Sex makes them sleepy: host reproductive status induces diapause in a parasitoid population experiencing harsh winters

Tougeron K., Brodeur J., van Baaren J., Renault D. and Le Lann C.

https://doi.org/10.1101/371385

The response of interacting species to biotic seasonal cues

Recommended by Adele Mennerat and Enric Frago based on reviews by Anne Duplouy and 1 anonymous reviewer

In temperate regions, food abundance and quality vary greatly throughout the year, and the ability of organisms to synchronise their phenology to these changes is a key determinant of their reproductive success. Successful synchronisation requires that cues are perceived prior to change, leaving time for physiological adjustments.

But what are the cues used to anticipate seasonal changes? Abiotic factors like temperature and photoperiod are known for their driving role in the phenology of a wide range of plant an animal species [1,2] . Arguably though, biotic cues directly linked to upcoming changes in food abundance could be as important as abiotic factors, but the response of organisms to these cues remains relatively unexplored.

Biotic cues may be particularly important for higher trophic levels because of their tight interaction with the hosts or preys they depend on. In this study Tougeron and colleagues [3] address this topic using interacting insects, namely herbivorous aphids and the parasitic wasps (or parasitoids) that feed on them. The key finding of the study by Tougeron et al. [3] is that the host morph in which parasitic wasp larvae develop is a major driver of diapause induction. More importantly, the aphid morph that triggers diapause in the wasp is the one that will lay overwintering eggs in autumn at the onset of harsh winter conditions. Its neatly designed experimental setup also provides evidence that this response may vary across populations as host-dependent diapause induction was only observed in a wasp population that originated from a cold area. As the authors suggests, this may be caused by local adaptation to environmental conditions because, relative to warmer regions, missing the time window to enter diapause in colder regions may have more dramatic consequences. The study also shows that different aphid morphs differ greatly in their chemical composition, and points to particular types of metabolites like sugars and polyols as specific cues for diapause induction.

This study provides a nice example of the complexity of biological interactions, and of the importance of phenological synchrony between parasites and their hosts. The authors provide evidence that phenological synchrony is likely to be achieved via chemical cues derived from the host. A similar approach was used to demonstrate that the herbivorous beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata uses plant chemical cues to enter diapause [4]. Beetles fed on plants exposed to pre-wintering conditions entered diapause in higher proportions than those fed on control plants grown at normal conditions. As done by Tougeron et al. [3], in [4] the authors associated diapause induction to changes in the composition of metabolites in the plant. In both studies, however, the missing piece is to unveil the particular chemical involved, an answer that may be provided by future experiments.

Latitudinal clines in diapause induction have been described in a number of insect species [5]. Correlative studies, in which the phenology of different trophic levels has been monitored, suggest that these clines may in part be governed by lower trophic levels. For example, Phillimore et al. [6] explored the relative contribution of temperature and of host plant phenology on adult flight periods of the butterfly Anthocharis cardamines. Tougeron et al. [3], by using aphids and their associated parasitoids, take the field further by moving from observational studies to experiments. Besides, aphids are not only a tractable host-parasite system in the laboratory, they are important agricultural pests. Improving our basic knowledge of their ecological interactions may ultimately contribute to improving pest control techniques. The study by Tougeron et al. [3] exemplifies the multiple benefits that can be gained from addressing fundamental questions in species that are also directly relevant to society.

References

[1] Tauber, M. J., Tauber, C. A., and Masaki, S. (1986). Seasonal Adaptations of Insects. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

[2] Bradshaw, W. E., and Holzapfel, C. M. (2007). Evolution of Animal Photoperiodism. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 38(1), 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110115

[3] Tougeron, K., Brodeur, J., Baaren, J. van, Renault, D., and Lann, C. L. (2019b). Sex makes them sleepy: host reproductive status induces diapause in a parasitoid population experiencing harsh winters. bioRxiv, 371385, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/371385

[4] Izzo, V. M., Armstrong, J., Hawthorne, D., and Chen, Y. (2014). Time of the season: the effect of host photoperiodism on diapause induction in an insect herbivore, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Ecological Entomology, 39(1), 75–82. doi: 10.1111/een.12066

[5] Hut Roelof A., Paolucci Silvia, Dor Roi, Kyriacou Charalambos P., and Daan Serge. (2013). Latitudinal clines: an evolutionary view on biological rhythms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1765), 20130433. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0433

[6] Phillimore, A. B., Stålhandske, S., Smithers, R. J., and Bernard, R. (2012). Dissecting the Contributions of Plasticity and Local Adaptation to the Phenology of a Butterfly and Its Host Plants. The American Naturalist, 180(5), 655–670. doi: 10.1086/667893

| Sex makes them sleepy: host reproductive status induces diapause in a parasitoid population experiencing harsh winters | Tougeron K., Brodeur J., van Baaren J., Renault D. and Le Lann C. | <p>When organisms coevolve, any change in one species can induce phenotypic changes in traits and ecology of the other species. The role such interactions play in ecosystems is central, but their mechanistic bases remain underexplored. Upper troph... |  | Coexistence, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Physiology | Adele Mennerat | | 2018-07-18 18:51:03 | View |

Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse

Charlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech

https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512

An experimental approach for understanding how terrestrial isopods respond to environmental stressors

Recommended by Aniruddha Belsare based on reviews by Aaron Yilmaz and Michael Morris

In this article, the authors discuss the results of their study investigating the effects of heat stress and moisture stress on a terrestrial isopod Armadilldium vulgare, the common woodlouse [1]. Specifically, the authors have assessed how increased temperature or decreased moisture affects life history traits (such as growth, survival, and reproduction) as well as physiological traits (immune cell parameters and \( beta \)-galactosidase activity). This article quantitatively evaluates the effects of the two stressors on woodlouse. Terrestrial isopods like woodlouse are sensitive to thermal and moisture stress [2; 3] and are therefore good models to test hypotheses in global change biology and for monitoring ecosystem health.

An important feature of this study is the combination of experimental, laboratory, and analytical techniques. Experiments were conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory by modulating temperature and moisture, life history and physiological traits were measured/analyzed and then tested using models. Both stressors had negative impacts on survival and reproduction of woodlouse, and result in premature ageing. Although thermal stress did not affect survival, it slowed woodlouse growth. Moisture stress did not have a detectable effect on woodlouse growth but decreased survival and reproductive success. An important insight from this study is that effects of heat and moisture stressors on woodlouse are not necessarily linear, and experimental approaches can be used to better elucidate the mechanisms and understand how these organisms respond to environmental stress.

This article is timely given the increasing attention on biological monitoring and ecosystem health.

References:

[1] Depeux C, Branger A, Moulignier T, Moreau J, Lemaître J-F, Dechaume-Moncharmont F-X, Laverre T, Pauhlac H, Gaillard J-M, Beltran-Bech S (2022) Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse. bioRxiv, 2022.09.26.509512., ver. 3 peer-reviewd and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512

[2] Warburg MR, Linsenmair KE, Bercovitz K (1984) The effect of climate on the distribution and abundance of isopods. In: Sutton SL, Holdich DM, editors. The Biology of Terrestrial Isopods. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 339–367.

[3] Hassall M, Helden A, Goldson A, Grant A (2005) Ecotypic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity in reproductive traits of Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda: Oniscidea). Oecologia 143: 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1772-3

| Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse | Charlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech | <p>We tested independently the influences of increasing temperature and decreasing moisture on life history and physiological traits in the arthropod <em>Armadillidium vulgare</em>. Both increasing temperature and decreasing moisture led individua... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Life history, Physiology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Aniruddha Belsare | | 2022-09-28 13:13:47 | View |

Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.)

Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.986984

A new member of the morphometrics jungle to better monitor vulnerable lagoons

Recommended by Vincent Bonhomme based on reviews by Julien Claude and 1 anonymous reviewer

In the recent years, morphometrics, the quantitative description of shape and its covariation [1] gained considerable momentum in evolutionary ecology. Using the form of organisms to describe, classify and try to understand their diversity can be traced back at least to Aristotle. More recently, two successive revolutions rejuvenated this idea [1–3]: first, a proper mathematical refoundation of the theory of shape, then a technical revolution in the apparatus able to acquire raw data. By using a feature extraction method and planning its massive use on data acquired by aerial drones, the study by Lacaux and colleagues [4] retraces this curse of events.

The radial symmetry of Aurelia spp. jelly fish, a common species complex, is affected by stress and more largely by environmental variations, such as pollution exposition. Aurelia spp. normally present four gonads so that the proportion of non-tetramerous individuals in a population has been proposed as a biomarker [5,6].

In this study, the authors implemented the Hough transform to largely automate the detection of the gonads in Aurelia spp. Such use of the Hough transform, a long-used approach to identify shapes through edge detection, is new to morphometrics. Here, the Aurelia spp. gonads are identified as ellipses from which aspect descriptors can be derived, and primarily counted and thus can be used to quantify the proportion of individuals presenting body plans disorders.

The sample sizes studied here were too low to allow finer-grained ecophysiological investigations. That being said, the proof-of-concept is convincing and this paper paths the way for an operational and innovative approach to the ecological monitoring of sensible aquatic ecosystems.

References

[1] Kendall, D. G. (1989). A survey of the statistical theory of shape. Statistical Science, 87-99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177012589

[2] Rohlf, F. J., and Marcus, L. F. (1993). A revolution morphometrics. Trends in ecology & evolution, 8(4), 129-132. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(93)90024-J

[3] Adams, D. C., Rohlf, F. J., and Slice, D. E. (2004). Geometric morphometrics: ten years of progress following the ‘revolution’. Italian Journal of Zoology, 71(1), 5-16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/11250000409356545

[4] Lacaux, C., Desolneux, A., Gadreaud, J., Martin-Garin, B. and Thiéry, A. (2020) Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.). bioRxiv, 2020.03.11.986984, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.986984

[5] Gershwin, L. A. (1999). Clonal and population variation in jellyfish symmetry. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 79(6), 993-1000. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315499001228

[6] Gadreaud, J., Martin-Garin, B., Artells, E., Levard, C., Auffan, M., Barkate, A.-L. and Thiéry, A. (2017) The moon jellyfish as a new bioindicator: impact of silver nanoparticles on the morphogenesis. In: Mariottini GL, editor. Jellyfish: ecology, distribution patterns and human interactions. Nova Science Publishers; 2017. pp. 277–292.

| Hough transform implementation to evaluate the morphological variability of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) | Céline Lacaux, Agnès Desolneux, Justine Gadreaud, Bertrand Martin-Garin and Alain Thiéry | <p>Variations of the animal body plan morphology and morphometry can be used as prognostic tools of their habitat quality. The potential of the moon jellyfish (Aurelia spp.) as a new model organism has been poorly tested. However, as a tetramerous... |  | Morphometrics | Vincent Bonhomme | | 2020-03-18 17:40:51 | View |

Uncertain predictions of species responses to perturbations lead to underestimate changes at ecosystem level in diverse systems

Recommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by Carlos Melian and 1 anonymous reviewer

Different sources of uncertainty are known to affect our ability to predict ecological dynamics (Petchey et al. 2015). However, the consequences of uncertainty on prediction biases have been less investigated, especially when predictions are scaled up to higher levels of organisation as is commonly done in ecology for instance. The study of Orr et al. (2020) addresses this issue. It shows that, in complex systems, the uncertainty of unbiased predictions at a lower level of organisation (e.g. species level) leads to a bias towards underestimation of change at higher level of organisation (e.g. ecosystem level). This bias is strengthened by larger uncertainty and by higher dimensionality of the system.

This general result has large implications for many fields of science, from economics to energy supply or demography. In ecology, as discussed in this study, these results imply that the uncertainty of predictions of species’ change increases the probability of underestimation of changes of diversity and stability at community and ecosystem levels, especially when species richness is high. The uncertainty of predictions of species’ change also increases the probability of underestimation of change when multiple ecosystem functions are considered at once, or when the combined effect of multiple stressors is considered.

The consequences of species diversity on ecosystem functions and stability have received considerable attention during the last decades (e.g. Cardinale et al. 2012, Kéfi et al. 2019). However, since the bias towards underestimation of change increases with species diversity, future studies will need to investigate how the general statistical effect outlined by Orr et al. might affect our understanding of the well-known relationships between species diversity and ecosystem functioning and stability in response to perturbations.

References

Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, Kinzig AP, Daily GC, Loreau M, Grace JB, Larigauderie A, Srivastava DS, Naeem S (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148

Kéfi S, Domínguez‐García V, Donohue I, Fontaine C, Thébault E, Dakos V (2019) Advancing our understanding of ecological stability. Ecology Letters, 22, 1349–1356. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13340

Orr JA, Piggott JJ, Jackson A, Arnoldi J-F (2020) Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate change. bioRxiv, 2020.05.26.117200. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.26.117200

Petchey OL, Pontarp M, Massie TM, Kéfi S, Ozgul A, Weilenmann M, Palamara GM, Altermatt F, Matthews B, Levine JM, Childs DZ, McGill BJ, Schaepman ME, Schmid B, Spaak P, Beckerman AP, Pennekamp F, Pearse IS (2015) The ecological forecast horizon, and examples of its uses and determinants. Ecology Letters, 18, 597–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12443

| Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate change | James Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi | <p>Uncertainty is an irreducible part of predictive science, causing us to over- or underestimate the magnitude of change that a system of interest will face. In a reductionist approach, we may use predictions at the level of individual system com... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Theoretical ecology | Elisa Thebault | Anonymous | 2020-06-02 15:41:12 | View |

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes

Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055

A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networks

Recommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewer

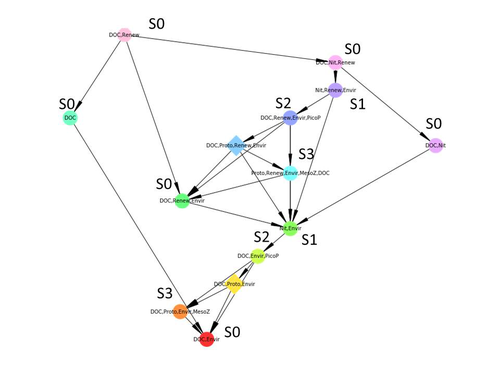

Modelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks.

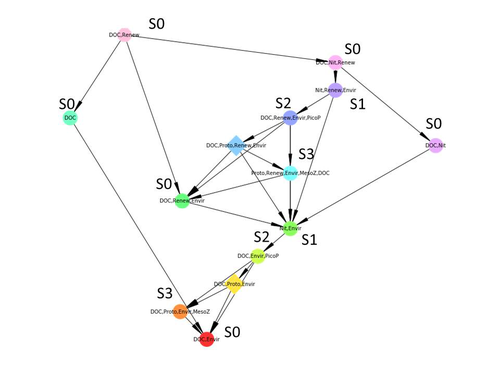

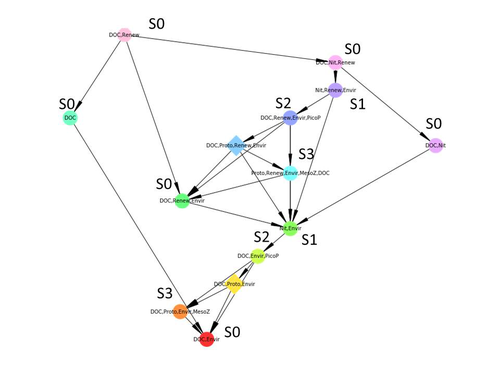

Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model.

The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed.

The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics.

Reference

Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055

| Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes | Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy | <p>Trophic interaction networks are notoriously difficult to understand and to diagnose (i.e., to identify contrasted network functioning regimes). Such ecological networks have many direct and indirect connections between species, and these conne... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Interaction networks, Microbial ecology & microbiology | Francis Raoul | Tim Coulson | 2023-07-03 10:42:34 | View |

Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades

Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne

https://doi.org/10.1101/722140

Tell me what you’ve eaten, I’ll tell you how much you’ll eat (and be eaten)

Recommended by Sara Magalhães and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 1 anonymous reviewer

Tritrophic interactions have a central role in ecological theory and applications [1-3]. Particularly, systems comprised of plants, herbivores and predators have historically received wide attention given their ubiquity and economic importance [4]. Although ecologists have long aimed to understand the forces that govern alternating ecological effects at successive trophic levels [5], several key open questions remain (at least partially) unanswered [6]. In particular, the analysis of complex food webs has questioned whether ecosystems can be viewed as a series of trophic chains [7,8]. Moreover, whether systems are mostly controlled by top-down (trophic cascades) or bottom-up processes remains an open question [6].

Traditionally, studies have addressed how species diversity at different food chain compartments affect the strength and direction of trophic cascades [9]. For example, many studies have tested whether biological control was more efficient with more than one species of natural enemies [10-12]. Much less attention has been given to the role of within-species variation in shaping trophic cascades [13]. In particular, whereas the impact of trait variation within species of plants or predators on successive trophic levels has been recently addressed [14,15], the impact of intraspecific herbivore variation is in its infancy (but see [16]). This is at odds with the resurgent acknowledgment of the importance of individual variation for several ecological processes operating at higher levels of biological organization [17].

Sources of variation within species can come in many flavours. In herbivores, striking ecological variation can be found among populations occurring on different host plants, which become genetically differentiated, thus forming host races [18,19]. Curiously, the impact of variation across host races on the strength of trophic cascades has, to date, not been explored. This is the gap that the manuscript by Sentis and colleagues [20] fills. They experimentally studied a curious tri-trophic system where the primary consumer, pea aphids, specializes in different plant hosts, creating intraspecific variation across biotypes. Interestingly, there is also ecological variation across lineages from the same biotype. The authors set up experimental food chains, where pea aphids from different lineages and biotypes were placed in their universal legume host (broad bean plants) and then exposed to a voracious but charming predator, ladybugs. The full factorial design of this experiment allowed the authors to measure vertical effects of intraspecific variation in herbivores on both plant productivity (top-down) and predator individual growth (bottom-up).

The results nicely uncover the mechanisms by which intraspecific differences in herbivores precipitates vertical modulation in food chains. Herbivore lineage and host-plant specialization shaped the strength of trophic cascades, but curiously these effects were not modulated by density-dependence. Further, ladybugs consuming pea aphids from different lineages and biotypes grew at distinct rates, revealing bottom-up effects of intraspecific variation in herbivores.

These findings are novel and exciting for several reasons. First, they show how intraspecific variation in intermediate food chain compartments can simultaneously reverberate both top-down and bottom-up effects. Second, they bring an evolutionary facet to the understanding of trophic cascades, providing valuable insights on how genetically differentiated populations play particular ecological roles in food webs. Finally, Sentis and colleagues’ findings [20] have critical implications well beyond their study systems. From an applied perspective, they provide an evident instance on how consumers’ evolutionary specialization matters for their role in ecosystems processes (e.g. plant biomass production, predator conversion rate), which has key consequences for biological control initiatives and invasive species management. From a conceptual standpoint, their results ignite the still neglected value of intraspecific variation (driven by evolution) in modulating the functioning of food webs, which is a promising avenue for future theoretical and empirical studies.

References

[1] Price, P. W., Bouton, C. E., Gross, P., McPheron, B. A., Thompson, J. N., & Weis, A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 11(1), 41-65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353

[2] Olff, H., Brown, V.K. & Drent, R.H. (1999). Herbivores: between plants and predators. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

[3] Tscharntke, T. & Hawkins, B.A. (2002). Multitrophic level interactions. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511542190

[4] Agrawal, A. A. (2000). Mechanisms, ecological consequences and agricultural implications of tri-trophic interactions. Current opinion in plant biology, 3(4), 329-335. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00089-3

[5] Pace, M. L., Cole, J. J., Carpenter, S. R., & Kitchell, J. F. (1999). Trophic cascades revealed in diverse ecosystems. Trends in ecology & evolution, 14(12), 483-488. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01723-1

[6] Abdala‐Roberts, L., Puentes, A., Finke, D. L., Marquis, R. J., Montserrat, M., Poelman, E. H., ... & Mooney, K. (2019). Tri‐trophic interactions: bridging species, communities and ecosystems. Ecology letters, 22(12), 2151-2167. doi: 10.1111/ele.13392

[7] Polis, G.A. & Winemiller, K.O. (1996). Food webs. Integration of patterns and dynamics. Chapmann & Hall, New York. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-7007-3

[8] Torres‐Campos, I., Magalhães, S., Moya‐Laraño, J., & Montserrat, M. (2020). The return of the trophic chain: Fundamental vs. realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web. Functional Ecology, 34(2), 521-533. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13470

[9] Polis, G. A., Sears, A. L., Huxel, G. R., Strong, D. R., & Maron, J. (2000). When is a trophic cascade a trophic cascade?. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 15(11), 473-475. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01971-6

[10] Sih, A., Englund, G., & Wooster, D. (1998). Emergent impacts of multiple predators on prey. Trends in ecology & evolution, 13(9), 350-355. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01437-2

[11] Diehl, E., Sereda, E., Wolters, V., & Birkhofer, K. (2013). Effects of predator specialization, host plant and climate on biological control of aphids by natural enemies: a meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50(1), 262-270. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12032

[12] Snyder, W. E. (2019). Give predators a complement: conserving natural enemy biodiversity to improve biocontrol. Biological control, 135, 73-82. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.04.017

[13] Des Roches, S., Post, D. M., Turley, N. E., Bailey, J. K., Hendry, A. P., Kinnison, M. T., ... & Palkovacs, E. P. (2018). The ecological importance of intraspecific variation. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(1), 57-64. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0402-5

[14] Bustos‐Segura, C., Poelman, E. H., Reichelt, M., Gershenzon, J., & Gols, R. (2017). Intraspecific chemical diversity among neighbouring plants correlates positively with plant size and herbivore load but negatively with herbivore damage. Ecology Letters, 20(1), 87-97. doi: 10.1111/ele.12713

[15] Start, D., & Gilbert, B. (2017). Predator personality structures prey communities and trophic cascades. Ecology letters, 20(3), 366-374. doi: 10.1111/ele.12735

[16] Turcotte, M. M., Reznick, D. N., & Daniel Hare, J. (2013). Experimental test of an eco-evolutionary dynamic feedback loop between evolution and population density in the green peach aphid. The American Naturalist, 181(S1), S46-S57. doi: 10.1086/668078

[17] Bolnick, D. I., Amarasekare, P., Araújo, M. S., Bürger, R., Levine, J. M., Novak, M., ... & Vasseur, D. A. (2011). Why intraspecific trait variation matters in community ecology. Trends in ecology & evolution, 26(4), 183-192. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.01.009

[18] Drès, M., & Mallet, J. (2002). Host races in plant–feeding insects and their importance in sympatric speciation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 357(1420), 471-492. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1059

[19] Magalhães, S., Forbes, M. R., Skoracka, A., Osakabe, M., Chevillon, C., & McCoy, K. D. (2007). Host race formation in the Acari. Experimental and Applied Acarology, 42(4), 225-238. doi: 10.1007/s10493-007-9091-0

[20] Sentis, A., Bertram, R., Dardenne, N., Simon, J.-C., Magro, A., Pujol, B., Danchin, E. and J.-L. Hemptinne (2020) Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades. bioRxiv, 722140, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/722140

| Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades | Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne | <p>Trophic cascades, the indirect effect of predators on non-adjacent lower trophic levels, are important drivers of the structure and dynamics of ecological communities. However, the influence of intraspecific trait variation on the strength of t... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Food webs, Population ecology | Sara Magalhães | | 2019-08-02 09:11:03 | View |

When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation

Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques

https://doi.org/10.1101/307322

When the dispersal of the many outruns the dispersal of the few

Recommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

Are biological invasions driven by a few pioneers, running ahead of their conspecifics? Or are these pioneers constantly being caught up by, and folded into, the larger flux of propagules from the established populations behind them?

In ecology and beyond, these two scenarios are known as "pulled" and "pushed" fronts, and they come with different expectations. In a pushed front, invasion speed is not just a matter of how good individuals are at dispersing and settling new locations. It becomes a collective, density-dependent property of population fluxes. And in particular, it can depend on the equilibrium abundance of the established populations inside the range, i.e. the species’ carrying capacity K, factoring in its abiotic environment and biotic interactions.

This realization is especially important because it can flip around our expectations about which species expand fast, and how to manage them. We tend to think of initial colonization and long-term abundance as two independent axes of variation among species or indeed as two ends of a spectrum, in the classic competition-colonization tradeoff [1]. When both play into invasion speed, good dispersers might not outrun good competitors. This is useful knowledge, whether we want to contain an invasion or secure a reintroduction.

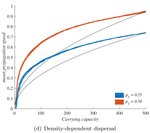

In their study "When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation", Haond et al [2] combine mathematical analysis, Individual-Based simulations and experiments to show that various mechanisms can cause pushed fronts, whose speed increases with the carrying capacity K of the species. Rather than focus on one particular angle, the authors endeavor to demonstrate that this qualitative effect appears again and again in a variety of settings.

It is perhaps surprising that this notable and general connection between K and invasion speed has managed to garner so little fame in ecology. A large fraction of the literature employs the venerable Fisher-KPP reaction-diffusion model, which combines local logistic growth with linear diffusion in space. This model has prompted both considerable mathematical developments [3] and many applications to modelling real invasions [4]. But it only allows pulled fronts, driven by the small populations at the edge of a species range, with a speed that depends only on their initial growth rate r.

This classic setup is, however, singular in many ways. Haond et al [2] use it as a null model, and introduce three mechanisms or factors that each ensure a role of K in invasion speed, while giving less importance to the pioneers at the border.

Two factors, the Allee effect and demographic stochasticity, make small edge populations slower to grow or less likely to survive. These two factors are studied theoretically, and to make their claims stronger, the authors stack the deck against K. When generalizing equations or simulations beyond the null case, it is easy to obtain functional forms where the parameter K does not only play the role of equilibrium carrying capacity, but also affects dynamical properties such as the maximum or mean growth rate. In that case, it can trivially change the propagation speed, without it meaning anything about the role of established populations behind the front. Haond et al [2] avoid this pitfall by disentangling these effects, at the cost of slightly more peculiar expressions, and show that varying essentially nothing but the carrying capacity can still impact the speed of the invasion front.

The third factor, density-dependent dispersal, makes small populations less prone to disperse. It is well established empirically and theoretically that various biological mechanisms, from collective organization to behavioral switches, can prompt organisms in denser populations to disperse more, e.g. in such a way as to escape competition [5]. The authors demonstrate how this effect induces a link between carrying capacity and invasion speed, both theoretically and in a dispersal experiment on the parasitoid wasp, Trichogramma chilonis.

Overall, this study carries a simple and clear message, supported by valuable contributions from different angles. Although some sections are clearly written for the theoretical ecology crowd, this article has something for everyone, from the stray physicist to the open-minded manager. The collaboration between theoreticians and experimentalists, while not central, is worthy of note. Because the narrative of this study is the variety of mechanisms that can lead to the same qualitative effect, the inclusion of various approaches is not a gimmick, but helps drive home its main message. The work is fairly self-contained, although one could always wish for further developments, especially in the direction of more quantitative testing of these mechanisms.

In conclusion, Haond et al [2] effectively convey the widely relevant message that, for some species, invading is not just about the destination, it is about the many offspring one makes along the way.

References

[1] Levins, R., & Culver, D. (1971). Regional Coexistence of Species and Competition between Rare Species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68(6), 1246–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1246

[2] Haond, M., Morel-Journel, T., Lombaert, E., Vercken, E., Mailleret, L., & Roques, L. (2018). When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation. BioRxiv, 307322. doi: 10.1101/307322

[3] Crooks, E. C. M., Dancer, E. N., Hilhorst, D., Mimura, M., & Ninomiya, H. (2004). Spatial segregation limit of a competition-diffusion system with Dirichlet boundary conditions. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications, 5(4), 645–665. doi: 10.1016/j.nonrwa.2004.01.004

[4] Shigesada, N., & Kawasaki, K. (1997). Biological Invasions: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press, UK.

[5] Matthysen, E. (2005). Density-dependent dispersal in birds and mammals. Ecography, 28(3), 403–416. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2005.04073.x

| When higher carrying capacities lead to faster propagation | Marjorie Haond, Thibaut Morel-Journel, Eric Lombaert, Elodie Vercken, Ludovic Mailleret & Lionel Roques | <p>This preprint has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology (https://dx.doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100004). Finding general patterns in the expansion of natural populations is a major challenge in ecology and invasion biology... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | Yuval Zelnik | 2018-04-25 10:18:48 | View |

The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair

Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen

https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe

Drivers of range expansion in a pair of sister grackle species

Recommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The spatial distribution of a species is driven by both biotic and abiotic factors that may change over time (Soberón & Nakamura, 2009; Paquette & Hargreaves, 2021). Therefore, species ranges are dynamic, especially in humanized landscapes where changes occur at high speeds (Sirén & Morelli, 2020). The distribution of many species is being reduced because of human impacts; however, some species are expanding their distributions, even over their niche (Lustenhouwer & Parker, 2022). One of the factors that may lead to a geographic niche expansion is behavioral flexibility (Mikhalevich et al., 2017), but the mechanisms determining range expansion through behavioral changes are not fully understood.

The PCI Ecology study by Summers et al. (2023) uses a very large database on the current and historic distribution of two species of grackles that have shown different trends in their distribution. The great-tailed grackle has largely expanded its range over the 20th century, while the range of the boat-tailed grackle has remained very similar. They take advantage of this differential response in the distribution of the two species and run several analyses to test whether it was a change in habitat availability, in the realized niche, in habitat connectivity or in in the other traits or conditions that previously limited the species range, what is driving the observed distribution of the species. The study finds a change in the niche of great-tailed grackle, consistent with the high behavioral flexibility of the species.

The two reviewers and I have seen a lot of value in this study because 1) it addresses a very timely question, especially in the current changing world; 2) it is a first step to better understanding if behavioral attributes may affect species’ ability to change their niche; 3) it contrasts the results using several complementary statistical analyses, reinforcing their conclusions; 4) it is based on the preregistration Logan et al (2021), and any deviations from it are carefully explained and justified in the text and 5) the limitations of the study have been carefully discussed. It remains to know if the boat-tailed grackle has more limited behavioral flexibility than the great-tailed grackle, further confirming the results of this study.

References

Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D (2021) Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html

Lustenhouwer N, Parker IM (2022) Beyond tracking climate: Niche shifts during native range expansion and their implications for novel invasions. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14395

Mikhalevich I, Powell R, Logan C (2017) Is behavioural flexibility evidence of cognitive complexity? How evolution can inform comparative cognition. Interface Focus, 7, 20160121. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121

Paquette A, Hargreaves AL (2021) Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters, 24, 2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864

Sirén APK, Morelli TL (2020) Interactive range-limit theory (iRLT): An extension for predicting range shifts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89, 940–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13150

Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106

Summers JT, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2022) The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe

| The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair | Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen | <p>---This is a POST-STUDY manuscript for the PREREGISTRATION, which received in principle acceptance in 2020 from Dr. Sebastián González (reviewed by Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow; <a href="https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ec... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biogeography, Dispersal & Migration, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Preregistrations, Species distributions | Esther Sebastián González | | 2022-05-26 20:07:33 | View |

Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling

Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer

https://doi.org/10.1101/385120

Words matter: extensive misapplication of "non-invasive" in describing DNA sampling methods, and proposed clarifying terms

Recommended by Thomas Wilson Sappington based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The ability to successfully sequence trace quantities of environmental DNA (eDNA) has provided unprecedented opportunities to use genetic analyses to elucidate animal ecology, behavior, and population structure without affecting the behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal sampled. Hair associated with an animal track in the snow, the shed exoskeleton of an insect, or a swab of animal scat are all examples of non-invasive methods to collect eDNA. Despite the seemingly uncomplicated definition of "non-invasive" as proposed by Taberlet et al. [1], Lefort et al. [2] highlight that its appropriate application to sampling methods in practice is not so straightforward. For example, collecting scat left behind on the forest floor by a mammal could be invasive if feces is used by that species to mark territorial boundaries. Other collection strategies such as baited DNA traps to collect hair, capturing and handling an individual to swab or stimulate emission of a body fluid, or removal of a presumed non essential body part like a feather, fish scale, or even a leg from an insect are often described as "non-invasive" sampling methods. However, such methods cannot be considered truly non-invasive. At a minimum, attracting or capturing and handling an animal to obtain a DNA sample interrupts its normal behavioral routine, but additionally can cause both acute and long-lasting physiological and behavioral stress responses and other effects. Even invertebrates exhibit long-term hypersensitization after an injury, which manifests as heightened vigilance and enhanced escape responses [3-5].

Through an extensive analysis of 380 papers published from 2013-2018, Lefort et al. [2] document the widespread misapplication of the term "non-invasive" to methods used to sample DNA. An astonishing 58% of these papers employed the term incorrectly. A big part of the problem is that "non-invasive" is usually used by authors in the medical or veterinary sense of not breaking the skin or entering the body [6], rather than in the broader, ecological sense of Taberlet et al. [1]. The authors argue that correct use of the term matters, because it may lead naive readers – one can imagine students, policy makers, and the general public – to incorrectly assume a particular method is safe to use in a situation where disturbing the animal could affect experimental results or raise animal welfare concerns. Such assumptions can affect experimental design, as well as interpretations of one's own or others' data.

The importance of the Lefort et al. [2] paper lies in part on the authors' call for the research community to be much more careful when applying the term "non-invasive" to methods of DNA sampling. This call cannot be shrugged off as a minor problem in a few papers – as their literature review demonstrates, "non-invasive" is being applied incorrectly more often than not. The authors recognize that not all DNA sampling must be non-invasive to be useful or ethical. Examples include taking samples for DNA extraction from museum specimens, or opportunistically from carcasses of animals hunted either legally or seized by authorities from poachers. In many cases, there may be no viable non-invasive method to obtain DNA, but a researcher strives to collect samples using methods that, although they may involve taking a sample directly from the animal's body, do not disrupt, or only slightly disrupt behavior, fitness, or welfare of the animal. Thus, the other important contribution by Lefort et al. [2] is to propose the terms "non-disruptive" and "minimally-disruptive" to describe such sampling methods, which are not strictly non-invasive. While gray areas undoubtedly remain, as acknowledged by the authors, answering the call for correct use of "non-invasive" and applying the proposed new terms for certain types of invasive sampling with a focus on level of disruption, will go a long way in limiting misconceptions and misinterpretations caused by the current confusion in terminology.

References

[1] Taberlet P., Waits L. P. and Luikart G. 1999. Noninvasive genetic sampling: look before you leap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 323-327. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01637-7

[2] Lefort M.-C., Cruickshank R. H., Descovich K., Adams N. J., Barun A., Emami-Khoyi A., Ridden J., Smith V. R., Sprague R., Waterhouse B. R. and Boyer S. 2019. Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling. bioRxiv, 385120, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/385120

[3] Khuong T. M., Wang Q.-P., Manion J., Oyston L. J., Lau M.-T., Towler H., Lin Y. Q. and Neely G. G. 2019. Nerve injury drives a heightened state of vigilance and neuropathic sensitization in Drosophila. Science Advances 5: eaaw4099. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw4099

[4] Crook, R. J., Hanlon, R. T. and Walters, E. T. 2013. Squid have nociceptors that display widespread long-term sensitization and spontaneous activity after bodily injury. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(24), 10021-10026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0646-13.2013

[5] Walters E. T. 2018. Nociceptive biology of molluscs and arthropods: evolutionary clues about functions and mechanisms potentially related to pain. Frontiers in Physiololgy 9: doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01049

[6] Garshelis, D. L. 2006. On the allure of noninvasive genetic sampling-putting a face to the name. Ursus 17: 109-123. doi: 10.2192/1537-6176(2006)17[109:OTAONG]2.0.CO;2

| Blood, sweat and tears: a review of non-invasive DNA sampling | Marie-Caroline Lefort, Robert H Cruickshank, Kris Descovich, Nigel J Adams, Arijana Barun, Arsalan Emami-Khoyi, Johnaton Ridden, Victoria R Smith, Rowan Sprague, Benjamin Waterhouse, Stephane Boyer | <p>The use of DNA data is ubiquitous across animal sciences. DNA may be obtained from an organism for a myriad of reasons including identification and distinction between cryptic species, sex identification, comparisons of different morphocryptic ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Molecular ecology, Zoology | Thomas Wilson Sappington | | 2018-11-30 13:33:31 | View |

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics

F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux

https://doi.org/10.1101/640995

Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systems

Recommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

Conservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4].

The existence of SAR in patch-matrix systems has been confirmed in several studies, while the relative importance of SIR remains debated [2,5] and empirical evidence is mixed. For example, Thiele et al. [6] showed that connectivity effects are trait specific and more important to explain species richness of short-distant dispersers and of specialist species for which the matrix is less permeable. Some authors have also cautioned that the relative support for or against the existence of SIR may depend on methodological decisions related to connectivity metrics, patch classification, scaling decisions and sample size [7].

In this preprint, Laroche and colleagues [8] argue that methodological limits should be fully understood before questioning the validity of SIR in patch-matrix systems. In consequence, they used a virtual ecologist approach [9] to qualify different methodological aspects and derive good practice guidelines related to patch delineation, patch connectivity indices, and scaling of indices with species dispersal distance.

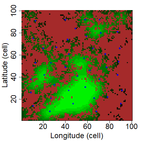

Laroche et al. [8] simulated spatially-explicit neutral meta-communities with up to 100 species in artificial fractal (patch-matrix) landscapes. Each habitat cell could hold up to 100 individuals. In each time step, some individuals died and were replaced by an individual from the regional species pool depending on relative local and regional abundance as well as dispersal distance to the nearest source habitat cell. Different scenarios were run with varying degrees of spatial autocorrelation in the fractal landscape (determining the clumpiness of habitat cells), the proportion of suitable habitat, and the species dispersal distances (with all species showing the same dispersal distance). Laroche and colleagues then sampled species richness in the simulated meta-communities, computed different local connectivity indices for the simulated landscapes (Buffer index with different radii, dIICflux index and dF index, and, finally, related species richness to connectivity.

The complex simulations allowed Laroche and colleagues [8] to test how methodological choices and landscape features may affect SIR. Overall, they found that patch delineation is crucial and should be fine enough to exclude potential within-patch dispersal limitations, and the scaling of the connectivity indices (in simplified words, the window of analyses) should be tailored to the dispersal distance of the species group. Of course, tuning the scaling parameters will be more complicated when dispersal distances vary across species but overall these results corroborate empirical findings that SIR effects are trait specific [6]. Additionally, the results by Laroche and colleagues [8] indicated that indices based on Euclidian rather than topological distance are more performant and that evidence of SIR is more likely if Buffer indices are highly variable between sampled patches.

Although the study is very technical due to the complex simulation approach and the different methods tested, I hope it will not only help guiding methodological choices but also inspire ecologists to further test or even revisit SIR (and SAR) hypotheses for different systems. Also, Laroche and colleagues propose many interesting avenues that could still be explored in this context, for example determining the optimal grid resolution for the patch delineation in empirical studies.

References

[1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

[2] Fahrig, L. (2013) Rethinking patch size and isolation effects: the habitat amount hypothesis. Journal of Biogeography, 40(9), 1649-1663. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12130

[3] Hanski, I., Zurita, G.A., Bellocq, M.I. and Rybicki J (2013) Species–fragmented area relationship. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., 110(31), 12715-12720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311491110

[4] Giladi, I., May, F., Ristow, M., Jeltsch, F. and Ziv, Y. (2014) Scale‐dependent species–area and species–isolation relationships: a review and a test study from a fragmented semi‐arid agro‐ecosystem. Journal of Biogeography, 41(6), 1055-1069. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12299

[5] Hodgson, J.A., Moilanen, A., Wintle, B.A. and Thomas, C.D. (2011) Habitat area, quality and connectivity: striking the balance for efficient conservation. Journal of Applied Ecology, 48(1), 148-152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01919.x

[6] Thiele, J., Kellner, S., Buchholz, S., and Schirmel, J. (2018) Connectivity or area: what drives plant species richness in habitat corridors? Landscape Ecology, 33, 173-181. doi: 10.1007/s10980-017-0606-8

[7] Vieira, M.V., Almeida-Gomes, M., Delciellos, A.C., Cerqueira, R. and Crouzeilles, R. (2018) Fair tests of the habitat amount hypothesis require appropriate metrics of patch isolation: An example with small mammals in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Biological Conservation, 226, 264-270. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.08.008

[8] Laroche, F., Balbi, M., Grébert, T., Jabot, F. and Archaux, F. (2020) Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics. bioRxiv, 640995, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/640995

[9] Zurell, D., Berger, U., Cabral, J.S., Jeltsch, F., Meynard, C.N., Münkemüller, T., Nehrbass, N., Pagel, J., Reineking, B., Schröder, B. and Grimm, V. (2010) The virtual ecologist approach: simulating data and observers. Oikos, 119(4), 622-635. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.18284.x

| Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View |

based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Yuval Zelnik and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers