Latest recommendations

| Id▼ | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

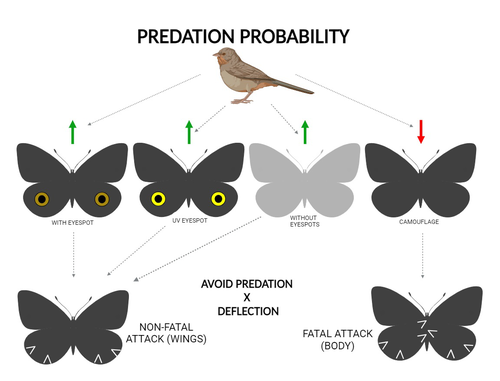

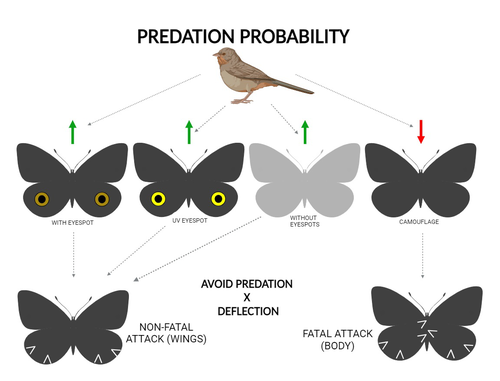

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

15 Feb 2024

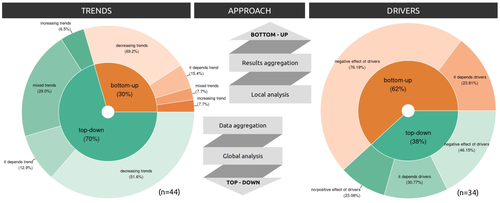

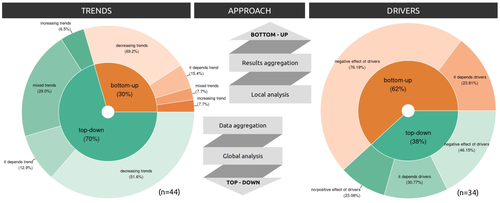

Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trendsMaelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3HUnraveling the Complexity of Global Biodiversity Dynamics: Insights and ImperativesRecommended by Paulo Borges based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Pedro Cardoso and 1 anonymous reviewer

Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across terrestrial and marine ecosystems, driven by various processes that degrade habitats and threaten species with extinction. Despite the urgency of this issue, empirical studies present a mixed picture, with some indicating declining trends while others show more complex patterns. In a recent effort to better understand global biodiversity dynamics, Boennec et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive literature review examining temporal trends in biodiversity. Their analysis reveals that reviews and meta-analyses, coupled with the use of global indicators, tend to report declining trends more frequently. Additionally, the study underscores a critical gap in research: the scarcity of investigations into the combined impact of multiple pressures on biodiversity at a global scale. This lack of understanding complicates efforts to identify the root causes of biodiversity changes and develop effective conservation strategies. This study serves as a crucial reminder of the pressing need for long-term biodiversity monitoring and large-scale conservation studies. By filling these gaps in knowledge, researchers can provide policymakers and conservation practitioners with the insights necessary to mitigate biodiversity loss and safeguard ecosystems for future generations. References Boennec, M., Dakos, V. & Devictor, V. (2023). Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trend. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X29W3H

| Sources of confusion in global biodiversity trends | Maelys Boennec, Vasilis Dakos, Vincent Devictor | <p>Populations and ecological communities are changing worldwide, and empirical studies exhibit a mixture of either declining or mixed trends. Confusion in global biodiversity trends thus remains while assessing such changes is of major social, po... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Meta-analyses | Paulo Borges | 2023-09-20 11:10:25 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

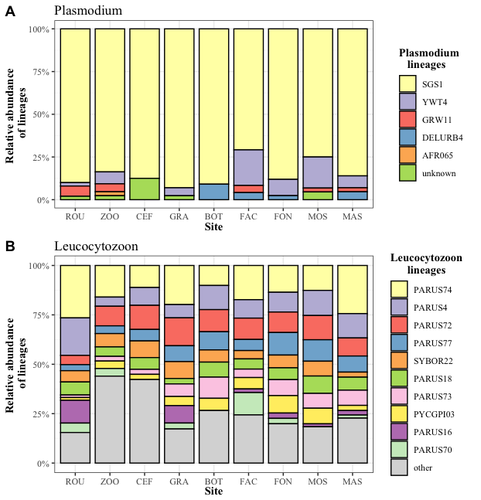

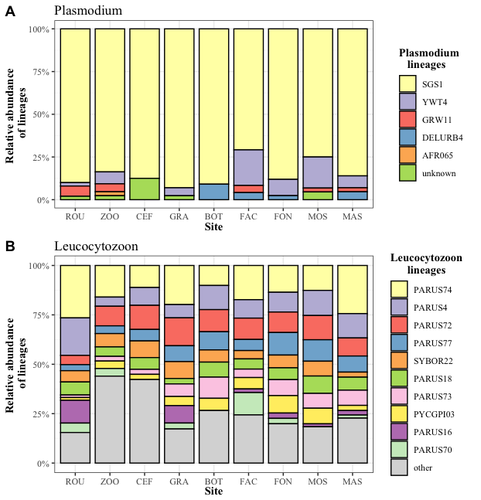

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

12 Jan 2024

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonisAlexius Folk, Adele Mennerat https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695Marking invertebrates using RFID tagsRecommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer

Guiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically. The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it. References Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013 Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008. Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695 Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082 Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900 | Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse *Lepeophtheirus salmonis* | Alexius Folk, Adele Mennerat | <p style="text-align: justify;">Monitoring individuals within populations is a cornerstone in evolutionary ecology, yet individual tracking of invertebrates and particularly parasitic organisms remains rare. To address this gap, we describe here a... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Marine ecology, Parasitology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-09-04 15:25:08 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

23 Oct 2023

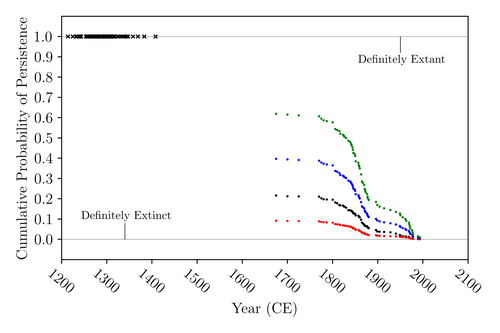

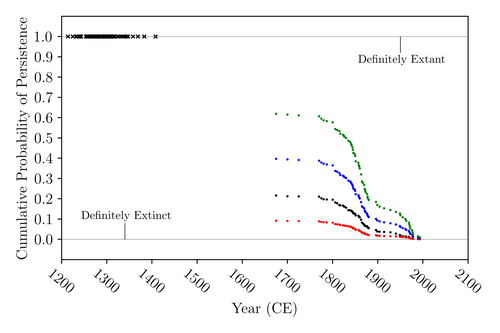

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

19 Mar 2024

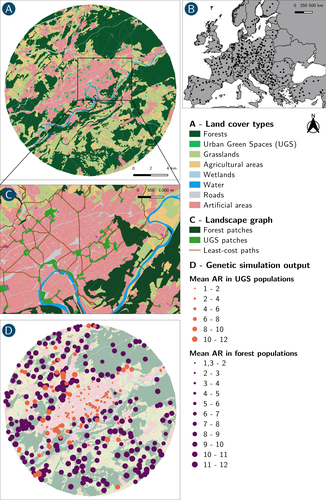

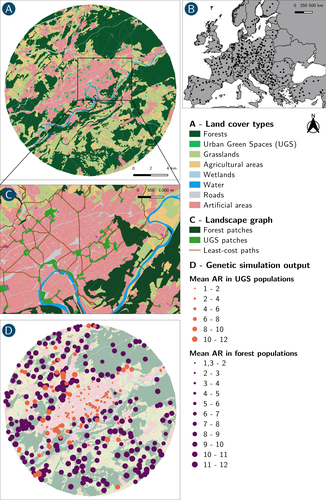

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle