Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Oct 2018

How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion.Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard 10.1101/273557Optimal foraging in a changing world: old questions, new perspectivesRecommended by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Frederick Adler, Andrew Higginson and 1 anonymous reviewer

Marginal value theorem (MVT) is an archetypal model discussed in every behavioural ecology textbook. Its popularity is largely explained but the fact that it is possible to solve it graphically (at least in its simplest form) with the minimal amount of equations, which is a sensible strategy for an introductory course in behavioural ecology [1]. Apart from this heuristic value, one may be tempted to disregard it as a naive toy model. After a burst of interest in the 70's and the 80's, the once vivid literature about optimal foraging theory (OFT) has lost its momentum [2]. Yet, OFT and MVT have remained an active field of research in the parasitoidologists community, mostly because the sampling strategy of a parasitoid in patches of hosts and its resulting fitness gain are straightforward to evaluate, which eases both experimental and theoretical investigations [3]. References [1] Fawcett, T. W. & Higginson, A. D. 2012 Heavy use of equations impedes communication among biologists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 11735–11739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205259109 | How optimal foragers should respond to habitat changes? On the consequences of habitat conversion. | Vincent Calcagno, Frederic Hamelin, Ludovic Mailleret, Frederic Grognard | The Marginal Value Theorem (MVT) provides a framework to predict how habitat modifications related to the distribution of resources over patches should impact the realized fitness of individuals and their optimal rate of movement (or patch residen... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont | 2018-03-05 10:42:11 | View | |

29 Sep 2023

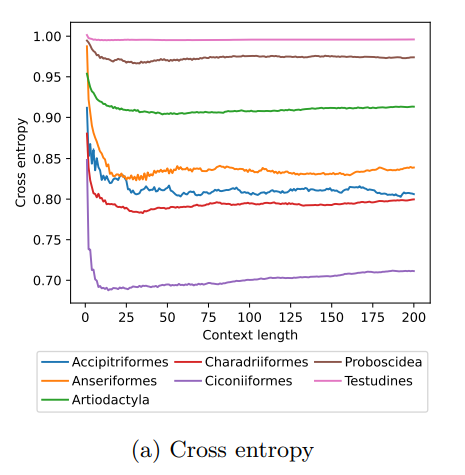

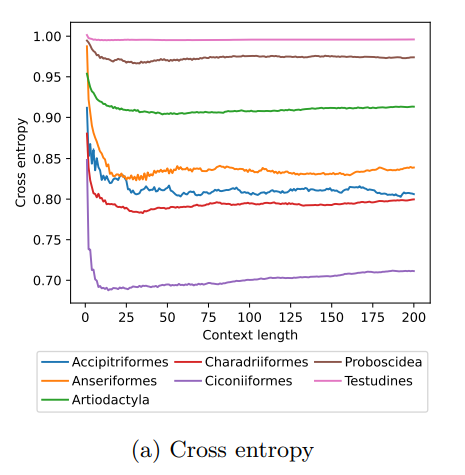

MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modellingOndřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.05.531080A deep learning model to unlock secrets of animal movement and behaviourRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

The study of animal movement is essential for understanding their behaviour and how ecological or global changes impact their routines [1]. Recent technological advancements have improved the collection of movement data [2], but limited statistical tools have hindered the analysis of such data [3–5]. Animal movement is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by internal knowledge and memory, which are challenging to observe directly [6,7]. Routine movement behaviours and the incorporation of memory into models remain understudied. Researchers have developed ‘MoveFormer’ [8], a deep learning-based model that predicts future movements based on past context, addressing these challenges and offering insights into the importance of different context lengths and information types. The model has been applied to a dataset of over 1,550 trajectories from various species, and the authors have made the MoveFormer source code available for further research. Inspired by the step-selection framework and efforts to quantify uncertainty in movement predictions, MoveFormer leverages deep learning, specifically the Transformer architecture, to encode trajectories and understand how past movements influence current and future ones – a critical question in movement ecology. The results indicate that integrating information from a few days to two or three weeks before the movement enhances predictions. The model also accounts for environmental predictors and offers insights into the factors influencing animal movements. Its potential impact extends to conservation, comparative analyses, and the generalisation of uncertainty-handling methods beyond ecology, with open-source code fostering collaboration and innovation in various scientific domains. Indeed, this method could be applied to analyse other kinds of movements, such as arm movements during tool use [9], pen movements, or eye movements during drawing [10], to better understand anticipation in actions and their intentionality. References 1. Méndez, V.; Campos, D.; Bartumeus, F. Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous Diffusion, Front Propagation and Random Searches; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-39009-8. | MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modelling | Ondřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus | <p style="text-align: justify;">The movement of animals is a central component of their behavioural strategies. Statistical tools for movement data analysis, however, have long been limited, and in particular, unable to account for past movement i... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Habitat selection | Cédric Sueur | 2023-03-22 16:32:14 | View | |

26 Mar 2019

Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity?Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_exploration.htmlProbing behaviors correlated with behavioral flexibilityRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Behavioral plasticity, which is a subset of phenotypic plasticity, is an important component of foraging, defense against predators, mating, and many other behaviors. More specifically, behavioral flexibility, in this study, captures how quickly individuals adapt to new circumstances. In cases where individuals disperse to new environments, which often occurs in range expansions, behavioral flexibility is likely crucial to the chance that individuals can establish in these environments. Thus, it is important to understand how best to measure behavioral flexibility and how measures of such flexibility might vary across individuals and behavioral contexts and with other measures of learning and problem solving. | Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity? | Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | This is a PREREGISTRATION. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific file we are submitting is g_exploration.Rmd, which is easily accessible at GitHub at https://github.com/cor... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2018-09-27 03:35:12 | View | ||

28 Aug 2023

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30JBehavioral changes in the rapid geographic expansion of the great-tailed grackleRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer

While many species' populations are declining, primarily due to human-related impacts (McKnee et al., 2014), certain species have thrived by utilizing human-influenced environments, leading to their population expansion (Muñoz & Real, 2006). In this context, the capacity to adapt and modify behaviors in response to new surroundings is believed to play a crucial role in facilitating species' spread to novel areas (Duckworth & Badyaev, 2007). For example, an increase in innovative behaviors within recently established communities could aid in discovering previously untapped food resources, while a decrease in exploration might reduce the likelihood of encountering dangers in unfamiliar territories (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016). To investigate the contribution of these behaviors to rapid range expansions, it is essential to directly measure and compare behaviors in various populations of the species. The study conducted by Logan et al. (2023) aims to comprehend the role of behavioral changes in the range expansion of great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). To achieve this, the researchers compared the prevalence of specific behaviors at both the expansion's edge and its middle. Great-tailed grackles were chosen as an excellent model due to their behavioral adaptability, rapid geographic expansion, and their association with human-modified environments. The authors carried out a series of experiments in captivity using wild-caught individuals, following a detailed protocol. The study successfully identified differences in two of the studied behavioral traits: persistence (individuals participated in a larger proportion of trials) and flexibility variance (a component of the species' behavioral flexibility, indicating a higher chance that at least some individuals in the population could be more flexible). Notably, individuals at the edge of the population exhibited higher values of persistence and flexibility, suggesting that these behavioral traits might be contributing factors to the species' expansion. Overall, the study by Logan et al. (2023) is an excellent example of the importance of behavioral flexibility and other related behaviors in the process of species' range expansion and the significance of studying these behaviors across different populations to gain a better understanding of their role in the expansion process. Finally, it is important to underline that this study is part of a pre-registration that received an In Principle Recommendation in PCI Ecology (Sebastián-González 2020) where objectives, methodology, and expected results were described in detail. The authors have identified any deviation from the original pre-registration and thoroughly explained the reasons for their deviations, which were very clear. References Duckworth, R. A., & Badyaev, A. V. (2007). Coupling of dispersal and aggression facilitates the rapid range expansion of a passerine bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(38), 15017-15022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706174104 Griffin, A.S., Guez, D., Federspiel, I., Diquelou, M., Lermite, F. (2016). Invading new environments: A mechanistic framework linking motor diversity and cognition to establishment success. Biological Invasions and Animal Behaviour, 26e46. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139939492.004 Logan, C. J., McCune, K., LeGrande-Rolls, C., Marfori, Z., Hubbard, J., Lukas, D. 2023. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30J McKee, J. K., Sciulli, P. W., Fooce, C. D., & Waite, T. A. (2004). Forecasting global biodiversity threats associated with human population growth. Biological Conservation, 115(1), 161-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00099-5 Muñoz, A. R., & Real, R. (2006). Assessing the potential range expansion of the exotic monk parakeet in Spain. Diversity and Distributions, 12(6), 656-665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2006.00272.x Sebastián González, E. (2020) The role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansion. Peer Community in Ecology, 100062. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100062. Reviewers: Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of species to rapidly expand their geographic range. Great-tailed grackles (<em>Quiscalus mexi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | 2023-04-12 11:00:42 | View | ||

12 Apr 2023

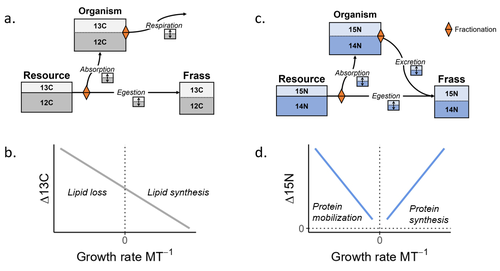

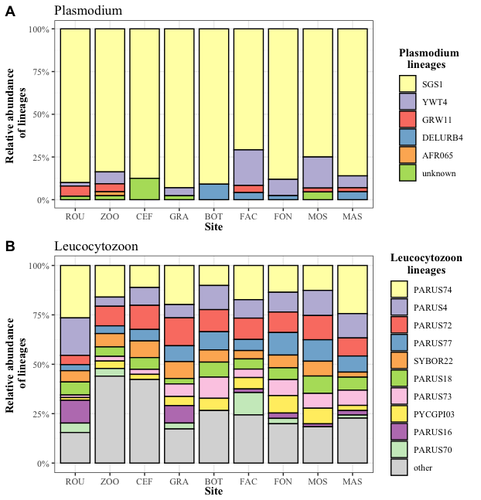

Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larvaSamuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573Refining our understanding how nutritional conditions affect 13C and 15N isotopic fractionation during ontogeny in a herbivorous insectRecommended by Gregor Kalinkat based on reviews by Anton Potapov and 1 anonymous reviewerUsing stable isotope fractionation to disentangle and understand the trophic positions of animals within the food webs they are embedded within has a long tradition in ecology (Post, 2002; Scheu, 2002). Recent years have seen increasing application of the method with several recent reviews summarizing past advancements in this field (e.g. Potapov et al., 2019; Quinby et al., 2020). In their new manuscript, Charberet and colleagues (2023) set out to refine our understanding of the processes that lead to nitrogen and carbon stable isotope fractionation by investigating how herbivorous insect larvae (specifically, the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis) respond to varying nutritional conditions (from starving to ad libitum feeding) in terms of stable isotopes enrichment. Though the underlying mechanisms have been experimentally investigated before in terrestrial invertebrates (e.g. in wolf spiders; Oelbermann & Scheu, 2002), the elegantly designed and adequately replicated experiments by Charberet and colleagues add new insights into this topic. Particularly, the authors provide support for the hypotheses that (A) 15N is disproportionately accumulated under fast growth rates (i.e. when fed ad libitum) and that (B) 13C is accumulated under low growth rates and starvation due to depletion of 13C-poor fat tissues. Applying this knowledge to field samples where feeding conditions are usually not known in detail is not straightforward, but the new findings could still help better interpretation of field data under specific conditions that make starvation for herbivores much more likely (e.g. droughts). Overall this study provides important methodological advancements for a better understanding of plant-herbivore interactions in a changing world. REFERENCES Charberet, S., Maria, A., Siaussat, D., Gounand, I., & Mathieu, J. (2023). Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573 Oelbermann, K., & Scheu, S. (2002). Stable Isotope Enrichment (δ 15N and δ 13C) in a Generalist Predator (Pardosa lugubris, Araneae: Lycosidae): Effects of Prey Quality. Oecologia, 130(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100813 Post, D. M. (2002). Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology, 83(3), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2 Potapov, A. M., Tiunov, A. V., & Scheu, S. (2019). Uncovering trophic positions and food resources of soil animals using bulk natural stable isotope composition. Biological Reviews, 94(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12434 Quinby, B. M., Creighton, J. C., & Flaherty, E. A. (2020). Stable isotope ecology in insects: A review. Ecological Entomology, 45(6), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12934 Scheu, S. (2002). The soil food web: Structure and perspectives. European Journal of Soil Biology, 38(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01117-7 | Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva | Samuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu | <p style="text-align: justify;">Isotopes are widely used in ecology to study food webs and physiology. The fractionation observed between trophic levels in nitrogen and carbon isotopes, explained by isotopic biochemical selectivity, is subject to ... |  | Experimental ecology, Food webs, Physiology | Gregor Kalinkat | 2022-11-16 15:23:31 | View | |

18 Dec 2020

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islandsManuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamicsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey

Polar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). References Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043 | Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands | Manuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault | <p>Aim Here, we aim to: (i) investigate the local effect of environmental and human-related factors on alien plant invasion in sub-Antarctic islands; (ii) explore the relationship between alien species features and their dependence on anthropogeni... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2020-07-21 21:13:08 | View | |

01 Mar 2024

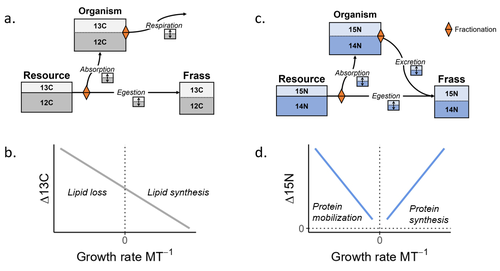

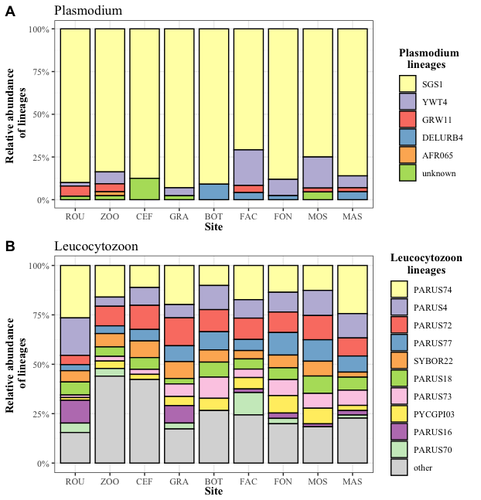

Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradientAude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263Exploring the Impact of Urbanization on Avian Malaria Dynamics in Great Tits: Insights from a Study Across Urban and Non-Urban EnvironmentsRecommended by Adrian Diaz based on reviews by Ana Paula Mansilla and 2 anonymous reviewersAcross the temporal expanse of history, the impact of human activities on global landscapes has manifested as a complex interplay of ecological alterations. From the advent of early agricultural practices to the successive waves of industrialization characterizing the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropogenic forces have exerted profound and enduring transformations upon Earth's ecosystems. Indeed, by 2017, more than 80% of the terrestrial biosphere was transformed by human populations and land use, and just 19% remains as wildlands (Ellis et al. 2021). Caizergues AE, Robira B, Perrier C, Jeanneau M, Berthomieu A, Perret S, Gandon S, Charmantier A (2023) Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient. bioRxiv, 2023.05.03.539263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.03.539263 Ellis EC, Gauthier N, Klein Goldewijk K, Bliege Bird R, Boivin N, Díaz S, Fuller DQ, Gill JL, Kaplan JO, Kingston N, Locke H, McMichael CNH, Ranco D, Rick TC, Shaw MR, Stephens L, Svenning JC, Watson JEM. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 27;118(17):e2023483118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023483118. Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x Reyes R, Ahn R, Thurber K, Burke TF (2013) Urbanization and Infectious Diseases: General Principles, Historical Perspectives, and Contemporary Challenges. Challenges Infect Dis 123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4496-1_4 | Cities as parasitic amplifiers? Malaria prevalence and diversity in great tits along an urbanization gradient | Aude E. Caizergues, Benjamin Robira, Charles Perrier, Melanie Jeanneau, Arnaud Berthomieu, Samuel Perret, Sylvain Gandon, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">Urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon that modifies the environment. By affecting the reservoirs of pathogens and the body and immune conditions of hosts, urbanization alters the epidemiological dynamics and divers... |  | Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Human impact | Adrian Diaz | Anonymous, Gauthier Dobigny, Ana Paula Mansilla | 2023-09-11 20:24:44 | View |

14 Nov 2022

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture modelsCécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bearRecommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated. Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008. Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007 Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135. Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025 Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719 | Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models | Cécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez | <p>Estimating the size of small populations of large mammals can be achieved via censuses, or complete counts, of recognizable individuals detected over a time period: minimum detected (population) size (MDS). However, as a population grows larger... |  | Conservation biology, Demography, Population ecology | Nicolas BECH | 2022-01-20 10:49:59 | View | |

06 May 2021

Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changesThibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021A lack of clear dietary differences between ontogenetic stages of invasive slippersnails provides important insights into resource use and potential inter- and intra-specific competitionRecommended by Matthew Bracken based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe slippersnail (Crepidula fornicata), originally from the eastern coast of North America, has invaded European coastlines from Norway to the Mediterranean Sea [1]. This species is capable of achieving incredibly high densities (up to several thousand individuals per square meter) and likely has major impacts on a variety of community- and ecosystem-level processes, including alteration of carbon and nitrogen fluxes and competition with native suspension feeders [2]. Given this potential for competition, it is important to understand the diet of C. fornicata and its potential overlap with native species. However, previous research on the diet of C. fornicata and related species suggests that the types of food consumed may change with age [3, 4]. This species has an unusual reproductive strategy. It is a sequential hermaphrodite, which begins life as a somewhat mobile male but eventually slows down to become sessile. Sessile individuals form stacks of up to 10 or more individuals, with larger individuals on the bottom of the stack, and decreasingly smaller individuals piled on top. Snails at the bottom of the stack are female, whereas snails at the top of the stack are male; when the females die, the largest males become female [5]. Thus, understanding these potential ontogenetic dietary shifts has implications for both intraspecific (juvenile vs. male vs. female) and interspecific competition associated with an abundant, invasive species. To this end, Androuin and colleagues evaluated the stable-isotope (d13C and d15N) and fatty-acid profiles of food sources and different life-history stages of C. fornicata [6]. Based on previous work highlighting the potential for life-history changes in the diet of this species [3,4], they hypothesized that C. fornicata would shift its diet as it aged and predicted that this shift would be reflected in changes in its stable-isotope and fatty-acid profiles. The authors found that potential food sources (biofilm, suspended particulate organic matter, and superficial sedimentary organic matter) differed substantially in both stable-isotope and fatty-acid signatures. However, whereas fatty-acid profiles changed substantially with age, there was no shift in the stable-isotope signatures. Because stable-isotope differences between food sources were not reflected in differences between life-history stages, the authors conservatively concluded that there was insufficient evidence for a diet shift with age. The ontogenetic shifts in fatty-acid profiles were intriguing, but the authors suggested that these reflected age-related physiological changes rather than changes in diet. The authors’ work highlights the need to consider potential changes in the roles of invasive species with age, especially when evaluating interactions with native species. In this case, C. fornicata consumed a variety of food sources, including both benthic and particulate organic matter, regardless of age. The carbon stable-isotope signature of C. fornicata overlaps with those of several native suspension- and deposit-feeding species in the region [7], suggesting the possibility of resource competition, especially given the high abundances of this invader. This contribution demonstrates the potential difficulty of characterizing the impacts of an abundant invasive species with a complex life-history strategy. Like many invasive species, C. fornicata appears to be a dietary generalist, which likely contributes to its success in establishing and thriving in a variety of locations [8].

References [1] Blanchard M (1997) Spread of the slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L. 1758) in Europe. Current state dans consequences. Scientia Marina, 61, 109–118. Open Access version : https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00423/53398/54271.pdf [2] Martin S, Thouzeau G, Chauvaud L, Jean F, Guérin L, Clavier J (2006) Respiration, calcification, and excretion of the invasive slipper limpet, Crepidula fornicata L.: Implications for carbon, carbonate, and nitrogen fluxes in affected areas. Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 1996–2007. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.1996 [3] Navarro JM, Chaparro OR (2002) Grazing–filtration as feeding mechanisms in motile specimens of Crepidula fecunda (Gastropoda: Calyptraeidae). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 270, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00013-8 [4] Yee AK, Padilla DK (2015) Allometric Scaling of the Radula in the Atlantic Slippersnail Crepidula fornicata. Journal of Shellfish Research, 34, 903–907. https://doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0320 [5] Collin R (1995) Sex, Size, and Position: A Test of Models Predicting Size at Sex Change in the Protandrous Gastropod Crepidula fornicata. The American Naturalist, 146, 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/285826 [6] Androuin T, Dubois SF, Hubas C, Lefebvre G, Grand FL, Schaal G, Carlier A (2021) Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.229021, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021 [7] Dauby P, Khomsi A, Bouquegneau J-M (1998) Trophic Relationships within Intertidal Communities of the Brittany Coasts: A Stable Carbon Isotope Analysis. Journal of Coastal Research, 14, 1202–1212. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4298880 [8] Machovsky-Capuska GE, Senior AM, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D (2016) The Multidimensional Nutritional Niche. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 31, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.009

| Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes | Thibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata is a common and widespread invasive gregarious species along the European coast. Among its life-history traits, well-documented ontogenic changes in behavior (i.e., motile male... |  | Food webs, Life history, Marine ecology | Matthew Bracken | 2020-08-01 23:55:57 | View | |

11 Mar 2021

Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheriesEric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905“Hidden” natural selection and the evolution of body size in harvested stocksRecommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi and 1 anonymous reviewerHumans are exploiting biological resources since thousands of years. Exploitation of biological resources has become particularly intense since the beginning of the 20th century and the steep increase in the worldwide human population size. Marine and freshwater fishes are not exception to that rule, and they have been (and continue to be) strongly harvested as a source of proteins for humans. For some species, fishery has been so intense that natural stocks have virtually collapsed in only a few decades. The worst example begin that of the Northwest Atlantic cod that has declined by more than 95% of its historical biomasses in only 20-30 years of intensive exploitation (Frank et al. 2005). These rapid and steep changes in biomasses have huge impacts on the entire ecosystems since species targeted by fisheries are often at the top of trophic chains (Frank et al. 2005). Beyond demographic impacts, fisheries also have evolutionary impacts on populations, which can also indirectly alter ecosystems (Uusi-Heikkilä et al. 2015; Palkovacs et al. 2018). Fishermen generally focus on the largest specimens, and hence exert a strong selective pressure against these largest fish (which is called “harvest selection”). There is now ample evidence that harvest selection can lead to rapid evolutionary changes in natural populations toward small individuals (Kuparinen & Festa-Bianchet 2017). These evolutionary changes are of course undesirable from a human perspective, and have attracted many scientific questions. Nonetheless, the consequence of harvest selection is not always observable in natural populations, and there are cases in which no phenotypic change (or on the contrary an increase in mean body size) has been observed after intense harvest pressures. In a conceptual Essay, Edeline and Loeuille (Edeline & Loeuille 2020) propose novel ideas to explain why the evolutionary consequences of harvest selection can be so diverse, and how a cross talk between ecological and evolutionary dynamics can explain patterns observed in natural stocks. The general and novel concept proposed by Edeline and Loeuille is actually as old as Darwin’s book; The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It is based on the simple idea that natural selection acting on harvested populations can actually be strong, and counter-balance (or on the contrary reinforce) the evolutionary consequence of harvest selection. Although simple, the idea that natural and harvest selection are jointly shaping contemporary evolution of exploited populations lead to various and sometimes complex scenarios that can (i) explain unresolved empirical patterns and (ii) refine predictions regarding the long-term viability of exploited populations. The Edeline and Loeuille’s crafty inspiration is that natural selection acting on exploited populations is itself an indirect consequence of harvest (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). They suggest that, by modifying the size structure of populations (a key parameter for ecological interactions), harvest indirectly alters interactions between populations and their biotic environment through competition and predation, which changes the ecological theatre and hence the selective pressures acting back to populations. They named this process “size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedback loops” and develop several scenarios in which these feedback loops ultimately deviate the evolutionary outcome of harvest selection from expectation. The scenarios they explore are based on strong theoretical knowledge, and range from simple ones in which a single species (the harvest species) is evolving to more complex (and realistic) ones in which multiple (e.g. the harvest species and its prey) species are co-evolving. I will not come into the details of each scenario here, and I will let the readers (re-)discovering the complex beauty of biological life and natural selection. Nonetheless, I will emphasize the importance of considering these eco-evolutionary processes altogether to fully grasp the response of exploited populations. Edeline and Loeuille convincingly demonstrate that reduced body size due to harvest selection is obviously not the only response of exploited fish populations when natural selection is jointly considered (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). On the contrary, they show that –under some realistic ecological circumstances relaxing exploitative competition due to reduced population densities- natural selection can act antagonistically, and hence favour stable body size in exploited populations. Although this seems further desirable from a human perspective than a downsizing of exploited populations, it is actually mere window dressing as Edeline and Loeuille further showed that this response is accompanied by an erosion of the evolvability –and hence a lowest probability of long-term persistence- of these exploited populations. Humans, by exploiting biological resources, are breaking the relative equilibrium of complex entities, and the response of populations to this disturbance is itself often complex and heterogeneous. In this Essay, Edeline and Loeuille provide –under simple terms- the theoretical and conceptual bases required to improve predictions regarding the evolutionary responses of natural populations to exploitation by humans (Edeline & Loeuille 2020). An important next step will be to generate data and methods allowing confronting the empirical reality to these novel concepts (e.g. (Monk et al. 2021), so as to identify the most likely evolutionary scenarios sustaining biological responses of exploited populations, and hence to set the best management plans for the long-term sustainability of these populations. References Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. John Murray, London. Edeline, E. & Loeuille, N. (2021) Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries. bioRxiv, 2020.04.03.022905, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.022905 Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J. S. & Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem. Science, 308, 1621–1623. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113075 Kuparinen, A. & Festa-Bianchet, M. (2017). Harvest-induced evolution: insights from aquatic and terrestrial systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 372, 20160036. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0036 Monk, C.T., Bekkevold, D., Klefoth, T., Pagel, T., Palmer, M. & Arlinghaus, R. (2021). The battle between harvest and natural selection creates small and shy fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2009451118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009451118 Palkovacs, E.P., Moritsch, M.M., Contolini, G.M. & Pelletier, F. (2018). Ecology of harvest-driven trait changes and implications for ecosystem management. Front. Ecol. Environ., 16, 20–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1743 Uusi-Heikkilä, S., Whiteley, A.R., Kuparinen, A., Matsumura, S., Venturelli, P.A., Wolter, C., et al. (2015). The evolutionary legacy of size-selective harvesting extends from genes to populations. Evol. Appl., 8, 597–620. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12268 | Size-dependent eco-evolutionary feedbacks in fisheries | Eric Edeline and Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Harvesting may drive body downsizing along with population declines and decreased harvesting yields. These changes are commonly construed as direct consequences of harvest selection, where small-bodied, early-reproducing individuals are immedia... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Competition, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Food webs, Interaction networks, Life history, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2020-04-03 16:14:05 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle