Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * ▲ | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16 Jun 2023

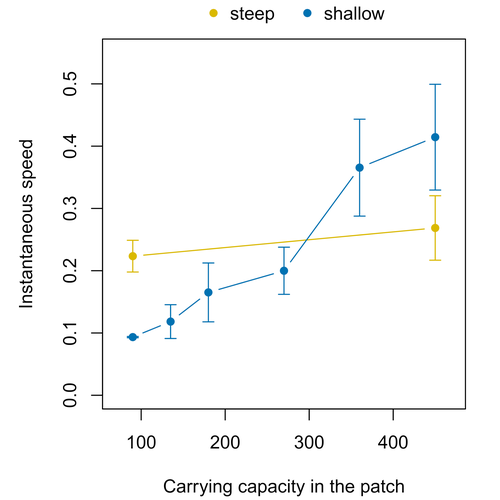

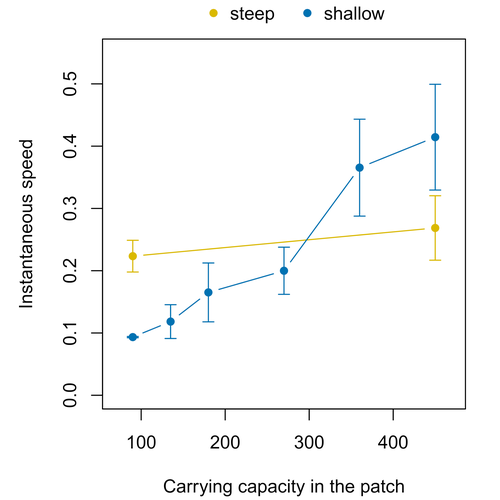

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansionThibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environmentsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Dispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007). Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients). Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011). The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions. REFERENCES Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746 Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1 Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431. Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255 Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107 Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x | Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion | Thibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken | <p>Demographic processes that occur at the local level, such as positive density dependence in growth or dispersal, are known to shape population range expansion, notably by linking carrying capacity to invasion speed. As a result of these process... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Joaquín Hortal | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-11-16 15:52:08 | View |

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View | ||

04 Sep 2019

Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora coralsK. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza https://doi.org/10.1101/398602Transcriptomics of thermal stress response in coralsRecommended by Staffan Jacob based on reviews by Mar SobralClimate change presents a challenge to many life forms and the resulting loss of biodiversity will critically depend on the ability of organisms to timely respond to a changing environment. Shifts in ecological parameters have repeatedly been attributed to global warming, with the effectiveness of these responses varying among species [1, 2]. Organisms do not only have to face a global increase in mean temperatures, but a complex interplay with another crucial but largely understudied aspect of climate change: thermal fluctuations. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adaptation to thermal fluctuations is thus a timely and critical challenge. References [1] Parmesan, C., & Yohe, G. (2003). A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature, 421(6918), 37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286 | Gene expression plasticity and frontloading promote thermotolerance in Pocillopora corals | K. Brener-Raffalli, J. Vidal-Dupiol, M. Adjeroud, O. Rey, P. Romans, F. Bonhomme, M. Pratlong, A. Haguenauer, R. Pillot, L. Feuillassier, M. Claereboudt, H. Magalon, P. Gélin, P. Pontarotti, D. Aurelle, G. Mitta, E. Toulza | <p>Ecosystems worldwide are suffering from climate change. Coral reef ecosystems are globally threatened by increasing sea surface temperatures. However, gene expression plasticity provides the potential for organisms to respond rapidly and effect... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Symbiosis | Staffan Jacob | 2018-08-29 10:46:55 | View | |

19 Mar 2024

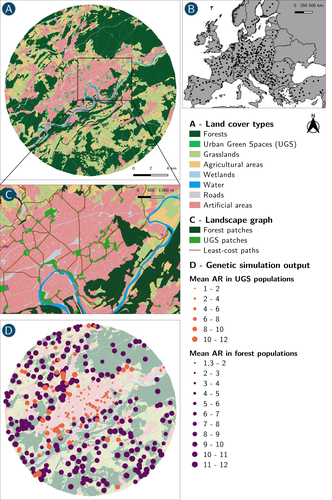

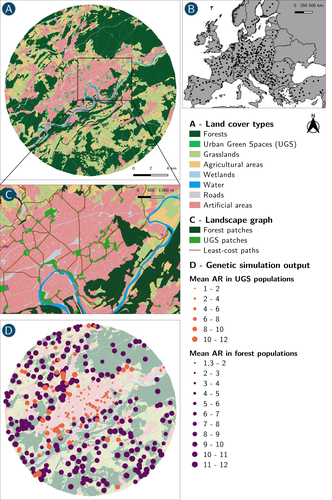

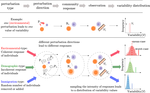

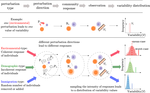

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View | |

01 Apr 2019

The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patternsJean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman https://doi.org/10.1101/431296Diversity-Stability and the Structure of PerturbationsRecommended by Kevin Cazelles and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer

In his 1972 paper “Will a Large Complex System Be Stable?” [1], May challenges the idea that large communities are more stable than small ones. This was the beginning of a fundamental debate that still structures an entire research area in ecology: the diversity-stability debate [2]. The most salient strength of May’s work was to use a mathematical argument to refute an idea based on the observations that simple communities are less stable than large ones. Using the formalism of dynamical systems and a major results on the distribution of the eigen values for random matrices, May demonstrated that the addition of random interactions destabilizes ecological communities and thus, rich communities with a higher number of interactions should be less stable. But May also noted that his mathematical argument holds true only if ecological interactions are randomly distributed and thus concluded that this must not be true! This is how the contradiction between mathematics and empirical observations led to new developments in the study of ecological networks. References [1] May, Robert M (1972). Will a Large Complex System Be Stable? Nature 238, 413–414. doi: 10.1038/238413a0 | The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patterns | Jean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman | <p>Empirical knowledge of ecosystem stability and diversity-stability relationships is mostly based on the analysis of temporal variability of population and ecosystem properties. Variability, however, often depends on external factors that act as... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Kevin Cazelles | 2018-10-02 14:01:03 | View | |

05 Feb 2020

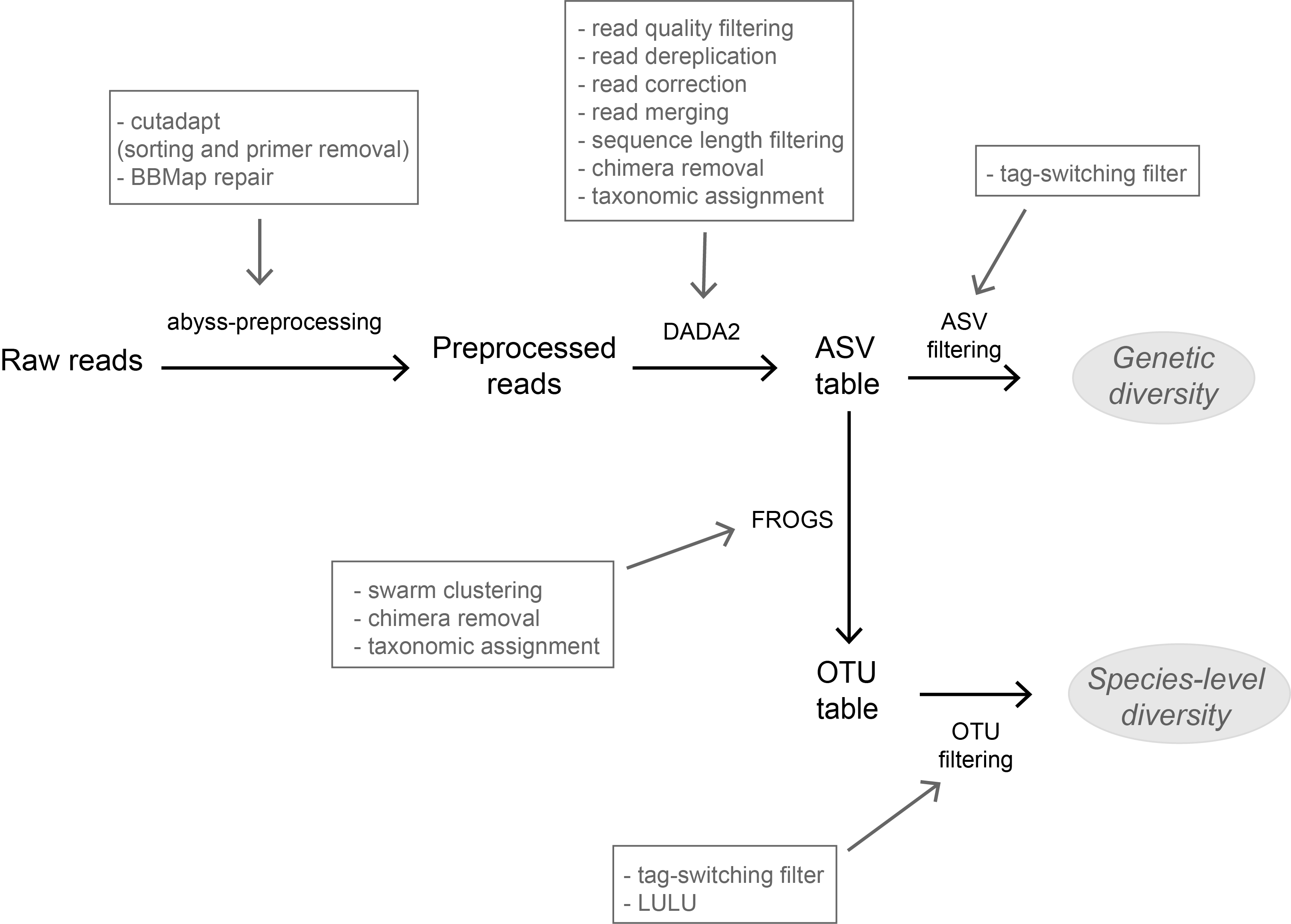

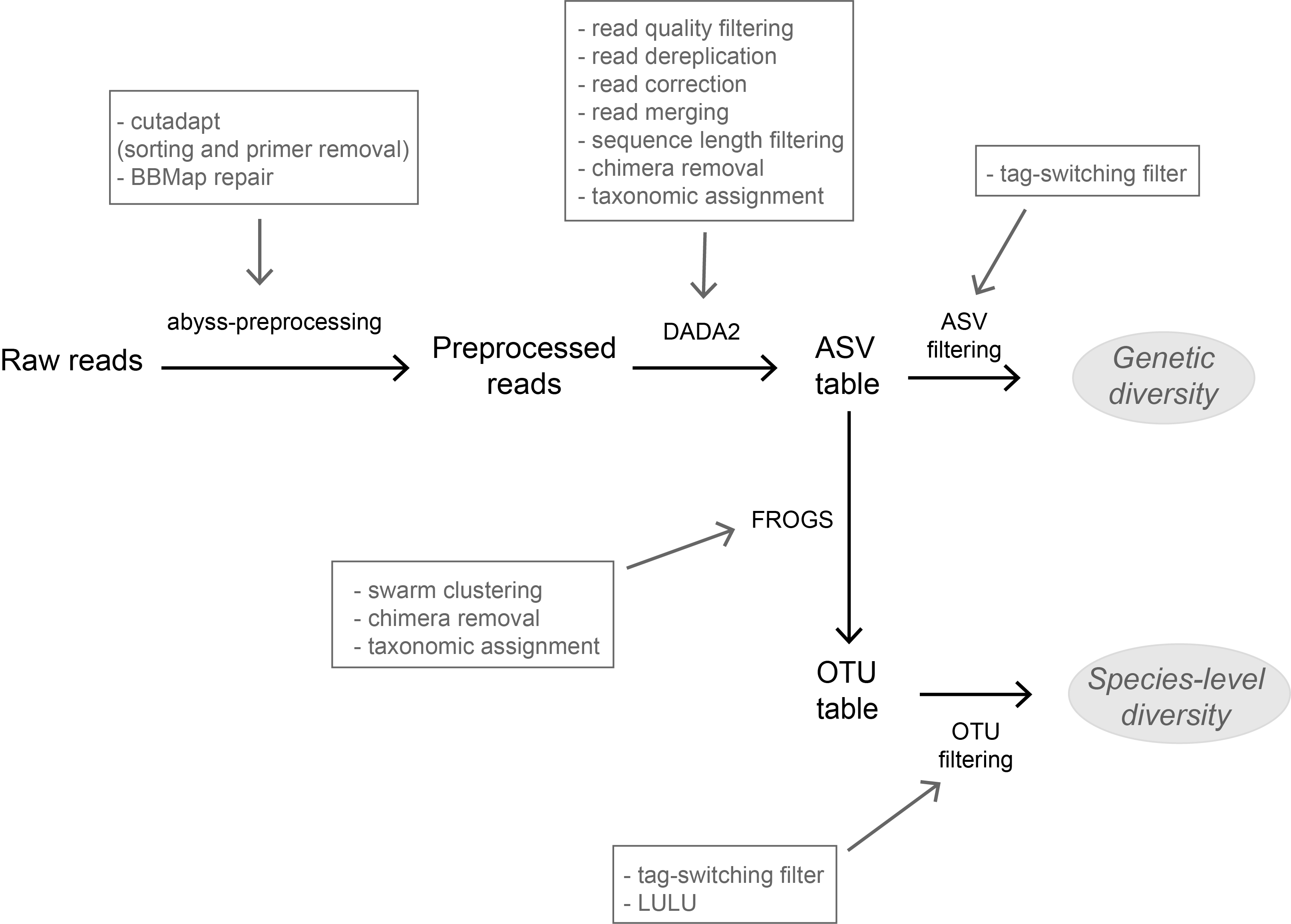

A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingMiriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://doi.org/10.1101/717355A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer

High-throughput sequencing-based techniques such as DNA metabarcoding are increasingly advocated as providing numerous benefits over morphology‐based identifications for biodiversity inventories and ecosystem biomonitoring [1]. These benefits are particularly apparent for highly-diversified and/or hardly accessible aquatic and marine environments, where simple water or sediment samples could already produce acceptably accurate biodiversity estimates based on the environmental DNA present in the samples [2,3]. However, sequence-based characterization of biodiversity comes with its own challenges. A major one resides in the capacity to disentangle true biological diversity (be it taxonomic or genetic) from artefactual diversity generated by sequence-errors accumulation during PCR and sequencing processes, or from the amplification of non-target genes (i.e. pseudo-genes). On one hand, the stringent elimination of sequence variants might lead to biodiversity underestimation through the removal of true species, or the clustering of closely-related ones. On the other hand, a more permissive sequence filtering bears the risks of biodiversity inflation. Recent studies have outlined an excellent methodological framework for addressing this issue by proposing bioinformatic tools that allow the amplicon-specific error-correction as alternative or as complement to the more arbitrary approach of clustering into Molecular Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) based on sequence dissimilarity [4,5]. But to date, the relevance of amplicon-specific error-correction tools has been demonstrated only for a limited set of taxonomic groups and gene markers. References [1] Porter, T. M., and Hajibabaei, M. (2018). Scaling up: A guide to high-throughput genomic approaches for biodiversity analysis. Molecular Ecology, 27(2), 313–338. doi: 10.1111/mec.14478 | A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcoding | Miriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Environmental metabarcoding is an increasingly popular tool for studying biodiversity in marine and terrestrial biomes. With sequencing costs decreasing, multiple-marker metabarcoding, spanning several branches of the tree of life, is becoming ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-08-02 20:52:45 | View | |

14 Nov 2022

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture modelsCécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bearRecommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated. Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008. Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007 Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135. Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025 Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719 | Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models | Cécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez | <p>Estimating the size of small populations of large mammals can be achieved via censuses, or complete counts, of recognizable individuals detected over a time period: minimum detected (population) size (MDS). However, as a population grows larger... |  | Conservation biology, Demography, Population ecology | Nicolas BECH | 2022-01-20 10:49:59 | View | |

06 Dec 2019

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslandsNatasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2543768The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradientRecommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure. References [1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press. | Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands | Natasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol | <p>For plant-pollinator interactions to occur, the flowering of plants and the flying period of pollinators (i.e. their phenologies) have to overlap. Yet, few models make use of this principle to predict interactions and fewer still are able to co... |  | Interaction networks, Pollination, Statistical ecology | Anna Eklöf | 2019-01-18 19:02:13 | View | |

18 Mar 2019

Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasiteAmalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2592114Limited dispersal in a vector on territorial hostsRecommended by Adele Mennerat based on reviews by Shelly Lachish and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitism requires parasites and hosts to meet and is therefore conditioned by their respective dispersal abilities. While dispersal has been studied in a number of wild vertebrates (including in relation to infection risk), we still have poor knowledge of the movements of their parasites. Yet we know that many parasites, and in particular vectors transmitting pathogens from host to host, possess the ability to move actively during at least part of their lives. References | Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasite | Amalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy | <p>Functional dispersal (between-site movement, with or without subsequent reproduction) is a key trait acting on the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of a species, with potential cascading effects on other members of the local community. ... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Epidemiology, Parasitology, Population ecology | Adele Mennerat | 2018-11-05 11:44:58 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snailKatja Leicht, Otto Seppälä https://doi.org/10.1101/449777Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snailsRecommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentisAmongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor. References [1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704 | Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail | Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä | <p>Global climate change imposes a serious threat to natural populations of many species. Estimates of the effects of climate change‐mediated environmental stresses are, however, often based only on their direct effects on organisms, and neglect t... |  | Climate change | vincent calcagno | 2018-10-22 22:19:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle