to their case study –unfortunately for its conservation, biodiversity is complex and varies a lot–, the merit of this work lies in the approach used to test the impact of data on model predictions. References 1. Feng, X. et al. A review of the heterogeneous landscape of biodiversity databases: Opportunities and challenges for a synthesized biodiversity knowledge base. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31, 1242–1260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13497 2. Box, G. E. P. Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building. in Robustness in Statistics (eds. Launer, R. L. & Wilkinson, G. N.) 201–236 (Academic Press, 1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-438150-6.50018-2. 3. Beissinger, S. R. & McCullough, D. R. Population Viability Analysis. (The University of Chicago Press, 2002). 4. Ferraille, T., Kerbiriou, C., Bigard, C., Claireau, F. & Thompson, J. D. (2023) Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999 | Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources | Thibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson | <p>Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of land-use planning is a fundamental tool to minimize environmental impacts of artificialization. In this context, Systematic Conservation Planning (SCP) tools based on Species Distribution Models (SDM)... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-05-11 09:41:05 | View | |

16 Jun 2023

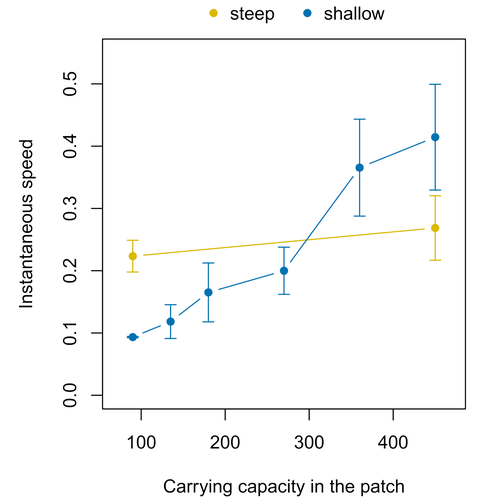

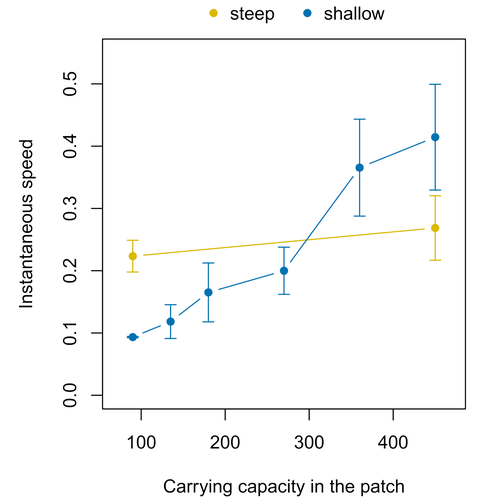

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansionThibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environmentsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007). Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients). Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011). The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions. REFERENCES Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746 Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1 Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431. Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255 Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107 Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x | Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion | Thibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken | <p>Demographic processes that occur at the local level, such as positive density dependence in growth or dispersal, are known to shape population range expansion, notably by linking carrying capacity to invasion speed. As a result of these process... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Joaquín Hortal | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-11-16 15:52:08 | View |

01 Oct 2023

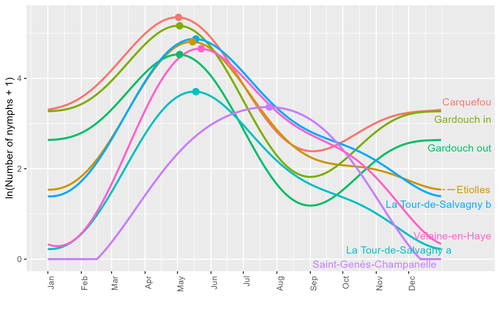

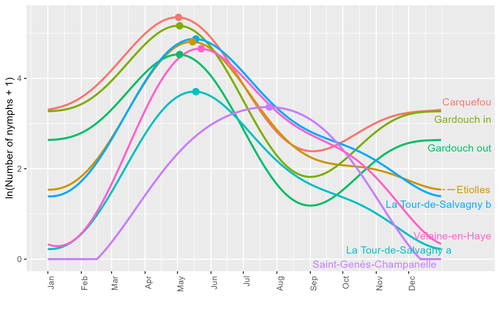

Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climateThierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Verheyden, Gwenaёl Vourc’h, Karine Chalvet-Monfray, Albert Agoulon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416Assessing seasonality of tick abundance in different climatic regionsRecommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne pathogens are considered as one of the major threats to public health – Lyme borreliosis being a well-known example of such disease. Global change – from climate change to changes in land use or invasive species – is playing a role in the increased risk associated with these pathogens. An important aspect of our knowledge of ticks and their associated pathogens is seasonality – one component being the phenology of within-year tick occurrences. This is important both in terms of health risk – e.g., when is the risk of encountering ticks high – and ecological understanding, as tick dynamics may depend on the weather as well as different hosts with their own dynamics and habitat use. Hoch et al. (2023) provide a detailed data set on the phenology of one species of tick, Ixodes ricinus, in 6 different locations of France. Whereas relatively cool sites showed a clear peak in spring-summer, warmer sites showed in addition relatively high occurrences in fall-winter, with a minimum in late summer-early fall. Such results add robust data to the existing evidence of the importance of local climatic patterns for explaining tick phenology. Recent analyses have shown that the phenology of Lyme borreliosis has been changing in northern Europe in the last 25 years, with seasonal peaks in cases occurring now 6 weeks earlier (Goren et al. 2023). The study by Hoch et al. (2023) is of too short duration to establish temporal changes in phenology (“only” 8 years, 2014-2021, see also Wongnak et al 2021 for some additional analyses; given the high year-to-year variability in weather, establishing phenological changes often require longer time series), and further work is needed to get better estimates of these changes and relate them to climate, land-use, and host density changes. Moreover, the phenology of ticks may also be related to species-specific tick phenology, and different tick species do not respond to current changes in identical ways (see for example differences between the two Ixodes species in Finland; Uusitalo et al. 2022). An efficient surveillance system requires therefore an adaptive monitoring design with regard to the tick species as well as the evolving causes of changes. References Goren, A., Viljugrein, H., Rivrud, I. M., Jore, S., Bakka, H., Vindenes, Y., & Mysterud, A. (2023). The emergence and shift in seasonality of Lyme borreliosis in Northern Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1993), 20222420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2420 Hoch, T., Madouasse, A., Jacquot, M., Wongnak, P., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Agoulon, A. (2023). Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climate. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416 Uusitalo, R., Siljander, M., Lindén, A., Sormunen, J. J., Aalto, J., Hendrickx, G., . . . Vapalahti, O. (2022). Predicting habitat suitability for Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Finland. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05410-8 Wongnak, P., Bord, S., Jacquot, M., Agoulon, A., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Chalvet-Monfray, K. (2022). Meteorological and climatic variables predict the phenology of Ixodes ricinus nymph activity in France, accounting for habitat heterogeneity. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11479-z | Seasonality of host-seeking *Ixodes ricinus* nymph abundance in relation to climate | Thierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Ve... | <p style="text-align: justify;">There is growing concern about climate change and its impact on human health. Specifically, global warming could increase the probability of emerging infectious diseases, notably because of changes in the geographic... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-10-14 18:43:56 | View | |

20 Feb 2023

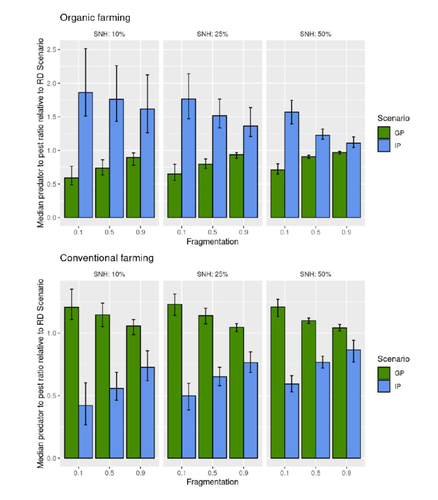

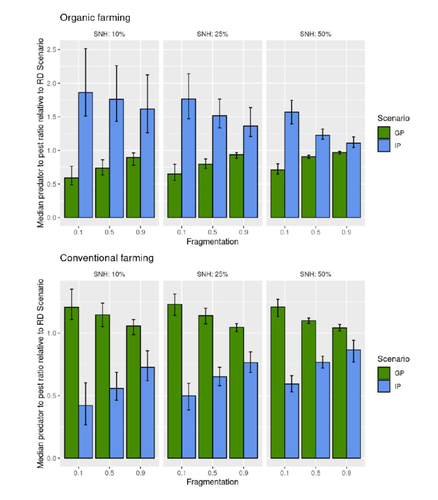

Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approachThomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006Towards model-guided organic farming expansion for crop pest managementRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart based on reviews by Julia Astegiano, Lionel Hertzog and Sylvain Bart

Reduce the impact the intensification of human activities has on the environmental is the challenge the humanity faces today, a major challenge that could be compared to climbing Everest without an oxygen supply. Indeed, over-population, pollution, burning fossil fuels, and deforestation are all evils which have had hugely detrimental effects on the environment such as climate change, soil erosion, poor air quality, and scarcity of drinking water to name but a few. In response to the ever-growing consumer demand, agriculture has intensified massively along with a drastic increase in the use of chemicals to ensure an adequate food supply while controlling crop pests. In this context, to address the disastrous effects of the intensive usage of pesticides on both human health and biodiversity, organic farming (OF) revealed as a miracle remedy with multiple benefits. Delattre et al. (2023) present a powerful modelling approach to decipher the crossed effects of the landscape structure and the OF expansion scenario on the pest abundance, both in organic and conventional (CF) crop fields. To this end, the authors ingeniously combined a grid-based landscape model with a spatially explicit predator-pest model. Based on an extensive in silico simulation process, they explore a diversity of landscape structures differing in their amount of semi-natural habitats (SHN) and in their fragmentation, to finally propose a ranking of various expansion scenarios according to the pest control methods in organic farming as well as to the pest and predators’ dissemination capacities. In total, 9 landscape structures (3 proportions of SHN x 3 fragmentation levels) were crossed with 3 expansion scenarios (RD = a random distribution of OF and CF in the grid; IP = isolated CF are converted; GP = CF within aggregates are converted), 4 pest management practices, 3 initial densities and 36 biological parameter combinations driving the predator’ and pest’s population dynamics. This exhaustive exploration of possible combinations of landscape and farming practices highlighted the main drivers of the various OF expansion scenarios, such as increased spillover of predators in isolated OF/CF fields, increased pest management efficiency in large patches of CF and the importance of the distance between OF and CF. In the end, this study brings to light the crucial role that landscape planning plays when OF practices have limited efficiency on pests. It also provides convincing arguments to the fact that converting to organic isolated CF as a priority seems to be the most promising scenario to limit pest densities in CF crops while improving predator to pest ratios (considered as a proxy of conservation biological control) in OF ones without increasing pest densities. Once further completed with model calibration validation based on observed life history traits data for both predators and pests, this work should be very helpful in sustaining policy makers to convince farmers of engaging in organic farming. REFERENCES Delattre T, Memah M-M, Franck P, Valsesia P, Lavigne C (2023) Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach. bioRxiv, 2022.05.31.494006, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.31.494006 | Best organic farming deployment scenarios for pest control: a modeling approach | Thomas Delattre, Mohamed-Mahmoud Memah, Pierre Franck, Pierre Valsesia, Claire Lavigne | <p style="text-align: justify;">Organic Farming (OF) has been expanding recently around the world in response to growing consumer demand and as a response to environmental concerns. Its share of agricultural landscapes is expected to increase in t... |  | Agroecology, Biological control, Landscape ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-06-03 11:41:14 | View | |

16 Jun 2020

Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback frameworkTim Coulson https://doi.org/10.1101/509067Stasis and the phenotypic gambitRecommended by Tom Van Dooren based on reviews by Jacob Johansson, Katja Räsänen and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint "Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework" by Coulson (2020) presents a general framework for evolutionary ecology, useful to interpret patterns of selection and evolutionary responses to environmental transitions. The paper is written in an accessible and intuitive manner. It reviews important concepts which are at the heart of evolutionary ecology. Together, they serve as a worldview which you can carry with you to interpret patterns in data or observations in nature. I very much appreciate it that Coulson (2020) presents his personal intuition laid bare, the framework he uses for his research and how several strong concepts from theoretical ecology fit in there. Overviews as presented in this paper are important to understand how we as researchers put the pieces together. References [1] Coulson, T. (2020) Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework. bioRxiv, 509067, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/509067 | Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework | Tim Coulson | <p>I provide a general framework for linking ecology and evolution. I start from the fact that individuals require energy, trace molecules, water, and mates to survive and reproduce, and that phenotypic resource accrual traits determine an individ... |  | Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology | Tom Van Dooren | 2019-01-03 10:05:16 | View | |

01 Mar 2022

Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiringTimothée Poisot https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2How to evaluate and interpret the contribution of species turnover and interaction rewiring when comparing ecological networks?Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer

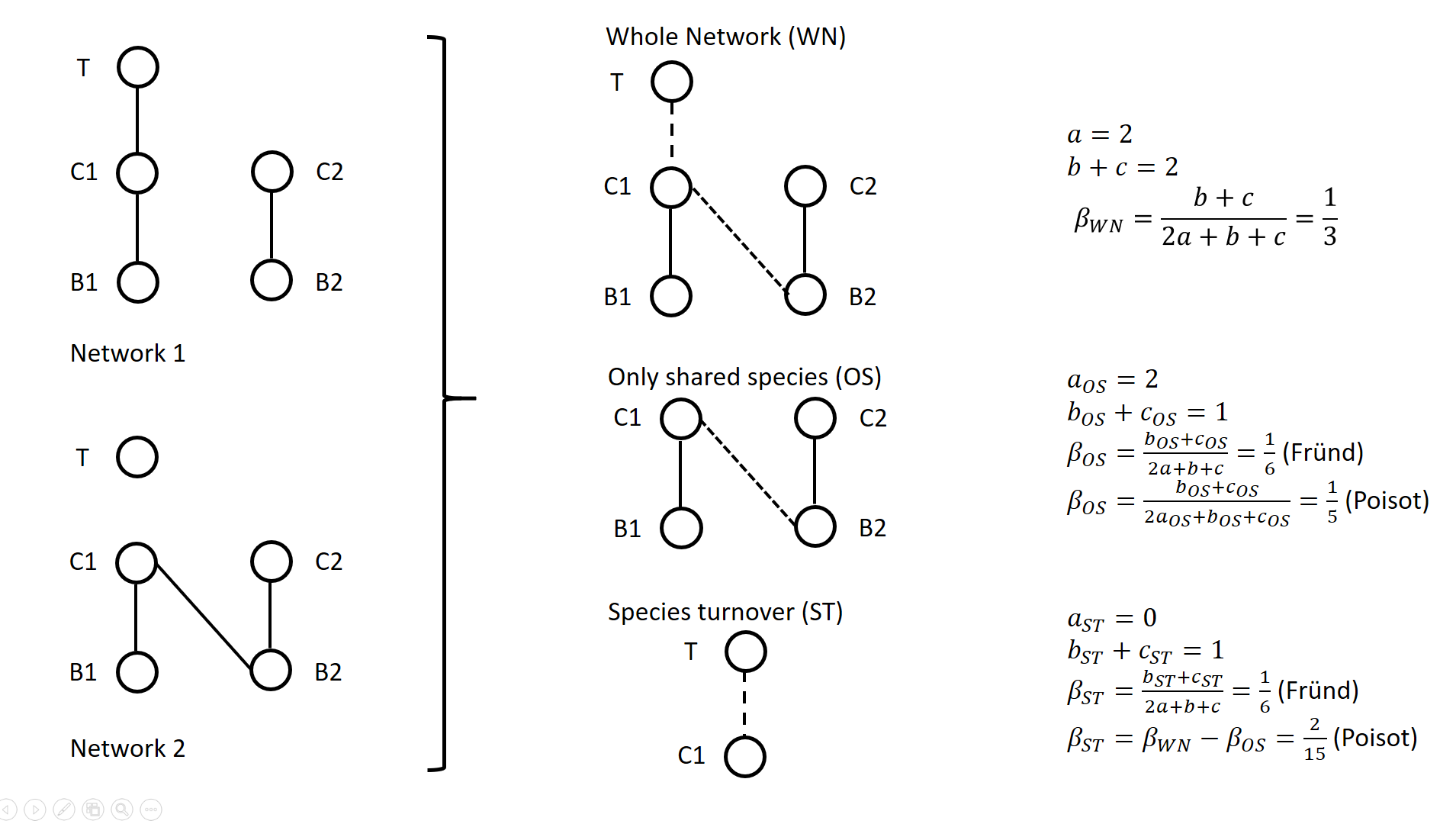

A network includes a set of vertices or nodes (e.g., species in an interaction network), and a set of edges or links (e.g., interactions between species). Whether and how networks vary in space and/or time are questions often addressed in ecological research. Two ecological networks can differ in several extents: in that species are different in the two networks and establish new interactions (species turnover), or in that species that are present in both networks establish different interactions in the two networks (rewiring). The ecological meaning of changes in network structure is quite different according to whether species turnover or interaction rewiring plays a greater role. Therefore, much attention has been devoted in recent years on quantifying and interpreting the relative changes in network structure due to species turnover and/or rewiring. Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to partition the global variation in structure between networks, \( \beta_{WN} \) (WN = Whole Network) into two terms: \( \beta_{OS} \) (OS = Only Shared species) and \( \beta_{ST} \) (ST = Species Turnover), such as \( \beta_{WN} = \beta_{OS} + \beta_{ST} \). The calculation lays on enumerating the interactions between species that are common or not to two networks, as illustrated on Figure 1 for a simple case. Specifically, Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to use a Sorensen type measure of network dissimilarity, i.e., \( \beta_{WN} = \frac{a+b+c}{(2a+b+c)/2} -1=\frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} \) , where \( a \) is the number of interactions shared between the networks, while \( b \) and \( c \) are interaction numbers unique to one and the other network, respectively. \( \beta_{OS} \) is calculated based on the same formula, but only for the subnetworks including the species common to the two networks, in the form \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a_{OS}+b_{OS}+c_{OS}} \) (e.g., Fig. 1). \( \beta_{ST} \) is deduced by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and represents in essence a "dissimilarity in interaction structure introduced by dissimilarity in species composition" (Poisot et al. 2012).

Figure 1. Ecological networks exemplified in Fründ (2021) and discussed in Poisot (2022). a is the number of shared links (continuous lines in right figures), while b+c is the number of edges unique to one or the other network (dashed lines in right figures). Alternatively, Fründ (2021) proposed to define \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a+b+c} \) and \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} \), where \( b_{ST}=b-b_{OS} \) and \( c_{ST}=c-c_{OS} \) , so that the components \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) have the same denominator. In this way, Fründ (2021) partitioned the count of unique \( b+c=b_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST} \) interactions, so that \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) sums to \( \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} = \frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} = \beta_{WN} \). Fründ (2021) advocated that this partition allows a more sensible comparison of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \), in terms of the number of links that contribute to each component. For instance, let us consider the networks 1 and 2 in Figure 1 (left panel) such as \( a_{OS}=2 \) (continuous lines in right panel), \( b_{ST} + c_{ST} = 1 \) and \( b_{OS} + c_{OS} = 1 \) (dashed lines in right panel), and thereby \( a = 2 \), \( b+c=2 \), \( \beta_{WN} = 1/3 \). Fründ (2021) measured \( \beta_{OS}=\beta_{ST}=1/6 \) and argued that it is appropriate insofar as it reflects that the number of unique links in the OS and ST components contributing to network dissimilarity (dashed lines) are actually equal. Conversely, the formula of Poisot et al. (2012) yields \( \beta_{OS}=1/5 \), hence \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{5}=\frac{2}{15}<\beta_{OS} \). Fründ (2021) thus argued that the method of Poisot tends to underestimate the contribution of species turnover. To clarify and avoid misinterpretation of the calculation of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) in Poisot et al. (2012), Poisot (2022) provides a new, in-depth mathematical analysis of the decomposition of \( \beta_{WN} \). Poisot et al. (2012) quantify in \( \beta_{OS} \) the actual contribution of rewiring in network structure for the subweb of common species. Poisot (2022) thus argues that \( \beta_{OS} \) relates only to the probability of rewiring in the subweb, while the definition of \( \beta_{OS} \) by Fründ (2021) is relative to the count of interactions in the global network (considered in denominator), and is thereby dependent on both rewiring probability and species turnover. Poisot (2022) further clarifies the interpretation of \( \beta_{ST} \). \( \beta_{ST} \) is obtained by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and thus represents the influence of species turnover in terms of the relative architectures of the global networks and of the subwebs of shared species. Coming back to the example of Fig.1., the Poisot et al. (2012) formula posits that \( \frac{\beta_{ST}}{\beta_{WN}}=\frac{2/15}{1/3}=2/5 \), meaning that species turnover contributes two-fifths of change in network structure, while rewiring in the subweb of common species contributed three fifths. Conversely, the approach of Fründ (2021) does not compare the architectures of global networks and of the subwebs of shared species, but considers the relative contribution of unique links to network dissimilarity in terms of species turnover and rewiring. Poisot (2022) concludes that the partition proposed in Fründ (2021) does not allow unambiguous ecological interpretation of rewiring. He provides guidelines for proper interpretation of the decomposition proposed in Poisot et al. (2012). References Fründ J (2021) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: how to partition rewiring and species turnover components. Ecosphere, 12, e03653. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3653 Poisot T, Canard E, Mouillot D, Mouquet N, Gravel D (2012) The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecology Letters, 15, 1353–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12002 Poisot T (2022) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring. EcoEvoRxiv Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2 | Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring | Timothée Poisot | <p style="text-align: justify;">Despite having established its usefulness in the last ten years, the decomposition of ecological networks in components allowing to measure their β-diversity retains some methodological ambiguities. Notably, how to ... |  | Biodiversity, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2021-07-31 00:18:41 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle