Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▼ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Mar 2023

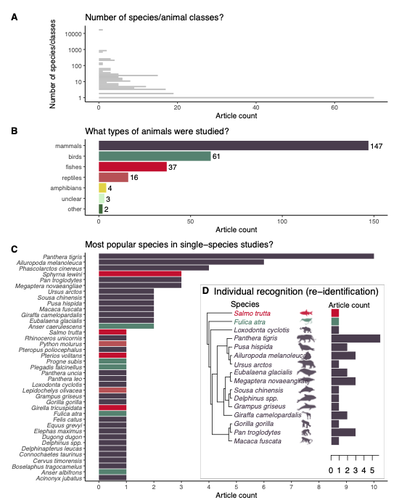

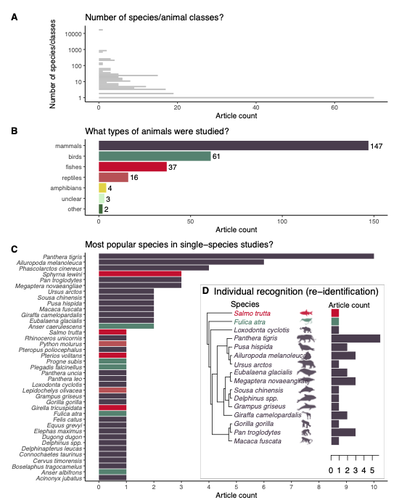

Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imageryShinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59DReview of machine learning uses for the analysis of images on wildlifeRecommended by Olivier Gimenez based on reviews by Falk Huettmann and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the field of ecology, there is a growing interest in machine (including deep) learning for processing and automatizing repetitive analyses on large amounts of images collected from camera traps, drones and smartphones, among others. These analyses include species or individual recognition and classification, counting or tracking individuals, detecting and classifying behavior. By saving countless times of manual work and tapping into massive amounts of data that keep accumulating with technological advances, machine learning is becoming an essential tool for ecologists. We refer to recent papers for more details on machine learning for ecology and evolution (Besson et al. 2022, Borowiec et al. 2022, Christin et al. 2019, Goodwin et al. 2022, Lamba et al. 2019, Nazir & Kaleem 2021, Perry et al. 2022, Picher & Hartig 2023, Tuia et al. 2022, Wäldchen & Mäder 2018). In their paper, Nakagawa et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of the literature on machine learning for wildlife imagery. Interestingly, the authors used a method unfamiliar to ecologists but well-established in medicine called rapid review, which has the advantage of being quickly completed compared to a fully comprehensive systematic review while being representative (Lagisz et al., 2022). Through a rigorous examination of more than 200 articles, the authors identified trends and gaps, and provided suggestions for future work. Listing all their findings would be counterproductive (you’d better read the paper), and I will focus on a few results that I have found striking, fully assuming a biased reading of the paper. First, Nakagawa et al. (2023) found that most articles used neural networks to analyze images, in general through collaboration with computer scientists. A challenge here is probably to think of teaching computer vision to the generations of ecologists to come (Cole et al. 2023). Second, the images were dominantly collected from camera traps, with an increase in the use of aerial images from drones/aircrafts that raise specific challenges. Third, the species concerned were mostly mammals and birds, suggesting that future applications should aim to mitigate this taxonomic bias, by including, e.g., invertebrate species. Fourth, most papers were written by authors affiliated with three countries (Australia, China, and the USA) while India and African countries provided lots of images, likely an example of scientific colonialism which should be tackled by e.g., capacity building and the involvement of local collaborators. Last, few studies shared their code and data, which obviously impedes reproducibility. Hopefully, with the journals’ policy of mandatory sharing of codes and data, this trend will be reversed. REFERENCES Besson M, Alison J, Bjerge K, Gorochowski TE, Høye TT, Jucker T, Mann HMR, Clements CF (2022) Towards the fully automated monitoring of ecological communities. Ecology Letters, 25, 2753–2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14123 Borowiec ML, Dikow RB, Frandsen PB, McKeeken A, Valentini G, White AE (2022) Deep learning as a tool for ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1640–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13901 Christin S, Hervet É, Lecomte N (2019) Applications for deep learning in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13256 Cole E, Stathatos S, Lütjens B, Sharma T, Kay J, Parham J, Kellenberger B, Beery S (2023) Teaching Computer Vision for Ecology. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.02211 Goodwin M, Halvorsen KT, Jiao L, Knausgård KM, Martin AH, Moyano M, Oomen RA, Rasmussen JH, Sørdalen TK, Thorbjørnsen SH (2022) Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: overview, applications, and outlook†. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255 Lagisz M, Vasilakopoulou K, Bridge C, Santamouris M, Nakagawa S (2022) Rapid systematic reviews for synthesizing research on built environment. Environmental Development, 43, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100730 Lamba A, Cassey P, Segaran RR, Koh LP (2019) Deep learning for environmental conservation. Current Biology, 29, R977–R982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.016 Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Francis R, Tam J, Li X, Elphinstone A, Jordan N, O’Brien J, Pitcher B, Sluys MV, Sowmya A, Kingsford R (2023) Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59D Nazir S, Kaleem M (2021) Advances in image acquisition and processing technologies transforming animal ecological studies. Ecological Informatics, 61, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101212 Perry GLW, Seidl R, Bellvé AM, Rammer W (2022) An Outlook for Deep Learning in Ecosystem Science. Ecosystems, 25, 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y Pichler M, Hartig F Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14061 Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, Risse B, Mathis A, Mathis MW, van Langevelde F, Burghardt T, Kays R, Klinck H, Wikelski M, Couzin ID, van Horn G, Crofoot MC, Stewart CV, Berger-Wolf T (2022) Perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. Nature Communications, 13, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27980-y Wäldchen J, Mäder P (2018) Machine learning for image-based species identification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13075 | Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery | Shinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford | <p>1. Machine (especially deep) learning algorithms are changing the way wildlife imagery is processed. They dramatically speed up the time to detect, count, classify animals and their behaviours. Yet, we currently have a very few systematic liter... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology | Olivier Gimenez | Anonymous | 2022-10-31 22:05:46 | View |

29 Aug 2023

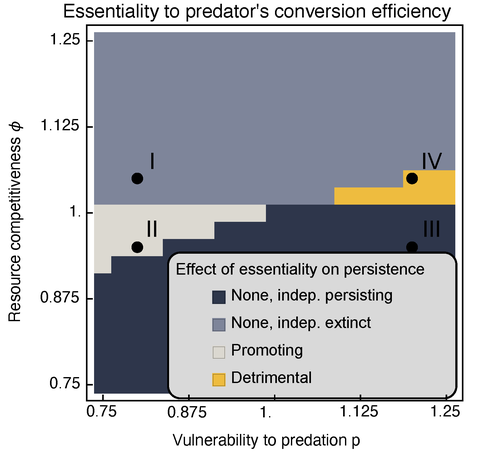

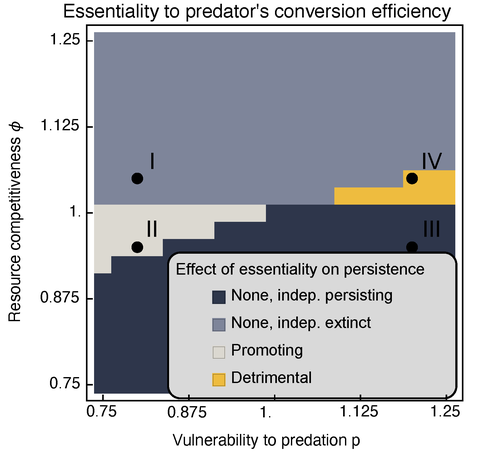

Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food websMichael Raatz https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839High-order interactions in food webs may strongly impact persistence of speciesRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer

Michael Raatz (2023) provides here a relevant exploration of higher-order interactions, i.e. interactions involving more than two related species (Terry et al. 2019), in the case of food web and competition interactions. More precisely, he shows by modeling that essential resources may significantly mediate focal species' persistence. Simultaneously, the provision of essential resources may strongly affect the resulting community structure, by driving to extinction first the predator and then, depending on the higher-order interaction, potentially also the associated competitor. Today, all ecologists should be aware of the potential effects of high-order interactions on species' (and likely on ecosystem's) fate (Golubski et al. 2016, Grilli et al. 2017). Yet, we should soon be prepared to include any high-order interaction into any interaction network (i.e. not only between species, but also between species and abiotic components, and between biotic, anthropogenic and abiotic components too). For this purpose, we will need innovative approaches such as hypergraphs (Golubski et al. 2016) and discrete-event models (Gaucherel and Pommereau 2019, Thomas et al. 2022) able to manage highly complex interactions, with numerous interacting components and variables. Such a rigorous study is a necessary and preliminary step in taking into account such a higher complexity. References Gaucherel, C. and F. Pommereau. 2019. Using discrete systems to exhaustively characterize the dynamics of an integrated ecosystem. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 00:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13242 Golubski, A. J., E. E. Westlund, J. Vandermeer, and M. Pascual. 2016. Ecological Networks over the Edge: Hypergraph Trait-Mediated Indirect Interaction (TMII) Structure trends in Ecology & Evolution 31:344-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.006 Grilli, J., G. Barabas, M. J. Michalska-Smith, and S. Allesina. 2017. Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature 548:210-213. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23273 Raatz, M. 2023. Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839 Terry, J. C. D., R. J. Morris, and M. B. Bonsall. 2019. Interaction modifications lead to greater robustness than pairwise non-trophic effects in food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 88:1732-1742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13057 Thomas, C., M. Cosme, C. Gaucherel, and F. Pommereau. 2022. Model-checking ecological state-transition graphs. PLoS Computational Biology 18:e1009657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009657 | Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs | Michael Raatz | <p style="text-align: justify;">Pairwise interactions in food webs, including those between predator and prey are often modulated by a third species. Such higher-order interactions are important structural components of natural food webs that can ... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Competition, Ecological stoichiometry, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | 2023-02-23 17:48:26 | View | |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

25 Nov 2022

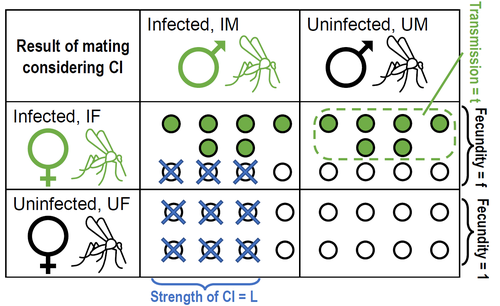

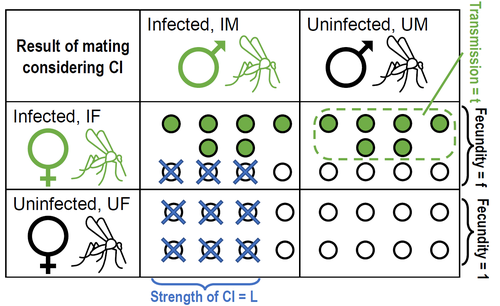

Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populationsPetteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824Population dynamics of Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeRecommended by Jorge Peña based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers"Good and evil are so close as to be chained together in the soul" Maternally inherited symbionts—microorganisms that pass from a female host to her progeny—have two main ways of increasing their own fitness. First, they can increase the fecundity or viability of infected females. This “positive fitness effects” strategy is the one commonly used by mutualistic symbionts, such as Buchnera aphidicola—the bacterial endosymbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum [4]. Second, maternally inherited symbionts can manipulate the reproduction of infected females in a way that enhances symbiont transmission at the expense of host fitness. A famous example of this “reproductive parasitism” strategy is the cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) [3] induced by bacteria of the genus Wolbachia in their arthropod and nematode hosts. CI works as a toxin-antidote system, whereby the sperm of infected males is modified in a lethal way (toxin) that can only be reverted if the egg is also infected (antidote) [1]. As a result, CI imposes a kind of conditional sterility on their hosts: while infected females are compatible with both infected and uninfected males, uninfected females experience high offspring mortality if (and only if) they mate with infected males [7]. These two symbiont strategies (positive fitness effects versus reproductive parasitism) have been traditionally studied separately, both empirically and theoretically. However, it has become clear that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive, and that a reproductive parasite can simultaneously act as a mutualist—an infection type that has been dubbed “Jekyll and Hyde” [6], after the famous novella by Robert Louis Stevenson about kind scientist Dr. Jekyll and his evil alter ego, Mr. Hyde. In important previous work, Zug and Hammerstein [7] analyzed the consequences of positive fitness effects on the dynamics of different kind of infections, including “Jekyll and Hyde” infections characterized by CI and other reproductive parasitism strategies. Building on this and related modeling framework, Karisto et al. [2] re-investigate and expand on the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism in Wolbachia infections by focusing on CI in both diplodiploid and haplodiploid populations, and by paying particular attention to the mathematical assumption structure underlying their results. Karisto et al. begin by reviewing classic models of Wolbachia infections in diplodiploid populations that assume a “negative fitness effect” (modeled as a fertility penalty on infected females), characteristic of a pure strategy of reproductive parasitism. Together with the positive frequency-dependent effects due to CI (whereby the fitness benefits to symbionts infecting females increase with the proportion of infected males in the population) this results in population dynamics characterized by two stable equilibria (the Wolbachia-free state and an interior equilibrium with a high frequency of Wolbachia-carrying hosts) separated by an unstable interior equilibrium. Wolbachia can then spread once the initial frequency is above a threshold or an invasion barrier, but is prevented from fixing by a proportion of infections failing to be passed on to offspring. Karisto et al. show that, given the assumption of negative fitness effects, the stable interior equilibrium can never feature a Wolbachia prevalence below one-half. Moreover, they convincingly argue that a prevalence greater than but close to one-half is difficult to maintain in the presence of stochastic fluctuations, as in these cases the high-prevalence stable equilibrium would be too close to the unstable equilibrium signposting the invasion barrier. Karisto et al. then relax the assumption of negative fitness effects and allow for positive fitness effects (modeled as a fertility premium on infected females) in a diplodiploid population. They show that positive fitness effects may result in situations where the original invasion threshold is now absent, the bistable coexistence dynamics are transformed into purely co-existence dynamics, and Wolbachia symbionts can now invade when rare. Karisto et al. conclude that positive fitness effects provide a plausible and potentially testable explanation for the low frequencies of symbiont-carrying hosts that are sometimes observed in nature, which are difficult to reconcile with the assumption of negative fitness effects. Finally, Karisto et al. extend their analysis to haplodiploid host populations (where all fertilized eggs develop as females). Here, they investigate two types of cytoplasmic incompatibility: a female-killing effect, similar to the CI effect studied in diplodiploid populations (the “Leptopilina type” of Vavre et al. [5]) and a masculinization effect, where CI leads to the loss of paternal chromosomes and to the development of the offspring as a male (the “Nasonia type” of Vavre et al. [5]). The models are now two-sex, which precludes a complete analytical treatment, in particular regarding the stability of fixed points. Karisto et al. compensate by conducting large numerical analyses that support their claims. Importantly, all main conclusions regarding the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism continue to hold under haplodiploidy. All in all, the analysis and results by Karisto et al. suggest that it is not necessary to resort to classical (but depending on the situation, unlikely) mechanisms, such as ongoing invasion or source-sink dynamics, to explain arthropod populations featuring low-prevalent Wolbachia infections. Instead, low-frequency equilibria might be simply due to reproductive parasites conferring beneficial fitness effects, or Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll (positive fitness effects) and Mr. Hyde (cytoplasmatic incompatibility). References [1] Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, Weill M, Sicard M, Charlat S (2019) The Toxin–Antidote Model of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Genetics and Evolutionary Implications. Trends in Genetics, 35, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2018.12.004 [2] Karisto P, Duplouy A, Vries C de, Kokko H (2022) Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations. bioRxiv, 2022.04.11.487824, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824 [3] Laven H (1956) Cytoplasmic Inheritance in Culex. Nature, 177, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/177141a0 [4] Perreau J, Zhang B, Maeda GP, Kirkpatrick M, Moran NA (2021) Strong within-host selection in a maternally inherited obligate symbiont: Buchnera and aphids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2102467118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102467118 [5] Vavre F, Fleury F, Varaldi J, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M (2000) Evidence for Female Mortality in Wolbachia-Mediated Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Haplodiploid Insects: Epidemiologic and Evolutionary Consequences. Evolution, 54, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00019.x [6] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2015) Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biological Reviews, 90, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12098 [7] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2018) Evolution of reproductive parasites with direct fitness benefits. Heredity, 120, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0022-5 | Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations | Petteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">The bacterial endosymbiont <em>Wolbachia</em> is best known for its ability to modify its host’s reproduction by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) to facilitate its own spread. Classical models predict eithe... |  | Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology | Jorge Peña | 2022-04-12 12:52:55 | View | |

21 Feb 2019

Photosynthesis of Laminaria digitata during the immersion and emersion periods of spring tidal cycles during hot, sunny weatherAline Migné, Gaspard Delebecq, Dominique Davoult, Nicolas Spilmont, Dominique Menu, Marie-Andrée Janquin and François Gévaert https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01827565v4Evaluating physiological responses of a kelp to environmental changes at its vulnerable equatorward range limitRecommended by Matthew Bracken based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding processes at species’ range limits is of paramount importance in an era of global change. For example, the boreal kelp Laminaria digitata, which dominates low intertidal and shallow subtidal rocky reefs in northwestern Europe, is declining in the equatorward portion of its range [1]. In this contribution, Migné and colleagues [2] focus on L. digitata near its southern range limit on the coast of France and use a variety of techniques to paint a complete picture of the physiological responses of the kelp to environmental changes. Importantly, and in contrast to earlier work on the species which focused on subtidal individuals (e.g. [3]), Migné et al. [2] describe responses not only in the most physiologically stressful portion of the species’ range but also in the most stressful portion of its local environment: the upper portion of its zone on the shoreline, where it is periodically exposed to aerial conditions and associated thermal and desiccation stresses. References [1] Raybaud, V., Beaugrand, G., Goberville, E., Delebecq, G., Destombe, C., Valero, M., Davoult, D., Morin, P. & Gevaert, F. (2013). Decline in kelp in west Europe and climate. PloS one, 8(6), e66044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066044 | Photosynthesis of Laminaria digitata during the immersion and emersion periods of spring tidal cycles during hot, sunny weather | Aline Migné, Gaspard Delebecq, Dominique Davoult, Nicolas Spilmont, Dominique Menu, Marie-Andrée Janquin and François Gévaert | The boreal kelp Laminaria digitata dominates the low intertidal and upper subtidal zones of moderately exposed rocky shores in north-western Europe. Due to ocean warming, this foundation species is predicted to disappear from French coasts in the ... |  | Marine ecology | Matthew Bracken | 2018-07-02 18:03:11 | View | |

21 Nov 2023

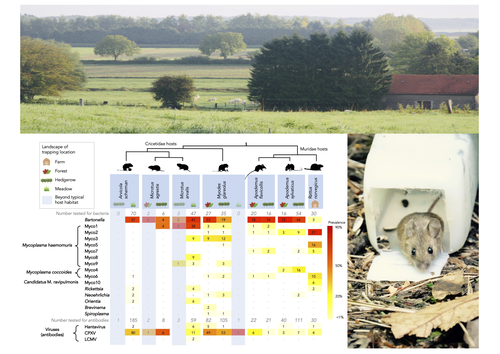

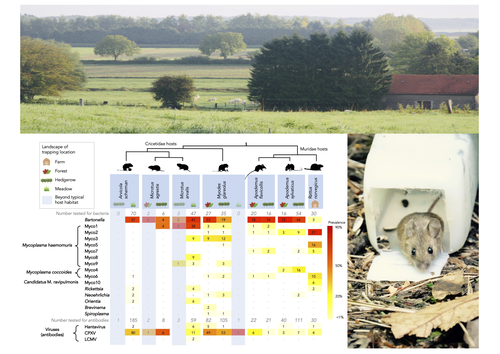

Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodentsJessica Lee Abbate, Maxime Galan, Maria Razzauti, Tarja Sironen, Liina Voutilainen, Heikki Henttonen, Patrick Gasqui, Jean-François Cosson, Nathalie Charbonnel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.09.940494Reservoirs of pestilence: what pathogen and rodent community analyses can tell us about transmission riskRecommended by Francois Massol based on reviews by Adrian Diaz, Romain Pigeault and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Adrian Diaz, Romain Pigeault and 1 anonymous reviewer

Rodents are well known as one of the main animal groups responsible for human-transmitted pathogens. As such, it seems logical to try and survey what kinds of pathogenic microbes might be harboured by wild rodents, in order to establish some baseline surveillance and prevent future zoonotic outbreaks (Bernstein et al., 2022). This is exactly what Abbate et al. (2023) endeavoured and their findings are intimidating. Based on quite a large sampling effort, they collected more than 700 rodents of seven species around two villages in northeastern France. They looked for molecular markers indicative of viral and bacterial infections and proceeded to analyze their pathogen communities using multivariate techniques. Variation in the prevalence of the different pathogens was found among host species, with e.g. signs of CPXV more prevalent in Cricetidae while some Mycoplasma strains were more prevalent in Muridae. Co-circulation of pathogens was found in all species, with some evidencing signs of up to 12 different pathogen taxa. The diversity of co-circulating pathogens was markedly different between host species and higher in adult hosts, but not affected by sex. The dataset also evinced some slight differences between habitats, with meadows harbouring a little more diversity of rodent pathogens than forests. Less intuitively, some pathogen associations seemed quite repeatable, such as the positive association of Bartonella spp. with CPXV in the montane water vole. The study allowed the authors to test several associations already described in the literature, including associations between different hemotropic Mycoplasma species. I strongly invite colleagues interested in zoonoses, emerging pandemics and more generally One Health to read the paper of Abbate et al. (2023) and try to replicate them across the world. To prevent the next sanitary crises, monitoring rodents, and more generally vertebrates, population demographics is a necessary and enlightening step (Johnson et al., 2020), but insufficient. Following the lead of colleagues working on rodent ectoparasites (Krasnov et al., 2014), we need more surveys like the one described by Abbate et al. (2023) to understand the importance of the dilution effect in the prevalence and transmission of microbial pathogens (Andreazzi et al., 2023) and the formation of epidemics. We also need other similar studies to assess the potential of different rodent species to carry pathogens more or less capable of infecting other mammalian species (Morand et al., 2015), in other places in the world. References Abbate, J. L., Galan, M., Razzauti, M., Sironen, T., Voutilainen, L., Henttonen, H., Gasqui, P., Cosson, J.-F. & Charbonnel, N. (2023) Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodents. BioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.09.940494 Andreazzi, C. S., Martinez-Vaquero, L. A., Winck, G. R., Cardoso, T. S., Teixeira, B. R., Xavier, S. C. C., Gentile, R., Jansen, A. M. & D'Andrea, P. S. (2023) Vegetation cover and biodiversity reduce parasite infection in wild hosts across ecological levels and scales. Ecography, 2023, e06579. | Pathogen community composition and co-infection patterns in a wild community of rodents | Jessica Lee Abbate, Maxime Galan, Maria Razzauti, Tarja Sironen, Liina Voutilainen, Heikki Henttonen, Patrick Gasqui, Jean-François Cosson, Nathalie Charbonnel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Rodents are major reservoirs of pathogens that can cause disease in humans and livestock. It is therefore important to know what pathogens naturally circulate in rodent populations, and to understand the factors tha... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology, Species distributions | Francois Massol | 2020-02-11 12:42:28 | View | |

13 Jul 2023

Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predatorsLoïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552Indirect effects of parasitism include increased profitability of prey to optimal foragersRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Thierry DE MEEUS and Eglantine Mathieu-BégnéEven though all living organisms are, at the same time, involved in host-parasite interactions and embedded in complex food webs, the indirect effects of parasitism are only beginning to be unveiled. Prosnier et al. investigated the direct and indirect effects of parasitism making use of a very interesting biological system comprising the freshwater zooplankton Daphnia magna and its highly specific parasite, the iridovirus DIV-1 (Daphnia-iridescent virus 1). Daphnia are typically semitransparent, but once infected develop a white phenotype with a characteristic iridescent shine due to the enlargement of white fat cells. In a combination of infection trials and comparison of white and non-white phenotypes collected in natural ponds, the authors demonstrated increased mortality and reduced lifetime fitness in infected Daphnia. Furthermore, white phenotypes had lower mobility, increased reflectance, larger body sizes and higher protein content than non-white phenotypes. As a consequence, total energy content was effectively doubled in white Daphnia when compared to non-white broodless Daphnia. Next the authors conducted foraging trials with Daphnia predators Notonecta (the backswimmer) and Phoxinus (the European minnow). Focusing on Notonecta, unchanged search time and increased handling time were more than compensated by the increased energy content of white Daphnia. White Daphnia were 24% more profitable and consistently preferred by Notonecta, as the optimal foraging theory would predict. The authors argue that menu decisions of optimal foragers in the field might be different, however, as the prevalence – and therefore availability - of white phenotypes in natural populations is very low. The study therefore contributes to our understanding of the trophic context of parasitism. One shortcoming of the study is that the authors rely exclusively on phenotypic signs for determining infection. On their side, DIV-1 is currently known to be highly specific to Daphnia, their study site is well within DIV-1 distributional range, and the symptoms of infection are very conspicuous. Furthermore, the infection trial – in which non-white Daphnia were exposed to white Daphnia homogenates - effectively caused several lethal and sublethal effects associated with DIV-1 infection, including iridescence. However, the infection trial also demonstrated that part of the exposed individuals developed intermediate traits while still keeping the non-white, non-iridescent phenotype. Thus, there may be more subtleties to the association of DIV-1 infection of Daphnia with ecological and evolutionary consequences, such as costs to resistance or covert infection, that the authors acknowledge, and that would be benefitted by coupling experimental and observational studies with the determination of actual infection and viral loads. References Prosnier L., N. Loeuille, F.D. Hulot, D. Renault, C. Piscart, B. Bicocchi, M, Deparis, M. Lam, & V. Médoc. (2023). Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552 | Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators | Loïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc | <p>Parasites are omnipresent, and their eco-evolutionary significance has aroused much interest from scientists. Parasites may affect their hosts in many ways by altering host density, vulnerability to predation, and energy content, thus modifying... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Epidemiology, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Life history, Parasitology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2022-05-20 10:15:41 | View | |

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View | |

12 May 2020

On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendationsDavid Murray-Stoker https://doi.org/10.1101/611939A stronger statistical test of stream restoration experimentsRecommended by Karl Cottenie based on reviews by Eric Harvey and Mariana Perez RochaThe metacommunity framework acknowledges that local sites are connected to other sites through dispersal, and that these connectivity patterns can influence local dynamics [1]. This framework is slowly moving from a framework that guides fundamental research to being actively applied in for instance a conservation context (e.g. [2]). Swan and Brown [3,4] analyzed the results of a suite of experimental manipulations in headwater and mainstem streams on invertebrate community structure in the context of the metacommunity concept. This was an important contribution to conservation ecology. References [1] Leibold, M. A., Holyoak, M., Mouquet, N. et al. (2004). The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi‐scale community ecology. Ecology letters, 7(7), 601-613. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x | On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendations | David Murray-Stoker | <p>Swan and Brown (2017) recently addressed the effects of restoration on stream communities under the meta-community framework. Using a combination of headwater and mainstem streams, Swan and Brown (2017) evaluated how position within a stream ne... |  | Community ecology, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Karl Cottenie | 2019-09-21 22:12:57 | View | |

18 Dec 2020

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islandsManuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamicsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter ConveyPolar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). References Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043 | Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands | Manuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault | <p>Aim Here, we aim to: (i) investigate the local effect of environmental and human-related factors on alien plant invasion in sub-Antarctic islands; (ii) explore the relationship between alien species features and their dependence on anthropogeni... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2020-07-21 21:13:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle