Latest recommendations

| Id▼ | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 Jul 2023

Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlandsMallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780Searching for conservation opportunities at the marginsRecommended by Ana S. L. Rodrigues based on reviews by Scott Wilson and Elena D ConcepciónIn a progressively human-dominated planet (Venter et al., 2016), the fate of many species will depend on the extent to which they can persist in anthropogenic landscapes. In Western Europe, where only small areas of primary habitat remain (e.g. Sabatini et al., 2018), semi-natural areas are crucial habitats to many native species, yet they are threatened by the expansion of human activities, including agricultural expansion and intensification (Rigal et al., 2023). A new study by Mallet and colleagues (Mallet et al., 2023) investigates the extent to which bird species in the Camargue region are able to use the margins of agricultural fields as substitutes for their preferred semi-natural habitats. Located in the delta of the Rhône River in Southern France, the Camargue is internationally recognized for its biodiversity value, classified as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO and as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention (IUCN & UN-WCMC, 2023). Mallet and colleagues tested three specific hypotheses: that grass strips (grassy field boundaries, including grassy tracks or dirt roads used for moving agricultural machinery) can function as substitute habitats for grassland species; that reed strips along drainage ditches (common in the rice paddy landscapes of the Camargue) can function as substitute habitats to wetland species; and that hedgerows can function as substitute habitats to species that favour woodland edges. They did so by measuring how the local abundances of 14 bird species (nine typical of forest edges, 3 of grasslands, and two of reedbeds) respond to increasing coverage of either the three types of field margins or of the three types of semi-natural habitat. This is an elegant study design, yet – as is often the case with real field data – results are not as simple as expected. Indeed, for most species (11 out of 14) local abundances did not increase significantly with the area of their supposed primary habitat, undermining the assumption that they are strongly associated with (or dependent on) those habitats. Among the three species that did respond positively to the area of their primary habitat, one (a forest edge species) responded positively but not significantly to the area of field margins (hedgerows), providing weak evidence to the habitat compensation hypothesis. For the other two (grassland and a wetland species), abundance responded even more strongly to the area of field margins (grass and reed strips, respectively) than to the primary habitat, suggesting that the field margins are not so much a substitute but valuable habitats in their own right. It would have been good conservation news if field margins were found to be suitable habitat substitutes to semi-natural habitats, or at least reasonable approximations, to most species. Given that these margins have functional roles in agricultural landscapes (marking boundaries, access areas, water drainage), they could constitute good win-win solutions for reconciling biodiversity conservation with agricultural production. Alas, the results are more complicated than that, with wide variation in species responses that could not have been predicted from presumed habitat affinities. These results illustrate the challenges of conservation practice in complex landscapes formed by mosaics of variable land use types. With species not necessarily falling neatly into habitat guilds, it becomes even more challenging to plan strategically how to manage landscapes to optimize their conservation. The results presented here suggest that species’ abundances may be responding to landscape variables not taken into account in the analyses, such as connectivity between habitat patches, or maybe positive and negative edge effects between land use types. That such uncertainties remain even in a well-studied region as the Camargue, and for such a well-studied taxon such as birds, only demonstrates the continued importance of rigorous field studies testing explicit hypotheses such as this one by Mallet and colleagues. References IUCN, & UN-WCMC (2023). Protected Planet. Protected Planet. https://www.protectedplanet.net/en Mallet, P., Béchet, A., Sirami, C., Mesléard, F., Blanchon, T., Calatayud, F., Dagonet, T., Gaget, E., Leray, C., & Galewski, T. (2023). Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490780, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490780 Rigal, S., Dakos, V., Alonso, H., Auniņš, A., Benkő, Z., Brotons, L., Chodkiewicz, T., Chylarecki, P., de Carli, E., del Moral, J. C. et al. (2023). Farmland practices are driving bird population decline across Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120, e2216573120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216573120 Sabatini, F. M., Burrascano, S., Keeton, W. S., Levers, C., Lindner, M., Pötzschner, F., Verkerk, P. J., Bauhus, J., Buchwald, E., Chaskovsky, O., Debaive, N. et al. (2018). Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Diversity and Distributions, 24, 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12778 Venter, O., Sanderson, E. W., Magrach, A., Allan, J. R., Beher, J., Jones, K. R., Possingham, H. P., Laurance, W. F., Wood, P., Fekete, B. M., Levy, M. A., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nature Communications, 7, 12558. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12558 | Field margins as substitute habitat for the conservation of birds in agricultural wetlands | Mallet Pierre, Béchet Arnaud, Sirami Clélia, Mesléard François, Blanchon Thomas, Calatayud François, Dagonet Thomas, Gaget Elie, Leray Carole, Galewski Thomas | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding birds in agricultural landscapes have declined considerably since the 1950s and the beginning of agricultural intensification in Europe. Given the increasing pressure on agricultural land, it is necessary t... | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Landscape ecology | Ana S. L. Rodrigues | 2022-05-09 10:48:49 | View | ||

28 Feb 2023

Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird communityAmbre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715Two common European songbirds elicit different community responses with their mobbing callsRecommended by Tim Parker based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many bird species participate in mobbing in which individuals approach a predator while producing conspicuous vocalizations (Magrath et al. 2014). Mobbing is interesting to behavioral ecologists because of the complex array of costs of benefits. Costs range from the obvious risk of approaching a predator while drawing that predator’s attention to the more mundane opportunity costs of taking time away from other activities, such as foraging. Benefits may involve driving the predator to leave, teaching relatives to recognize predators, signaling quality to conspecifics, or others. An added layer of complexity in this system comes from the inter-specific interactions that often occur among different mobbing species (Magrath et al. 2014). This study by Salis et al. (2023) explored the responses of a local bird community to mobbing calls produced by individuals of two common mobbing species in European forests, coal tits, and crested tits. Not only did they compare responses to these two different species, they assessed the impact of the number of mobbing individuals on the stimulus recordings, and they did so at two very different times of the year with different social contexts for the birds involved, winter (non-breeding) and spring (breeding). The experiment was well-designed and highly powered, and the authors tested and confirmed an important assumption of their design, and thus the results are convincing. It is clear that members of the local bird community responded differently to the two different species, and this result raises interesting questions about why these species differed in their tendency to attract additional mobbers. For instance, are species that recruit more co-mobbers more effective at recruiting because they are more reliable in their mobbing behavior (Magrath et al. 2014), more likely to reciprocate (Krams and Krama, 2002), or for some other reason? Hopefully this system, now of proven utility thanks to the current study, will be useful for following up on hypotheses such as these. Other convincing results, such as the higher rate of mobbing response in winter than in spring, also merit following up with further work. Finally, their observation that playback of vocalizations of multiple individuals often elicited a more mobbing response that the playback of vocalizations of a single individual are interesting and consistent with other recent work indicating that groups of mobbers recruit more additional mobbers than do single mobbers (Dutour et al. 2021). However, as acknowledged in the manuscript, the design of the current study did not allow a distinction between the effect of multiple individuals signaling versus an effect of a stronger stimulus. Thus, this last result leaves the question of the effect of mobbing group size in these species open to further study. REFERENCES Dutour M, Kalb N, Salis A, Randler C (2021) Number of callers may affect the response to conspecific mobbing calls in great tits (Parus major). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 75, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-02969-7 Krams I, Krama T (2002) Interspecific reciprocity explains mobbing behaviour of the breeding chaffinches, Fringilla coelebs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 269, 2345–2350. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2155 Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN (2015) Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biological Reviews, 90, 560–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12122 Salis A, Lena JP, Lengagne T (2023) Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490715, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715 | Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community | Ambre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne | <p>Heterospecific communication is common for birds when mobbing a predator. However, joining the mob should depend on the number of callers already enrolled, as larger mobs imply lower individual risks for the newcomer. In addition, some ‘communi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Community ecology, Social structure | Tim Parker | 2022-05-06 09:29:30 | View | ||

01 Mar 2023

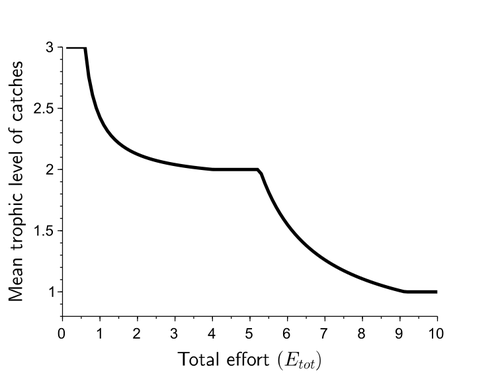

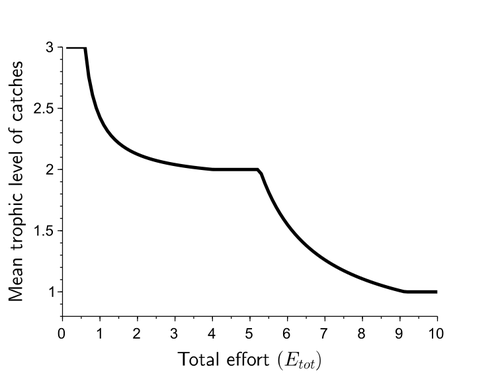

Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systemsEric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/290460Adaptive harvesting, “fishing down the food web”, and regime shiftsRecommended by Amanda Lynn Caskenette based on reviews by Pierre-Yves HERNVANN and 1 anonymous reviewerThe mean trophic level of catches in world fisheries has generally declined over the 20th century, a phenomenon called "fishing down the food web" (Pauly et al. 1998). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this decline including the collapse of, or decline in, higher trophic level stocks leading to the inclusion of lower trophic level stocks in the fishery. Fishing down the food web may lead to a reduction in the resilience, i.e., the capacity to rebound from change, of the fished community, which is concerning given the necessity of resilience in the face of climate change. The practice of adaptive harvesting, which involves fishing stocks based on their availability, can also result in a reduction in the average trophic level of a fishery (Branch et al. 2010). Adaptive harvesting, similar to adaptive foraging, can affect the resilience of fisheries. Generally, adaptive foraging acts as a stabilizing force in communities (Valdovinos et al. 2010), however it is not clear how including harvesters as the adaptive foragers will affect the resilience of the system. Tromeur and Loeuille (2023) analyze the effects of adaptively harvesting a trophic community. Using a system of ordinary differential equations representing a predator-prey model where both species are harvested, the researchers mathematically analyze the impact of increasing fishing effort and adaptive harvesting on the mean trophic level and resilience of the fished community. This is achieved by computing the equilibrium densities and equilibrium allocation of harvest effort. In addition, the researchers numerically evaluate adaptive harvesting in a tri-trophic system (predator, prey, and resource). The study focuses on the effect of adaptively distributing harvest across trophic levels on the mean trophic level of catches, the propensity for regime shifts to occur, the ability to return to equilibrium after a disturbance, and the speed of this return. The results indicate that adaptive harvesting leads to a decline in the mean trophic level of catches, resulting in “fishing down the food web”. Furthermore, the study shows that adaptive harvesting may harm the overall resilience of the system. Similar results were observed numerically in a tri-trophic community. While adaptive foraging is generally a stabilizing force on communities, the researchers found that adaptive harvesting can destabilize the harvested community. One of the key differences between adaptive foraging models and the model presented here, is that the harvesters do not exhibit population dynamics. This lack of a numerical response by the harvesters to decreasing population sizes of their stocks leads to regime shifts. The realism of a fishery that does not respond numerically to declining stock is debatable, however it is very likely that there will a least be significant delays due to social and economic barriers to leaving the fishery, that will lead to similar results. This study is not unique in demonstrating the ability of adaptive harvesting to result in “fishing down the food web”. As pointed out by the researchers, the same results have been shown with several different model formulations (e.g., age and size structured models). Similarly, this study is not unique to showing that increasing adaptation speeds decreases the resilience of non-linear predator-prey systems by inducing oscillatory behaviours. Much of this can be explained by the destabilising effect of increasing interaction strengths on food webs (McCann et al. 1998). By employing a straightforward model, the researchers were able to demonstrate that adaptive harvesting, a common strategy employed by fishermen, can result in a decline in the average trophic level of catches, regime shifts, and reduced resilience in the fished community. While previous studies have observed some of these effects, the fact that the current study was able to capture them all with a simple model is notable. This modeling approach can offer insight into the role of human behavior on the complex dynamics observed in fisheries worldwide. References Branch, T. A., R. Watson, E. A. Fulton, S. Jennings, C. R. McGilliard, G. T. Pablico, D. Ricard, et al. 2010. The trophic fingerprint of marine fisheries. Nature 468:431–435. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09528 Tromeur, E., and N. Loeuille. 2023. Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems. bioRxiv 290460, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/290460 McCann, K., A. Hastings, and G.R. Huxel. 1998. Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature 395: 794-798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427 Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Froese, and F. Torres Jr. 1998. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–86. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860 Valdovinos, F.S., R. Ramos-Jiliberto, L. Garay-Naravez, P. Urbani, and J.A. Dunne. 2010. Consequences of adaptive behaviour for the structure and dynamics of food webs. Ecology Letters 13: 1546-1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01535.x | Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems | Eric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Many world fisheries display a declining mean trophic level of catches. This "fishing down the food web" is often attributed to reduced densities of high-trophic-level species. We show here that the fishing down pattern can actually emerge from... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Amanda Lynn Caskenette | 2022-05-03 21:09:35 | View | |

09 Nov 2023

Mark loss can strongly bias estimates of demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasetsFrédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485763Marks lost in action, biased estimationsRecommended by Sylvain Billiard based on reviews by Olivier Gimenez, Devin Johnson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Olivier Gimenez, Devin Johnson and 1 anonymous reviewer

Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) data are commonly used to estimate ecological variables such as abundance, survival probability, or transition rates from one state to another (e.g. from juvenile to adult, or migration from one site to another). Many studies have shown how estimations can be affected by neglecting one aspect of the population under study (e.g. the heterogeneity in survival between individuals) or one limit of the methodology itself (e.g. the fact that observers might not detect an individual although it is still alive). Strikingly, very few studies have yet assessed the robustness of one fundamental assumption of all CMR-based inferences: marks are supposed definitive and immutable. If they are not, how are estimations affected? Addressing this issue is the main goal of the paper by Touzalin et al. (2023), and they did a very nice work. But, because the answer is not that simple, it also calls for further investigations. When and why would mark loss bias estimation? In at least two situations. First, when estimating survival rates: if an individual loses its mark, it will be considered as dead, hence death rates will be overestimated. Second, more subtly, when estimating transition rates: if one individual loses its mark at the specific moment where its state changes, then a transition will be missed in data. The history of the marked individual would then be split into two independent CMR sequences as if there were two different individuals, including one which died. Touzalin et al. (2023) thoroughly studied these two situations by estimating ecological parameters on 1) well-thought simulated datasets, that cover a large range of possible situations inspired from a nice compilation of hundreds of estimations from fish and bats studies, and 2) on their own bats dataset, for which they had various sources of information about mark losses, i.e. different mark types on the same individuals, including mark based on genotypes, and marks found on the soil in the place where bats lived. Their main findings from the simulated datasets are that there is a general trend for underestimation of survival and transition rates if mark loss is not accounting for in the model, as it would be intuitively expected. However, they also showed from the bats dataset that biases do not show any obvious general trend, suggesting complex interactions between different ecological processes and/or with the estimation procedure itself. The results by Touzalin et al. (2023) strongly suggest that mark loss should systematically be included in models estimating parameters from CMR data. In addition to adapt the inferential models, the authors also recommend considering either a double marking, or even a single but ‘permanent’ mark such as one based on the genotypes. However, the potential gain of a double marking or of the use of genotypes is still to be evaluated both in theory and practice, and it seems to be not that obvious at first sight. First because double marking can be costly for experimenters but also for the marked animals, especially as several studies showed that marks can significantly affect survival or recapture rates. Second because multiple sources of errors can affect genotyping, which would result in wrong individual assignations especially in populations with low genetic diversity or high inbreeding, or no individual assignation at all, which would increase the occurrence of missing data in CMR datasets. Touzalin et al. (2023) supposed in their paper that there were no genotyping errors, but one can doubt it to be true in most situations. They have now important and interesting other issues to address. References Frédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille (2023) Mark loss can strongly bias demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasets. BioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.25.485763 | Mark loss can strongly bias estimates of demographic rates in multi-state models: a case study with simulated and empirical datasets | Frédéric Touzalin, Eric J. Petit, Emmanuelle Cam, Claire Stagier, Emma C. Teeling, Sébastien J. Puechmaille | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. The development of methods for individual identification in wild species and the refinement of Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) models over the past few decades have greatly improved the assessment of population demo... | Conservation biology, Demography | Sylvain Billiard | 2022-04-12 18:49:34 | View | ||

25 Nov 2022

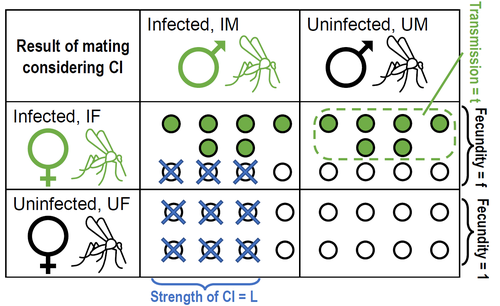

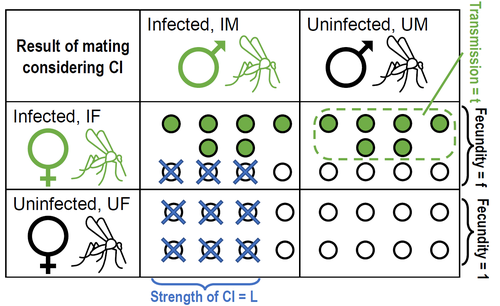

Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populationsPetteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824Population dynamics of Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeRecommended by Jorge Peña based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers"Good and evil are so close as to be chained together in the soul" Maternally inherited symbionts—microorganisms that pass from a female host to her progeny—have two main ways of increasing their own fitness. First, they can increase the fecundity or viability of infected females. This “positive fitness effects” strategy is the one commonly used by mutualistic symbionts, such as Buchnera aphidicola—the bacterial endosymbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum [4]. Second, maternally inherited symbionts can manipulate the reproduction of infected females in a way that enhances symbiont transmission at the expense of host fitness. A famous example of this “reproductive parasitism” strategy is the cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) [3] induced by bacteria of the genus Wolbachia in their arthropod and nematode hosts. CI works as a toxin-antidote system, whereby the sperm of infected males is modified in a lethal way (toxin) that can only be reverted if the egg is also infected (antidote) [1]. As a result, CI imposes a kind of conditional sterility on their hosts: while infected females are compatible with both infected and uninfected males, uninfected females experience high offspring mortality if (and only if) they mate with infected males [7]. These two symbiont strategies (positive fitness effects versus reproductive parasitism) have been traditionally studied separately, both empirically and theoretically. However, it has become clear that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive, and that a reproductive parasite can simultaneously act as a mutualist—an infection type that has been dubbed “Jekyll and Hyde” [6], after the famous novella by Robert Louis Stevenson about kind scientist Dr. Jekyll and his evil alter ego, Mr. Hyde. In important previous work, Zug and Hammerstein [7] analyzed the consequences of positive fitness effects on the dynamics of different kind of infections, including “Jekyll and Hyde” infections characterized by CI and other reproductive parasitism strategies. Building on this and related modeling framework, Karisto et al. [2] re-investigate and expand on the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism in Wolbachia infections by focusing on CI in both diplodiploid and haplodiploid populations, and by paying particular attention to the mathematical assumption structure underlying their results. Karisto et al. begin by reviewing classic models of Wolbachia infections in diplodiploid populations that assume a “negative fitness effect” (modeled as a fertility penalty on infected females), characteristic of a pure strategy of reproductive parasitism. Together with the positive frequency-dependent effects due to CI (whereby the fitness benefits to symbionts infecting females increase with the proportion of infected males in the population) this results in population dynamics characterized by two stable equilibria (the Wolbachia-free state and an interior equilibrium with a high frequency of Wolbachia-carrying hosts) separated by an unstable interior equilibrium. Wolbachia can then spread once the initial frequency is above a threshold or an invasion barrier, but is prevented from fixing by a proportion of infections failing to be passed on to offspring. Karisto et al. show that, given the assumption of negative fitness effects, the stable interior equilibrium can never feature a Wolbachia prevalence below one-half. Moreover, they convincingly argue that a prevalence greater than but close to one-half is difficult to maintain in the presence of stochastic fluctuations, as in these cases the high-prevalence stable equilibrium would be too close to the unstable equilibrium signposting the invasion barrier. Karisto et al. then relax the assumption of negative fitness effects and allow for positive fitness effects (modeled as a fertility premium on infected females) in a diplodiploid population. They show that positive fitness effects may result in situations where the original invasion threshold is now absent, the bistable coexistence dynamics are transformed into purely co-existence dynamics, and Wolbachia symbionts can now invade when rare. Karisto et al. conclude that positive fitness effects provide a plausible and potentially testable explanation for the low frequencies of symbiont-carrying hosts that are sometimes observed in nature, which are difficult to reconcile with the assumption of negative fitness effects. Finally, Karisto et al. extend their analysis to haplodiploid host populations (where all fertilized eggs develop as females). Here, they investigate two types of cytoplasmic incompatibility: a female-killing effect, similar to the CI effect studied in diplodiploid populations (the “Leptopilina type” of Vavre et al. [5]) and a masculinization effect, where CI leads to the loss of paternal chromosomes and to the development of the offspring as a male (the “Nasonia type” of Vavre et al. [5]). The models are now two-sex, which precludes a complete analytical treatment, in particular regarding the stability of fixed points. Karisto et al. compensate by conducting large numerical analyses that support their claims. Importantly, all main conclusions regarding the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism continue to hold under haplodiploidy. All in all, the analysis and results by Karisto et al. suggest that it is not necessary to resort to classical (but depending on the situation, unlikely) mechanisms, such as ongoing invasion or source-sink dynamics, to explain arthropod populations featuring low-prevalent Wolbachia infections. Instead, low-frequency equilibria might be simply due to reproductive parasites conferring beneficial fitness effects, or Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll (positive fitness effects) and Mr. Hyde (cytoplasmatic incompatibility). References [1] Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, Weill M, Sicard M, Charlat S (2019) The Toxin–Antidote Model of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Genetics and Evolutionary Implications. Trends in Genetics, 35, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2018.12.004 [2] Karisto P, Duplouy A, Vries C de, Kokko H (2022) Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations. bioRxiv, 2022.04.11.487824, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824 [3] Laven H (1956) Cytoplasmic Inheritance in Culex. Nature, 177, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/177141a0 [4] Perreau J, Zhang B, Maeda GP, Kirkpatrick M, Moran NA (2021) Strong within-host selection in a maternally inherited obligate symbiont: Buchnera and aphids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2102467118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102467118 [5] Vavre F, Fleury F, Varaldi J, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M (2000) Evidence for Female Mortality in Wolbachia-Mediated Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Haplodiploid Insects: Epidemiologic and Evolutionary Consequences. Evolution, 54, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00019.x [6] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2015) Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biological Reviews, 90, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12098 [7] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2018) Evolution of reproductive parasites with direct fitness benefits. Heredity, 120, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0022-5 | Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations | Petteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">The bacterial endosymbiont <em>Wolbachia</em> is best known for its ability to modify its host’s reproduction by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) to facilitate its own spread. Classical models predict eithe... |  | Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology | Jorge Peña | 2022-04-12 12:52:55 | View | |

03 Jun 2022

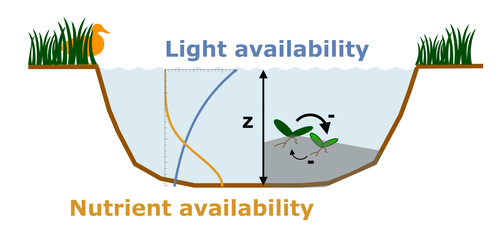

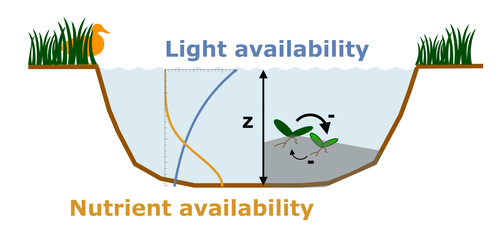

Evolutionary emergence of alternative stable states in shallow lakesAlice Ardichvili, Nicolas Loeuille, Vasilis Dakos https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.23.481597How to evolve an alternative stable stateRecommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewer

Alternative stable states describe ecosystems that can persist in more than one configuration. An ecosystem can shift between stable states following some form of perturbation. There has been much work on predicting when ecosystems will shift between stable states, but less work on why some ecosystems are able to exist in alternative stable states in the first place. The paper by Ardichvili, Loeuille, and Dakos (2022) addresses this question using a simple model of a shallow lake. Their model is based on a trade-off between access to light and nutrient availability in the water column, two essential resources for the macrophytes they model. They then identify conditions when the ancestral macrophyte will diversify resulting in macrophyte species living at new depths within the lake. The authors find a range of conditions where alternative stable states can evolve, but the range is narrow. Nonetheless, their model suggests that for alternative stable states to exist, one requirement is for there to be asymmetric competition between competing species, with one species being a better competitor on one limiting resource, with the other being a better competitor on a second limiting resource. These results are interesting and add to growing literature on how asymmetric competition can aid species coexistence. Asymmetric competition may be widespread in nature, with closely related species often being superior competitors on different resources. Incorporating asymmetric competition, and its evolution, into models does complicate theoretical investigations, but Ardichvili, Loeuille, and Dakos’ paper elegantly shows how substantial progress can be made with a model that is still (relatively) simple. References Ardichvili A, Loeuille N, Dakos V (2022) Evolutionary emergence of alternative stable states in shallow lakes. bioRxiv, 2022.02.23.481597, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.23.481597 | Evolutionary emergence of alternative stable states in shallow lakes | Alice Ardichvili, Nicolas Loeuille, Vasilis Dakos | <p style="text-align: justify;">Ecosystems under stress may respond abruptly and irreversibly through tipping points. Although much is explored on the mechanisms that affect tipping points and alternative stable states, little is known on how ecos... |  | Community ecology, Competition, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Theoretical ecology | Tim Coulson | 2022-03-01 10:54:05 | View | |

24 May 2022

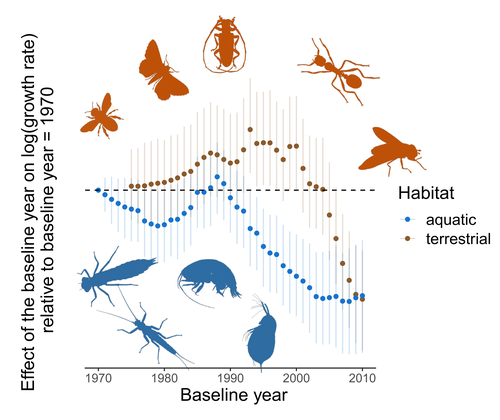

Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline?François Duchenne, Emmanuelle Porcher, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Grégoire Loïs, Colin Fontaine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.479422Don't jump to conclusions on arthropod abundance dynamics without appropriate dataRecommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Gabor L Lovei and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Gabor L Lovei and 1 anonymous reviewer

Humans are dramatically modifying many aspects of our planet via increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, patterns of land-use change, and unsustainable exploitation of the planet’s resources. These changes impact the abundance of species of wild organisms, with winners and losers. Identifying how different species and groups of species are influenced by anthropogenic activity in different biomes, continents, and habitats, has become a pressing scientific question with many publications reporting analyses of disparate data on species population sizes. Many conclusions are based on the linear analysis of rather short time series of organismal abundances. Duchenne F, Porcher E, Mihoub J-B, Loïs G, Fontaine C (2022) Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? bioRxiv, 2022.02.09.479422, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.479422 | Controversy over the decline of arthropods: a matter of temporal baseline? | François Duchenne, Emmanuelle Porcher, Jean-Baptiste Mihoub, Grégoire Loïs, Colin Fontaine | <p style="text-align: justify;">Recently, a number of studies have reported somewhat contradictory patterns of temporal trends in arthropod abundance, from decline to increase. Arthropods often exhibit non-monotonous variation in abundance over ti... |  | Conservation biology | Tim Coulson | 2022-02-11 15:44:44 | View | |

31 May 2022

Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill populationNikolaos Smit, Alice Baniel, Berta Roura-Torres, Paul Amblard-Rambert, Marie J. E. Charpentier, Elise Huchard https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.07.479393Rare behaviours can have strong effects: evidence for sexual coercion in mandrillsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Micaela Szykman Gunther and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Micaela Szykman Gunther and 1 anonymous reviewer

Sexual coercion can be defined as the use by a male of force, or threat of force, which increases the chances that a female will mate with him at a time when she is likely to be fertile, and/or decrease the chances that she will mate with other males, at some cost to the female (Smuts & Smuts 1993). It has been evidenced in a wide range of species and may play an important role in the evolution of sexual conflict and social systems. However, identifying sexual coercion in natural systems can be particularly challenging. Notably, while male behaviour may have immediate consequences on mating success (“harassment”), the mating benefits may be delayed in time (“intimidation”), and in such cases, evidencing coercion requires detailed temporal data at the individual level. Moreover, in some species male aggressive behaviours may be subtle or rare and hence hardly observed, yet still have important effects on female mating probability and fitness. Therefore, investigating the occurrence and consequences of sexual coercion in such species is particularly relevant but studying it in a statistically robust way is likely to require a considerable amount of time spent observing individuals. In this paper, Smit et al. (2022) test three clear predictions of the sexual coercion hypothesis in a natural population of Mandrills, where severe male aggression towards females is rare: (1) male aggression is more likely on sexually receptive females than on females in other reproductive states, (2) receptive females are more likely to be injured and (3) male aggression directed towards females is positively related to subsequent probability of copulation between those dyads. They also tested an alternative hypothesis, the “aggressive male phenotype” under which the correlation between male aggression towards females and subsequent mating could be statistically explained by male overall aggressivity. In agreement with the three predictions of the sexual coercion hypothesis, (1) male aggression was on average 5 times more likely, and (2) injuries twice as likely, to be observed on sexually receptive females than on females in other reproductive states and (3) copulation between males and sexually receptive females was twice more likely to be observed when aggression by this male was observed on the female before sexual receptivity. There was no support for the aggressive male hypothesis. The reviewers and I were highly positive about this study, notably regarding the way it is written and how the predictions are carefully and clearly stated, tested, interpreted, and discussed. This study is a good illustration of a case where some behaviours may not be common or obvious yet have strong effects and likely important consequences and thus be clearly worth studying. More generally, it shows once more the importance of detailed long-term studies at the individual level for our understanding of the ecology and evolution of wild populations. It is also a good illustration of the challenges faced, when comparing the likelihood of contrasting hypotheses means we need to alter sample sizes and/or the likelihood to observe at all some behaviours. For example, observing copulation within minutes after aggression (and therefore, showing statistical support for “harassment”) is inevitably less likely than observing copulations on the longer-term (and therefore showing statistical support for “intimidation”, when of course effort is put into recording such behavioural data on the long-term). Such challenges might partly explain some apparently intriguing results. For example, why are swollen females more aggressed by males if only aggression before the swollen period seems associated with more chances of mating? Here, the authors systematically provide effect sizes (and confidence intervals) and often describe the effects in an intuitive biological way (e.g., “Swollen females were, on average, about five times more likely to become injured”). This clearly helps the reader to not merely compare statistical significances but also the biological strengths of the estimated effects and the uncertainty around them. They also clearly acknowledge limits due to sample size when testing the harassment hypothesis, yet they provide precious information on the probability of observing mating (a rare behaviour) directly after aggression (already a rare behaviour!), that is, 3 times out of 38 aggressions observed between a male and a swollen female. Once again, this highlights how important it is to be able to pursue the enormous effort put so far into closely and continuously monitoring this wild population. Finally, this study raises exciting new questions, notably regarding to what extent females exhibit “counter-strategies” in response to sexual coercion, notably whether there is still scope for female mate choice under such conditions, and what are the fitness consequences of these dynamic conflicting sexual interactions. No doubt these questions will sooner than later be addressed by the authors, and I am looking forward to reading their upcoming work. References Smit N, Baniel A, Roura-Torres B, Amblard-Rambert P, Charpentier MJE, Huchard E (2022) Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill population. bioRxiv, 2022.02.07.479393, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.07.479393 Smuts BB, Smuts R w. (1993) Male Aggression and Sexual Coercion of Females in Nonhuman Primates and Other Mammals: Evidence and Theoretical Implications. In: Advances in the Study of Behavior (eds Slater PJB, Rosenblatt JS, Snowdon CT, Milinski M), pp. 1–63. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3454(08)60404-0 | Sexual coercion in a natural mandrill population | Nikolaos Smit, Alice Baniel, Berta Roura-Torres, Paul Amblard-Rambert, Marie J. E. Charpentier, Elise Huchard | <p style="text-align: justify;">Increasing evidence indicates that sexual coercion is widespread. While some coercive strategies are conspicuous, such as forced copulation or sexual harassment, less is known about the ecology and evolution of inti... |  | Behaviour & Ethology | Matthieu Paquet | 2022-02-11 09:32:49 | View | |

14 Nov 2022

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture modelsCécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bearRecommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated. Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008. Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007 Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135. Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025 Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719 | Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models | Cécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez | <p>Estimating the size of small populations of large mammals can be achieved via censuses, or complete counts, of recognizable individuals detected over a time period: minimum detected (population) size (MDS). However, as a population grows larger... |  | Conservation biology, Demography, Population ecology | Nicolas BECH | 2022-01-20 10:49:59 | View | |

15 May 2023

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new contextLogan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xsAn experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativenessRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer

Whether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014). Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027 Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019) Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs | Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context | Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. Howev... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-01-13 19:08:52 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle