Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

23 Oct 2023

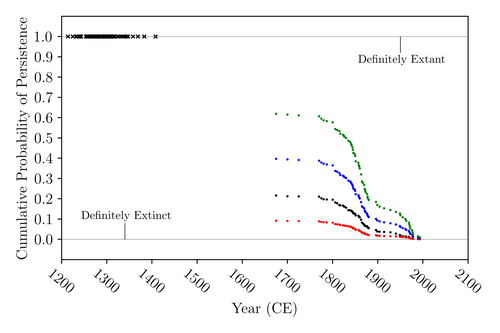

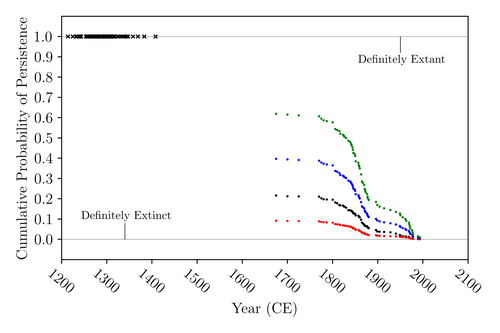

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

06 Mar 2020

The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategiesCharlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux https://doi.org/10.1101/790634The importance of spatio-temporal dynamics on MPA's designRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Ana S. L. Rodrigues and 1 anonymous reviewerMarine protected areas (MPA) have arisen as the main approach for conservation of marine species. Fishes, marine mammals and birds can be conservation targets that justify the implementation of these areas. However, MPAs undergo many of the problems faced by their terrestrial equivalent. One of the major concerns is that these conservation areas are spatially constrained, by logistic reasons, and many times these constraints caused that key areas for the species (reproductive sites, refugees, migration) fall outside the limits, making conservation efforts even more difficult. Lambert et al. [1] evaluate at what point the Bay of Biscay MPA contains key ecological areas for several emblematic species. The evaluation incorporated a spatio-temporal dimension. To evaluate these ideas, authors evaluate two population descriptors: aggregation and persistence of several species of cetaceans and seabirds. References [1] Lambert, C., Dorémus, G. and V. Ridoux (2020) The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies. bioRxiv, 790634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/790634 | The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies | Charlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux | <p>The main type of zonal conservation approaches corresponds to Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are spatially defined and generally static entities aiming at the protection of some target populations by the implementation of a management pla... |  | Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Species distributions | Sergio Estay | 2019-10-03 08:47:17 | View | |

02 Dec 2021

Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289The promise and limits of DNA based approach to infer diet flexibility in endangered top predatorsRecommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond based on reviews by Francis John Burdon and Babett GüntherThere is growing evidence of worldwide decline of populations of top predators, including marine ones (Heithaus et al, 2008, Mc Cauley et al., 2015), with cascading effects expected at the ecosystem level, due to global change and human activities, including habitat loss or fragmentation, the collapse or the range shifts of their preys. On a global scale, seabirds are among the most threatened group of birds, about one-third of them being considered as threatened or endangered (Votier& Sherley, 2017). The large consequences of the decrease of the populations of preys they feed on (Cury et al, 2011) points diet flexibility as one important element to understand for effective management (McInnes et al, 2017). Nevertheless, morphological inventory of preys requires intrusive protocols, and the differential digestion rate of distinct taxa may lead to a large bias in morphological-based diet assessments. The use of DNA metabarcoding on feces (or diet DNA, dDNA) now allows non-invasive approaches facilitating the recollection of samples and the detection of multiple preys independently of their digestion rates (Deagle et al., 2019). Although no gold standard exists yet to avoid bias associated with metabarcoding (primer bias, gaps in reference databases, inability to differentiate primary from secondary predation…), the use of these recent techniques has already improved the knowledge of the foraging behaviour and diet of many animals (Ando et al., 2020). Both promise and shortcomings of this approach are illustrated in the article “Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)” by Quereteja et al. (2021). In this work, the authors assessed the nature and spatio-temporal flexibility of the foraging behaviour and consequent diet of the endangered petrel Procellaria westlandica from New-Zealand through metabarcoding of faeces samples. The results of this dDNA, non-invasive approach, identify some expected and also unexpected prey items, some of which require further investigation likely due to large gaps in the reference databases. They also reveal the temporal (before and after hatching) and spatial (across colonies only 1.5km apart) flexibility of the foraging behaviour, additionally suggesting a possible influence of fisheries activities in the surroundings of the colonies. This study thus both underlines the power of the non-invasive metabarcoding approach on faeces, and the important results such analysis can deliver for conservation, pointing a potential for diet flexibility that may be essential for the resilience of this iconic yet endangered species. References Ando H, Mukai H, Komura T, Dewi T, Ando M, Isagi Y (2020) Methodological trends and perspectives of animal dietary studies by noninvasive fecal DNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 2, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.117 Cury PM, Boyd IL, Bonhommeau S, Anker-Nilssen T, Crawford RJM, Furness RW, Mills JA, Murphy EJ, Österblom H, Paleczny M, Piatt JF, Roux J-P, Shannon L, Sydeman WJ (2011) Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion—One-Third for the Birds. Science, 334, 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212928 Deagle BE, Thomas AC, McInnes JC, Clarke LJ, Vesterinen EJ, Clare EL, Kartzinel TR, Eveson JP (2019) Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 28, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14734 Heithaus MR, Frid A, Wirsing AJ, Worm B (2008) Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.003 McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347, 1255641. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641 McInnes JC, Jarman SN, Lea M-A, Raymond B, Deagle BE, Phillips RA, Catry P, Stanworth A, Weimerskirch H, Kusch A, Gras M, Cherel Y, Maschette D, Alderman R (2017) DNA Metabarcoding as a Marine Conservation and Management Tool: A Circumpolar Examination of Fishery Discards in the Diet of Threatened Albatrosses. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00277 Querejeta M, Lefort M-C, Bretagnolle V, Boyer S (2021) Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). bioRxiv, 2020.10.30.360289, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289 Votier SC, Sherley RB (2017) Seabirds. Current Biology, 27, R448–R450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.042 | Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica) | Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer | <p style="text-align: justify;">As top predators, seabirds can be indirectly impacted by climate variability and commercial fishing activities through changes in marine communities. However, high mobility and foraging behaviour enables seabirds to... |  | Conservation biology, Food webs, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Sophie Arnaud-Haond | 2020-10-30 20:14:50 | View | |

14 Nov 2022

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture modelsCécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bearRecommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated. Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008. Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007 Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135. Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025 Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719 | Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models | Cécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez | <p>Estimating the size of small populations of large mammals can be achieved via censuses, or complete counts, of recognizable individuals detected over a time period: minimum detected (population) size (MDS). However, as a population grows larger... |  | Conservation biology, Demography, Population ecology | Nicolas BECH | 2022-01-20 10:49:59 | View | |

14 May 2019

Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imagingMarie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches https://doi.org/10.1101/425561OB-GYN for salmon parrsRecommended by Jean-Olivier Irisson based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population dynamics and stock assessment models are only as good as the data used to parameterise them. For Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations, a critical parameter may be frequency of precocious maturation. Indeed, the young males (parrs) that mature early, before leaving the river to reach the ocean, can contribute to reproduction but have much lower survival rates afterwards. The authors cite evidence of the potentially major consequences of this alternate reproductive strategy. So, to be parameterised correctly, it needs to be assessed correctly. Cue the ultrasound machine. Through a thorough analysis of data collected on 850 individuals [1], over three years, the authors clearly show that the non-invasive examination of the internal cavity of young fishes to look for gonads, using a portable ultrasound machine, provides reliable and replicable evidence of precocious maturation. They turned into OB-GYN for salmons (albeit for male salmons!) and it worked. While using ultrasounds to detect fish gonads is not a new idea (early attempts for salmonids date back to the 80s [2]), the value here is in the comparison with the classic visual inspection technique (which turns out to be less reliable) and the fact that ultrasounds can now easily be carried out in the field. Beyond the potentially important consequences of this new technique for the correct assessment of salmon population dynamics, the authors also make the case for the acquisition of more reliable individual-level data in ecological studies, which I applaud. References. [1] Nevoux M, Marchand F, Forget G, Huteau D, Tremblay J, and Destouches J-P. (2019). Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging. bioRxiv 425561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/425561 | Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging | Marie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches | <p>Salmonids are characterized by a large diversity of life histories, but their study is often limited by the imperfect observation of the true state of an individual in the wild. Challenged by the need to reduce uncertainty of empirical data, re... | Conservation biology, Demography, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Jean-Olivier Irisson | 2018-09-25 17:24:59 | View | ||

09 Nov 2023

Mark loss can strongly bias estimates of demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasetsFrédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485763Marks lost in action, biased estimationsRecommended by Sylvain Billiard based on reviews by Olivier Gimenez, Devin Johnson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Olivier Gimenez, Devin Johnson and 1 anonymous reviewer

Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) data are commonly used to estimate ecological variables such as abundance, survival probability, or transition rates from one state to another (e.g. from juvenile to adult, or migration from one site to another). Many studies have shown how estimations can be affected by neglecting one aspect of the population under study (e.g. the heterogeneity in survival between individuals) or one limit of the methodology itself (e.g. the fact that observers might not detect an individual although it is still alive). Strikingly, very few studies have yet assessed the robustness of one fundamental assumption of all CMR-based inferences: marks are supposed definitive and immutable. If they are not, how are estimations affected? Addressing this issue is the main goal of the paper by Touzalin et al. (2023), and they did a very nice work. But, because the answer is not that simple, it also calls for further investigations. When and why would mark loss bias estimation? In at least two situations. First, when estimating survival rates: if an individual loses its mark, it will be considered as dead, hence death rates will be overestimated. Second, more subtly, when estimating transition rates: if one individual loses its mark at the specific moment where its state changes, then a transition will be missed in data. The history of the marked individual would then be split into two independent CMR sequences as if there were two different individuals, including one which died. Touzalin et al. (2023) thoroughly studied these two situations by estimating ecological parameters on 1) well-thought simulated datasets, that cover a large range of possible situations inspired from a nice compilation of hundreds of estimations from fish and bats studies, and 2) on their own bats dataset, for which they had various sources of information about mark losses, i.e. different mark types on the same individuals, including mark based on genotypes, and marks found on the soil in the place where bats lived. Their main findings from the simulated datasets are that there is a general trend for underestimation of survival and transition rates if mark loss is not accounting for in the model, as it would be intuitively expected. However, they also showed from the bats dataset that biases do not show any obvious general trend, suggesting complex interactions between different ecological processes and/or with the estimation procedure itself. The results by Touzalin et al. (2023) strongly suggest that mark loss should systematically be included in models estimating parameters from CMR data. In addition to adapt the inferential models, the authors also recommend considering either a double marking, or even a single but ‘permanent’ mark such as one based on the genotypes. However, the potential gain of a double marking or of the use of genotypes is still to be evaluated both in theory and practice, and it seems to be not that obvious at first sight. First because double marking can be costly for experimenters but also for the marked animals, especially as several studies showed that marks can significantly affect survival or recapture rates. Second because multiple sources of errors can affect genotyping, which would result in wrong individual assignations especially in populations with low genetic diversity or high inbreeding, or no individual assignation at all, which would increase the occurrence of missing data in CMR datasets. Touzalin et al. (2023) supposed in their paper that there were no genotyping errors, but one can doubt it to be true in most situations. They have now important and interesting other issues to address. References Frédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille (2023) Mark loss can strongly bias demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasets. BioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485763 | Mark loss can strongly bias estimates of demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasets | Frédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. The development of methods for individual identification in wild species and the refinement of Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) models over the past few decades have greatly improved the assessment of population demo... | Conservation biology, Demography | Sylvain Billiard | 2022-04-12 18:49:34 | View | ||

24 May 2022

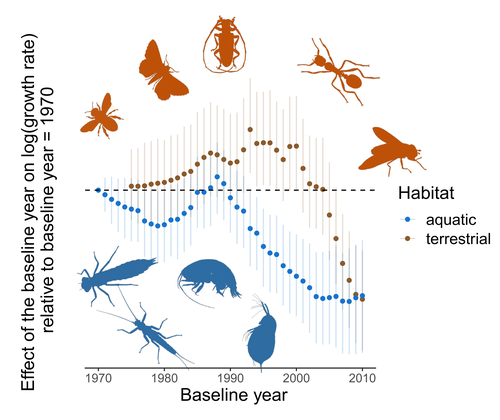

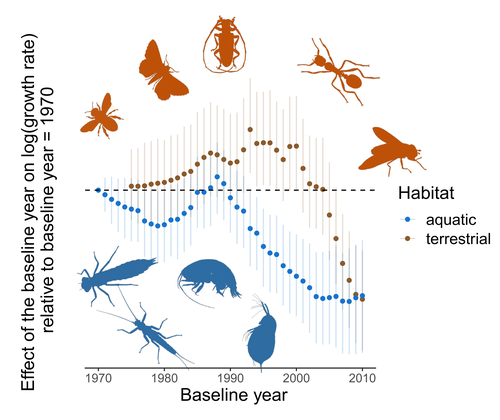

Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline?François Duchenne, Emmanuelle Porcher, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Grégoire Loïs, Colin Fontaine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.479422Don't jump to conclusions on arthropod abundance dynamics without appropriate dataRecommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Gabor L Lovei and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Gabor L Lovei and 1 anonymous reviewer

Humans are dramatically modifying many aspects of our planet via increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, patterns of land-use change, and unsustainable exploitation of the planet’s resources. These changes impact the abundance of species of wild organisms, with winners and losers. Identifying how different species and groups of species are influenced by anthropogenic activity in different biomes, continents, and habitats, has become a pressing scientific question with many publications reporting analyses of disparate data on species population sizes. Many conclusions are based on the linear analysis of rather short time series of organismal abundances. Duchenne F, Porcher E, Mihoub J-B, Loïs G, Fontaine C (2022) Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? bioRxiv, 2022.02.09.479422, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.479422 | Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? | François Duchenne, Emmanuelle Porcher, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Grégoire Loïs, Colin Fontaine | <p style="text-align: justify;">Recently, a number of studies have reported somewhat contradictory patterns of temporal trends in arthropod abundance, from decline to increase. Arthropods often exhibit non-monotonous variation in abundance over ti... |  | Conservation biology | Tim Coulson | 2022-02-11 15:44:44 | View | |

22 Mar 2021

Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore speciesBastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544Plants preserve the ghost of competition past for herbivores, but mothers don’t careRecommended by Sara Magalhães based on reviews by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-PereiraSome biological hypotheses are widely popular, so much so that we tend to forget their original lack of success. This is particularly true for hypotheses with catchy names. The ‘Ghost of competition past’ is part of the title of a paper by the great ecologist, JH Connell, one of the many losses of 2020 (Connell 1980). The hypothesis states that, even though we may not detect competition in current populations, their traits and distributions may be shaped by past competition events. Although this hypothesis has known a great success in the ecological literature, the original paper actually ends with “I will no longer be persuaded by such invoking of "the Ghost of Competition Past"”. Similarly, the hypothesis that mothers of herbivores choose host plants where their offspring will have a higher fitness was proposed by John Jaenike in 1978 (Jaenike 1978), and later coined the ‘mother knows best’ hypothesis. The hypothesis was readily questioned or dismissed: “Mother doesn't know best” (Courtney and Kibota 1990), or “Does mother know best?” (Valladares and Lawton 1991), but remains widely popular. It thus seems that catchy names (and the intuitive ideas behind them) have a heuristic value that is independent from the original persuasion in these ideas and the accumulation of evidence that followed it. The paper by Castagneryol et al. (2021) analyses the preference-performance relationship in the box tree moth (BTM) Cydalima perspectalis, after defoliation of their host plant, the box tree, by conspecifics. It thus has bearings on the two previously mentioned hypotheses. Specifically, they created an artificial population of potted box trees in a greenhouse, in which 60 trees were infested with BTM third instar larvae, whereas 61 were left uninfested. One week later, these larvae were removed and another three weeks later, they released adult BTM females and recorded their host choice by counting egg clutches laid by these females on the plants. Finally, they evaluated the effect of previously infested vs uninfested plants on BTM performance by measuring the weight of third instar larvae that had emerged from those eggs. This experimental design was adopted because BTM is a multivoltine species. When the second generation of BTM arrives, plants have been defoliated by the first generation and did not fully recover. Indeed, Castagneryol et al. (2021) found that larvae that developed on previously infested plants were much smaller than those developing on uninfested plants, and the same was true for the chrysalis that emerged from those larvae. This provides unequivocal evidence for the existence of a ghost of competition past in this system. However, the existence of this ghost still does not result in a change in the distribution of BTM, precisely because mothers do not know best: they lay as many eggs on plants previously infested than on uninfested plants. The demonstration that the previous presence of a competitor affects the performance of this herbivore species confirms that ghosts exist. However, whether this entails that previous (interspecific) competition shapes species distributions, as originally meant, remains an open question. Species phenology may play an important role in exposing organisms to the ghost, as this time-lagged competition may have been often overlooked. It is also relevant to try to understand why mothers don’t care in this, and other systems. One possibility is that they will have few opportunities to effectively choose in the real world, due to limited dispersal or to all plants being previously infested. References Castagneyrol, B., Halder, I. van, Kadiri, Y., Schillé, L. and Jactel, H. (2021) Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.228544, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544 Connell, J. H. (1980). Diversity and the coevolution of competitors, or the ghost of competition past. Oikos, 131-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 Courtney, S. P. and Kibota, T. T. (1990) in Insect-plant interactions (ed. Bernays, E.A.) 285-330. Jaenike, J. (1978). On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects. Theoretical population biology, 14(3), 350-356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6 Valladares, G., and Lawton, J. H. (1991). Host-plant selection in the holly leaf-miner: does mother know best?. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 227-240. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/5456

| Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species | Bastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel | <p>Conspecific insect herbivores co-occurring on the same host plant interact both directly through interference competition and indirectly through exploitative competition, plant-mediated interactions and enemy-mediated interactions. However, the... |  | Competition, Herbivory, Zoology | Sara Magalhães | 2020-08-03 15:50:23 | View | |

08 Jan 2020

Studies of NH4+ and NO3- uptake ability of subalpine plants and resource-use strategy identified by their functional traitsLegay Nicolas, Grassein Fabrice, Arnoldi Cindy, Segura Raphaël, Laîné Philippe, Lavorel Sandra, Clément Jean-Christophe https://doi.org/10.1101/372235Nitrate or not nitrate. That is the questionRecommended by Sébastien Barot based on reviews by Vincent Maire and 1 anonymous reviewerThe article by Legay et al. [1] addresses two main issues: the links between belowground and aboveground plant traits and the links between plant strategies (as defined by these traits) and the capacity to absorb nitrate and ammonium. I recommend this work because these are important and current issues. The literature on plant traits is extremely rich and the existence of a leaf economic spectrum linked to a gradient between conservative and acquisitive plants is now extremely well established [2-3]. Many teams are now working on belowground traits and possible links with the aboveground gradients [4-5]. It seems indeed that there is a root economic spectrum but this spectrum is apparently less pronounced than the leaf economic spectrum. The existence of links between the two spectrums are still controversial and are likely not universal as suggested by discrepant results and after all a plant could have a conservative strategy aboveground and an acquisitive strategy belowground (or vice-versa) because, indeed, constraints are different belowground and aboveground (for example because in given ecosystem/vegetation type light may be abundant but not water or mineral nutrients). The various results obtained also suggest that we do not full understand the diversity of belowground strategies, what is at stake with these strategies, and the links with root characteristics. References [1] Legay, N., Grassein, F., Arnoldi, C., Segura, R., Laîné, P., Lavorel, S. and Clément, J.-C. (2020). Studies of NH4+ and NO3- uptake ability of subalpine plants and resource-use strategy identified by their functional traits. bioRxiv, 372235, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/372235 | Studies of NH4+ and NO3- uptake ability of subalpine plants and resource-use strategy identified by their functional traits | Legay Nicolas, Grassein Fabrice, Arnoldi Cindy, Segura Raphaël, Laîné Philippe, Lavorel Sandra, Clément Jean-Christophe | <p>The leaf economics spectrum (LES) is based on a suite of leaf traits related to plant functioning and ranges from resource-conservative to resource-acquisitive strategies. However, the relationships with root traits, and the associated belowgro... |  | Community ecology, Physiology, Terrestrial ecology | Sébastien Barot | 2018-07-19 14:22:28 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle