Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

10 Jan 2024

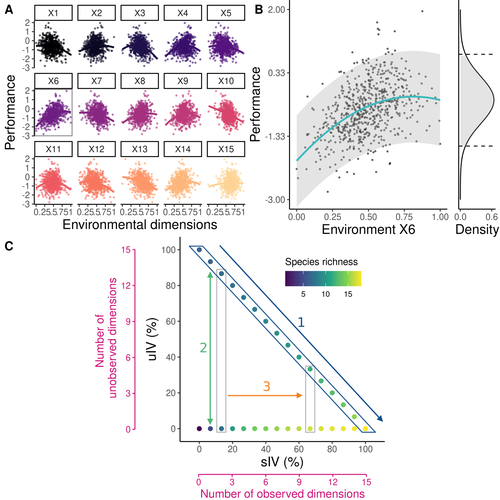

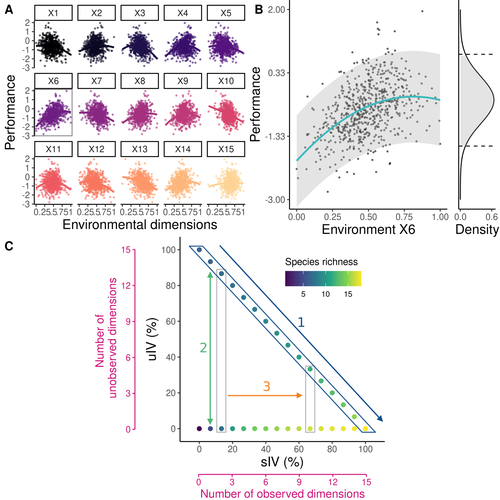

Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structureCamille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032Two paradigms for intraspecific variabilityRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and Bart Haegeman

Community ecology usually concerns itself with understanding the causes and consequences of diversity at a given taxonomic resolution, most classically at the species level. Yet there is no doubt that diversity exists at all scales, and phenotypic variability within a taxon can be comparable to differences between taxa, as observed from bacteria to fish and trees. The question that motivates an active and growing body of work (e.g. Raffard et al 2019) is not so much whether intraspecific variability matters, but what we get wrong by ignoring it and how to incorporate it into our understanding of communities. There is no established way to think about diversity at multiple nested taxonomic levels, and it is tempting to summarize intraspecific variability simply by measuring species mean and variance in any trait and metric. In this study, Girard-Tercieux et al (2023a) propose that, to understand its impact on community-level outcomes and in particular on species coexistence, we should carefully distinguish between two ways of thinking about intraspecific variability: -"unstructured" variation, where every individual's features are like an independent random draw from a species-specific distribution, for instance, due to genetic lottery and developmental accidents -"structured" variation that is due to each individual encountering a different but enduring microenvironment. The latter type of variability may still appear complex and random-like when the environment is high-dimensional (i.e. multifaceted, with many different factors contributing to each individual's performance and development). Thus, it is not necessarily "structured" in the sense of being easily understood -- we may need to measure more aspects of the environment than is practical if we want to fully predict these variations. What distinguishes this "structured" variability is that it is, in a loose sense, inheritable: individuals from the same species that grow in the same microenvironment will have the same performance, in a repeatable fashion. Thus, if each species is best at exploiting at least a fraction of environmental conditions, it is likely to avoid extinction by competition, except in the unlucky case of no propagule reaching any of the favorable sites. The core intuition, that the complex spatial structure and high-dimensional nature of the environment plays a key explanatory role in species coexistence, is a running thread through several of the authors' work (e.g. Clark et al 2010), clearly inspired by their focus on tropical forests. This study, by tackling the question of intraspecific determinants of interspecific outcomes, makes a compelling addition to this line of investigation, coming as a theoretical companion to a more data-oriented study (Girard-Tercieux et al 2023b). But I believe it raises a question that is even broader in scope. This kind of intraspecific variability, due to different individuals growing in different microenvironments, is perhaps most relevant for trees and other sessile organisms, but the distinction made here between "unstructured" and "structured" variability can likely be extended to many other ecological settings. In my understanding, what matters most in "structured" variability is not so much it stemming from a fixed environment, but rather it being maintained across generations, rather than possibly lost by drift. This difference between variability in the form of "frozen" randomness and in the form of stochastic drift over time is highly relevant in other theoretical fields (e.g. in physics, where it is the difference between a disordered solid and a liquid), and thus, I expect that it is a meaningful distinction to make throughout community ecology. References James S. Clark, David Bell, Chengjin Chu, Benoit Courbaud, Michael Dietze, Michelle Hersh, Janneke HilleRisLambers et al. (2010) "High‐dimensional coexistence based on individual variation: a synthesis of evidence." Ecological Monographs 80, no. 4 : 569-608. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1541.1 Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux (2023a) "Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure." bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.06.503032 Camille Girard‐Tercieux, Isabelle Maréchaux, Adam T. Clark, James S. Clark, Benoît Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Joannès Guillemot et al. (2023b) "Rethinking the nature of intraspecific variability and its consequences on species coexistence." Ecology and Evolution 13, no. 3 : e9860. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9860 Allan Raffard, Frédéric Santoul, Julien Cucherousset, and Simon Blanchet. (2019) "The community and ecosystem consequences of intraspecific diversity: A meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 94, no. 2: 648-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12472 | Beyond variance: simple random distributions are not a good proxy for intraspecific variability in systems with environmental structure | Camille Girard-Tercieux, Ghislain Vieilledent, Adam Clark, James S. Clark, Benoit Courbaud, Claire Fortunel, Georges Kunstler, Raphaël Pélissier, Nadja Rüger, Isabelle Maréchaux | <p>The role of intraspecific variability (IV) in shaping community dynamics and species coexistence has been intensively discussed over the past decade and modelling studies have played an important role in that respect. However, these studies oft... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2022-08-07 12:51:30 | View | |

19 Aug 2020

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metricsF. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux https://doi.org/10.1101/640995Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systemsRecommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersConservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4]. References [1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton. | Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View | |

16 Sep 2019

Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA samplingMarie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/385120Words matter: extensive misapplication of "non-invasive" in describing DNA sampling methods, and proposed clarifying termsRecommended by Thomas Wilson Sappington based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe ability to successfully sequence trace quantities of environmental DNA (eDNA) has provided unprecedented opportunities to use genetic analyses to elucidate animal ecology, behavior, and population structure without affecting the behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal sampled. Hair associated with an animal track in the snow, the shed exoskeleton of an insect, or a swab of animal scat are all examples of non-invasive methods to collect eDNA. Despite the seemingly uncomplicated definition of "non-invasive" as proposed by Taberlet et al. [1], Lefort et al. [2] highlight that its appropriate application to sampling methods in practice is not so straightforward. For example, collecting scat left behind on the forest floor by a mammal could be invasive if feces is used by that species to mark territorial boundaries. Other collection strategies such as baited DNA traps to collect hair, capturing and handling an individual to swab or stimulate emission of a body fluid, or removal of a presumed non essential body part like a feather, fish scale, or even a leg from an insect are often described as "non-invasive" sampling methods. However, such methods cannot be considered truly non-invasive. At a minimum, attracting or capturing and handling an animal to obtain a DNA sample interrupts its normal behavioral routine, but additionally can cause both acute and long-lasting physiological and behavioral stress responses and other effects. Even invertebrates exhibit long-term hypersensitization after an injury, which manifests as heightened vigilance and enhanced escape responses [3-5]. References [1] Taberlet P., Waits L. P. and Luikart G. 1999. Noninvasive genetic sampling: look before you leap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 323-327. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01637-7 | Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling | Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer | <p>The use of DNA data is ubiquitous across animal sciences. DNA may be obtained from an organism for a myriad of reasons including identification and distinction between cryptic species, sex identification, comparisons of different morphocryptic ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Molecular ecology, Zoology | Thomas Wilson Sappington | 2018-11-30 13:33:31 | View | |

03 Feb 2023

The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pairJeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879peDrivers of range expansion in a pair of sister grackle speciesRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The spatial distribution of a species is driven by both biotic and abiotic factors that may change over time (Soberón & Nakamura, 2009; Paquette & Hargreaves, 2021). Therefore, species ranges are dynamic, especially in humanized landscapes where changes occur at high speeds (Sirén & Morelli, 2020). The distribution of many species is being reduced because of human impacts; however, some species are expanding their distributions, even over their niche (Lustenhouwer & Parker, 2022). One of the factors that may lead to a geographic niche expansion is behavioral flexibility (Mikhalevich et al., 2017), but the mechanisms determining range expansion through behavioral changes are not fully understood. The PCI Ecology study by Summers et al. (2023) uses a very large database on the current and historic distribution of two species of grackles that have shown different trends in their distribution. The great-tailed grackle has largely expanded its range over the 20th century, while the range of the boat-tailed grackle has remained very similar. They take advantage of this differential response in the distribution of the two species and run several analyses to test whether it was a change in habitat availability, in the realized niche, in habitat connectivity or in in the other traits or conditions that previously limited the species range, what is driving the observed distribution of the species. The study finds a change in the niche of great-tailed grackle, consistent with the high behavioral flexibility of the species. The two reviewers and I have seen a lot of value in this study because 1) it addresses a very timely question, especially in the current changing world; 2) it is a first step to better understanding if behavioral attributes may affect species’ ability to change their niche; 3) it contrasts the results using several complementary statistical analyses, reinforcing their conclusions; 4) it is based on the preregistration Logan et al (2021), and any deviations from it are carefully explained and justified in the text and 5) the limitations of the study have been carefully discussed. It remains to know if the boat-tailed grackle has more limited behavioral flexibility than the great-tailed grackle, further confirming the results of this study. Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D (2021) Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html Lustenhouwer N, Parker IM (2022) Beyond tracking climate: Niche shifts during native range expansion and their implications for novel invasions. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14395 Mikhalevich I, Powell R, Logan C (2017) Is behavioural flexibility evidence of cognitive complexity? How evolution can inform comparative cognition. Interface Focus, 7, 20160121. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121 Paquette A, Hargreaves AL (2021) Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters, 24, 2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864 Sirén APK, Morelli TL (2020) Interactive range-limit theory (iRLT): An extension for predicting range shifts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89, 940–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13150 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Summers JT, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2022) The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe | The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair | Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen | <p>---This is a POST-STUDY manuscript for the PREREGISTRATION, which received in principle acceptance in 2020 from Dr. Sebastián González (reviewed by Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow; <a href="https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ec... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biogeography, Dispersal & Migration, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Preregistrations, Species distributions | Esther Sebastián González | 2022-05-26 20:07:33 | View | |

20 Sep 2018

When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagationMarjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques https://doi.org/10.1101/307322When the dispersal of the many outruns the dispersal of the fewRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

Are biological invasions driven by a few pioneers, running ahead of their conspecifics? Or are these pioneers constantly being caught up by, and folded into, the larger flux of propagules from the established populations behind them? References [1] Levins, R., & Culver, D. (1971). Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68(6), 1246–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246 | When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation | Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100004). Finding general patterns in the expansion of natural populations is a major challenge in ecology and invasion biology... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | Yuval Zelnik | 2018-04-25 10:18:48 | View |

23 Mar 2020

Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascadesArnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne https://doi.org/10.1101/722140Tell me what you’ve eaten, I’ll tell you how much you’ll eat (and be eaten)Recommended by Sara Magalhães and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 1 anonymous reviewerTritrophic interactions have a central role in ecological theory and applications [1-3]. Particularly, systems comprised of plants, herbivores and predators have historically received wide attention given their ubiquity and economic importance [4]. Although ecologists have long aimed to understand the forces that govern alternating ecological effects at successive trophic levels [5], several key open questions remain (at least partially) unanswered [6]. In particular, the analysis of complex food webs has questioned whether ecosystems can be viewed as a series of trophic chains [7,8]. Moreover, whether systems are mostly controlled by top-down (trophic cascades) or bottom-up processes remains an open question [6]. References [1] Price, P. W., Bouton, C. E., Gross, P., McPheron, B. A., Thompson, J. N., & Weis, A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 11(1), 41-65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353 | Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades | Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne | <p>Trophic cascades, the indirect effect of predators on non-adjacent lower trophic levels, are important drivers of the structure and dynamics of ecological communities. However, the influence of intraspecific trait variation on the strength of t... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Food webs, Population ecology | Sara Magalhães | 2019-08-02 09:11:03 | View | |

03 Jan 2024

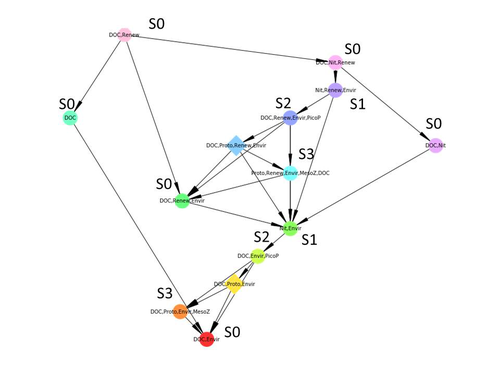

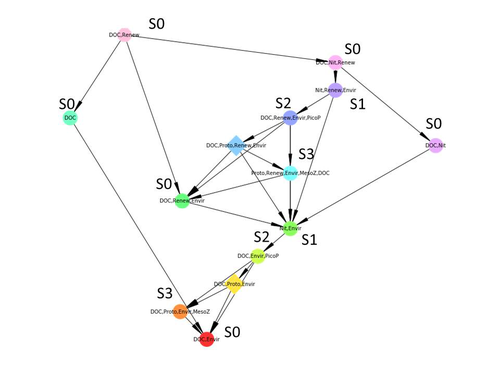

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changesCedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networksRecommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewerModelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks. Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model. The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed. The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics. Reference Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055 | Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes | Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy | <p>Trophic interaction networks are notoriously difficult to understand and to diagnose (i.e., to identify contrasted network functioning regimes). Such ecological networks have many direct and indirect connections between species, and these conne... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Interaction networks, Microbial ecology & microbiology | Francis Raoul | Tim Coulson | 2023-07-03 10:42:34 | View |

21 Oct 2020

Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate changeJames Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.26.117200Uncertain predictions of species responses to perturbations lead to underestimate changes at ecosystem level in diverse systemsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by Carlos Melian and 1 anonymous reviewerDifferent sources of uncertainty are known to affect our ability to predict ecological dynamics (Petchey et al. 2015). However, the consequences of uncertainty on prediction biases have been less investigated, especially when predictions are scaled up to higher levels of organisation as is commonly done in ecology for instance. The study of Orr et al. (2020) addresses this issue. It shows that, in complex systems, the uncertainty of unbiased predictions at a lower level of organisation (e.g. species level) leads to a bias towards underestimation of change at higher level of organisation (e.g. ecosystem level). This bias is strengthened by larger uncertainty and by higher dimensionality of the system. References Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, Kinzig AP, Daily GC, Loreau M, Grace JB, Larigauderie A, Srivastava DS, Naeem S (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148 | Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate change | James Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi | <p>Uncertainty is an irreducible part of predictive science, causing us to over- or underestimate the magnitude of change that a system of interest will face. In a reductionist approach, we may use predictions at the level of individual system com... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Theoretical ecology | Elisa Thebault | Anonymous | 2020-06-02 15:41:12 | View |

19 Dec 2020

Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.)Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.986984A new member of the morphometrics jungle to better monitor vulnerable lagoonsRecommended by Vincent Bonhomme based on reviews by Julien Claude and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the recent years, morphometrics, the quantitative description of shape and its covariation [1] gained considerable momentum in evolutionary ecology. Using the form of organisms to describe, classify and try to understand their diversity can be traced back at least to Aristotle. More recently, two successive revolutions rejuvenated this idea [1–3]: first, a proper mathematical refoundation of the theory of shape, then a technical revolution in the apparatus able to acquire raw data. By using a feature extraction method and planning its massive use on data acquired by aerial drones, the study by Lacaux and colleagues [4] retraces this curse of events. The sample sizes studied here were too low to allow finer-grained ecophysiological investigations. That being said, the proof-of-concept is convincing and this paper paths the way for an operational and innovative approach to the ecological monitoring of sensible aquatic ecosystems. References [1] Kendall, D. G. (1989). A survey of the statistical theory of shape. Statistical Science, 87-99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177012589 | Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) | Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry | <p>Variations of the animal body plan morphology and morphometry can be used as prognostic tools of their habitat quality. The potential of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) as a new model organism has been poorly tested. However, as a tetramerous... |  | Morphometrics | Vincent Bonhomme | 2020-03-18 17:40:51 | View | |

28 Dec 2022

Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouseCharlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512An experimental approach for understanding how terrestrial isopods respond to environmental stressorsRecommended by Aniruddha Belsare based on reviews by Aaron Yilmaz and Michael MorrisIn this article, the authors discuss the results of their study investigating the effects of heat stress and moisture stress on a terrestrial isopod Armadilldium vulgare, the common woodlouse [1]. Specifically, the authors have assessed how increased temperature or decreased moisture affects life history traits (such as growth, survival, and reproduction) as well as physiological traits (immune cell parameters and \( beta \)-galactosidase activity). This article quantitatively evaluates the effects of the two stressors on woodlouse. Terrestrial isopods like woodlouse are sensitive to thermal and moisture stress [2; 3] and are therefore good models to test hypotheses in global change biology and for monitoring ecosystem health. An important feature of this study is the combination of experimental, laboratory, and analytical techniques. Experiments were conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory by modulating temperature and moisture, life history and physiological traits were measured/analyzed and then tested using models. Both stressors had negative impacts on survival and reproduction of woodlouse, and result in premature ageing. Although thermal stress did not affect survival, it slowed woodlouse growth. Moisture stress did not have a detectable effect on woodlouse growth but decreased survival and reproductive success. An important insight from this study is that effects of heat and moisture stressors on woodlouse are not necessarily linear, and experimental approaches can be used to better elucidate the mechanisms and understand how these organisms respond to environmental stress. This article is timely given the increasing attention on biological monitoring and ecosystem health. References: [1] Depeux C, Branger A, Moulignier T, Moreau J, Lemaître J-F, Dechaume-Moncharmont F-X, Laverre T, Pauhlac H, Gaillard J-M, Beltran-Bech S (2022) Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse. bioRxiv, 2022.09.26.509512., ver. 3 peer-reviewd and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512 [2] Warburg MR, Linsenmair KE, Bercovitz K (1984) The effect of climate on the distribution and abundance of isopods. In: Sutton SL, Holdich DM, editors. The Biology of Terrestrial Isopods. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 339–367. [3] Hassall M, Helden A, Goldson A, Grant A (2005) Ecotypic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity in reproductive traits of Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda: Oniscidea). Oecologia 143: 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1772-3 | Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse | Charlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech | <p>We tested independently the influences of increasing temperature and decreasing moisture on life history and physiological traits in the arthropod <em>Armadillidium vulgare</em>. Both increasing temperature and decreasing moisture led individua... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Life history, Physiology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Aniruddha Belsare | 2022-09-28 13:13:47 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle