Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Apr 2020

Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)Frank Knight, Cristin Connor, Ramji Venkataramanan, Robert J. Asher https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.50971Is vertebral count in mammals influenced by developmental temperature? A study with Dasypus novemcinctusRecommended by Mar Sobral based on reviews by Darin Croft and ?Mammals show a very low level of variation in vertebral count, both among and within species, in comparison to other vertebrates [1]. Jordan’s rule for fishes states that the vertebral number among species increases with latitude, due to ambient temperatures during development [2]. Temperature has also been shown to influence vertebral count within species in fish [3], amphibians [4], and birds [5]. However, in mammals the count appears to be constrained, on the one hand, by a possible relationship between the development of the skeleton and the proliferations of cell lines with associated costs (neural malformations, cancer etc., [6]), and on the other by the cervical origin of the diaphragm [7]. References [1] Hautier L, Weisbecker V, Sánchez-Villagra MR, Goswami A, Asher RJ (2010) Skeletal development in sloths and the evolution of mammalian vertebral patterning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 18903–18908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010335107 | Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) | Frank Knight, Cristin Connor, Ramji Venkataramanan, Robert J. Asher | <p>The nine banded armadillo (*Dasypus novemcinctus*) is the only xenarthran mammal to have naturally expanded its range into the middle latitudes of the USA. It is not known to hibernate, but has been associated with unusually labile core body te... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Physiology, Zoology | Mar Sobral | 2019-11-22 22:57:31 | View | |

29 Dec 2018

The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food webInmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat https://doi.org/10.1101/324178From deserts to avocado orchards - understanding realized trophic interactions in communitiesRecommended by Francis John Burdon based on reviews by Owen Petchey and 2 anonymous reviewersThe late eminent ecologist Gary Polis once stated that “most catalogued food-webs are oversimplified caricatures of actual communities” and are “grossly incomplete representations of communities in terms of both diversity and trophic connections.” Not content with that damning indictment, he went further by railing that “theorists are trying to explain phenomena that do not exist” [1]. The latter critique might have been push back for Robert May´s ground-breaking but ultimately flawed research on the relationship between food-web complexity and stability [2]. Polis was a brilliant ecologist, and his thinking was clearly influenced by his experiences researching desert food webs. Those food webs possess an uncommon combination of properties, such as frequent omnivory, cannibalism, and looping; high linkage density (L/S); and a nearly complete absence of apex consumers, since few species completely lack predators or parasites [3]. During my PhD studies, I was lucky enough to visit Joshua Tree National Park on the way to a conference in New England, and I could immediately see the problems posed by desert ecosystems. At the time, I was ruminating on the “harsh-benign” hypothesis [4], which predicts that the relative importance of abiotic and biotic forces should vary with changes in local environmental conditions (from harsh to benign). Specifically, in more “harsh” environments, abiotic factors should determine community composition whilst weakening the influence of biotic interactions. However, in the harsh desert environment I saw first-hand evidence that species interactions were not diminished; if anything, they were strengthened. Teddy-bear chollas possessed murderously sharp defenses to protect precious water, creosote bushes engaged in belowground “chemical warfare” (allelopathy) to deter potential competitors, and rampant cannibalism amongst scorpions drove temporal and spatial ontogenetic niche partitioning. Life in the desert was hard, but you couldn´t expect your competition to go easy on you. References [1] Polis, G. A. (1991). Complex trophic interactions in deserts: an empirical critique of food-web theory. The American Naturalist, 138(1), 123-155. doi: 10.1086/285208 | The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web | Inmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat | <p>The mathematical theory describing small assemblages of interacting species (community modules or motifs) has proved to be essential in understanding the emergent properties of ecological communities. These models use differential equations to ... |  | Community ecology, Experimental ecology | Francis John Burdon | 2018-05-16 19:34:10 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snailKatja Leicht, Otto Seppälä https://doi.org/10.1101/449777Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snailsRecommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentisAmongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor. References [1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704 | Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail | Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä | <p>Global climate change imposes a serious threat to natural populations of many species. Estimates of the effects of climate change‐mediated environmental stresses are, however, often based only on their direct effects on organisms, and neglect t... |  | Climate change | vincent calcagno | 2018-10-22 22:19:22 | View | |

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

06 Jan 2021

Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech populationCathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio https://doi.org/10.1101/645747The complexity of predicting mortality in treesRecommended by Lucía DeSoto based on reviews by Lisa Hülsmann and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the main issues of forest ecosystems is rising tree mortality as a result of extreme weather events (Franklin et al., 1987). Eventually, tree mortality reduces forest biomass (Allen et al., 2010), although its effect on forest ecosystem fluxes seems not lasting too long (Anderegg et al., 2016). This controversy about the negative consequences of tree mortality is joined to the debate about the drivers triggering and the mechanisms accelerating tree decline. For instance, there is still room for discussion about carbon starvation or hydraulic failure determining the decay processes (Sevanto et al., 2014) or about the importance of mortality sources (Reichstein et al., 2013). Therefore, understanding and predicting tree mortality has become one of the challenges for forest ecologists in the last decade, doubling the rate of articles published on the topic (*). Although predicting the responses of ecosystems to environmental change based on the traits of species may seem a simplistic conception of ecosystem functioning (Sutherland et al., 2013), identifying those traits that are involved in the proneness of a tree to die would help to predict how forests will respond to climate threatens. (*) Number (and percentage) of articles found in Web of Sciences after searching (December the 10th, 2020) “tree mortality”: from 163 (0.006%) in 2010 to 412 (0.013%) in 2020. References Allen et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest ecology and management, 259(4), 660-684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001 | Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech population | Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio | <p>Since several studies have been reporting an increase in the decline of forests, a major issue in ecology is to better understand and predict tree mortality. The interactions between the different factors and the physiological processes giving ... |  | Climate change, Physiology, Population ecology | Lucía DeSoto | 2019-05-24 11:37:38 | View | |

15 Nov 2023

The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabirdKarine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439On the road to adulthood: exploring progressive changes in foraging behaviour during post-fledging immaturity using remote trackingRecommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Juliet Lamb and 1 anonymous reviewerIn most vertebrate species, the period of life spanning from departure from the growing site until reaching a more advanced life stage (immature or adult) is critical. During this period, juveniles are often highly vulnerable because they have not reached the morphological, physiological and behavioural maturity levels of adults yet and are therefore at high risk of mortality, e.g. through starvation, depredation or competition (e.g. Marchetti & Price 1989, Wunderle 1991, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016). In line with this, juvenile survival is most often far lower than adult survival (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992). In species with parental care, juveniles have to acquire behavioural independence from their parents and possibly establish their own territory during this period of life. Very often, this is also the period that is least well-known in the life cycle (Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016) because of reduced accessibility to individuals and/or adoption of low conspicuous behaviours. Therefore, our understanding of how juveniles acquire typical adult behaviours and how this progressively increases their survival prospects is still very limited (Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), and questions such as the length of this transition period or the cognitive (e.g. learning, memorization) mechanisms involved remain largely unresolved. This is particularly true regarding the acquisition of independent foraging behaviour (Marchetti & Price 1989). Because direct observations of juvenile behaviours are usually very difficult except in specific situations or at the cost of an enormous effort, the use of remote tracking devices can be particularly appealing in this context (e.g. Ponchon et al. 2013, Kays et al. 2015). Over the past decades, technical advances have allowed the monitoring of not only individuals’ movements at both large and small spatial scales but also their activities and behaviours based on different parameters recording e.g. speed of movement or diving depth (Whitford & Klimley 2019). Device miniaturization has in particular allowed smaller species to be equipped and/or longer periods of time to be monitored (e.g. Naef-Daenzer et al. 2005). This has opened up whole fields of research, and has been particularly used on marine seabirds. In these species, individuals are most often inaccessible when at sea, representing most of the time outside (and even within) the breeding season, and the life cycle of these long-lived species can include an extended immature period (up to many years) during which most of them will remain unseen, until they come back as breeders or pre-breeders (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992, Oro & Martínez-Abraín 2009). Survival has been found to increase gradually with age in these species before reaching high values characteristic of the adult stage. However, the mechanisms underlying this increase are still to be deciphered. The study by Delord et al. (2023) builds upon the hypothesis that juveniles gradually learn foraging techniques and movement strategies, improving their foraging efficiency, as previous data on flight parameters seemed to show in different long-lived bird species. Yet, these previous studies obtained data over a limited period of time, i.e. a few months at best. Whether these data could capture the whole dynamics of the progressive acquisition of foraging and movement skills can only be assessed by measuring behaviour over a longer time period and comparing it to similar data in adults, to account for seasonal variation in relation to both resource availability and energetic demands, e.g. due to molt. The present study (Delord et al. 2023) addresses these questions by taking advantage of longer-lasting recordings of the location and activity of juvenile, immature and adult birds obtained simultaneously to investigate changes over time in juvenile behaviour and thereby provide hints about how young progressively acquire foraging skills. This study is performed on Amsterdam albatrosses, a highly endangered long-lived sea bird, with obvious conservation issues (Thiebot et al. 2015). The results show progressive changes in foraging effort over the first two months after departure from the birth colony, but large differences remain between life stages over a much longer time frame. They also reveal strong variations between sexes and over time in the year. Overall, this study, therefore, confirms the need for very long-term data to be collected in order to address the question of progressive behavioural maturation and associated survival consequences in such species with strongly deferred maturity. Ideally, the same individuals should be monitored over different life stages, from the juvenile period up to adulthood, but this would require further technical development to release the issue of powering duration limitation. As reviewers emphasized in the first review round, one main challenge now remains to ascertain the outcome of the observed behavioural changes in foraging behaviour: we expect them to reflect improvement in foraging skills and thus performance of juveniles over time, but this would need to be tested. Collecting data on foraging efficiency is yet another challenge, that future technical developments may also help overcome. Importantly also, data were available only for individuals that could be caught again because the tracking device had to be retrieved from the bird. Here, a substantial fraction of the loggers (one-fifth) could not be found again (Delord et al. 2023). To what extent the birds for which no data could be obtained are a random sample of the equipped birds would also need to be assessed. The further development of remote tracking techniques allowing data to be downloaded from a long distance should help further exploration of behavioural ontogeny of juveniles while maturing and its survival consequences. Because the maturation process explored here is likely to show very different characteristics (e.g. timing and speed) in smaller / shorter-lived species (see Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), the development of miniaturization is also expected to allow further investigation of post-fledging behavioural maturation in a wider range of bird species. Our understanding of this crucial life phase in different types of species should thus continue to progress in the coming years. References Cox W. A., Thompson F. R. III, Cox A. S. & Faaborg J. 2014. Post-fledging survival in passerine birds and the value of post-fledging studies to conservation. Journal of Wildlife Management, 78: 183-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.670 Delord K., Weimerskirch H. & Barbraud C. 2023. The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird. bioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439 Kays R., Crofoot M. C., Jetz W. & Wikelski M. 2015. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science, 348 (6240). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2478 Marchetti K: & Price T. 1989. Differences in the foraging of juvenile and adult birds: the importance of developmental constraints. Biological Reviews, 64: 51-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1989.tb00638.x Naef-Daenzer B., Fruh D., Stalder M., Wetli P. & Weise E. 2005. Miniaturization (0.2 g) and evaluation of attachment techniques of telemetry transmitters. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 208: 4063–4068. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01870 Naef-Daenzer B. & Grüebler M. U. 2016. Post-fledging survival of altricial birds: ecological determinants and adaptation. Journal of Field Ornithology, 87: 227-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofo.12157 Oro D. & Martínez-Abraín A. 2009. Ecology and behavior of seabirds. Marine Ecology, pp.364-389. Ponchon A., Grémillet D., Doligez B., Chambert T., Tveera T., Gonzàles-Solìs J & Boulinier T. 2013. Tracking prospecting movements involved in breeding habitat selection: insights, pitfalls and perspectives. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00259.x Thiebot J.-B., Delord K., Barbraud C., Marteau C. & Weimerskirch H. 2015. 167 individuals versus millions of hooks: bycatch mitigation in longline fisheries underlies conservation of Amsterdam albatrosses. Aquatic Conservation 26: 674-688. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2578 Whitford M & Klimley A. P. An overview of behavioral, physiological, and environmental sensors used in animal biotelemetry and biologging studies. Animal Biotelemetry, 7: 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0189-z Wooller R.D., Bradley J. S. & Croxall J. P. 1992. Long-term population studies of seabirds. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 111-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(92)90143-y Wunderle J. M. 1991. Age-specific foraging proficiency in birds. Current Ornithology, 8: 273-324. | The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird | Karine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The transition to independent foraging represents an important developmental stage in the life cycle of most vertebrate animals. Juveniles differ from adults in various life history traits and tend to survive less w... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Foraging, Ontogeny | Blandine Doligez | 2021-10-26 07:51:49 | View | |

10 Aug 2023

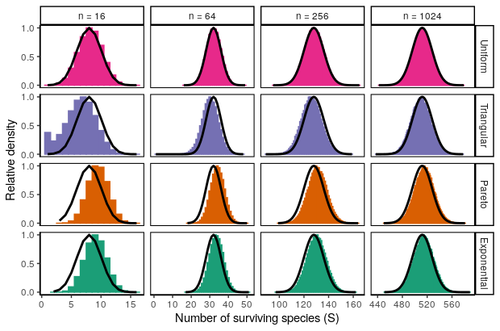

Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-offZachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867Assembly in metacommunities driven by a competition-colonization tradeoff: more species in, more species outRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Canan Karakoç and 1 anonymous reviewerThe output of a community model depends on how you set its parameters. Thus, analyses of specific parameter settings hardwire the results to specific ecological scenarios. Because more general answers are often of interest, one tradition is to give models a statistical treatment: one summarizes how model parameters vary across species, and then predicts how changing the summary, instead of the individual parameters themselves, would change model output. Arguably the best-known example is the work initiated by May, showing that the properties of a community matrix, encoding effects species have on each other near their equilibrium, determine stability (1,2). More recently, this statistical treatment has also been applied to one of community ecology’s more prickly and slippery subjects: community assembly, which deals with the question “Given some regional species pool, which species will be able to persist together at some local ecosystem?”. Summaries of how species grow and interact in this regional pool predict the fraction of survivors and their relative abundances, the kind of dynamics, and various kinds of stability (3,4). One common characteristic of such statistical treatments is the assumption of disorder: if species do not interact in too structured ways, simple and therefore powerful predictions ensue that often stand up to scrutiny in relatively ordered systems. 2. Allesina, S. & Tang, S. (2015). The stability–complexity relationship at age 40: a random matrix perspective. Population Ecology, 57, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10144-014-0471-0 3. Bunin, G. (2016). Interaction patterns and diversity in assembled ecological communities. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.04734. 5. Miller, Z. R., Clenet, M., Libera, K. D., Massol, F. & Allesina, S. (2023). Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off. bioRxiv 2023.03.23.533867, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.23.533867 6. Serván, C. A. & Allesina, S. (2021). Tractable models of ecological assembly. Ecology Letters, 24, 1029–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13702 | Coexistence of many species under a random competition-colonization trade-off | Zachary R. Miller, Maxime Clenet, Katja Della Libera, François Massol, Stefano Allesina | <p>The competition-colonization trade-off is a well-studied coexistence mechanism for metacommunities. In this setting, it is believed that coexistence of all species requires their traits to satisfy restrictive conditions limiting their similarit... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Frederik De Laender | 2023-03-30 20:42:48 | View | |

25 Oct 2021

The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakesNicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner https://doi.org/10.1101/373332The difficult interpretation of species co-distributionRecommended by Dominique Gravel based on reviews by Anthony Maire and Emilie MackeEcology is the study of the distribution of organisms in space and time and their interactions. As such, there is a tradition of studies relating abiotic environmental conditions to species distribution, while another one is concerned by the effects of consumers on the abundance of their resources. Interestingly, joining the dots appears more difficult than it would suggest: eluding the effect of species interactions on distribution remains one of the greatest challenges to elucidate nowadays (Kissling et al. 2012). Theory suggests that yes, species interactions such as predation and competition should influence range limits (Godsoe et al. 2017), but the common intuition among many biogeographers remains that over large areas such as regions and continents, environmental drivers like temperature and precipitation overwhelm their local effects. Answering this question is of primary importance in the context where species are moving around with climate warming. Inconsistencies in food web structure may arise with asynchronized movements of consumers and their resources, leading to a major disruption in regulation and potentially ecosystem functioning. Solving this problem, however, remains very challenging because we have to rely on observational data since experiments are hard to perform at the biogeographical scale. The study of St-Gelais is an interesting step forward to solve this problem. Their main objective was to assess the strength of the association between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities at a large spatial scale, looking at the spatial covariation of both taxonomic and functional composition. To do so, they undertook a massive survey of more than 100 lakes across three regions of the boreal region of Québec. Species and functional composition were recorded, along with a set of abiotic variables. Classic community ecology at this point. The difficulty they faced was to disentangle the multiple causal relationships involved in the distribution of both trophic levels. Teasing apart bottom-up and top-down forces driving the assembly of plankton communities using observational data is not an easy task. On the one hand, both trophic levels could respond to variations in temperature, nutrient availability and dissolved organic carbon. The interpretation is fairly straightforward if the two levels respond to different factors, but the situation is much more complicated when they do respond similarly. There are potentially three possible underlying scenarios. First, the phyto and zooplankton communities may share the same environmental requirements, thereby generating a joint distribution over gradients such as temperature and nutrient availability. Second, the abiotic environment could drive the distribution of the phytoplankton community, which would then propagate up and influence the distribution of the zooplankton community. Alternatively, the abiotic environment could constrain the distribution of the zooplankton, which could then affect the one of phytoplankton. In addition to all of these factors, St-Gelais et al also consider that dispersal may limit the distribution, well aware of previous studies documenting stronger dispersal limitations for zooplankton communities. Unfortunately, there is not a single statistical approach that could be taken from the shelf and used to elucidate drivers of co-distribution. Joint species distribution was once envisioned as a major step forward in this direction (Warton et al. 2015), but there are several limits preventing the direct interpretation that co-occurrence is linked to interactions (Blanchet et al. 2020). Rather, St-Gelais used a variety of multivariate statistics to reveal the structure in their observational data. First, using a Procrustes analysis (a method testing if the spatial variation of one community is correlated to the structure of another community), they found a significant correlation between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities, indicating a taxonomic coupling between the groups. Interestingly, this observation was maintained for functional composition only when interaction-related traits were considered. At this point, these results strongly suggest that interactions are involved in the correlation, but it's hard to decipher between bottom-up and top-down perspectives. A complementary analysis performed with a constrained ordination, per trophic level, provided complementary pieces of information. First observation was that only functional variation was found to be related to the different environmental variables, not taxonomic variation. Despite that trophic levels responded to water quality variables, spatial autocorrelation was more important for zooplankton communities and the two layers appear to respond to different variables. It is impossible with those results to formulate a strong conclusion about whether grazing influence the co-distribution of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities. That's the mere nature of observational data. While there is a strong spatial association between them, there are also diverging responses to the different environmental variables considered. But the contrast between taxonomic and functional composition is nonetheless informative and it seems that beyond the idiosyncrasies of species composition, trait distribution may be more informative and general. Perhaps the most original contribution of this study is the hierarchical approach to analyze the data, combined with the simultaneous analysis of taxonomic and functional distributions. Having access to a vast catalog of multivariate statistical techniques, a careful selection of analyses helps revealing key features in the data, rejecting some hypotheses and accepting others. Hopefully, we will see more and more of such multi-trophic approaches to distribution because it is now clear that the factors driving distribution are much more complicated than anticipated in more traditional analyses of community data. Biodiversity is more than a species list, it is also all of the interactions between them, influencing their distribution and abundance (Jordano 2016). References Blanchet FG, Cazelles K, Gravel D (2020) Co-occurrence is not evidence of ecological interactions. Ecology Letters, 23, 1050–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13525 Godsoe W, Jankowski J, Holt RD, Gravel D (2017) Integrating Biogeography with Contemporary Niche Theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.03.008 Jordano P (2016) Chasing Ecological Interactions. PLOS Biology, 14, e1002559. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002559 Kissling WD, Dormann CF, Groeneveld J, Hickler T, Kühn I, McInerny GJ, Montoya JM, Römermann C, Schiffers K, Schurr FM, Singer A, Svenning J-C, Zimmermann NE, O’Hara RB (2012) Towards novel approaches to modelling biotic interactions in multispecies assemblages at large spatial extents. Journal of Biogeography, 39, 2163–2178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02663.x St-Gelais NF, Vogt RJ, Giorgio PA del, Beisner BE (2021) The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes. bioRxiv, 373332, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/373332 Warton DI, Blanchet FG, O’Hara RB, Ovaskainen O, Taskinen S, Walker SC, Hui FKC (2015) So Many Variables: Joint Modeling in Community Ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30, 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.007 Wisz MS, Pottier J, Kissling WD, Pellissier L, Lenoir J, Damgaard CF, Dormann CF, Forchhammer MC, Grytnes J-A, Guisan A, Heikkinen RK, Høye TT, Kühn I, Luoto M, Maiorano L, Nilsson M-C, Normand S, Öckinger E, Schmidt NM, Termansen M, Timmermann A, Wardle DA, Aastrup P, Svenning J-C (2013) The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews, 88, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x | The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes | Nicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner | <p>Strong trophic interactions link primary producers (phytoplankton) and consumers (zooplankton) in lakes. However, the influence of such interactions on the biogeographical distribution of the taxa and functional traits of planktonic organ... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Species distributions | Dominique Gravel | 2018-07-24 15:01:51 | View | |

12 Jun 2019

Environmental heterogeneity drives tsetse fly population dynamics and controlCecilia H, Arnoux S, Picault S, Dicko A, Seck MT, Sall B, Bassene M, Vreysen M, Pagabeleguem S, Bance A, Bouyer J, Ezanno P https://doi.org/10.1101/493650Modeling jointly landscape complexity and environmental heterogeneity to envision new strategies for tsetse flies controlRecommended by Benjamin Roche based on reviews by Timothée Vergne and 1 anonymous reviewerToday, understanding spatio-temporal dynamics of pathogens is pivotal to understand their transmission and controlling them. First, understanding this dynamics can reveal the ecology of their transmission [1]. Indeed, such knowledge, based on data that are quite easy to access, can shed light on transmission modes, which could rely on different animal species that can be spatially distributed in a non-uniform way [2]. This is especially true for pathogens with complex life-cycles, despite that investigating such dynamics is very challenging and rely mostly on mathematical models. References [1] Grenfell, B. T., Bjørnstad, O. N., & Kappey, J. (2001). Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature, 414(6865), 716-723. doi: 10.1038/414716a | Environmental heterogeneity drives tsetse fly population dynamics and control | Cecilia H, Arnoux S, Picault S, Dicko A, Seck MT, Sall B, Bassene M, Vreysen M, Pagabeleguem S, Bance A, Bouyer J, Ezanno P | <p>A spatially and temporally heterogeneous environment may lead to unexpected population dynamics. Knowledge still is needed on which of the local environment properties favour population maintenance at larger scale. For pathogen vectors, such as... |  | Biological control, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Benjamin Roche | 2018-12-14 12:13:39 | View | |

23 Mar 2020

Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascadesArnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne https://doi.org/10.1101/722140Tell me what you’ve eaten, I’ll tell you how much you’ll eat (and be eaten)Recommended by Sara Magalhães and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 1 anonymous reviewerTritrophic interactions have a central role in ecological theory and applications [1-3]. Particularly, systems comprised of plants, herbivores and predators have historically received wide attention given their ubiquity and economic importance [4]. Although ecologists have long aimed to understand the forces that govern alternating ecological effects at successive trophic levels [5], several key open questions remain (at least partially) unanswered [6]. In particular, the analysis of complex food webs has questioned whether ecosystems can be viewed as a series of trophic chains [7,8]. Moreover, whether systems are mostly controlled by top-down (trophic cascades) or bottom-up processes remains an open question [6]. References [1] Price, P. W., Bouton, C. E., Gross, P., McPheron, B. A., Thompson, J. N., & Weis, A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 11(1), 41-65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353 | Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades | Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne | <p>Trophic cascades, the indirect effect of predators on non-adjacent lower trophic levels, are important drivers of the structure and dynamics of ecological communities. However, the influence of intraspecific trait variation on the strength of t... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Food webs, Population ecology | Sara Magalhães | 2019-08-02 09:11:03 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle