Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors▲ | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View | |

12 Mar 2023

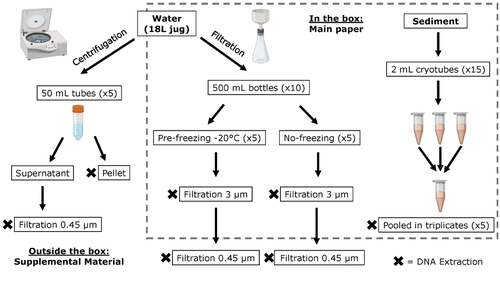

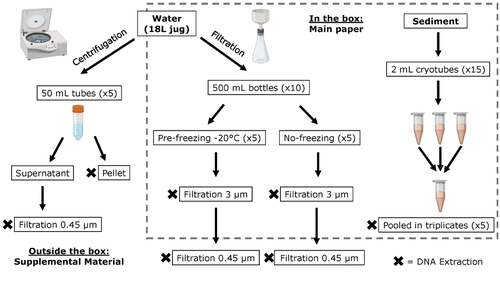

Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities.Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388Processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters from coastal lagoonsRecommended by Claudia Piccini based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Rutger De WitCoastal lagoons are among the most productive natural ecosystems on Earth. These relatively closed basins are important habitats and nursery for endemic and endangered species and are extremely vulnerable to nutrient input from the surrounding catchment; therefore, they are highly susceptible to anthropogenic influence, pollution and invasion (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). In general, coastal lagoons exhibit great spatial and temporal variability in their physicochemical water characteristics due to the sporadic mixing of freshwater with marine influx. One of the alternatives for monitoring communities or target species in aquatic ecosystems is the environmental DNA (eDNA), since overcomes some limitations from traditional methods and enables the investigation of multiple species from a single sample (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). In coastal lagoons, where the water turbidity is highly variable, there is a major challenge for monitoring the eDNA because filtering turbid water to obtain the eDNA is problematic (filters get rapidly clogged, there is organic and inorganic matter accumulation, etc.). The study by Turba et al. (2023) analyzes different ways of dealing with eDNA sampling and processing in turbid waters and sediments of coastal lagoons, and offers guidelines to obtain unbiased results from the subsequent sequencing using 12S (fish) and 16S (Bacteria and Archaea) universal primers. They analyzed the effect on taxa detection of: i) freezing or not prior to filtering; ii) freezing prior to centrifugation to obtain a sample pellet; and iii) using frozen sediment samples as a proxy of what happens in the water. The authors propose these different alternatives (freeze, do not freeze, sediment sampling) because they consider that they are the easiest to carry out. They found that freezing before filtering using a 3 µm pore size filter had no effects on community composition for either primer, and therefore it is a worthwhile approach for comparison of fish, bacteria and archaea in this kind of system. However, significantly different bacterial community composition was found for sediment compared to water samples. Also, in sediment samples the replicates showed to be more heterogeneous, so the authors suggest increasing the number of replicates when using sediment samples. Something that could be a concern with the study is that the rarefaction curves based on sequencing effort for each protocol did not saturate in any case, this being especially evident in sediment samples. The authors were aware of this, used the slopes obtained from each curve as a measure of comparison between samples and considering that the sequencing depth did not meet their expectations, they managed to achieve their goal and to determine which protocol is the most promising for eDNA monitoring in coastal lagoons. Although there are details that could be adjusted in relation to this item, I consider that the approach is promising for this type of turbid system. References Pérez-Ruzafa A, Campillo S, Fernández-Palacios JM, García-Lacunza A, García-Oliva M, Ibañez H, Navarro-Martínez PC, Pérez-Marcos M, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Quispe-Becerra JI, Sala-Mirete A, Sánchez O, Marcos C (2019) Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00026 Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 Turba R, Thai GH, Jacobs DK (2023) Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.495388, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388 | Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. | Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are an important habitat for endemic and threatened species in California that have suffered impacts from urbanization and increased drought. Environmental DNA has been promoted as a way to aid in th... |  | Biodiversity, Community genetics, Conservation biology, Freshwater ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Claudia Piccini | David Murray-Stoker | 2022-06-20 20:31:51 | View |

02 Jan 2024

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

29 Mar 2021

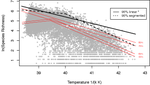

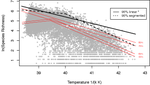

Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variationRicardo A. Segovia https://doi.org/10.1101/836338New light on the baseline importance of temperature for the origin of geographic species richness gradientsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewersWhether environmental conditions –in particular energy and water availability– are sufficient to account for species richness gradients (e.g. Currie 1991), or the effects of other biotic and historical or regional factors need to be considered as well (e.g. Ricklefs 1987), was the subject of debate during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Francis & Currie 2003; Hawkins et al. 2003, 2006; Currie et al. 2004; Ricklefs 2004). The metabolic theory of ecology (Brown et al. 2004) provided a solid and well-rooted theoretical support for the preponderance of energy as the main driver for richness variations. As any good piece of theory, it provided testable predictions about the sign and shape (i.e. slope) of the relationship between temperature –a key aspect of ambient energy– and species richness. However, these predictions were not supported by empirical evaluations (e.g. Kreft & Jetz 2007; Algar et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 2007a), as the effects of a myriad of other environmental gradients, regional factors and evolutionary processes result in a wide variety of richness–temperature responses across different groups and regions (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Hortal et al. 2008). So, in a textbook example of how good theoretical work helps advancing science even if proves to be (partially) wrong, the evaluation of this aspect of the metabolic theory of ecology led to current understanding that, while species richness does respond to current climatic conditions, many other ecological, evolutionary and historical factors do modify such response across scales (see, e.g., Ricklefs 2008; Hawkins 2008; D’Amen et al. 2017). And the kinetic model linking mean annual temperature and species richness (Allen et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2004) was put aside as being, perhaps, another piece of the puzzle of the origin of current diversity gradients. Segovia (2021) puts together an elegant way of reinvigorating this part of the metabolic theory of ecology. He uses quantile regressions to model just the upper parts of the relationship between species richness and mean annual temperature, rather than modelling its central tendency through the classical linear regression family of methods –as was done in the past. This assumes that the baseline effect of ambient energy does produce the negative linear relationship between richness and temperature predicted by the kinetic model (Allen et al. 2002), but also that this effect only poses an upper limit for species richness, and the effects of other factors may result in lower levels of species co-occurrence, thus producing a triangular rather than linear relationship. The results of Segovia’s simple and elegant analytical design show unequivocally that the predictions of the kinetic model become progressively more explanatory towards the upper quartiles of the relationship between species richness and temperature along over 10,000 tree local inventories throughout the Americas, reaching over 70% of explanatory power for the upper 5% of the relationship (i.e. the 95% quantile). This confirms to a large extent his reformulation of the predictions of the kinetic model. Further, the neat study from Segovia (2021) also provides evidence confirming that the well-known spatial non-stationarity in the richness–temperature relationship (see Cassemiro et al. 2007) also applies to its upper-bound segment. Both the explanatory power and the slope of the relationship in the 95% upper quantile vary widely between biomes, reaching values similar to the predictions of the kinetic model only in cold temperate environments –precisely where temperature becomes more important than water availability as a constrain to plant life (O’Brien 1998; Hawkins et al. 2003). Part of these variations are indeed related with changes in water deficit and number of frost days along the XXth Century, as shown by the residuals of this paper (Segovia 2021) and a more detailed separate study (Segovia et al. 2020). This pinpoints the importance of the relative balance between water and energy as two of the main climatic factors constraining species diversity gradients, confirming the value of hypotheses that date back to Humboldt’s work (see Hawkins 2001, 2008). There is however a significant amount of unexplained variation in Segovia’s analyses, in particular in the progressive departure of the predictions of the kinetic model as we move towards the tropics, or downwards along the lower quantiles of the richness–temperature relationship. This calls for a deeper exploration of the factors that modify the baseline relationship between richness and energy, opening a new avenue for the macroecological investigation of how different forces and processes shape up geographical diversity gradients beyond the mere energetic constrains imposed by the basal limitations of multicellular life on Earth. References Algar, A.C., Kerr, J.T. and Currie, D.J. (2007) A test of Metabolic Theory as the mechanism underlying broad-scale species-richness gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 170-178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00275.x Allen, A.P., Brown, J.H. and Gillooly, J.F. (2002) Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science, 297, 1545-1548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072380 Brown, J.H., Gillooly, J.F., Allen, A.P., Savage, V.M. and West, G.B. (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology, 85, 1771-1789. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-9000 Cassemiro, F.A.d.S., Barreto, B.d.S., Rangel, T.F.L.V.B. and Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. (2007) Non-stationarity, diversity gradients and the metabolic theory of ecology. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 820-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00332.x Currie, D.J. (1991) Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist, 137, 27-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/285144 Currie, D.J., Mittelbach, G.G., Cornell, H.V., Field, R., Guegan, J.-F., Hawkins, B.A., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2004) Predictions and tests of climate-based hypotheses of broad-scale variation in taxonomic richness. Ecology Letters, 7, 1121-1134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00671.x D'Amen, M., Rahbek, C., Zimmermann, N.E. and Guisan, A. (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Francis, A.P. and Currie, D.J. (2003) A globally consistent richness-climate relationship for Angiosperms. American Naturalist, 161, 523-536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/368223 Hawkins, B.A. (2001) Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8 Hawkins, B.A. (2008) Recent progress toward understanding the global diversity gradient. IBS Newsletter, 6.1, 5-8. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr2k1dd Hawkins, B.A., Field, R., Cornell, H.V., Currie, D.J., Guégan, J.-F., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Mittelbach, G.G., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E., Porter, E.E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2003) Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology, 84, 3105-3117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8006 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Jaramillo, C.A. and Soeller, S.A. (2006) Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 770-780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01452.x Hawkins, B.A., Albuquerque, F.S., Araújo, M.B., Beck, J., Bini, L.M., Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J., Castro Parga, I., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Ferrer-Castán, D., Field, R., Gómez, J.F., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Kitching, I.J., León-Cortés, J.L., et al. (2007a) A global evaluation of metabolic theory as an explanation for terrestrial species richness gradients. Ecology, 88, 1877-1888. doi:10.1890/06-1444.1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1444.1 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Bini, L.M., Araújo, M.B., Field, R., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Rahbek, C., Rodríguez, M.Á. and Sanders, N.J. (2007b) Metabolic theory and diversity gradients: Where do we go from here? Ecology, 88, 1898–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-2141.1 Hortal, J., Rodríguez, J., Nieto-Díaz, M. and Lobo, J.M. (2008) Regional and environmental effects on the species richness of mammal assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 35, 1202–1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01850.x Kreft, H. and Jetz, W. (2007) Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104, 5925-5930. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608361104 O'Brien, E. (1998) Water-energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 379-398. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x Ricklefs, R.E. (1987) Community diversity: Relative roles of local and regional processes. Science, 235, 167-171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4785.167 Ricklefs, R.E. (2004) A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 7, 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00554.x Ricklefs, R.E. (2008) Disintegration of the ecological community. American Naturalist, 172, 741-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/593002 Segovia, R.A. (2021) Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation. bioRxiv, 836338, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/836338 Segovia, R.A., Pennington, R.T., Baker, T.R., Coelho de Souza, F., Neves, D.M., Davis, C.C., Armesto, J.J., Olivera-Filho, A.T. and Dexter, K.G. (2020) Freezing and water availability structure the evolutionary diversity of trees across the Americas. Science Advances, 6, eaaz5373. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5373 | Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation | Ricardo A. Segovia | <p>The kinetic hypothesis of biodiversity proposes that temperature is the main driver of variation in species richness, given its exponential effect on biological activity and, potentially, on rates of diversification. However, limited support fo... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Botany, Macroecology, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2019-11-10 20:56:40 | View | |

12 Aug 2021

A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm callSamantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5Does the active vocabulary in Great-tailed Grackles supports their range expansion? New study will find outRecommended by Jan Oliver Engler based on reviews by Guillermo Fandos and 2 anonymous reviewersAlarm calls are an important acoustic signal that can decide the life or death of an individual. Many birds are able to vary their alarm calls to provide more accurate information on e.g. urgency or even the type of a threatening predator. According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis, the habitat plays an important role too in how acoustic patterns get transmitted. This is of particular interest for range-expanding species that will face new environmental conditions along the leading edge. One could hypothesize that the alarm call repertoire of a species could increase in newly founded ranges to incorporate new habitats and threats individuals might face. Hence selection for a larger active vocabulary might be beneficial for new colonizers. Using the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a model species, Samantha Bowser from Arizona State University and Maggie MacPherson from Louisiana State University want to find out exactly that. The Great-Tailed Grackle is an appropriate species given its high vocal diversity. Also, the species consists of different subspecies that show range expansions along the northern range edge yet to a varying degree. Using vocal experiments and field recordings the researchers have a high potential to understand more about the acoustic adaptation hypothesis within a range dynamic process. Over the course of this assessment, the authors incorporated the comments made by two reviewers into a strong revision of their research plans. With that being said, the few additional comments made by one of the initial reviewers round up the current stage this interesting research project is in. To this end, I can only fully recommend the revised research plan and am much looking forward to the outcomes from the author’s experiments, modeling, and field data. With the suggestions being made at such an early stage I firmly believe that the final outcome will be highly interesting not only to an ornithological readership but to every ecologist and biogeographer interested in drivers of range dynamic processes. References Bowser, S., MacPherson, M. (2021). A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call. In principle recommendation by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5. Version 3 | A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call | Samantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson | <p>The acoustic adaptation hypothesis posits that animal sounds are influenced by the habitat properties that shape acoustic constraints (Ey and Fischer 2009, Morton 2015, Sueur and Farina 2015).Alarm calls are expected to signal important habitat... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Coexistence, Dispersal & Migration, Habitat selection, Landscape ecology | Jan Oliver Engler | Darius Stiels, Anonymous | 2020-12-01 18:11:02 | View |

10 Oct 2018

Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence dataSamuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea https://doi.org/10.1101/256586Combining epidemiological models with statistical inference can detect parasite interactionsRecommended by Dustin Brisson based on reviews by Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne and 1 anonymous reviewerThere are several important topics in the study of infectious diseases that have not been well explored due to technical difficulties. One such topic is pursued by Alizon et al. in “Modelling coinfections to detect within-host interactions from genotype combination prevalences” [1]. Both theory and several important examples have demonstrated that interactions among co-infecting strains can have outsized impacts on disease outcomes, transmission dynamics, and epidemiology. Unfortunately, empirical data on pathogen interactions and their outcomes is often correlational making results difficult to decipher. References [1] Alizon, S., Murall, C.L., Saulnier, E., & Sofonea, M.T. (2018). Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data. bioRxiv, 256586, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/256586 | Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data | Samuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea | <p>Parasite genetic diversity can provide information on disease transmission dynamics but most methods ignore the exact combinations of genotypes in infections. We introduce and validate a new method that combines explicit epidemiological modelli... |  | Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Statistical ecology | Dustin Brisson | Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne | 2018-02-01 09:23:26 | View |

12 Apr 2023

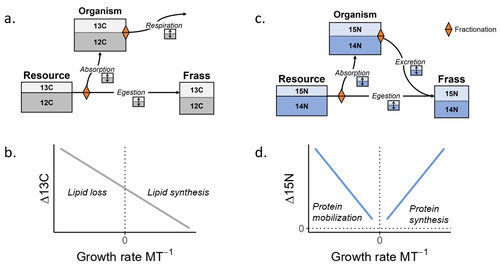

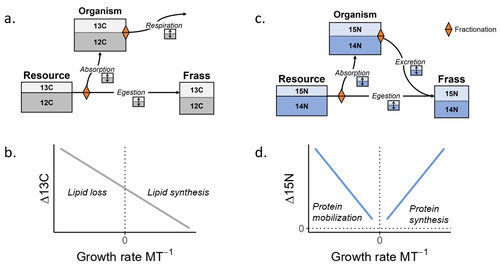

Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larvaSamuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573Refining our understanding how nutritional conditions affect 13C and 15N isotopic fractionation during ontogeny in a herbivorous insectRecommended by Gregor Kalinkat based on reviews by Anton Potapov and 1 anonymous reviewerUsing stable isotope fractionation to disentangle and understand the trophic positions of animals within the food webs they are embedded within has a long tradition in ecology (Post, 2002; Scheu, 2002). Recent years have seen increasing application of the method with several recent reviews summarizing past advancements in this field (e.g. Potapov et al., 2019; Quinby et al., 2020). In their new manuscript, Charberet and colleagues (2023) set out to refine our understanding of the processes that lead to nitrogen and carbon stable isotope fractionation by investigating how herbivorous insect larvae (specifically, the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis) respond to varying nutritional conditions (from starving to ad libitum feeding) in terms of stable isotopes enrichment. Though the underlying mechanisms have been experimentally investigated before in terrestrial invertebrates (e.g. in wolf spiders; Oelbermann & Scheu, 2002), the elegantly designed and adequately replicated experiments by Charberet and colleagues add new insights into this topic. Particularly, the authors provide support for the hypotheses that (A) 15N is disproportionately accumulated under fast growth rates (i.e. when fed ad libitum) and that (B) 13C is accumulated under low growth rates and starvation due to depletion of 13C-poor fat tissues. Applying this knowledge to field samples where feeding conditions are usually not known in detail is not straightforward, but the new findings could still help better interpretation of field data under specific conditions that make starvation for herbivores much more likely (e.g. droughts). Overall this study provides important methodological advancements for a better understanding of plant-herbivore interactions in a changing world. REFERENCES Charberet, S., Maria, A., Siaussat, D., Gounand, I., & Mathieu, J. (2023). Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573 Oelbermann, K., & Scheu, S. (2002). Stable Isotope Enrichment (δ 15N and δ 13C) in a Generalist Predator (Pardosa lugubris, Araneae: Lycosidae): Effects of Prey Quality. Oecologia, 130(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100813 Post, D. M. (2002). Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology, 83(3), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2 Potapov, A. M., Tiunov, A. V., & Scheu, S. (2019). Uncovering trophic positions and food resources of soil animals using bulk natural stable isotope composition. Biological Reviews, 94(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12434 Quinby, B. M., Creighton, J. C., & Flaherty, E. A. (2020). Stable isotope ecology in insects: A review. Ecological Entomology, 45(6), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12934 Scheu, S. (2002). The soil food web: Structure and perspectives. European Journal of Soil Biology, 38(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01117-7 | Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva | Samuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu | <p style="text-align: justify;">Isotopes are widely used in ecology to study food webs and physiology. The fractionation observed between trophic levels in nitrogen and carbon isotopes, explained by isotopic biochemical selectivity, is subject to ... |  | Experimental ecology, Food webs, Physiology | Gregor Kalinkat | 2022-11-16 15:23:31 | View | |

16 Oct 2018

Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus)Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4How empirical sciences may improve livestock welfare and help their managementRecommended by Marie Charpentier based on reviews by Alecia CARTER and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding how livestock management is a source of social stress and disturbances for cattle is an important question with potential applications for animal welfare programs and sustainable development. In their article, Sosa and colleagues [1] first propose to evaluate the effects of individual characteristics on dyadic social relationships and on the social dynamics of four groups of cattle. Using network analyses, the authors provide an interesting and complete picture of dyadic interactions among groupmates. Although shown elsewhere, the authors demonstrate that individuals that are close in age and close in rank form stronger dyadic associations than other pairs. Second, the authors take advantage of some transfers of animals between groups -for management purposes- to assess how these transfers affect the social dynamics of groupmates. Their central finding is that the identity of transferred animals is a key-point. In particular, removing offspring strongly destabilizes the social relationships of mothers while adding a bull into a group also profoundly impacts female-female social relationships, as social networks before and after transfer of these key-animals are completely different. In addition, individuals, especially the young ones, that are transferred without familiar conspecifics take more time to socialize with their new group members than individuals transferred with familiar groupmates, generating a potential source of stress. Interestingly, the authors end up their article with some thoughts on the implications of their findings for animal welfare and ethics. This study provides additional evidence that empirical science has a major role to play in providing recommendations regarding societal questions such as livestock management and animal wellbeing. References [1] Sosa, S., Pelé, M., Debergue, E., Kuntz, C., Keller, B., Robic, F., Siegwalt-Baudin, F., Richer, C., Ramos, A., & Sueur C. (2018). Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus). arXiv:1805.11553v4 [q-bio.PE] peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4 | Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus) | Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur | The sociality of cattle facilitates the maintenance of herd cohesion and synchronisation, making these species the ideal choice for domestication as livestock for humans. However, livestock populations are not self-regulated, and farmers transfer ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure | Marie Charpentier | 2018-05-30 14:05:39 | View | ||

14 Dec 2022

The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore dietSébastien Ibanez, Arnaud Foulquier, Charles Brun, Marie-Pascale Colace, Gabin Piton, Lionel Bernard, Christiane Gallet, Jean-Christophe Clément https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.04.497718Complex interactions between ecosystem productivity and herbivore diets lead to non-predicted effects on nutrient cyclingRecommended by Sébastien Barot based on reviews by Manuel Blouin and Tord Ranheim SveenThe authors present a study typical of the field of belowground-aboveground interactions [1]. This framework has been extremely fruitful since the beginning of 2000s [2]. It has also contributed to bridge the gap between soil ecology and the rest of ecology [3]. The study also pertains to the rich field on the impacts of herbivores on soil functioning [4]. The study more precisely tested during two years the effect on nutrient cycling of the interaction between the type of grassland (along a gradient of biomass productivity) and the diet of the community of insect herbivores (5 treatments manipulating the grasshopper community on 1 m2 plots, with a gradient from no grasshopper to grasshoppers either specialized on forbs or grasses). What seems extremely interesting is that the study is based on a rigorous hypothesis-testing approach. They compare the predictions of two frameworks: (1) The “productivity model” predicts that in productive ecosystems herbivores consume a high percentage of the net primary production thus accelerating nutrient cycling. (2) The “diet model” distinguishes herbivores consuming exploitative plants from those eating conservative plants. The former (later) type of herbivores favours conservative (exploitative) plants therefore decelerating (accelerating) nutrient cycling. Interestingly, the two frameworks have similar predictions (and symmetrically opposite predictions) in two cases out of four combinations between ecosystem productivities and types of diet (see Table 1). An other merit of the study is to combine in a rather comprehensive way all the necessary measurements to test these frameworks in combination: grasshopper diet, soil properties, characteristics of the soil microbial community, plant traits, vegetation survey and plant biomass. The results were in contradiction with the ‘‘diet model’’: microbial properties and nitrogen cycling did not depend on grasshopper diet. The productivity of the grasslands did impact nutrient cycling but not in the direction predicted by the “productivity model”: productive grasslands hosted exploitative plants that depleted N resources in the soil and microbes producing few extracellular enzymes, which led to a lower potential N mineralization and a deceleration of nutrient cycling. Because, the authors stuck to their original hypotheses (that were not confirmed), they were able to discuss in a very relevant way their results and to propose some interpretations, at least partially based on the time scales involved by the productivity and diet models. Beyond all the merits of this article, I think that two issues remain largely open in relation with the dynamics of the studied systems, and would deserve future research efforts. First, on the ‘‘short’’ term (up to several decades), can we predict how the communities of plants, soil microbes, and herbivores interact to drive the dynamics of the ecosystems? Second, at the evolutionary time scale, can we understand and predict the interactions between the evolution of plant, microbe and herbivore strategies and the consequences for the functioning of the grasslands? The two issues are difficult because of the multiple feedbacks involved. One way to go further would be to complement the empirical approach with models along existing research avenues [5, 6]. References [1] Ibanez S, Foulquier A, Brun C, Colace M-P, Piton G, Bernard L, Gallet C, Clément J-C (2022) The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore diet. bioRxiv, 2022.07.04.497718, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.04.497718 [2] Hooper, D. U., Bignell, D. E., Brown, V. K., Brussaard, L., Dangerfield, J. M., Wall, D. H., Wardle, D. A., Coleman, D. C., Giller, K. E., Lavelle, P., Van der Putten, W. H., De Ruiter, P. C., et al. 2000. Interactions between aboveground and belowground biodiversity in terretrial ecosystems: patterns, mechanisms, and feedbacks. BioScience, 50, 1049-1061. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[1049:IBAABB]2.0.CO;2 [3] Barot, S., Blouin, M., Fontaine, S., Jouquet, P., Lata, J.-C., and Mathieu, J. 2007. A tale of four stories: soil ecology, theory, evolution and the publication system. PLoS ONE, 2, e1248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001248 [4] Bardgett, R. D., and Wardle, D. A. 2003. Herbivore-mediated linkages between aboveground and belowground communities. Ecology, 84, 2258-2268. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-0274 [5] Barot, S., Bornhofen, S., Loeuille, N., Perveen, N., Shahzad, T., and Fontaine, S. 2014. Nutrient enrichment and local competition influence the evolution of plant mineralization strategy, a modelling approach. J. Ecol., 102, 357-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12200 [6] Schweitzer, J. A., Juric, I., van de Voorde, T. F. J., Clay, K., van der Putten, W. H., Bailey, J. K., and Fox, C. 2014. Are there evolutionary consequences of plant-soil feedbacks along soil gradients? Func. Ecol., 28, 55-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12201

| The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore diet | Sébastien Ibanez, Arnaud Foulquier, Charles Brun, Marie-Pascale Colace, Gabin Piton, Lionel Bernard, Christiane Gallet, Jean-Christophe Clément | <p style="text-align: justify;">Herbivory can have contrasted impacts on soil microbes and nutrient cycling, which has stimulated the development of conceptual frameworks exploring the links between below- and aboveground processes. The "productiv... | Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory, Soil ecology, Terrestrial ecology | Sébastien Barot | 2022-07-14 09:06:13 | View | ||

19 Feb 2020

Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical treeSébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret https://doi.org/10.1101/351197Growth trajectories, better than organ-level functional traits, reveal intraspecific response to environmental variationRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz

Functional traits are “morpho-physio-phenological traits which impact fitness indirectly via their effects on growth, reproduction and survival” [1]. Most functional traits are defined at organ level, e.g. for leaves, roots and stems, and reflect key aspects of resource acquisition and resource use by organisms for their development and reproduction [2]. More rarely, some functional traits can be related to spatial development, such as vegetative height and lateral spread in plants. References [1] Violle, C., Navas, M. L., Vile, D., Kazakou, E., Fortunel, C., Hummel, I., & Garnier, E. (2007). Let the concept of trait be functional!. Oikos, 116(5), 882-892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x | Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical tree | Sébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret | <p style="text-align: justify;">1- Trait-environment relationships have been described at the community level across tree species. However, whether interspecific trait-environment relationships are consistent at the intraspecific level is yet unkn... |  | Botany, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Habitat selection, Ontogeny, Tropical ecology | François Munoz | 2018-06-21 17:13:17 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle