Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Apr 2024

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

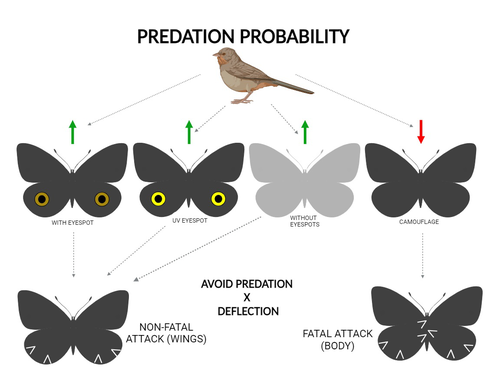

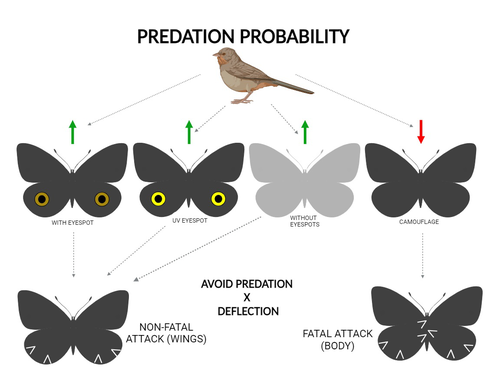

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

12 Sep 2023

Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patternsYuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913The impact of process at different scales on diversity and ecosystem functioning: a huge challengeRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer

Scale is a big topic in ecology [1]. Environmental variation happens at particular scales. The typical scale at which organisms disperse is species-specific, but, as a first approximation, an ensemble of similar species, for instance, trees, could be considered to share a typical dispersal scale. Finally, characteristic spatial scales of species interactions are, in general, different from the typical scales of dispersal and environmental variation. Therefore, conceptually, we can distinguish these three characteristic spatial scales associated with three different processes: species selection for a given environment (E), dispersal (D), and species interactions (I), respectively. From the famous species-area relation to the spatial distribution of biomass and species richness, the different macro-ecological patterns we usually study emerge from an interplay between dispersal and local interactions in a physical environment that constrains species establishment and persistence in every location. To make things even more complicated, local environments are often modified by the species that thrive in them, which establishes feedback loops. It is usually assumed that local interactions are short-range in comparison with species dispersal, and dispersal scales are typically smaller than the scales at which the environment varies (I < D < E, see [2]), but this should not always be the case. The authors of this paper [2] relax this typical assumption and develop a theoretical framework to study how diversity and ecosystem functioning are affected by different relations between the typical scales governing interactions, dispersal, and environmental variation. This is a huge challenge. First, diversity and ecosystem functioning across space and time have been empirically characterized through a wide variety of macro-ecological patterns. Second, accommodating local interactions, dispersal and environmental variation and species environmental preferences to model spatiotemporal dynamics of full ecological communities can be done also in a lot of different ways. One can ask if the particular approach suggested by the authors is the best choice in the sense of producing robust results, this is, results that would be predicted by alternative modeling approaches and mathematical analyses [3]. The recommendation here is to read through and judge by yourself. The main unusual assumption underlying the model suggested by the authors is non-local species interactions. They introduce interaction kernels to weigh the strength of the ecological interaction with distance, which gives rise to a system of coupled integro-differential equations. This kernel is the key component that allows for control and varies the scale of ecological interactions. Although this is not new in ecology [4], and certainly has a long tradition in physics ---think about the electric or the gravity field, this approach has been widely overlooked in the development of the set of theoretical frameworks we have been using over and over again in community ecology, such as the Lotka-Volterra equations or, more recently, the metacommunity concept [5]. In Physics, classic fields have been revised to account for the fact that information cannot travel faster than light. In an analogous way, a focal individual cannot feel the presence of distant neighbors instantaneously. Therefore, non-local interactions do not exist in ecological communities. As the authors of this paper point out, they emerge in an effective way as a result of non-random movements, for instance, when individuals go regularly back and forth between environments (see [6], for an application to infectious diseases), or even migrate between regions. And, on top of this type of movement, species also tend to disperse and colonize close (or far) environments. Individual mobility and dispersal are then two types of movements, characterized by different spatial-temporal scales in general. Species dispersal, on the one hand, and individual directed movements underlying species interactions, on the other, are themselves diverse across species, but it is clear that they exist and belong to two distinct categories. In spite of the long and rich exchange between the authors' team and the reviewers, it was not finally clear (at least, to me and to one of the reviewers) whether the model for the spatio-temporal dynamics of the ecological community (see Eq (1) in [2]) is only presented as a coupled system of integro-differential equations on a continuous landscape for pedagogical reasons, but then modeled on a discrete regular grid for computational convenience. In the latter case, the system represents a regular network of local communities, becomes a system of coupled ODEs, and can be numerically integrated through the use of standard algorithms. By contrast, in the former case, the system is meant to truly represent a community that develops on continuous time and space, as in reaction-diffusion systems. In that case, one should keep in mind that numerical instabilities can arise as an artifact when integrating both local and non-local spatio-temporal systems. Spatial patterns could be then transient or simply result from these instabilities. Therefore, when analyzing spatiotemporal integro-differential equations, special attention should be paid to the use of the right numerical algorithms. The authors share all their code at https://zenodo.org/record/5543191, and all this can be checked out. In any case, the whole discussion between the authors and the reviewers has inherent value in itself, because it touches on several limitations and/or strengths of the author's approach, and I highly recommend checking it out and reading it through. Beyond these methodological issues, extensive model explorations for the different parameter combinations are presented. Several results are reported, but, in practice, what is then the main conclusion we could highlight here among all of them? The authors suggest that "it will be difficult to manage landscapes to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functioning simultaneously, despite their causative relationship", because, first, "increasing dispersal and interaction scales had opposing References [1] Levin, S. A. 1992. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941447 [2] Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain. 2023. Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913 [3] Baron, J. W. and Galla, T. 2020. Dispersal-induced instability in complex ecosystems. Nature Communications 11, 6032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19824-4 [4] Cushing, J. M. 1977. Integrodifferential equations and delay models in population dynamics [5] M. A. Leibold, M. Holyoak, N. Mouquet, P. Amarasekare, J. M. Chase, M. F. Hoopes, R. D. Holt, J. B. Shurin, R. Law, D. Tilman, M. Loreau, A. Gonzalez. 2004. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters, 7(7): 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x [6] M. Pardo-Araujo, D. García-García, D. Alonso, and F. Bartumeus. 2023. Epidemic thresholds and human mobility. Scientific reports 13 (1), 11409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38395-0 | Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns | Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain | <p style="text-align: justify;">Ecology is a science of scale, which guides our description of both ecological processes and patterns, but we lack a systematic understanding of how process scale and pattern scale are connected. Recent calls for a ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Ecosystem functioning, Landscape ecology, Theoretical ecology | David Alonso | 2021-10-13 23:24:45 | View | ||

19 Aug 2020

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metricsF. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux https://doi.org/10.1101/640995Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systemsRecommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersConservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4]. References [1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton. | Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View | |

12 May 2022

Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapesYasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fujaco, Mariangela Garcia Praca Leite, Joice Paiva Vidigal Martins, Graziella Franca Monteiro, Rodolfo Dirzo https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375Complex but positive diversity - ecosystem functioning relationships in Riparian tropical forestsRecommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many ecological drivers can impact ecosystem functionality and multifunctionality, with the latter describing the joint impact of different functions on ecosystem performance and services. It is now generally accepted that taxonomically richer ecosystems are better able to sustain high aggregate functionality measures, like energy transfer, productivity or carbon storage (Buzhdygan 2020, Naeem et al. 2009), and different ecosystem services (Marselle et al. 2021) than those that are less rich. Antonini et al. (2022) analysed an impressive dataset on animal and plant richness of tropical riparian forests and abundances, together with data on key soil parameters. Their work highlights the importance of biodiversity on functioning, while accounting for a manifold of potentially covarying drivers. Although the key result might not come as a surprise, it is a useful contribution to the diversity - ecosystem functioning topic, because it is underpinned with data from tropical habitats. To date, most analyses have focused on temperate habitats, using data often obtained from controlled experiments. The paper also highlights that diversity–functioning relationships are complicated. Drivers of functionality vary from site to site and each measure of functioning, including parameters as demonstrated here, can be influenced by very different sets of predictors, often associated with taxonomic and trait diversity. Single correlative comparisons of certain aspects of diversity and functionality might therefore return very different results. Antonini et al. (2022) show that, in general, using 22 predictors of functional diversity, varying predictor subsets were positively associated with soil functioning. Correlational analyses alone cannot resolve the question of causal link. Future studies should therefore focus on inferring precise mechanisms behind the observed relationships, and the environmental constraints on predictor subset composition and strength. References Antonini Y, Beirão MV, Costa FV, Azevedo CS, Wojakowski MM, Kozovits AR, Pires MRS, Sousa HC de, Messias MCTB, Fujaco MA, Leite MGP, Vidigal JP, Monteiro GF, Dirzo R (2022) Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes. bioRxiv, 2021.09.08.459375, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.459375 Buzhdygan OY, Meyer ST, Weisser WW, Eisenhauer N, Ebeling A, Borrett SR, Buchmann N, Cortois R, De Deyn GB, de Kroon H, Gleixner G, Hertzog LR, Hines J, Lange M, Mommer L, Ravenek J, Scherber C, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Scheu S, Schmid B, Steinauer K, Strecker T, Tietjen B, Vogel A, Weigelt A, Petermann JS (2020) Biodiversity increases multitrophic energy use efficiency, flow and storage in grasslands. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1123-8 Marselle MR, Hartig T, Cox DTC, de Bell S, Knapp S, Lindley S, Triguero-Mas M, Böhning-Gaese K, Braubach M, Cook PA, de Vries S, Heintz-Buschart A, Hofmann M, Irvine KN, Kabisch N, Kolek F, Kraemer R, Markevych I, Martens D, Müller R, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Potts JM, Stadler J, Walton S, Warber SL, Bonn A (2021) Pathways linking biodiversity to human health: A conceptual framework. Environment International, 150, 106420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106420 Naeem S, Bunker DE, Hector A, Loreau M, Perrings C (Eds.) (2009) Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning, and Human Wellbeing: An Ecological and Economic Perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199547951.001.0001 | Riparian forest restoration as sources of biodiversity and ecosystem functions in anthropogenic landscapes | Yasmine Antonini, Marina Vale Beirao, Fernanda Vieira Costa, Cristiano Schetini Azevedo, Maria Wojakowski, Alessandra Kozovits, Maria Rita Silverio Pires, Hildeberto Caldas Sousa, Maria Cristina Teixeira Braga Messias, Maria Augusta Goncalves Fuja... | <ol> <li style="text-align: justify;">Restoration of tropical riparian forests is challenging, since these ecosystems are the most diverse, dynamic, and complex physical and biological terrestrial habitats. This study tested whether biodiversity ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecological successions, Ecosystem functioning, Terrestrial ecology | Werner Ulrich | 2021-09-10 10:51:23 | View | |

06 Mar 2020

Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food websPierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault https://doi.org/10.1101/276592New insights into the role of nutrient cycling in food web dynamicsRecommended by Samraat Pawar based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the factors that govern the relationship between structure, stability and functioning of food webs has been a central problem in ecology for many decades. Historically, apart from microbial and soil food webs, the role of nutrient cycling has largely been ignored in theoretical and empirical food web studies. A prime example of this is the widespread use of Lotka-Volterra type models in theoretical studies; these models per se are not designed to capture the effect of nutrients being released back into the system by interacting populations. Thus overall, we still lack a general understanding of how nutrient cycling affects food web dynamics. References [1] Quévreux, P., Barot, S. and E. Thébault (2020) Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs. bioRxiv, 276592, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/276592 | Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs | Pierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault | <p>Nutrient cycling is fundamental to ecosystem functioning. Despite recent major advances in the understanding of complex food web dynamics, food web models have so far generally ignored nutrient cycling. However, nutrient cycling is expected to ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Samraat Pawar | 2018-11-03 21:47:37 | View | ||

30 May 2024

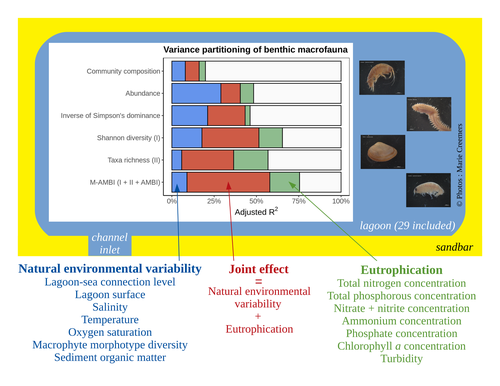

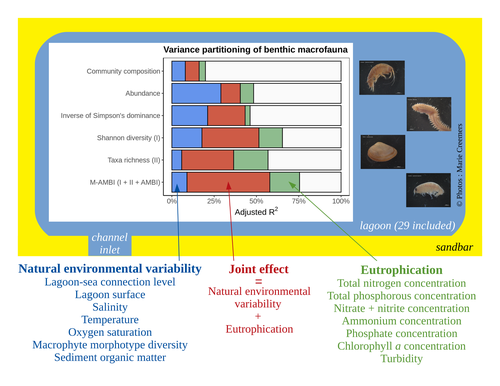

Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoonsAuriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.18.504439Untangling Eutrophication Effects on Coastal Lagoon EcosystemsRecommended by Nathalie Niquil based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright

Disentangling the effects on ecosystem structure and functioning of natural and human-induced impacts in transitional waters is a great challenge in coast ecology. This is due to the observation that the ecosystems of transitional waters are naturally dynamic systems with characteristics of stressed systems. For example, the benthic communities present low species richness and high abundance of species with a high tolerance to variations, e.g., salinity. This general observation is known as the paradigm of the “Transitional Waters Quality Paradox” (Zaldívar et al., 2008) derived from the previously described “Estuarine Quality Paradox” (Elliott and Quintino, 2007). In Jones et al. (2024) “Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons”, a great diversity of lagoons is analyzed to disentangle the effects of eutrophication from those of natural environmental variability on benthic macroinvertebrates and understanding the links between environmental variables affecting benthic macroinvertebrates. These authors use a very elegant set of numerical approaches, including correlograms, linear models and variance partitioning. They apply this suite to a dataset of macrobenthic invertebrate abundances and environmental variables from 29 Mediterranean coastal lagoons in France. Through this suite of analyses, they demonstrate the strong complexity of the mechanisms interplaying in a situation of eutrophication on lagoon macrobenthos. The mechanisms involved are direct, like toxicity, or indirect, for example, through modifications of the sediment's biogeochemistry. Such a result on the different interactions involved is very important in the context of the search for indicators to define ecosystem status. Improving the definition of metrics is essential in environmental management decisions. References Elliott, M. and Quintino, V. (2007) The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.02.003 Zaldívar, J. (2008). Eutrophication in transitional waters: an overview. https://doi.org/10.1285/I18252273V2N1P1 | Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons | Auriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are transitional ecosystems that host a unique diversity of species and support many ecosystem services. Owing to their position at the interface between land and sea, they are also subject to increa... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Marine ecology | Nathalie Niquil | Matthew J. Pruden | 2023-09-08 11:26:01 | View |

01 Mar 2023

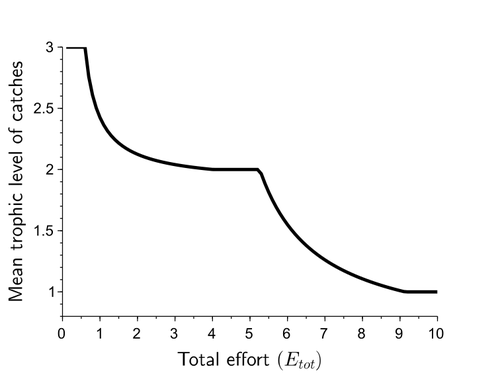

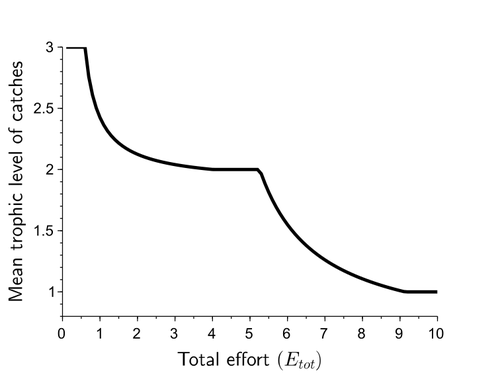

Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systemsEric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/290460Adaptive harvesting, “fishing down the food web”, and regime shiftsRecommended by Amanda Lynn Caskenette based on reviews by Pierre-Yves HERNVANN and 1 anonymous reviewerThe mean trophic level of catches in world fisheries has generally declined over the 20th century, a phenomenon called "fishing down the food web" (Pauly et al. 1998). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this decline including the collapse of, or decline in, higher trophic level stocks leading to the inclusion of lower trophic level stocks in the fishery. Fishing down the food web may lead to a reduction in the resilience, i.e., the capacity to rebound from change, of the fished community, which is concerning given the necessity of resilience in the face of climate change. The practice of adaptive harvesting, which involves fishing stocks based on their availability, can also result in a reduction in the average trophic level of a fishery (Branch et al. 2010). Adaptive harvesting, similar to adaptive foraging, can affect the resilience of fisheries. Generally, adaptive foraging acts as a stabilizing force in communities (Valdovinos et al. 2010), however it is not clear how including harvesters as the adaptive foragers will affect the resilience of the system. Tromeur and Loeuille (2023) analyze the effects of adaptively harvesting a trophic community. Using a system of ordinary differential equations representing a predator-prey model where both species are harvested, the researchers mathematically analyze the impact of increasing fishing effort and adaptive harvesting on the mean trophic level and resilience of the fished community. This is achieved by computing the equilibrium densities and equilibrium allocation of harvest effort. In addition, the researchers numerically evaluate adaptive harvesting in a tri-trophic system (predator, prey, and resource). The study focuses on the effect of adaptively distributing harvest across trophic levels on the mean trophic level of catches, the propensity for regime shifts to occur, the ability to return to equilibrium after a disturbance, and the speed of this return. The results indicate that adaptive harvesting leads to a decline in the mean trophic level of catches, resulting in “fishing down the food web”. Furthermore, the study shows that adaptive harvesting may harm the overall resilience of the system. Similar results were observed numerically in a tri-trophic community. While adaptive foraging is generally a stabilizing force on communities, the researchers found that adaptive harvesting can destabilize the harvested community. One of the key differences between adaptive foraging models and the model presented here, is that the harvesters do not exhibit population dynamics. This lack of a numerical response by the harvesters to decreasing population sizes of their stocks leads to regime shifts. The realism of a fishery that does not respond numerically to declining stock is debatable, however it is very likely that there will a least be significant delays due to social and economic barriers to leaving the fishery, that will lead to similar results. This study is not unique in demonstrating the ability of adaptive harvesting to result in “fishing down the food web”. As pointed out by the researchers, the same results have been shown with several different model formulations (e.g., age and size structured models). Similarly, this study is not unique to showing that increasing adaptation speeds decreases the resilience of non-linear predator-prey systems by inducing oscillatory behaviours. Much of this can be explained by the destabilising effect of increasing interaction strengths on food webs (McCann et al. 1998). By employing a straightforward model, the researchers were able to demonstrate that adaptive harvesting, a common strategy employed by fishermen, can result in a decline in the average trophic level of catches, regime shifts, and reduced resilience in the fished community. While previous studies have observed some of these effects, the fact that the current study was able to capture them all with a simple model is notable. This modeling approach can offer insight into the role of human behavior on the complex dynamics observed in fisheries worldwide. References Branch, T. A., R. Watson, E. A. Fulton, S. Jennings, C. R. McGilliard, G. T. Pablico, D. Ricard, et al. 2010. The trophic fingerprint of marine fisheries. Nature 468:431–435. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09528 Tromeur, E., and N. Loeuille. 2023. Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems. bioRxiv 290460, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/290460 McCann, K., A. Hastings, and G.R. Huxel. 1998. Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature 395: 794-798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427 Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Froese, and F. Torres Jr. 1998. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–86. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860 Valdovinos, F.S., R. Ramos-Jiliberto, L. Garay-Naravez, P. Urbani, and J.A. Dunne. 2010. Consequences of adaptive behaviour for the structure and dynamics of food webs. Ecology Letters 13: 1546-1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01535.x | Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems | Eric Tromeur, Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Many world fisheries display a declining mean trophic level of catches. This "fishing down the food web" is often attributed to reduced densities of high-trophic-level species. We show here that the fishing down pattern can actually emerge from... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Population ecology, Theoretical ecology | Amanda Lynn Caskenette | 2022-05-03 21:09:35 | View | |

05 Feb 2020

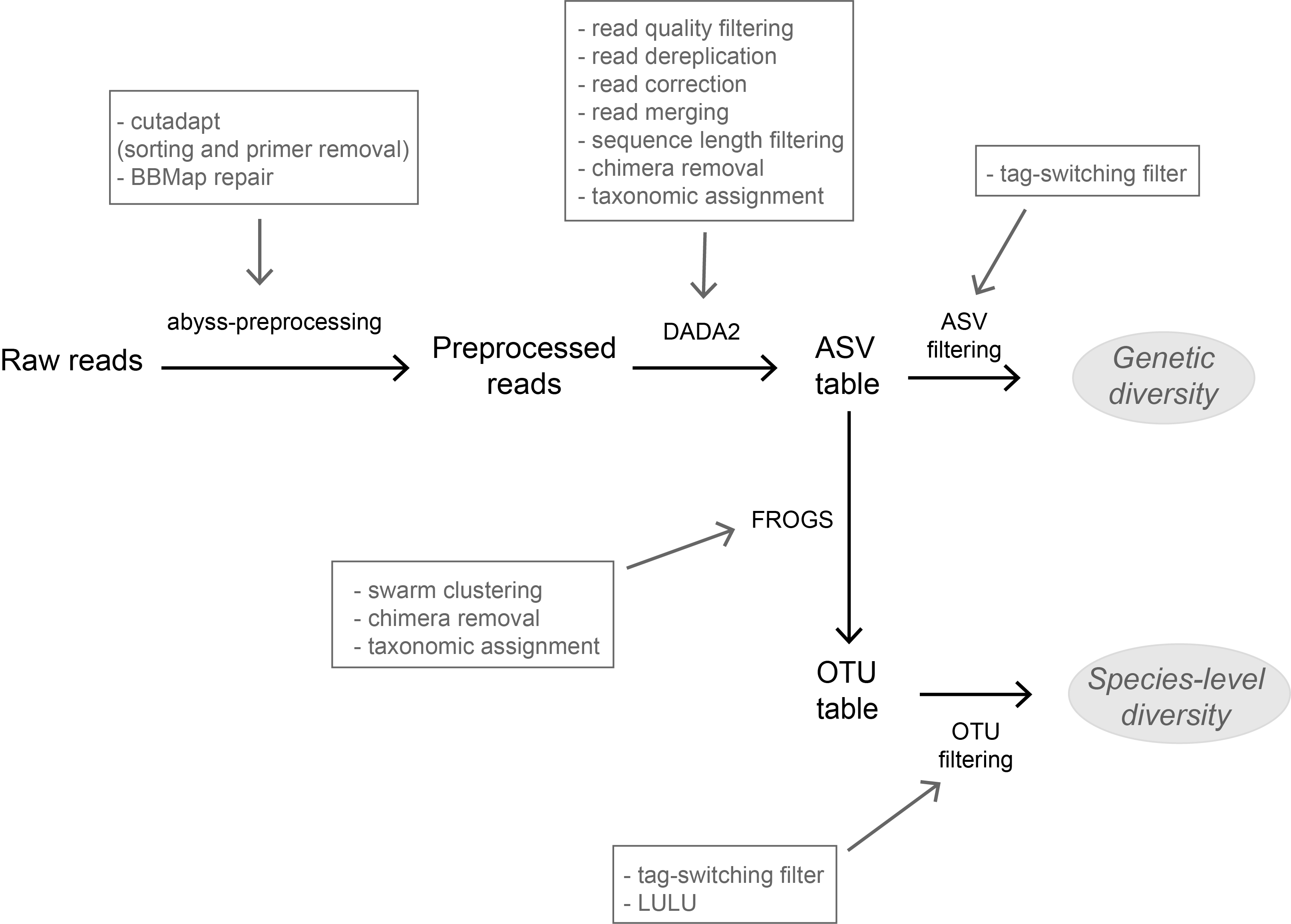

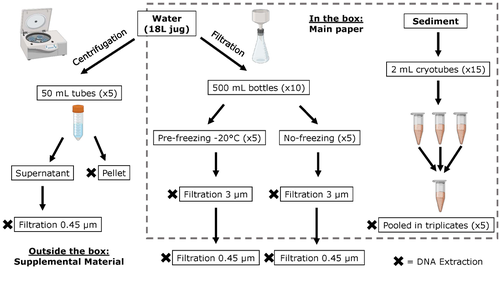

A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingMiriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond https://doi.org/10.1101/717355A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcodingRecommended by Stefaniya Kamenova based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tiago Pereira and 1 anonymous reviewer

High-throughput sequencing-based techniques such as DNA metabarcoding are increasingly advocated as providing numerous benefits over morphology‐based identifications for biodiversity inventories and ecosystem biomonitoring [1]. These benefits are particularly apparent for highly-diversified and/or hardly accessible aquatic and marine environments, where simple water or sediment samples could already produce acceptably accurate biodiversity estimates based on the environmental DNA present in the samples [2,3]. However, sequence-based characterization of biodiversity comes with its own challenges. A major one resides in the capacity to disentangle true biological diversity (be it taxonomic or genetic) from artefactual diversity generated by sequence-errors accumulation during PCR and sequencing processes, or from the amplification of non-target genes (i.e. pseudo-genes). On one hand, the stringent elimination of sequence variants might lead to biodiversity underestimation through the removal of true species, or the clustering of closely-related ones. On the other hand, a more permissive sequence filtering bears the risks of biodiversity inflation. Recent studies have outlined an excellent methodological framework for addressing this issue by proposing bioinformatic tools that allow the amplicon-specific error-correction as alternative or as complement to the more arbitrary approach of clustering into Molecular Taxonomic Units (MOTUs) based on sequence dissimilarity [4,5]. But to date, the relevance of amplicon-specific error-correction tools has been demonstrated only for a limited set of taxonomic groups and gene markers. References [1] Porter, T. M., and Hajibabaei, M. (2018). Scaling up: A guide to high-throughput genomic approaches for biodiversity analysis. Molecular Ecology, 27(2), 313–338. doi: 10.1111/mec.14478 | A flexible pipeline combining clustering and correction tools for prokaryotic and eukaryotic metabarcoding | Miriam I Brandt, Blandine Trouche, Laure Quintric, Patrick Wincker, Julie Poulain, Sophie Arnaud-Haond | <p>Environmental metabarcoding is an increasingly popular tool for studying biodiversity in marine and terrestrial biomes. With sequencing costs decreasing, multiple-marker metabarcoding, spanning several branches of the tree of life, is becoming ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Stefaniya Kamenova | 2019-08-02 20:52:45 | View | |

12 Mar 2023

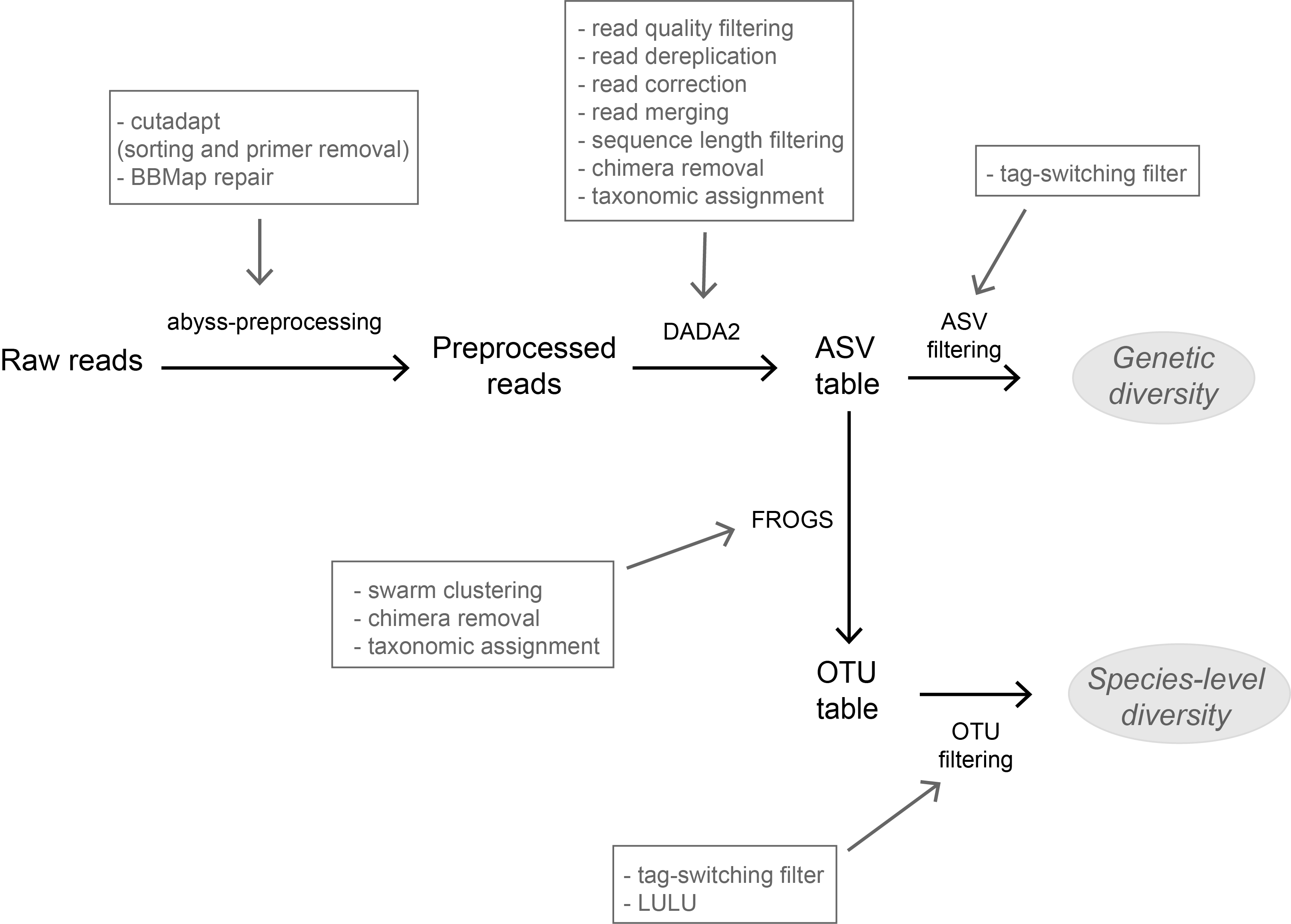

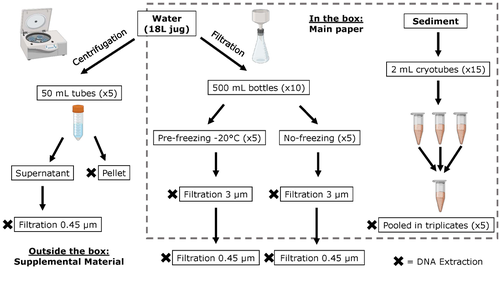

Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities.Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388Processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters from coastal lagoonsRecommended by Claudia Piccini based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Rutger De WitCoastal lagoons are among the most productive natural ecosystems on Earth. These relatively closed basins are important habitats and nursery for endemic and endangered species and are extremely vulnerable to nutrient input from the surrounding catchment; therefore, they are highly susceptible to anthropogenic influence, pollution and invasion (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). In general, coastal lagoons exhibit great spatial and temporal variability in their physicochemical water characteristics due to the sporadic mixing of freshwater with marine influx. One of the alternatives for monitoring communities or target species in aquatic ecosystems is the environmental DNA (eDNA), since overcomes some limitations from traditional methods and enables the investigation of multiple species from a single sample (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). In coastal lagoons, where the water turbidity is highly variable, there is a major challenge for monitoring the eDNA because filtering turbid water to obtain the eDNA is problematic (filters get rapidly clogged, there is organic and inorganic matter accumulation, etc.). The study by Turba et al. (2023) analyzes different ways of dealing with eDNA sampling and processing in turbid waters and sediments of coastal lagoons, and offers guidelines to obtain unbiased results from the subsequent sequencing using 12S (fish) and 16S (Bacteria and Archaea) universal primers. They analyzed the effect on taxa detection of: i) freezing or not prior to filtering; ii) freezing prior to centrifugation to obtain a sample pellet; and iii) using frozen sediment samples as a proxy of what happens in the water. The authors propose these different alternatives (freeze, do not freeze, sediment sampling) because they consider that they are the easiest to carry out. They found that freezing before filtering using a 3 µm pore size filter had no effects on community composition for either primer, and therefore it is a worthwhile approach for comparison of fish, bacteria and archaea in this kind of system. However, significantly different bacterial community composition was found for sediment compared to water samples. Also, in sediment samples the replicates showed to be more heterogeneous, so the authors suggest increasing the number of replicates when using sediment samples. Something that could be a concern with the study is that the rarefaction curves based on sequencing effort for each protocol did not saturate in any case, this being especially evident in sediment samples. The authors were aware of this, used the slopes obtained from each curve as a measure of comparison between samples and considering that the sequencing depth did not meet their expectations, they managed to achieve their goal and to determine which protocol is the most promising for eDNA monitoring in coastal lagoons. Although there are details that could be adjusted in relation to this item, I consider that the approach is promising for this type of turbid system. References Pérez-Ruzafa A, Campillo S, Fernández-Palacios JM, García-Lacunza A, García-Oliva M, Ibañez H, Navarro-Martínez PC, Pérez-Marcos M, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Quispe-Becerra JI, Sala-Mirete A, Sánchez O, Marcos C (2019) Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00026 Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 Turba R, Thai GH, Jacobs DK (2023) Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.495388, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388 | Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. | Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are an important habitat for endemic and threatened species in California that have suffered impacts from urbanization and increased drought. Environmental DNA has been promoted as a way to aid in th... |  | Biodiversity, Community genetics, Conservation biology, Freshwater ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Claudia Piccini | David Murray-Stoker | 2022-06-20 20:31:51 | View |

19 Mar 2024

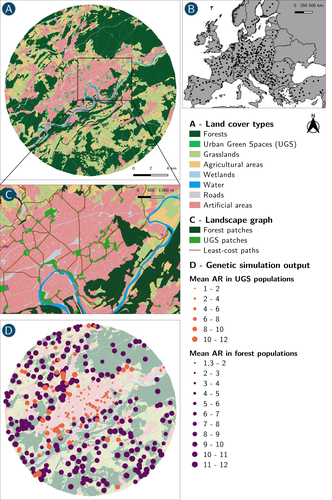

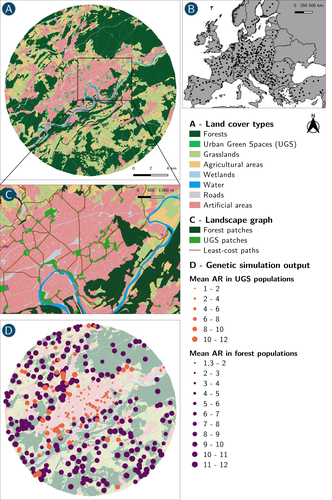

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle